CHAPTER 21

COLLATERALIZED DEBT OBLIGATIONS

Investors in long-term debt sometimes prefer to have their risk spread over several different long-term instruments rather than dedicated to one. For example: A bank will lend a client $100,000 to buy a home. The home is used to collateralize the loan, which becomes a mortgage. The bank then sells the mortgage to an investor. The investor is one on one with the homeowner. Whatever actions the homeowner takes that affect the home could affect the mortgage, which in turn affects the investor. In other words, all of the risk the investor has is tied up in this one mortgage. To diversify the risk, the investor would have been better off investing the $100,000 in a pool containing ten or twenty mortgages. This risk sharing is what is behind all of the following collateral debt obligation products. Investors are more willing to spread their risk than they are willing to put all their eggs in one basket.

“Collateralized debt obligation” (CDO) is a term that applies to several different securitized products, including a derivative, that spread the risk. First let us look at the variety of securitized products.

• THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF CDOS •

Under the umbrella of collateralized debt obligations are the following products: collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), collateralized bond obligations (CBOs), and collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). The purpose of the securitization of these loans is to spread the risk of default among several debt contracts of the same type. There can be one hundred debt contracts in an individual CDO. Once securitized, the CDO is disbursed to investors, thereby permitting investors to spread the risk of default over a multitude of debts of a certain variety. In addition, there are synthetic CDOs in which the underlying asset is not actually owned. Instead, the issuing firm has amassed credit exposure by selling credit default swaps and using the proceeds to buy low-risk debt.

Collateralized Mortgage Obligations (CMOs)

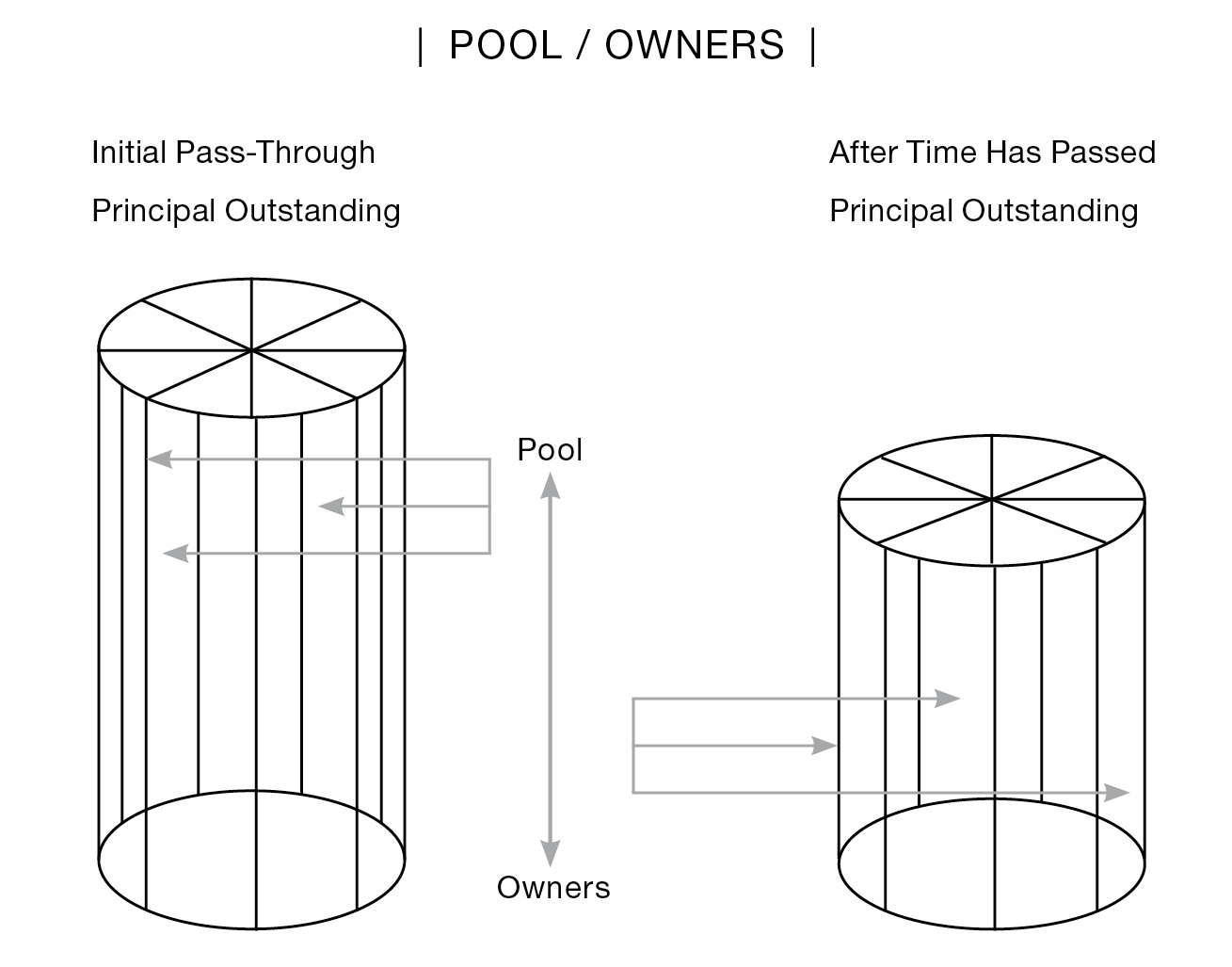

Let’s go back to the beginning of this segment of the industry. Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA, or Ginnie Mae), a division of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), issued the first collateralized mortgage debt in 1970. GNMA contained a pool of government-insured or -guaranteed home mortgages. These mortgages were backed by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the Office of Public and Indian Housing (PIH), and the Department of Agriculture’s Rural Housing Service (RHS). GNMA guarantees the timely payment of principal and interest due on the pools to the GNMA holders. It was structured as a “pass-through” instrument that tracked the mortgage payments made by those homeowners whose mortgages were part of the pool. As the homeowners made their monthly payments (comprising principal pay-downs and interest payments on the mortgages’ outstanding principal), the payments were passed through to the GNMA pool owners in proportion to the amount of the pool they owned. Generally speaking, GNMA receives 6 basis points and the mortgage servicer retains 44 basis points, which means that GNMA mortgages of 5 percent will pay the GNMA pool holder 4½ percent. The owners received monthly payments of principal and interest. As mortgages do not mature, their principal depletes to zero.

Owners

These monthly payments were affected by mortgages that either refinanced homes, sold homes, or took some other action that negated the original mortgages. Mortgages could be paid off and ceased to exist and the proceeds passed through to the GNMA pool owner. New qualified mortgages are added to new pools, not existing ones. As a result, the GNMA owner will receive scheduled principal pay-downs and prepayments when they occur.

Issuance

GNMA’s modified pass-throughs are issued through the efforts of a mortgage banker. While not a true banker, a mortgage banker has as its primary function arranging financing for buyers of new homes. The mortgage banker must also sell the approved mortgages and enforce them to buyers. Some of these mortgages will qualify for coverage under GNMA as stated previously. Those that qualify will be sold as GNMA pooled mortgages. Those that do not qualify will be sold as conventional mortgages, either as whole loans or pooled as collateralized mortgage obligations (CMO) as part of the asset-backed securities (ABS) universe.

There is a period of time between when homeowners get their mortgages approved and when they move into their new homes and the mortgages go live or are enforced. During that period of time the mortgage banker, or the financing agent, is at risk for changes that may occur in mortgage market interest rates. As it is not a primary function of mortgage bankers to take on any interest rate risk that they do not have to in the course of their business, they will go into the GNMA market and offer the approved but not enforced pool of mortgages to GNMA dealers. The span of time until the pool is alive could be several months. At this point the amount of mortgage principal, the rate of interest the pool will carry, the “maturity” date of the mortgages, and the delivery day of the actual pool are known. What is not known is the unique number that GNMA will assign to this pool. That unassigned unnumbered pool is known as a TBA (to be announced).

TBA

The GNMA dealer will offer the TBAs for trading in the over-the-counter market. They are sold into the market and during this period of time will not pay any interest or principal, as the mortgages representing the pool are not enforced and the homeowners are not yet paying them down. So the TBAs are traded as purely as an interest rate value.

In the marketplace there are many TBAs being offered and traded. All those that have in their nomenclature the same product, interest rate, delivery date, and debt maturity date will trade as one instrument. Members of the Mortgage-Backed Security Division (MBSD) of the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC) of Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC) will assign an ID number to each TBA being traded. Therefore, as with many derivatives, it is possible for there to be more TBAs of one class being traded than are actually going to be delivered.

Participants in the market sell and buy or buy and sell TBAs. Depending on the financial strength or nature of the firm’s client, some clients must post margin against their positions while others may not. As the TBA period nears its end, participants “unwind” their positions, leaving only those who want to be recipients or deliverers of the actual pool. As mortgage rates fluctuate from day to day the participants’ maintaining positions will see the value of holdings increase or decrease. It is important to note that as the actual pool has not been issued, there isn’t any real product outstanding. Therefore, the buyers of the product cannot really buy anything and the sellers cannot deliver anything. This permits them to go in and out of TBA positions at almost no cost. The resulting profit or loss from this trading activity is real and will be settled at the appropriate time.

Mortgage Backed Security Clearing Corporation (MBSD) keeps a daily tally of the trading and activity of its members from the time the TBA starts to trade until settlement. At the end of the TBA period, it will issue receive and deliver instructions to its participating members. The obligation to receive or deliver will be based on the unilateral net balance of their activity. All clearing members of the corporation will be processed through the same unilateral netting process. As a result, the contra side to the settlement instruction may be a clearing member that the member did not trade with, but ended up on the other side for the settlement. It’s worth noting that MBSD will act as a central counterparty (CCP) to all trades. Therefore, in this process, all TBA buy trades will be submitted against MBSD and all TBA sell trades will be submitted against MBSD. At the end of the trading period MBSD will issue settlement balance orders to the netted members. Market participants that are not members of MBSD will settle their transactions directly with their contra parties on a trade-for-trade basis or may choose to use a bilateral netting service against contra firms.

Clients who conduct TBA transactions through these member firms will net out at the end of the TBA period. Those clients that have positions will make arrangements for settlement. Most of these arrangements will enlist the services of a clearing bank.

The GNMA Market

An industry suddenly grew out of this product. At issuance, all mortgages in the pools are assumed to mature within a few months of one another. Once they are issued, however, the demographics of the mortgage owners set the tone. For example, mortgages issued to homeowners in a geographic area appealing to retired homeowners would have a much longer life expectancy than mortgages given to homeowners who reside in a transient area, such as a high-tech region where homeowners change jobs frequently. Therefore, GNMA pooled mortgages were priced at their weighted average maturity (WAM), which was developed from experiences gained from previous pools and observations.

Even though the mortgages were all issued with the same or similar “maturity,” the passage of time and the actions of the homeowners and the changes in interest rates would cause the average life of the pool to change—and through that change, the market price of individual pools would also change. In addition, the mortgages are debt instruments and interest rate sensitive. Therefore, as mortgage interest rates fell, homeowners would refinance their homes, retiring their higher-rate mortgages with the proceeds from their new lower-rate mortgages. To the GNMA pool owner, it was as if there were an unwritten, hidden call feature. Their pool of twenty-five-year mortgages was suddenly partially retired in X years as Y number of homeowners refinanced.

Other factors would also affect the life of a mortgage. Relocation of the homeowner and the need to capture the built-up equity for expenses such as children’s education are just two reasons for early termination. In recent years, we witnessed a new situation: homeowners’ walking away from their responsibilities as the value of the property fell below the mortgage balance, or because of economic hardship. During the life of the mortgages, the payments of interest or principal were overseen by a mortgage servicer.

The GNMA market continues to grow and GNMA-IIs were introduced, which allowed for single-rate mortgages as in GNMA-I, or mortgages with different interest rates in the same pool. With these multirate pools, the division of the rates affected the pricing. This change gave way to WAC (weighted average coupon) pricing.

REMIC

Investors were looking for a way to better control their cash flow. Some wanted a shorter loan period; many wanted more flexibility than was afforded them with the pass-through format. In 1983, Freddie Mac (Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation) issued its first collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO). Since then Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) have been issuing CMOs. In order to clarify possible confusion, a change in the tax law in 1986 introduced real estate mortgage investment conduits (REMICs), which are legal entities that issue CMOs. REMICs allow CMOs to be issued with a minimum of tax complications.

Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae were created by Congress and established as government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs). The CMOs are backed by the agency. While Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac do not make direct loans, they assist lenders by providing funds. They acquire mortgages from lenders, package them, and sell the securitized products into the market.

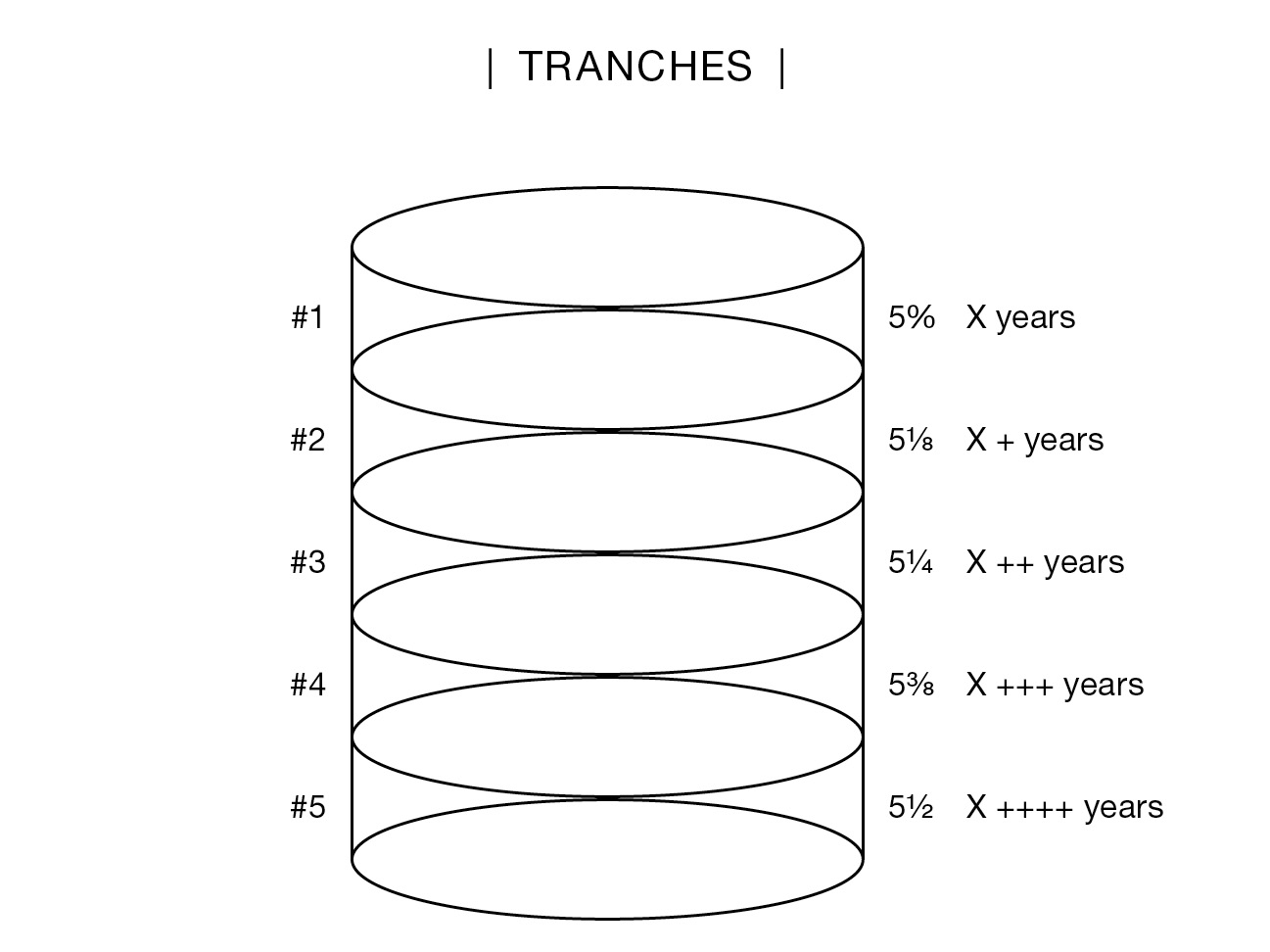

Tranches

Let’s take a look at how a CMO works with the tranches below, and how they “mature” sequentially.

Each tranche pays a stipulated rate of interest based on the time to maturity. Principal received from the mortgagees is applied against the first tranche. When it is paid down, the principal flows to the second tranche and so on. As with pass-throughs, the prepayment of mortgages hastens the retirement of the pool. Using the above example, let’s assume tranche #5 is supposed to be receiving principal payments from years 21 to 25. The owner of the tranche would be receiving that rate of interest on the outstanding principal from day one. Now let’s suppose that the tranches were paying down faster so that by year 16 the first four tranches were paid down. Then from year 16 on, the owner of tranche #5 is receiving interest on a 16+ year instrument at a rate of a 21+ year instrument.

The CMO trades of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae are cleared through MBSCC.

Non-Government–Backed Collateralized Mortgage Obligations

Private mortgage companies, like banks, issue CMOs also, but these do not have any government guarantees. Therefore, the structure of their CMOs is different from those that are government issued. As is the case with those of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, the CMOs are divided into tranches. These tranches cover different parts of the CMO. They could be divided into classes, such as A class, B class, C class, etc. All the tranches of the particular CMO collectively make up the CMO’s capital structure. A rating agency such as Moody’s rates the tranches.

The CMO prospectus details the hierarchy of the tranches. They are listed from AAA, the most senior, down to unrated, the most junior. The tranches below the senior tranches but above the equity tranche are known as “mezzanine tranches.” The most junior tranche is known as the “equity tranche” because, if all goes right, it stands to earn the most as it has the highest coupon. Naturally, the AAA rated are the safest but have the lowest “coupon rate” of the tranches. Cash flowing in from the underlying debt is directed to the AAA tranche first and then down to the riskiest of all, the equity tranche. The equity tranche is also referred to as the “toxic waste” tranche because if anything goes wrong, this tranche gets hit with it first, including any defaults, short payments, drops in market value, etc. In the case of losses, the equity tranche absorbs them first, then the tranches up the line absorb them in order of seniority, with the senior tranche absorbing them last.

Z Tranche

Some CMOs have a “Z” tranche, which acts like a zero-coupon bond not receiving any interest or principal until all other tranches have been paid down. It is an interest tranche because, being the lowest on the totem pole, it absorbs any defaults first. However, the interest that it is supposed to receive accrues in its principal, so that in a perfect world, at the end of the CMO or CDO, the Z-tranche owner receives the principal plus the accrued interest, which can now start to earn interest itself.

Collateralized Bond Obligations (CBOs)

Collateralized bond obligations are pools of corporate bonds of varying degrees of risk, including junk bonds that are securitized and sold to the public. Due to the diversity of risk that these bonds represent, they offer an opportunity to receive a higher rate of interest without concern that the entire issue may fail at one time. That fear is evident in the acquisition of a single junk bond. In other words, the risk of default is spread over many bonds. The CBO is issued in tranche format. The idea is to take the possibility of default from one product, with the bond owner(s) absorbing the whole loss, to many diversified junk bond products and many shareholders, where the loss of a bond due to default is shared among many.

Collateralized bond obligations are rated as investment grade based on the possibility that all the bonds won’t default at the same time. Therefore there is safety in numbers. As the primary content of the CBO is junk bonds, the bonds must be yielding a high rate of return, which is passed on to the investor. If, when the bonds were originally issued, they were considered non-investment-grade or junk, then they issued with a high “coupon” rate compared with other less risky bonds. If, on the other hand, the bonds were investment grade when issued, but the issuer’s finances have weakened and are now at a point where they are considered below investment grade or junk, then the bonds’ market price would have fallen in value to the point that they were yielding a high rate—one that is equivalent to the coupon rate of a junk bond. An investor obtaining a position in CBOs who can close it out before a default occurs would have done exceptionally well with the investment. If there were defaults during the holding period, the size of the default compared with the whole would determine the outcome of the investment.

It may still be a better option than one bond, one investment, one default. The tranches are rated by a rating service, with senior, mezzanine, and equity tranches.

Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs)

Major corporations in good financial condition usually find it easy to borrow money. Even those whose financial condition isn’t stellar can generally negotiate good terms. Midsize and larger businesses may find good borrowing rates harder to come by because of the nature of their business, their location, competition from bigger or foreign companies, or just the economic climate in general. Financial institutions will take these loans and pool them together and sell them as a unit, in a manner following the tranche format with senior, mezzanine, and equity tranches.

The concept of a collateralized loan obligation is to spread the default over many participants, thereby lowering the risk per individual. As with other tranche-issued debt, the tranches descend from senior to equity tranches as the risk of default grows. As the risk of default rises, so does the interest rate paid on the respective tranche.

CLOs are made up of car loans, credit card loans, boat loans, and other commercial loans. One of the major users of this market is Sallie Mae (SLM Corporation, originally the Student Loan Marketing Association). The product is developed by banks and other lending institutions as a way of recouping funds so that they can continue their business of making loans. The loans are not guaranteed by the developers. Therefore, a bank would gather loans of a certain type that it has made and package them. The package is sold to a third party, who securitizes them and sells them into the market. That third party is known as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) or special purpose entity (SPE). The buyer of the securitized product may be a special investment vehicle (SIV) that sells shares of the CLO to its clients or may sell the shares in the over-the-counter marketplace.

• COVERED BONDS •

Covered bonds originated in Europe centuries ago. Only recently did they begin to appear in the United States. They were brought to the forefront by former secretary of the treasury Henry Paulson. These instruments offered a more secure method for investors and distributors to enter a liquid debt market. The introduction of the product occurred during the credit crises and has the structure to avoid many of the pitfalls of collateralized debt obligations.

What separates covered bonds from other debt derivatives is the recourse that investors have in case of default. Unlike the typical collateral debt obligation, where the investor can lose his or her entire investment should the pool of debt instruments go into default, the investor has recourse against the issuer or the organization the issuer is affiliated with, as well as the covered pool itself.

The assets that make up the pool are segregated from the issuer’s other assets. The issuer cannot use these assets for any purpose other than to support the covered bonds. Because the assets are locked in, investors can examine the quality of the assets to determine value and risk.

Another difference between covered bonds and CDOs is that covered bonds remain on the issuer’s or distributor’s books and are not sold off to another entity, as is the case with CDOs. The lender issuer of CDOs sells the pools to a special purpose vehicle, which in turn issues shares against the pool. Therefore any malady that befalls the pools also affects the issuing party.

In addition to Europe and the United States, New Zealand and Australia are in the midst of offering these instruments. The product trades in an over-the-counter environment with several institutions creating it. Transactions are settled between parties through correspondent banks.