CHAPTER 24

DERIVATIVE TRANSACTION PROCESSING AND THE DODD-FRANK ACT

Passed in 2010, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act addressed three main serious problems. First, the amount of capital required to support derivative positions maintained by financial institutions was deemed to be insufficient. Second, the amount of trading risk being taken by institutions whose primary purpose was clients’ financial services was growing. Third, there was a lack of transparency (disintermediation of a third party) in the market because there wasn’t any reporting of price and other transaction information through a central facility.

Thus one of the major parts of the Dodd-Frank Act focused on product processing and transparency, via an entity called a swap execution facility (SEF). The European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR) and Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) are both addressing the same issues. The main concern is both the number of trades and the billions of dollars’ (and other currencies) worth of derivatives and structured products that are not in a “controlled harbor” but floating around somewhere in the “clouds” (either systemically or archaically). Section VII of the Dodd-Frank Act requires that certain over-the-counter derivatives (the Act’s term is “swaps”) be cleared through exchanges or clearinghouses. Currently some exchanges offer systems that operate from product trading through to settlement, as in some futures markets. In other markets, the exchanges and clearing facilities are separate entities.

For example, the Chicago Board Option Exchange (CBOE), where option products are traded, and the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC), where all CBOE-traded options settle (as do the option trades from exchanges), are two separate entities. Dodd-Frank further clarifies the responsibilities of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), with the SEC having the authority over “security swaps” and the CFTC having authority over all other swaps. As of the writing of this book, the trading, clearance, and settlement of some derivative products are highly automated, while others are at the opposite end of the spectrum.

• CUSTOMIZED VS. NONCUSTOMIZED PRODUCTS •

The term “customized” takes on a completely different meaning when it comes to processing. Transaction processing involves the structure of the product and not what it is composed of. Listed issues, those that trade on exchanges, follow a regimented format. A trading lot of ZAP common stock, structure-wise, is the same as a trading lot of RAM common stock, and so on. Certain over-the-counter products, by their very nature, also follow the same format as other similar products. GNMA pass-through securities are an example of this. While the number of pools that make up the trading unit, as well as the coupon rate and mortgage expiration date, may all be different, the product conforms to a set of processing requirements. This structure requirement makes processing of transactions more efficient through the use of electronic processing and through the employment of clearing corporations. In the case of GNMA pass-through securities, the clearing corporation Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBSCC) is one of the divisions of the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation (DTCC). Some over-the-counter products are not automated because the volume of transactions is so low it’s not warranted.

Noncustomized Transactions

Not all derivatives are customized. Many are standardized in structure. For instance, futures, listed options, options on futures, and mortgage-backed securities issued by GNMA, Freddie Mac, or Fannie Mae are all customized products but standardized in structure. Credit-linked notes are an example of where the structure is missing, as the component parts, individually, require their own processing and are not the same from one note to another.

Customized Transactions

In terms of operations, a customized product is synonymous with a one-off transaction: a trade so different from the rest that it must be manually processed or one that, as a group, has such little volume that the cost of developing, running, and servicing a system is not cost effective. The customization of a transaction can involve a product or a transaction. A product would be a call option on 150 shares of ZAP preferred stock with a strike price of $53.35 expiring at 12:00 noon on May 24. The structure is that of an option, its nomenclature is a one of a kind. A customized transaction would be a structured product where an ETF on TAN index of the top fifty European stocks is acquired and two of the stocks that are in the ETF are shorted and five other stocks, not in the ETF, are acquired in quantities other than their trading lots. This type of trade requires special handling and processing and its purpose is known only to the principal.

• EVOLUTION OF DERIVATIVE PROCESSING •

The first item that must be addressed is the misconception that the processing of nonderivative products is all “straight-through processing” and that derivative products are processed by chisel and stone. To understand the concepts and steps along the way, we will follow the listed option market from before the Chicago Board Option Exchange (CBOE), the first “listed” option exchange, was launched, and the effects it had on the option world. In many ways some of our derivatives products of today run the same way the option market did back then.

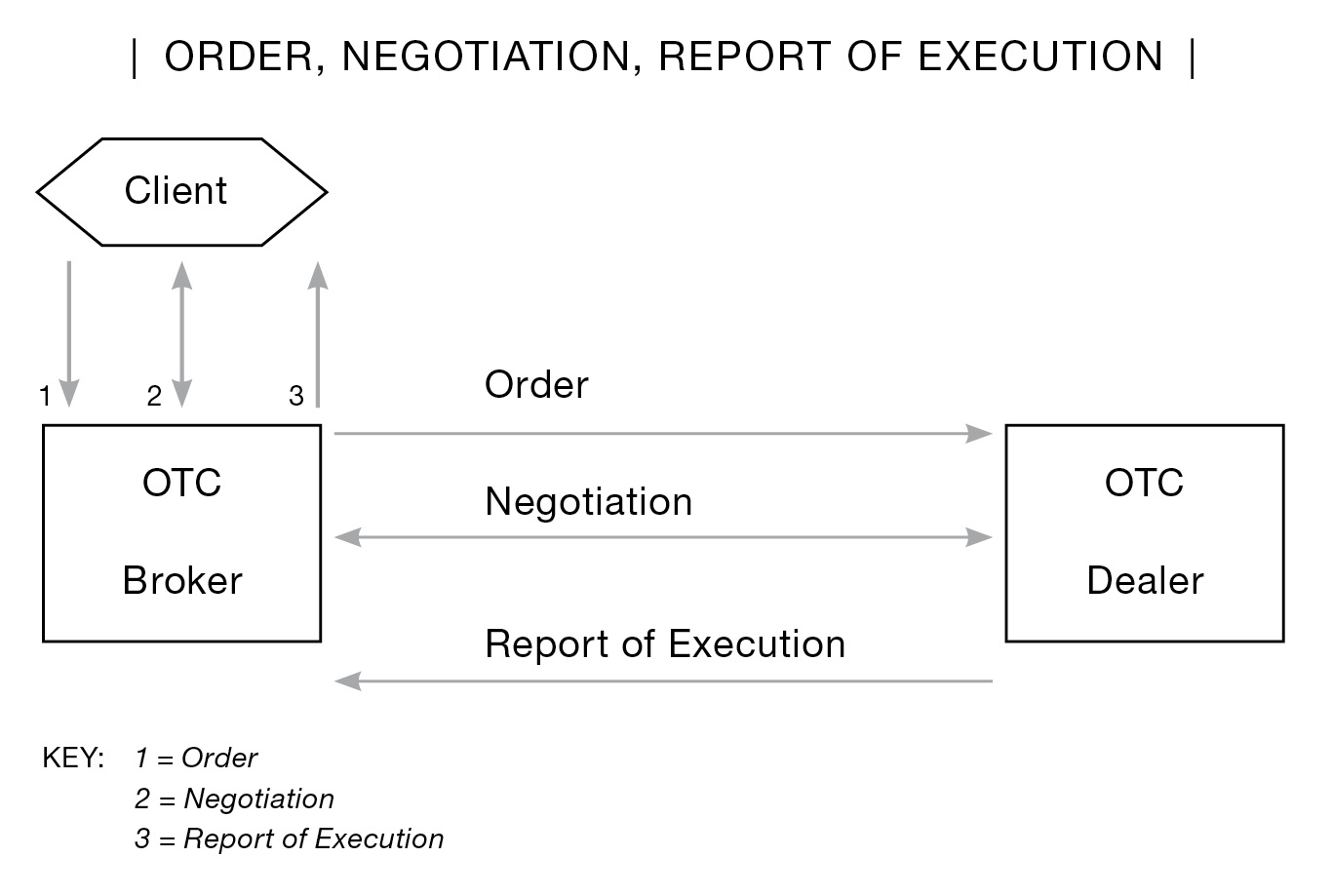

Prior to 1973, almost all put and call options were on common stock and were traded in an over-the-counter environment. The marketplace was small. SEC-registered broker-dealers known as put and call dealers made markets, published prices on a half dozen of their “offerings” in the newspaper to attract interest, and investors would call their broker-dealers, who in turn would call the put and call dealers and negotiate the terms of the new contract. Once this was agreed upon between client, broker-dealer, and put and call dealer, the broker-dealer would trade against whichever dealer gave the best terms and price. The broker-dealer then wrote up the terms and price on an order ticket. The ticket was used as a source to print out the customer’s trade confirmation, which was mailed to the client with a copy going to the broker-dealer’s operation department to be matched to the actual put or call option contract when it arrived from the put and call dealer.

At the same time the put and call dealers would type the terms of the option contract and physically deliver the option paper contract to the client’s broker-dealer, who in turn would match the terms against the customer’s confirmation and hold the contract pending later instruction. This is the genesis of the current terms “holder,” the one who can exercise the option, and “writer,” the one who can be assigned to perform the terms of the contract. There wasn’t any record maintained by the put and call dealer as to who actually retained the paper contracts; rather, the put and call dealers knew their positions but didn’t know who actually held them. If a “holder” should lose the paper contract, there wasn’t any replacement to be had because the document was in bearer form, so whoever should surrender the option paper to the put and call dealer was assumed to be the owner. Therefore, anyone turning in the paper contract to the put and call dealer could exercise it.

Trading between the investors did not exist, as there wasn’t a secondary market. All trades were against the put and call dealers. Broker-dealers would exercise options on behalf of a client or for their own proprietary account, surrendering the option paper to the put and call dealer. Both firms would then submit trade report tickets to their operation departments and the trades would be manually processed by the two firms. This should sound familiar, because some of the derivative trades we process today look very similar.

The Opening of the Chicago Board Options Exchange

On April 26, 1973, the CBOE opened its doors and the options world changed forever. The listed options market accomplished the following:

- Standardization of the product was accomplished when option format structure was established. The core or structure of all listed options is the same; details of the individual trades are different. The option must be a put or call, it must be a buy or sell, and it must be for a trading lot, etc.

- New options products that are to be listed for trading must be approved for trading by the Securities and Exchange Commission and by the Options Clearing Corporation (OCC). Additional option series that may be required due to price movement of the underlying product are added by OCC as provided for by rules for put and call options, with the same series designation added at the same time.

As a result of the standardization and the orderly way options are issued, a secondary market developed with participation from brokerage firms (and their customers) trading against other member brokerage firms and against member floor traders (market makers who added liquidity to the market). Therefore brokerage firms executed their customer orders against other brokers and market makers on the trading floor of the CBOE. Brokerage firms executed “upstairs” proprietary orders against other brokers and traders as well. Traders, operating on the exchange floor and from “upstairs” trading rooms in their respective firms, added liquidity to the market.

Execution price transparency was accomplished when trade prices were captured by an independent third party known as the Options Price Reporting Authority (OPRA). These prices were made readily available to the public. Historical pricing records were available to auditors, regulatory personnel, and the public. It is this pricing element that is missing from some derivative products and addressed in the Dodd-Frank Act.

Option products and members were assigned to areas of the floor to balance trading volume and product servicing. Today, physical floor locations are no longer needed, as technology has improved and the use of electronic markets has been replacing the need of a physical trading floor.

Another area addressed by the Dodd-Frank Act was the lack of any execution detail for certain derivative transactions being captured by an independent third party. In the case of listed options, execution details are reported to the source of the order and to the OCC. It is the OCC that is responsible for reporting trade comparison and verification between submitting brokerage firms. The matching and comparison are now performed systemically, with trades where the buying and selling firm do not agree as to details (known as “uncompared trades”) identified and highlighted, leaving no doubt as to the validity of each trade. Firms’ management, internal and external auditors, as well as regulators can review current position risk, problem transactions, and exposure to potential loss.

As options involve a “second life”—the period between the opening or establishing of a position and option expiration or closing of the position—a record is maintained of outstanding option positions by the OCC, and the respective broker-dealers maintain the positions in customer, firm (proprietary), and market maker control accounts. In addition, firms must adhere to SEC rules forbidding commingling of aforementioned positions. This record keeping by an independent third party, in this case OCC, is another requirement of the Dodd-Frank Act.

Margin requirements were established based on the perceived risk of the overall positions maintained by the firm. The amount of margin required was deposited with OCC, which operates as a central clearing party (CCP) to all compared trades. Trade settlement involves unilateral netting—all compared transactions will net out to zero! For each buy transaction there must be a sell transaction. The two parties must agree as to trade and settlement date, type, class, series, and price. Therefore this allowed unilateral netting for both product and cash, and cash netting is financial entity bound, not product bound.

In summation, this is what the Dodd-Frank Act requires for actively traded derivatives. The concerns that led to the act’s passage are especially urgent, as many of these trades are global in nature and not under one regulatory authority.

• A NONSYSTEMATIZED EXAMPLE •

Party A (an investment bank) receives a phone call from a client who discusses a transaction he would want to do if the terms are amenable. The client has an established account at Party A so that part of the process is in place. Party A contacts Party B (another financial institution and possible contra party to the transaction) and discusses the requested transaction. Party A is representing the client. Assuming it is a swap, Party A is a swap broker, and Party B is a swap dealer. If Party A does not have a master agreement with Party B, the terms and conditions contained in the master agreement must be agreed to, approved, and signed by the appropriate personnel of both firms.

Next, the two parties, A and B, negotiate and review the terms of the transaction. Once those terms are agreed on and approved by Party A’s client, written confirmation is sent to the client giving the details of the agreed terms. The transaction is consummated. Confirmations are also exchanged between Party A and Party B. At this point, a third independent party is not involved in recognizing and/or recording the transaction between Party A and Party B. The client is in the care of Party A. Should a problem arise between them, the client and financial institution that accepted the client will have to work it out; Party B is not involved in their problem. The terms agreed to are known by only three parties: the client, Party A, and Party B.

• CLEARING FACILITIES AND TRADE TRANSPARENCIES IN THE DERIVATIVE WORLD •

The Dodd-Frank Act discusses the need for clearing facilities and trade transparencies. The derivative product world is a perfect place to discuss it, as its products cover the entire spectrum.

There are products whose trades involve the transmission of confirmations that form part of a master agreement package or stand alone and after transmission require the confirmation sender to await affirmation from the contra party. These transactions are at the bottom of the list and are the least automated. (Note: These exclude the many daily transaction notifications known as “negative confirms” that do not require a response unless something is incorrect.) This process is expensive, labor intensive, and error prone. As only two people will see the confirmation details, the sender and the recipient, the chances of catching errors or detecting other problems early are minimal. It is only the buyer and seller, or the receiver and deliverer, or the payer and receiver, who know about the transaction’s existence. Therefore, confidence in the risk assessment and/or exposure analysis is low.

If the contra party to the trade doesn’t respond, the sender has an open transaction that may or may not be a valid transaction. This has a kind of “heads or tails” scenario. The parties do not know if the transaction is valid until the contra party is supposed to take some sort of action. The confirmation sender can call or send the contra party another confirmation in trying to get acknowledgement. Contracts could run for long periods of time, although the contra party may not exist by the tenor’s end. That is a long time to find out if the transaction is null and void.

Without the aforementioned transparency, transaction price versus actual market price verification is impossible. There isn’t a central independent pricing data source available for verification.

With each transaction standing alone, unilateral netting is not available. If the same security was traded by Dealer A twenty times, where Dealer A was buying from ten different broker-dealers and Dealer A was selling the same security to ten other broker-dealers, Dealer A would have to settle each trade individually with each contra party.

Each transaction must be monitored during its tenor to assure that periodic payments and other requirements are completed. This monitoring function could be performed by a central facility system instead of each participant performing its own.

Mark to markets, to assess risk and balance collateral deposits, during the life of the derivative product, is not universal. Where it exists or when it is called for, it is a manual process, and manual, one-at-a-time processes are error prone, inaccurate, and unreliable. In addition both parties must agree as to whether mark to markets is permitted on this particular transaction, the amount to be called for, the collateral being used, and the delivery date of same.

Payments that are to be made during the tenor of the derivative transaction must be collected. This includes prenegotiated amounts and method of payment, and could include acceptable currency and location payment is to be made to, as well as time and date. Periodic interest rate changes must be confirmed as to rate and applicable date. Accruals of interest must be verified and any differences reconciled.

Settlement at end of tenor creates a new set of problems. Settlement monies need to be agreed to, or if not, rebalancing using contract terms and applications must be performed to determine the settlement amount involved. This is time consuming and expensive as reconciling the difference often costs more than the difference is worth. With a central facility, there is ongoing interparty communication, and parties are notified by the central facility whenever there is any change to any part of the transaction.

Currency exchange transactions have their own life, as they could have a new set of potential problems separate and apart from the initial transaction. These include the source that determines the conversion rate to be used, the effective date for the conversion rate to be applied, the payment currency to be used, or the instruction of where and when the exchange of assets is to be delivered.

These details are supposed to be agreed to at inception. The central facility would be notified of terms and controls entries for both parties. Any discrepancies that may occur are highlighted and rectified by the parties quickly.

Customer Side

Once upon a time there were retail accounts and institutional accounts. Because it was inadvisable for a prudent person to leave assets that belong to other people in anything other than the safest location, custodial banks were permitted to settle transactions between the custodian and the trading financial institution on a delivery-versus-payment basis. Whereas retail had to settle trades in accordance with normal convention, which was T + 5 (trade date plus five days), T + 3 is now standard for most SEC-regulated products. CFTC, which is concerned with the public and their futures trades, is concerned with standard or initial margin that must be deposited immediately.

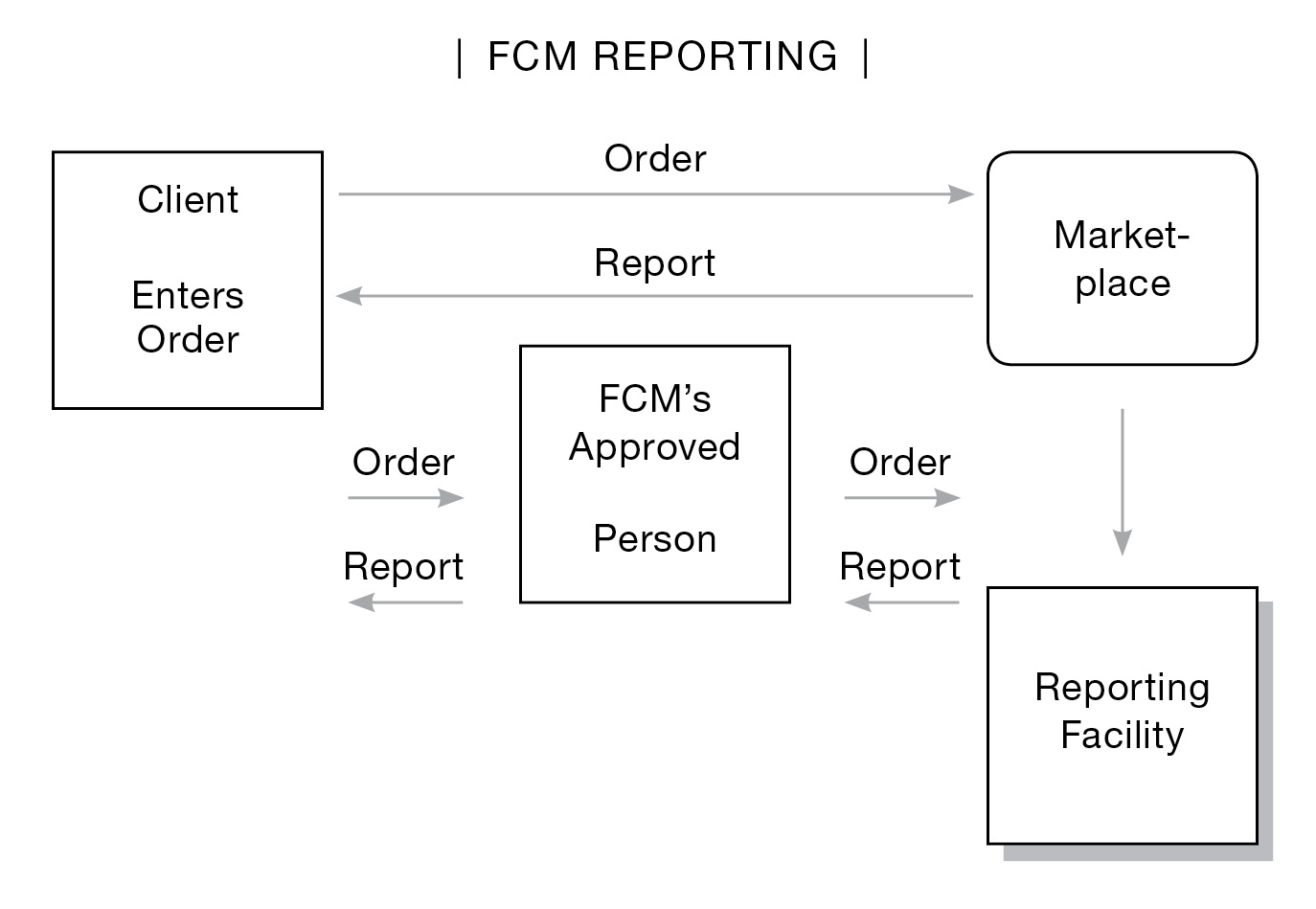

System Supported

A client calls her broker (Party A) and discusses a transaction she wants to perform. Assuming that the client has an account in good standing, Party A transmits the order to the marketplace. Once there, by either electronic trading venue or open outcry on a trading floor, the order is exposed to dealers and or other brokers. The order is executed and the price of the transaction is reported to Party A, the contra party or parties (the other side to the trade), and the reporting authority of that marketplace, which in turn broadcasts it to the public across many networks. The terms of the trade are known to anyone who cares to check on it. The client’s order could also be transmitted directly to the marketplace, with copies going to Party A, or to a client representative, who, after verifying the terms of the order to ensure they are in line with the client’s profile, forwards it to the marketplace for execution.

• THE MATCHING FACILITY •

From here on the product determines process.

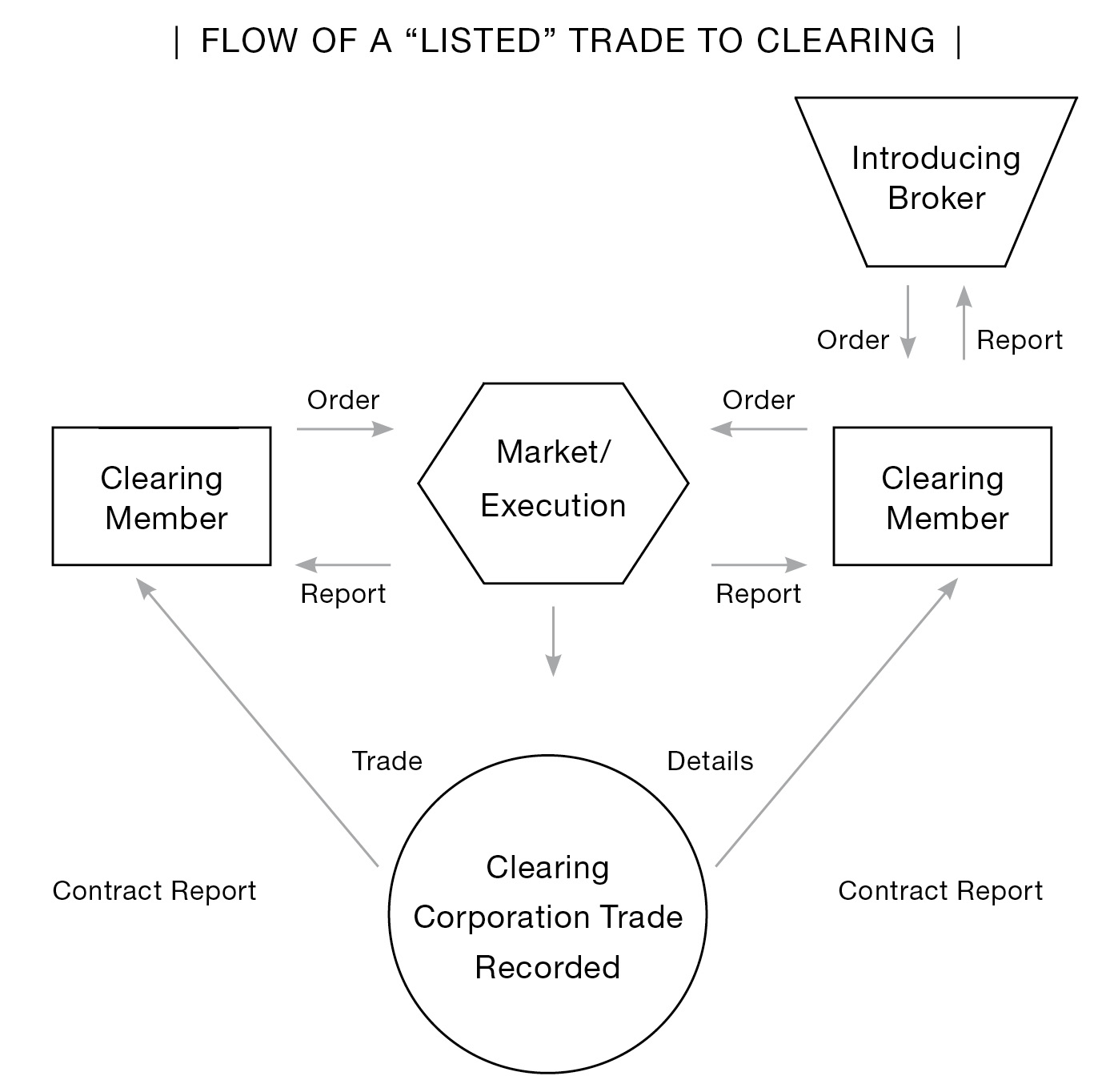

Those products traded on an exchange, such as the Chicago Board of Trade or the International Securities Exchange, have the terms of the trade captured at the point of execution and recorded as matched between clearing members. The trades executed by nonclearing members “give up” the names of their clearing member firms as only clearing firms have recognition at the clearing corporation.

At this point in the processing, the member clearing firms have “compared” the details of the trade and the clearing corporation has a record of the agreed-to transactions. Both firms now enter into the netting phase. This can entail bilateral netting for cash or bilateral netting for cash and securities.

• NETTING VS. NONNETTING •

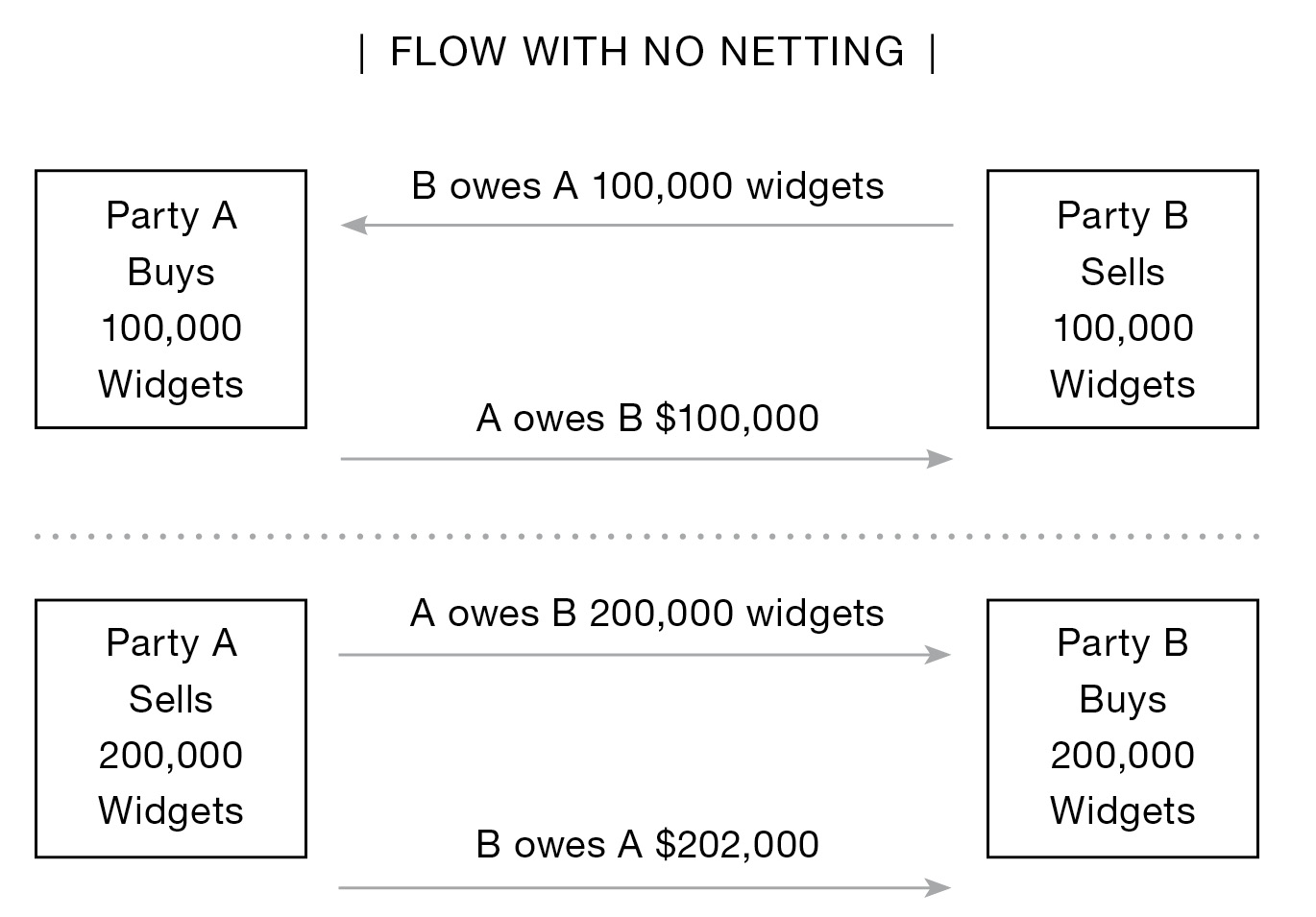

Each trade stands alone and must be settled independently of the others.

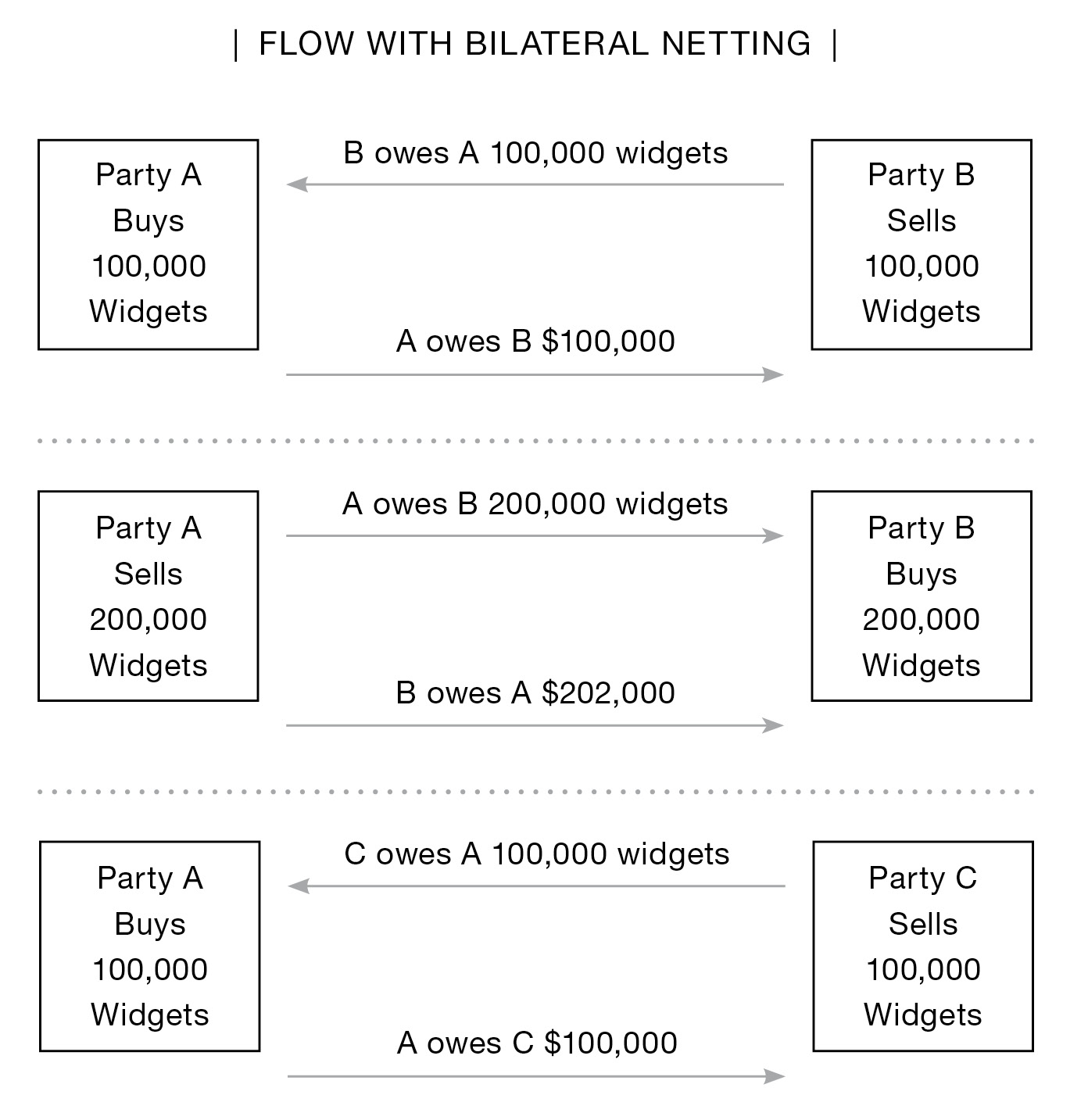

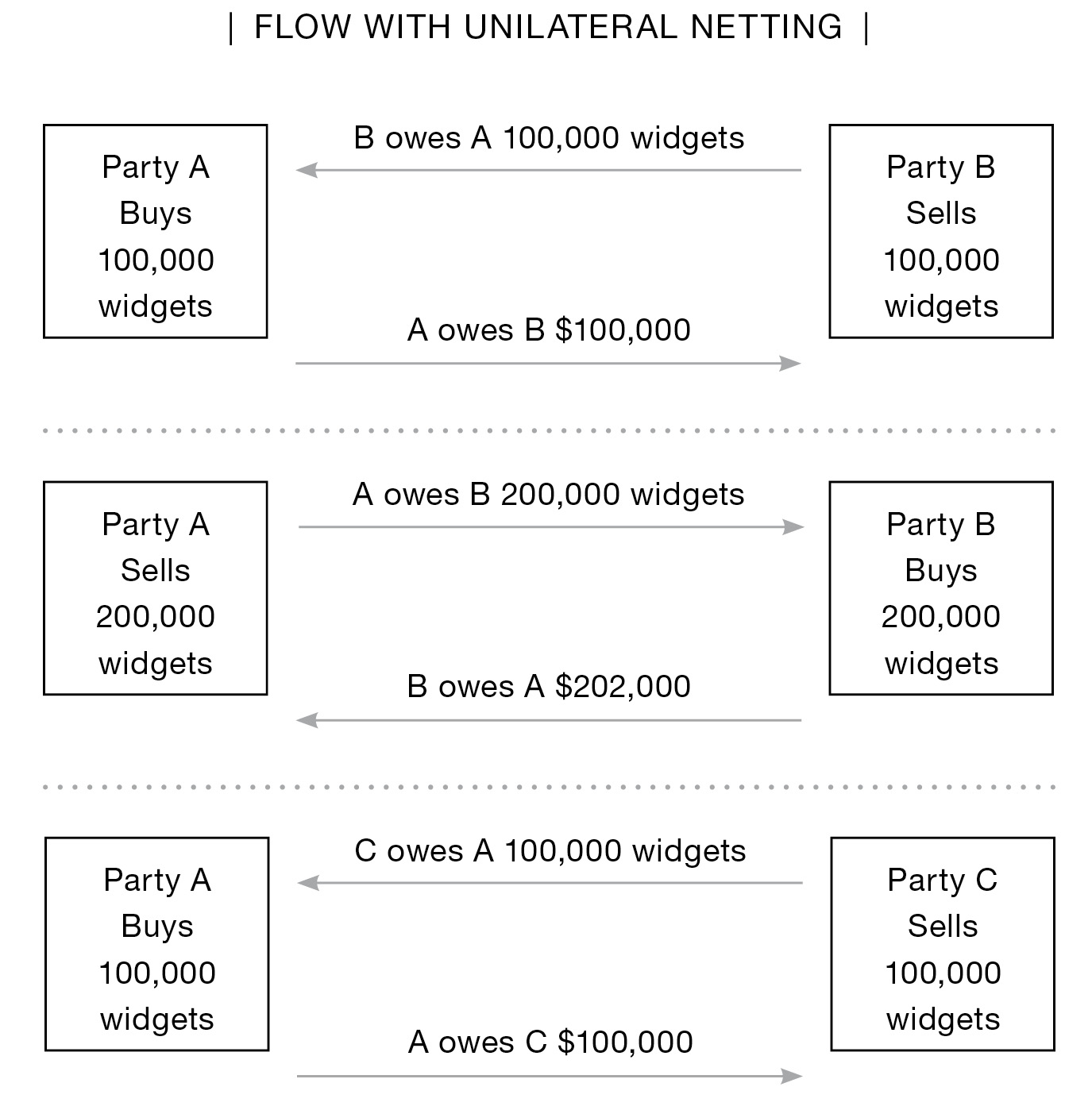

•BILATERAL AND UNILATERAL NETTING •

After Bilateral Netting

FIRST SCENARIO

Party A owes Party B 100,000 widgets

Party B owes Party A $102,000

SECOND SCENARIO, APPENDED TO PREVIOUS EXAMPLE

Party C owes Party A 100,000 widgets

After Unilateral Netting

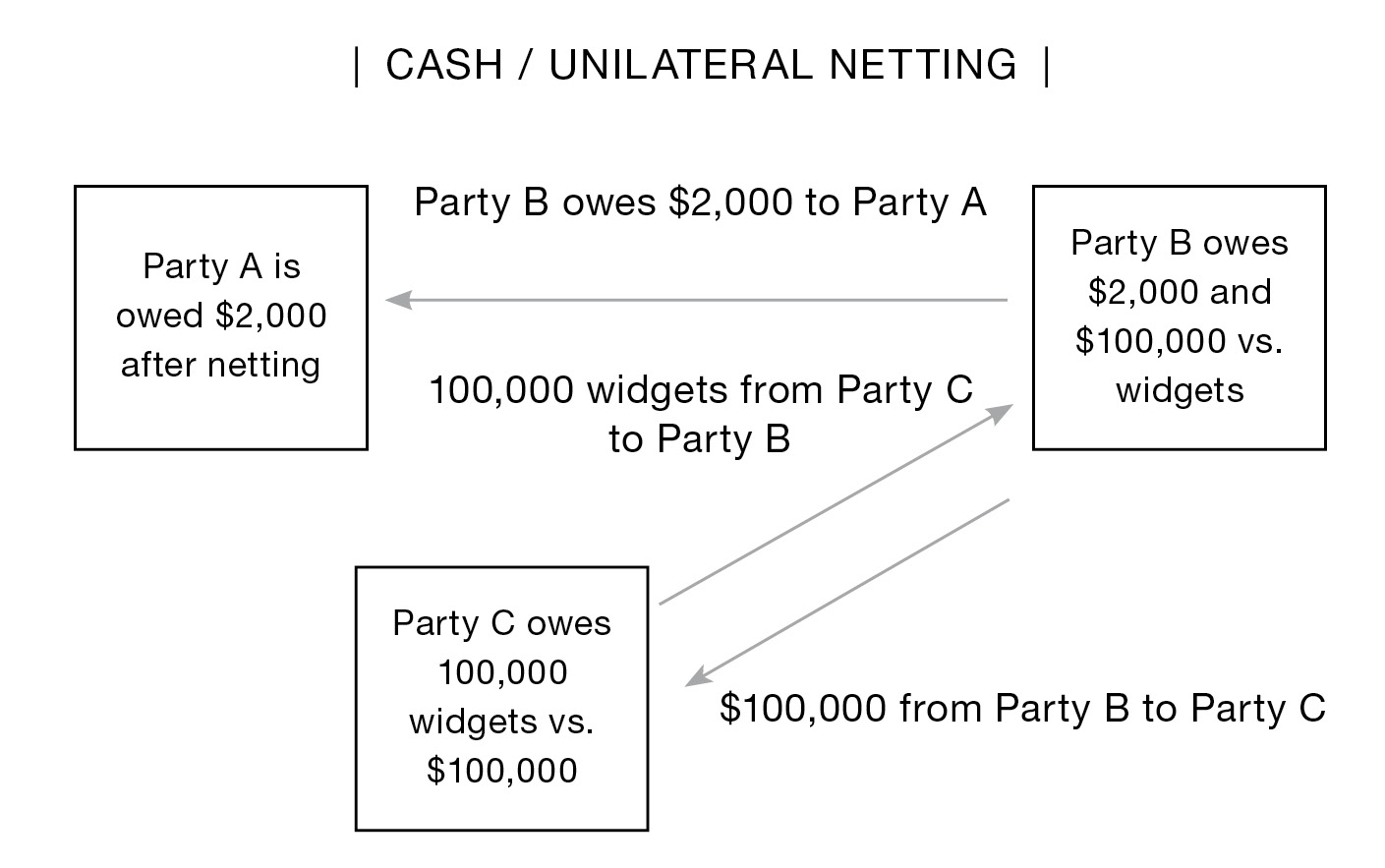

Widgets

Party A bought 100,000 widgets from Party B and 100,000 widgets from Party C. Party A sold 200,000 widgets to Party B. Party A’s widget balance is zero.

Party B bought 100,000 widgets more than it sold. Party C sold 100,000 widgets more than it bought. Party C owes Party B 100,000 widgets.

Cash

Party A bought $100,000 worth of widgets from Party B and $100,000 worth of widgets from Party C. Party A sold $202,000 worth of widgets to Party B. Party A is owed $2,000.

Party C is owed $100,000 from its sale of widgets to Party A. It will settle with Party B.

Party B owes $202,000 from its purchase of 200,000 widgets from Party A and is owed $100,000 from its sale of 100,000 widgets for a net $102,000 that it owes. Party B will pay Party A $2,000 and Party C $100,000.

All of the above calculations are processed electronically by the clearing facility.

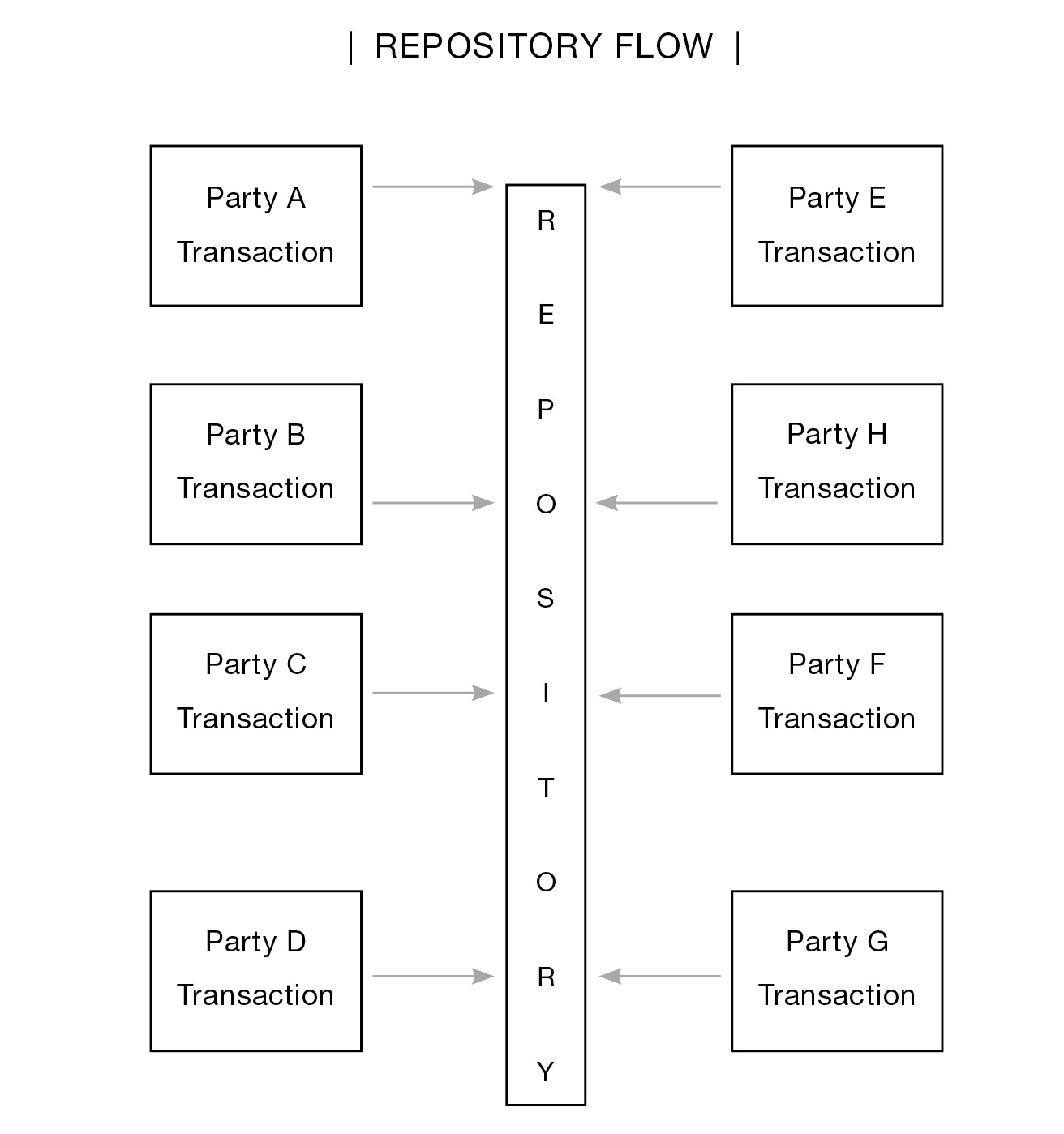

• A REPOSITORY •

A repository records the details of transactions, which include who the parties were to a transaction, the terms and requirements, trade date and settlement dates, and whether the details of the transaction are the same for the contra parties.

SUMMARY OF BENEFITS OF A CENTRAL REPOSITORY

- Independent third party is a witness to the transaction. The details of the negotiated contract reside on the records of the repository.

- The transaction input from the contra parties is captured in one location. Differences can be addressed immediately.

- Transactions in which both sides agree are recorded.

- Unmatched trades are carried that way until resolved or deleted.

- The third-party repository reports status of transactions to contra parties.

- Problem items are dated and aged.

- Price verification against actual market prices or similar derivatives can be accomplished.

- Confidence in prices and market is improved.

- Entitlements as required by the contract are easier to track with the repository tracking required entries.

- Cash movement entries are netted, simplifying the process by removing redundancy (where permitted).

- A financially or operationally troubled contra party is easier to detect.

- Auditing—internal and external—is easier to perform, more accurately, with less chance of “surprises.”

SUMMARY OF USE OF A CLEARING CORPORATION

- Transaction matching and comparison. Transaction locked in.

- Transactions that do not compare are dropped off system if not resolved in set time. Cannot have one side of transaction believing it is good and the other side believing it is not.

- Unilateral netting reduces entries to a minimum.

- Money and contract balances roll forward.

- Clearing corporation becomes central contra party to all compared trades.

- Clearing corporation forwards delivery/receive instruction to participants.

- Price transparency for regulators and interested parties.

- Auditing: Firm positions checked against clearing corporation.

- Differences detected on a timely basis.

- Transactions unwound in case of default and rebalanced without defaulting party and its contra firms.

SUMMARY OF USE OF CLEARING CORPORATION WITH TRANSACTION GUARANTEE

- Same as clearing corp without guarantee except for #10.

- Member firms maintain deposits.

- All compared transactions guaranteed by clearing corporation.

SUMMARY OF SETTLEMENT

- Trade for trade through custodian or clearing bank.

- Clearing corporation balances orders.

- Physical receiver vs. deliverer (commodities).

- Electronic entry through clearing banks (mortgage backed).

- Clearing corporation electronic transmission to depositories.

- Products such as options expire but their cash balances carry on with remaining products.