CHAPTER 2

OVERVIEW OF THE DEBT MARKET

The debt market forms the base for many of the products we will be discussing throughout this book. The market actually serves two purposes. The first is that many derivatives products use as a base the underlying issues that trade in this market, such as Treasury debt instruments. The second is that many of the derivatives products discussed in this book trade in the debt markets themselves. Collateralized mortgage obligations are an example. This chapter will focus on the debt instruments operating in that market.

• THE GLOBAL ECONOMY •

Everyone is connected to the debt market in some way. Individuals and governments both come to the market to borrow funds.

On the other side of the equation are the lenders, many of whom are also borrowers. A lender’s business model is to borrow other people’s money at one interest rate so that it can lend the same money to others at a higher interest rate. Paying an interest rate for the funds that is less than the rate received means a profit. The duration of these borrows ranges from overnight to decades.

The additional payment made by the borrower for the use of these funds is referred to as interest. The amount of interest charged by the lenders depends on several factors. The three primary factors are: the availability of funds, the risk that the borrowed sum may not be returned, and the length of time the borrowed funds will be outstanding. Therefore, interest cost can be looked at as another commodity or another product.

Since interest rates change and the timing of interest payments to the lender can differ, there is a market to trade interest rates and/or interest payments. If supply of funds exceeds demand for funds, interest rates will fall; whereas, if demand for funds exceeds the supply of funds, interest rates will rise. This symmetry excludes government intervention. The supply of funds is affected by monetary policy and the willingness of lenders, in general, to offer funds. In the global economy, economic events in one part of the planet may cause economic reactions in other parts, which in turn affect not only major corporations’ activities but even individuals’ daily lives.

Take this simple exercise:

Assume a local manufacturer makes a $5.00 product. The manufacturer buys $2.00 worth of material per product from a company two towns away, and spends $2.00 on labor, etc., therefore earning $1.00 profit for a total revenue source of $5.00—all of it domestic. Somewhere in some country on another continent is a company that makes the same material, and the domestic manufacturer can acquire the material from this foreign vendor for $1.25 per product. How long would it be before the manufacturer would switch vendors? The manufacturer would have the ability to see its profit increase from $1.00 to $1.75 per unit. If this manufacturer doesn’t do it, its competitors will.

Let’s make it even more realistic by looking at the variables. The manufacturer has to have a factory, which raises a lot of issues. Is the factory owned outright or is there a mortgage? What rate of interest is being paid on the mortgage versus the current rate? Does the manufacturer carry inventory? How is it paid for? Is it pledged against a loan; at what rate is it financed? Does the manufacturer have long-term debt, and if so, what interest rate is being paid? What is the current going rate for this class of debt? Are the bonds callable? Would it be beneficial for the manufacturer to call the debt in and pay for it with new debt at a lower interest cost? Is the company using its funds and resources to its best advantage? These questions, and many more that the company faces every day, assist it to better manage its businesses. As interest is an expense, it chews away at profits. And a company’s use of cash, owned or borrowed, is a very dear commodity—perhaps now more than ever.

• THE FINANCIAL CRISIS •

The financial markets, like any other markets, are vulnerable to abuse. The most recent example is the financial crisis that began late in the last decade. There are many fingers pointing in different directions as to who is to blame. Many people made a lot of money; many more lost. Among the abuses were high-risk loans. It will suffice to say that loans were made to individuals who couldn’t afford them, to purchase homes they couldn’t afford, at inflated prices the homes couldn’t sustain. As the housing market began to cool and housing prices started to fall, homeowners found themselves with outstanding mortgage amounts that exceeded the value of their homes.

Many of the homeowners walked away from their obligations. Those houses were eventually sold by the mortgage companies, depressing the housing market even more. On top of this, many “flippers” began buying homes with the intention of dumping them in a few months when homes price rose, capturing the profit. Instead, as the prices were falling, those speculators wound up dumping these investments on an already weak market, causing the prices to fall even faster. Many of these mortgages were securitized into derivative products. By the end of the downward spiral, it was a global disaster.

The financial crisis has brought a slew of regulations in the United States under the Dodd-Frank Act, also known as the Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, many provisions of which are still pending. In addition, the European Central Bank and its seventeen member states found themselves in a sovereign debt crisis with the possibility of countries’ defaulting, which led to European Market Infrastructure Regulation (EMIR). These regulations are designed to head off another financial crisis.

As a law of physics states, each action has a reaction. Many banks and other financial institutions must raise the amount of reserves they are required to keep against their loans. Therefore the banks have less money to lend, borrowing becomes more difficult, and interest rates rise. The Volcker Rule, which is included in the Dodd-Frank Act, restricts certain financial entities from engaging in different types of proprietary trading, with the result that markets become less liquid. As that happens, traders face bigger risks in their proprietary (market making [trading against the public markets]) activity, and certain markets may become unattractive for trading due to the lack of liquidity and trading activity. In the face of a weak economy, different countries must take care to ensure continuity in the implementation of these actions.

• FIXED- VERSUS FLOATING-RATE DEBT INSTRUMENTS •

Lenders are always trying to find innovative ways to offer their funds at the highest possible return and yet acquire these funds at a rate that is attractive to the investor or other lending institutions. This search has led to many interesting and complex products. Yet there are still many investors who want straight uncluttered simple debt, such as bonds, notes, and short-term paper (known as commercial paper). These simple instruments pay interest payments periodically, and their principal sum at maturity. However, during the life of the debt instrument, the owners of the issuer’s loans are at risk due to no fault of the borrowing entities.

If interest rates in general rise, the prices of those fixed-interest instruments already outstanding decrease, in order to remain competitive with the yield of newer products coming to market. Therefore, should the bond owner have to sell these bonds before maturity, and while interest rates are higher than when the bonds were issued, the bond owner would suffer a loss.

Here’s an example:

As the interest rate is fixed on a bond with a 5 percent “coupon” rate, the bond is expected to pay 5 percent of its principal amount annually. If interest rates in the debt market rise in general so that new bonds coming to market carry a 6 percent coupon, the value of the 5 percent bond has to fall so that its return on investment is comparable to the 6 percent newly issued bonds. The bond is still paying the 5 percent annual interest owed, but it is now priced so that it is yielding the equivalent of the newly issued 6 percent bond.

The reverse is true also; if a 5 percent bond is trading in the markets when interest rates fall and newly issued equivalent bonds are carrying a lower interest rate, the price of the 5 percent bond will rise so that its return is competitive. In both cases the bond is paying 5 percent of its face amount, with a $1,000 bond paying $50 a year. However, if newly issued bonds, equal in quality and longevity, are trading at their face value but paying out at a different rate due to interest rate changes, the outstanding fixed-income instrument’s price must change to remain competitive in the marketplace.

There are investors who value the principal of their investment more than the income it produces. In an attempt to attract these debt investors, wanting not to expose their capital investment to interest rate swings, borrowers will issue floating or adjustable rate instrument bonds. The interest rate paid by these instruments taps into the rates at which short-term debt instruments are borrowing. As short-term rates change, the rate of interest paid on these longer-term bonds is reset periodically to reflect current debt market conditions. As the interest rate paid on newly issued debt rises or falls, the interest rate on these outstanding instruments is adjusted accordingly. It is also important to remember that the real or perceived financial strength of the issuer of the debt also affects the price of its debt instrument.

• CALLABLE BONDS •

Bonds may contain a call feature: this allows the issuer to retire a bond earlier than the debt’s maturity date. Usually a bond with a call feature will contain a premium price at which the bond will be called.

Here’s an example:

A thirty-year bond has a call feature that allows the bond to be retired (called in) after twenty years, but it may be called at a premium price. The premium will diminish over the ten years that are between the call date and the maturity date of the bond. Furthermore, call features in debt instruments work for the benefit of the issuer, not the investor. An issuer will call bonds in either when it can refinance those loans for less cost, or when it simply does not need the borrowed funds any longer. The former is brought about as general interest rates have fallen and money is easier to borrow. If the issuer can finance the loans for less cost, it means the current bondholder will have the bond called in and then, if desired, reenter the debt market buying other bonds, of equal ratings, that are paying less than the bonds that are being retired.

The call feature may permit a full call, the retiring of the entire issue, or a partial call. In the process of the full call, the bonds must be surrendered by the bond owners by a predetermined date. The issuer’s agent will pay the bondholders the required amount when the bonds are retired. On the due date of the call, the bond will stop paying interest, and if any bonds are not retired on time, the issuer can continue to use the borrowed funds free of any interest cost until these bonds are submitted for retirement. Bond positions that are maintained by industry institutions for proprietary use or for their clients will deliver the bonds to the issuer’s agent by the due date so they can pay the debt owners their due.

In the case of a partial call, the main repository, the Depository Trust Company (DTC), will allocate the amount being called among all of their members who have those bonds in position. Those member companies, in turn, will allocate their required portion of the call among their clients’ and proprietary accounts that have those bonds in their positions. Therefore there is a chance that a bondholder may have his or her bonds retired early, or have them not retired.

Naturally, most bond owners do not want their bonds retired early, as they would miss out on the higher interest income they could receive. Broker-dealers and other financial institutions are under strict rules to carry out their fiduciary responsibility in this allocation process fairly and in accordance with established procedures. On a partial call, the quantity being called may be prorated against those customer accounts holding the bonds. As an investor, it is important that you trust the firm you are doing business with to make sure they are following proper rules and regulations as to the allocation of calls.

The Rule-of-Thumb Method

In dealing with callable bonds, the bond dealer must offer the bonds to the investor at the lower of yield to maturity or yield to call price—whichever is less advantageous to the client. Let’s take a look at an example using the rule-of-thumb method—a quick, but inaccurate way of getting near the correct answer. (We’ll look at the actual computation for yield to maturity later in the book.) Using the rule of thumb method, a $1,000 5 percent thirty-year bond is issued that is callable in twenty years at a price of 105 ($1,050.00). The bond is currently trading at “97” ($970.00).

Rule-of-Thumb Calculation (ROT)

- Calculate the difference between the market price and the value at maturity, divided by the bond’s years remaining. The answer is the annual amortization amount (for a bond priced at a discount) or annual depletion amount (for a bond priced at a premium).

- Add (in the case of a bond trading at a discount) or subtract (in the case of a bond trading at a premium) the amortization/depletion amount to the annual bond’s interest payment to get an adjusted payment amount.

- Add the current value and the value at maturity together and divide by two to obtain an average price over the bond’s remaining life.

- Divide the adjusted payment amount by the average bond price to get the ROT.

Yield to Maturity

|

$1,000.00 |

—Value at maturity |

|

|

Less: |

$970.00 |

—Current market value |

|

$30.00 |

$30 amortized over 30 years = $1 per year

Average theoretical value over the life of the bond: = $1,000 + $970 = $1,970/2 (for average) = $985

$5% interest on $1,000 bond = $50 + $1 (annualized amortization) = $51.00

51/985 = 5.17%

Yield to Call

|

$1,050.00 |

—Value if called |

|

|

Less: |

$970.00 |

—Current market value |

|

$80.00 |

$80 amortized over 20 years = $4

Average theoretical value up to call = $1,050 + $970 = $2,020/2 (for average) = $1,010

Annual interest of 5% on $1,000 bond = $50 + $4 (annualized amortization) = $54

54/1010 = 5.34%

Using the above example, the client would be quoted a basis price of 5.17 percent. If the bonds should be called at the twenty-year mark, the client would do better. By using the worst outcome as the quote, the floor is set by which the client can do no worse, but get that return or better. Bear in mind that these yields are obtained through corporate actions and not by market activity. Once the bonds are acquired, selling them in the market will involve profit or loss on the total transaction. This computation has nothing to do with the rate of return on the investment.

Sinking Fund Provision

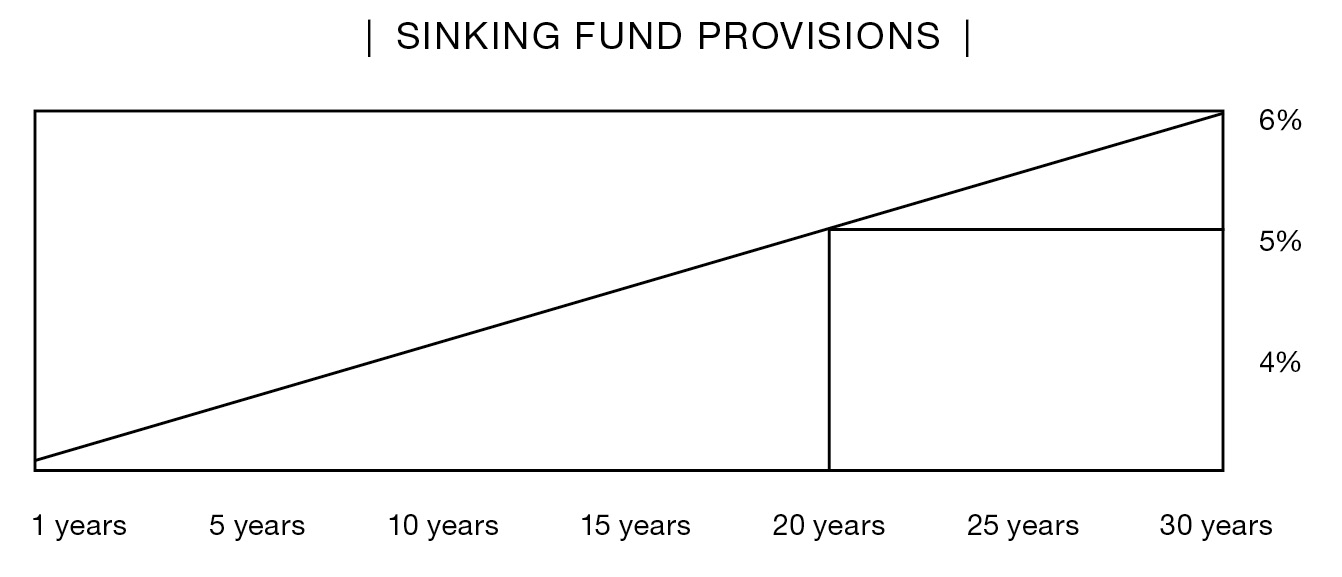

There are some investors who may, as part of a strategy, want their bonds to be called early, since the normal yield curve slopes upward the longer a debt is outstanding. Let’s look at an imaginary investor, Mr. Ian Long, who wants to invest a sum of money for twenty years. Using the chart below, and assuming a straight-line yield curve, Mr. Long could acquire a twenty-year instrument and receive slightly more than a 5 percent rate, or he could buy the thirty-year bond and receive 6 percent interest, hoping to be called at twenty years.

Some bonds are issued with a sinking fund provision to accommodate investors like Mr. Long. This fund allows the issuer to retire the bonds earlier by buying them in the open market and paying for the purchases from the company’s earnings. Under the provision of the sinking fund, the issuers are not permitted to pay more than face amount for the bonds. When the sinker is active, participants surrender the bonds to the issuer’s agent, which will retire enough of the particular bond issue to satisfy the sinker’s provision.

Refunding

Refunding must be looked at from the point of view of the issuer as well as from the point of view of the investor.

Investor’s Point of View

The bond issuer exercising a call feature may offer to pay cash for retiring the bonds, or go through a refunding whereby the bondholder is offered a new bond in place of the called one. This refunding applies to the relationship between the investor and issuer. Refunding by the issuer, who is using a new debt to replace the old one, may have incentives for the bondholder to accept the refunding. One such enticement is to issue the new bond with an interest rate below the existing bond’s rate, but slightly higher than competitive bonds that are trading in the market. As the bonds are about to be retired, the current bondholders will be receiving cash represented by the call price. The bondholder may reinvest this cash in any product he or she wants to acquire. The most attractive investment may be the issuer’s new offering.

Issuer’s Point of View

To the issuer who is offering substitute bonds to the current bond holders, they are attempting to refinance the older debt on more favorable terms yet sweetening the offer so as to retain the previous owners’ investment.

If the issuer is retiring one bond by offering a new bond in the marketplace and not directly to the previous owners, that would be referred to as refunding also. Simply put, the retiring of one debt by issuing another is refunding. The U.S. Treasury Department refunds the Treasury bills every week. They retire Treasury bills that are maturing by paying for them with Treasury bills that are brand new. If they issue more than they retire, they will expand the national debt; if they issue fewer bills than they are retiring, they reduce the national debt. This type of refunding does not include the owners of the older bond. They simply surrender their maturing bonds and receive the payoff proceeds. The new bonds are offered in the market to anyone who wants to acquire them.

• PUT BONDS •

The term “put bond” is deceiving. It should mean that the bondholders have a right to “put” the bond back to the issuer, given certain terms and conditions. Few bonds are issued with this provision; however, a putable bond carries a mandate that the bond be returned to the issuer. If the issuer has the right to mandate that the bondholder must put the bonds back to them, that is the same as the call feature of a bond.

Let’s look at the call feature more closely. If a corporation comes to market and wants to issue $10 million worth of thirty-year bonds based on the current interest rate, the company must pay 7 percent. At 7 percent of $10 million, the bond is paying $700,000 a year in interest, and over thirty years that will be $21 million in interest. If interest rates should fall over time, so that this company could now issue a 5 percent bond and the investors would be able to get par, it can now be in a position to issue a $10 million 5 percent bond. Assuming that one is also going out for thirty years, that will cost the company $500,000 a year or $15 million in thirty years. It would save $6 million by retiring the bond. There is some expense involved in the retiring or reissuance of bonds, of course, but $6 million saved covers a lot of expenses.

Another reason for calling in bonds is the difference in interest rates as the thirty-year bond goes through its life. The thirty-year bond will be paying 7 percent for as long as it’s outstanding. After fifteen years, the corporation that issued the thirty-year bond may be able to issue a fifteen-year bond paying less interest, let’s assume the proverbial 5 percent. By calling in the thirty-year bond that has fifteen years to go, and issuing a fifteen-year bond that is carrying a 5 percent coupon, the company can save $3 million a year. Therefore, in the case of a callable bond holder, the threat of a bond’s being called is not only caused by a drop of interest rates, it could be caused by a change in the bond’s longevity as it goes along the yield curve from thirty years to fifteen years to zero.

• SINKING FUND •

Some bonds are sold with the understanding that a sinking fund has been activated. A sinking fund is the ability of an issuer to buy its bonds back out of earnings. Therefore in the above example, a corporation issuing a thirty-year 7 percent bond, with a sinker in force, can buy the bonds back whenever it wants, depending on the terms of the sinker, and retire the bonds at the current market price.

Not all bonds have sinkers. The advantage to buying a bond with a sinking fund is that if the issuer bought back early in the bond’s life it will pay as long as it at par or less, and the owner of the bond will receive a high rate of interest for a short period of time—much better than if he or she had invested in a short-term bond. Some bonds are traded at dollar prices, which means they settle in currency. A price in the United States of a bond trading at 96 would be $0.96 on a dollar, so a $1,000 bond would cost $960. A bond trading at 101 would be $1,010.

Bonds that trade below their principal amount are said to be trading at a discount. Bonds that trade above their principal amount are said to trade at a premium. As the interest rates change due to many economic conditions, the price of bonds will change accordingly. In a fixed-income instrument, as interest rates rise bond prices fall; as interest rates fall bond prices rise. Since the bond can’t change its interest rate to reflect the current interest rates, it must adjust for the difference somehow.

• HOW DEBT INSTRUMENTS TRADE •

Fixed-income instruments will change their price to accommodate the changing in interest rates. Some debt instruments trade at basis prices. The term “basis price” is short for a yield-to-maturity basis, which means that if the buyer of that particular bond holds the bond to maturity, that is the rate of return they would receive. It includes the interest received, plus any amortization of the difference between the purchase price and par, assuming the bond was procured at a discount, or the depletion of the amount that the customer paid over the bond’s face amount if the bond was bought at a premium.

Some debt instruments, like municipal securities and U.S. Treasury bills, trade on a yield-to-maturity basis. That means that the price they’re paying has to be converted from the yield to maturity or the basis price into a dollar price. Generally speaking, if the basis price is higher than the coupon rate, the bond is trading at a discount. If the yield to maturity is less than the coupon rate, the bond is trading at a premium. For example, if a bond has a 6 percent coupon and is yielding a basis price of 5.9 percent, the customer must be paying more than the face amount to get the reduction in the yield. If that same bond has a basis price of 6.15, the customer would be getting the yield to maturity of 6.15, or 6.15 percent on their money. Since the bond only pays 6 percent interest they must be paying less than par to get the increase in the rate of return.

The relationship between the interest rate or coupon rate of the bond and the basis price is very important to understand, especially when discussing credit derivative products. The closer those two are to each other, and the closer the bond is to trading at par, the further the conversion to dollars will be from par. So an 8 percent bond trading at an 8.05 percent yield is trading very close to par. An 8 percent bond trading at 12.5 percent yield basis price is trading far from par and is trading at a deep discount to par.

• TAX ON INTEREST PAID •

Another feature peculiar to bonds is the tax or applicable tax on the interest paid. Concerning United States Treasury bonds, the interest paid is free from state and local taxes, but is taxed by the federal government. It may sound counterintuitive, but once again, the interest paid on debt issued directly by the federal government is taxed by the federal government but not taxed by state and local governments.

The interest paid by some municipal bonds is fully taxable, including by federal, state, and local governments; however, the interest paid by most municipal bonds is free from federal tax and, if you live within the state of issuance, free from state and local taxes. Therefore, for people who live in New York City, the city’s own municipal bonds are usually free from federal, state, and city taxes. That freedom from federal income tax is applicable across state borders also; however, once you cross the border, the bonds become taxable for state and local purposes.

Corporate bonds are fully subject to federal, state, and local taxes. Therefore people who buy tax-free bonds may be getting a small advantage, but the adjustment in the yield between a taxable bond and a tax-free bond normally includes in the calculation the tax rates of those various states. Concerning bonds issued by federal agencies, like Ginnie Mae and Freddie Mac, the interest paid on those bonds is fully taxable on the state, federal, and local levels.

• DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MUNICIPAL BONDS AND CORPORATE BONDS •

An important point to bring out regarding bonds is the issuance. At the point of issuance, U.S. Treasury bonds and corporate bonds have one CUSIP number. Municipal bonds, however, are issued in serial form. Because their various component bonds mature at different times, there are millions of municipal bonds outstanding. Therefore a customer buying your typical corporate bond on Monday, and telling a friend about it that night, might find that friend buying the same bond on Tuesday. However, should that investor have bought a municipal bond on Monday, and told his friend about it on Monday night, chances are that bond would no longer be available.

The corporate bond and the government bond form of issuances is called a “bullet,” which means the entire bond offering has one coupon rate and one maturity date. Municipal bonds, on the other hand, are issued in serial form; therefore, while the issue itself may be as large as a corporate bond, the individual bonds making up the total are relatively or comparatively small and would have their own coupon and maturity date.