CHAPTER 16

FORWARD CONTRACTS AND FORWARD RATE AGREEMENTS

A business, at times, faces the dilemma of knowing it must borrow money if an event, such as an opportunity to acquire a wanted asset, occurs in the near future. The business knows the approximate amount needed for the acquisition, but the borrowing cost of the money needed to pay for the asset may dampen its appeal or even negate it. If the business had some way of knowing what its borrowing cost (interest rate cost primarily) would be, it could more accurately assess the cost of the opportunity. The derivatives market offers two products that give some control of borrowing cost to business management. One product is similar to a future product; the other is similar to a call option. The one that is similar to a future product is known as a forward contract. Unlike a future, all terms of the forward contract are negotiated, and there isn’t a secondary market for trading in or out of position. The other product is a forward rate agreement, which locks in a negotiated interest rate for a period of time. By that predetermined time, the owner of the FRA activates the contract or lets it expire.

• FORWARD CONTRACTS •

As future products trade on exchanges, forwards trade over-the-counter. The terms of a future product are set by the exchange on which it trades. The quantity, quality, and delivery requirements are stated in the specifications. The specification for the contract is the same for all contracts in that product with a deliverable in that month. In other words, the contracts are standardized. In the case of forwards, each contract is negotiated. With both products, there are advantages and disadvantages to this method of trading. In the case of the future, the contract is predescribed by the exchange on which it trades. Therefore an April contract on a particular oil product is the same as any other April contract on that same oil product. In the case of a forward contract, all terms are negotiated; therefore you have different quantity quality and different delivery periods. Because of the standardization of contracts on the future exchanges, there is liquidity and a secondary market.

As stated above, the contracts are the same no matter what differences there are in the products on delivery. These differences are addressed when the products are actually delivered. The future contract on coffee, for example, has seven different grades. What is traded while the coffee is in the future state is grade 4. The adjustments are then made later through the clearing corporation at the time of delivery. If a forward agreement was enacted to trade coffee, the participants would identify the exact grade and type of coffee that is going to be delivered; thus forward contracts lend themselves to one-off negotiated agreements. Forwards do not clear and settle through a clearing corporation, so each transaction must be settled one by one without the benefit of netting. Unless provided for in the agreement, mark to markets are not usually performed. Pricing of a forward is the same process as used for a future contract: the current commodity price, plus the cost of carry, insurance, storage, etc. As there isn’t a clearing corporation involved, there may be an additional charge for credit risk.

The British pound future contract traded in the United States is 62,500 British pounds denominated in dollars. What would happen to a client who only needed 25,000 British pounds? She could not go into the future market to secure this sum, so she would have to turn to the forward currency market, where there are dealers willing to trade 25,000 British pound contracts. The terms of the contract would be negotiated as far as the conversion rate, the delivery date, and the delivery location.

The major products that trade in the forward market are currencies, interest rates, and precious metals. The currency forward is especially important, as many of the nonmajor currencies that trade on the future market are needed for business dealings around the world. Let’s take a look at forward trade: the U.S. dollar versus the British pound. It would be written GBP/USD, meaning we are using U.S. dollars to buy the British pound. Assume the British pound would cost $1.50 per. The converse of that would be that you would need 66.7 pence to buy one U.S. dollar.

Now let’s set up a hypothetical case: The company Crumpets Importers is a U.S. business. It is going to buy 100,000 British pounds’ worth of crumpets for sale in America. At the current exchange rate this would cost $150,000. The company is hoping to sell the crumpets and make a 10 percent markup on the transactions. Therefore, to accomplish this feat, it must sell its crumpets for $165,000. The crumpets will be delivered six months from the day of the transaction. Crumpets Importers has a choice: it can buy the British pounds now, it could hold off and buy the British pounds six months from now, or it could buy a forward contract on the British pound at $1.50 a pound. Each of these alternatives has its positives and negatives. If it buys the British pounds it needs now, it is without the use of $150,000 for the next six months; therefore the company may have to borrow money should it run into some processing problem or some other need.

The $150,000 that the company surrogated is very dear funds. If it waits until the crumpets are delivered, it’s exposed to market risk because no one knows exactly what the conversion rate will be six months from now. The safest and surest approach to this problem would be if Crumpets Importers went into the forward market and bought a contract that would lock in a price of $1.50 per pound to be delivered six months from now. This contract would cost a fee of course, but that fee is factored into the overall cost of the project. Let’s assume a forward cost of 2 percent a year or 1 percent for the six months. So on the 100,000 British pound contract, it’s going to cost Crumpets Importers 1,000 British pounds or $1,500. For that fee of $1,500 it has locked in the rate of $1.50 per British pound.

Let’s assume that over the six-month period of time, the dollar weakened against the British pound, so that six months from today, it will cost $1.60 to buy one British pound (or in this case $160,000 to buy 100,000 British pounds). Assuming that Crumpets Importers has no latitude as far as the selling price goes, its profit of $15,000 has now been reduced to $5,000 since it would have to go into the market if it did not have the contract and pay $1.60 a pound or $160,000 for 100,000 pounds.

Of course the dollar could have strengthened over the six months, so now let’s assume it was $1.40 to buy the 100,000 pounds; it would cost the company $140,000 to convert to 100,000 British pounds to pay the company in England. If it could still retail the product at the assumed $165,000 it would have increased its profit margin from 10 percent to almost 18 percent. However, if it had purchased the forward contract and assumed that it could still sell the product for $165,000, it would only make the 10 percent less the cost of the contract.

• FORWARD RATE AGREEMENTS (FRAS) •

A forward rate agreement (FRA) is an agreement that sets either an interest rate or an exchange rate to be effective sometime in the future. It is an integral part of money markets and is basically a kind of delayed loan. An interest rate FRA is a delayed interest payment on a notional amount set by the two parties. Let’s suppose that a business wants to lock in a rate commencing two months from the time the contract is signed and terminating eight months after the contract is signed. In other words, the duration of the contract would be six months. That would be designated “2x8,” which translates to a contract that becomes effective two months from the signing of the agreement and terminates eight months from the signing of the agreement, the difference being the six months that the business is looking to protect. This product is basically a short-term derivative with a single payment at the end, depending on the interest rates that are involved or the difference between the reference rate, which is decided, and the actual rate that is in place when the period of time involved occurs.

The FRA has two parties involved in the contract: the buyer, who is protecting against interest rates rising, and the seller, who is protecting against interest rates falling. What is involved, as mentioned above, is the notional amount and the time period during which the FRA will exist. The interest rate that is applied is based on the notional amount. What is settled between the buyer and the seller is the difference between the reference rate and the effective rate that is in force at that time.

If interest rates should rise, then the seller will pay the buyer the difference between the reference rate and the contract rate because it is costing the buyer more money to borrow money. If, on the other hand, interest rates should fall, the buyer would pay the seller the difference to make up for that shortfall in interest income. Let’s suppose a reference rate of 5 percent is set at the time of the contract signing. On the date the FRA takes effect, the borrower/buyer has to borrow money at 5.5 percent. After the agreed-upon period of time has elapsed, the seller would pay the buyer the difference between the 5.5 percent rate the borrower paid and what the reference rate called for. Therefore, the effect of this compensation would be to adjust the borrow rate to the contracted rate. If on the other hand the interest rates were to fall to 4.75 percent, which is below the reference rate of 5 percent, the buyer would pay the seller the difference so that the effective rate is the contract rate. Therefore the seller would receive the same benefit as if the rate itself had remained at 5 percent.

Since the reference rate and the actual rate are both known at the beginning of the FRA, the difference between the two is settled at the effective date. The formula for computing the amount of money owed to the individual who is benefiting from the FRA is as follows:

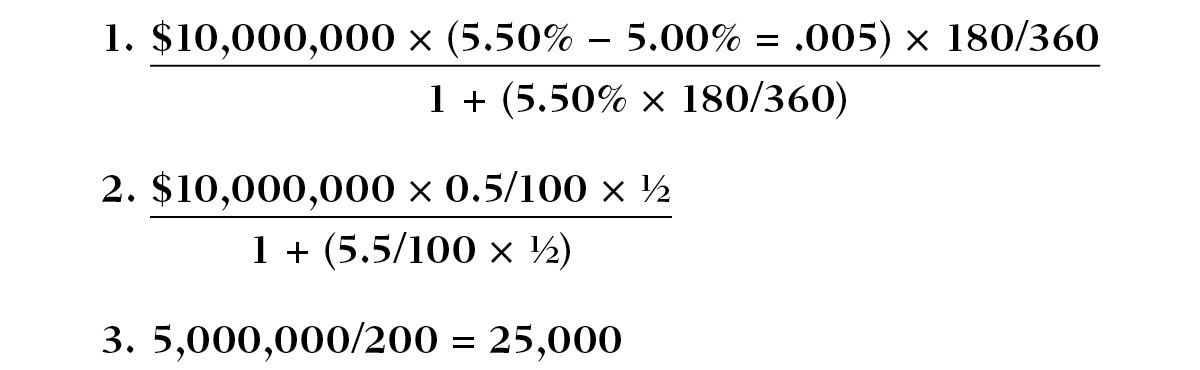

notional amount × (reference interest rate − FRA rate) × number of days / base number of annual days [360 or 365] divided by 1 + (reference rate × number of days / base number of annual days)

Here’s how that concept would look as a numerical example:

Loster Motors negotiated $10 million of a 2x8 FRA (180 days) at 5% rate. Referenced rate is 5.50%. Using a 360 basis the formula would be:

In the next chapter, we will be taking a look at swaps.