Materials and construction techniques have come a long way in recent years and continue to be developed at amazing rates, driven by the high performance requirements of offshore and trans-ocean high budget racers. Unfortunately, some of the more exotic materials really are very expensive indeed; for the most part high performance comes at a high price.

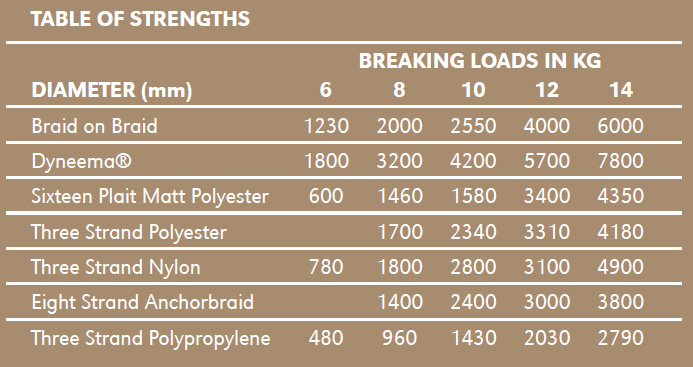

The main benefits of these high tech lines are their light weight coupled with high strength and low stretch. Indeed, for the majority of jobs on an average boat, strength is not something we need to worry about. If the line is thick enough for easy handling, it’s strong enough for the job. (This assumes sheaves of at least 5:1 diameter ratio and no kinks or sharp bends and careful knotting.)

The questions to be asked then revolve around the degree of stretch that is either required or is acceptable, and the preferred construction. However, one thing that must be remembered on the matter of strength is that should a permanent eye be needed in the end of a line (for example, to fit a shackle on a halyard), that eye should be spliced in, not formed with a knot. A good splice will retain over 80 per cent of the rope’s strength, but a knot will reduce the strength by up to 50 per cent. Frightening, isn’t it?

Polyester, sometimes referred to by the abbreviation PES, is available as a three strand laid rope, a plait, a laid core with plaited sheath, or as a braid on braid line. Finishes can either be smooth or slightly roughened for easier handling. It’s an excellent all round material for low stretch purposes such as halyards and sheets on dinghies and cruisers, where it’s both durable and relatively chafe and chemical resistant. It’s far from being the lowest stretch material available (25 per cent at break) nor is it the strongest (8g per denier), but for the average boatowner it represents good value for money in addition to being easy to handle and work.

Nylon (a contraction of New York and London, the two cities in which it was developed), has similar strength to polyester, but is stretchier (35 per cent extension at break). This makes it popular for anchor rodes and mooring warps, but exposure to ultraviolet light and sea water (or at least the contaminants in sea water) rapidly discolour it and stiffen it, making it awkward to handle. For that reason, its popularity is waning and many people are changing to polyester; however you should avoid pre-stretched polyester in situations where you would previously have chosen nylon for its stretchiness. Nylon is available in three strand form as well as the special eight strand anchorbraid.

Polypropylene, sometimes shortened to PP, is usually considered cheap and cheerful, being at the bottom of the rope price range and available in several colours – though if you look at the current range of braided rope colours this may not be so remarkable as when it was first marketed. Polypropylene feels quite hard when handled and the smooth versions are quite slippery. Staple spun polypropylene has a ‘hairy’ finish, which gives a better (if not comfortable) grip. PP lines are not particularly strong when compared to other synthetics, but they are light and float, making them useful for lines on lifesaving devices, but a menace to propellers.

Kevlar®, a trade name of Du Pont, is an aramid and was the first ‘exotic’ material used in rope making. It is light and almost three times as strong as polyester, but it is expensive and has proven to have poor durability in marine applications, being vulnerable to both ultraviolet light and abrasion. Kevlar® has largely been phased out by rope makers in favour of more recently developed materials.

Dyneema® is the trade name of DSM High Performance Fibers, and Spectra® is the trade name of Allied Fibers; so far as the yachtsman is concerned, these two high modulus polyethylene fibres are the same. They are the material of choice for high performance racing craft, having high strength (35g per denier, or more than four times that of polyester) and low stretch (only 3.5 per cent at break), but are expensive. The high cost, though, is outweighed on these boats by the benefits of Dyneema® and Spectra®, which include durability and resistance to ultraviolet light. They are always made up into core and sheath-style lines, and are usually spliced by rigging experts rather than simple seamen as it’s a tricky process.

Liquid Crystal Polymer Fibre (LCP), often referred to as Vectran® (a trade mark of Celanese), is a beautiful gold-coloured material that costs about as much as gold. It’s light, only stretches 3.3 per cent at break, has high resistance to temperature, but is only moderately abrasion resistant. It is so affected by ultraviolet light that it is stored away from all daylight prior to being incorporated into a rope’s core. It’s three times as strong as polyester, which is rather less than Dyneema® or Spectra®, and costs (currently) around 20 times as much.

PBO (polyphenylene-2, 6-bezobisoxazole), or Zylon® (a trade mark of Toyobo Co), is the top of the range of the exotics. It is over five times as strong as polyester with 3.5 per cent extension at break, but it hates ultraviolet light and chemicals, although it doesn’t mind heat. It costs a staggering 35 times as much as polyester at present, thus putting it into the realms of fantasy for most ordinary sailors.

This is a fact far less widely recognized than it should be. Any knot will seriously reduce the strength of the line it is formed in, and to demonstrate this English Braids carried out a short series of tests exclusively for this book.

It was found that a Bowline reduced the strength of a line by 30 per cent, a Figure of Eight loop by 28 per cent, and a Reef Knot by 50 per cent. Considering the number of occasions in which we use these knots on board our boats, these are pretty serious numbers, and should be borne in mind when selecting both ropes and knots for particular jobs.

Even though knots do seriously reduce the ultimate strength of all ropes, it remains true to say that while we cannot ignore a rope’s breaking strength, it is generally more important to select the right material for a particular use, coupled with a comfortable diameter for handling. If the material is right and you select a diameter that’s easy to handle, the strength will be adequate.

The most popular choices for sheets and halyards are either braid on braid lines or sixteen plait polyester, which has a roughened surface that is very good to handle and grips well on winch barrels. The braid on braid needs to suffer a little bit of surface abrasion before it loses its superficial gloss and becomes as pleasant to handle as the sixteen plait. This is more apparent with sheets than halyards, and also, while sheets are commonly fastened to genoa clews with bowlines, halyards are shackled to the heads of sails, requiring an eye in the end of the halyard. It is far easier to make a good eye splice in braid on braid than the sixteen plait, making braid on braid the favoured choice for halyards. Incidentally, slight roughening of the cover on a braid on braid line does no real harm to the rope: it is the core that supplies the rope’s strength.

On more performance orientated craft, Dyneema® or Spectra® ropes are growing in popularity, at least for halyards, as they stretch so little and maintain a good tight luff. In contrast, many ‘traditional’ (which usually means gaff rigged) boats are using buff coloured three strand polyester matt ropes as they are good to handle and look very much like old hemp or cotton lines.

While many boatowners happily anchor using a good length of chain coupled with a nylon three strand laid rode, the eight plait anchor braids are a much better bet as they have been designed specifically for the job. These lines still require a generous length of chain cable next to the anchor to ensure a good horizontal pull and to take most of the abrasion on rough ground, but they are much less likely to snarl up and cannot twist into kinked knots as a laid rope twisted the wrong way will do. Like all plaited or braided ropes, these anchor braids should never be coiled in the neat loop associated with laid ropes: rather they must either be put into figures of eight or, better, flaked down in a series of back and forth runs, each layer at right angles to the lower one. Coiling a plaited rope will induce twist and it will snarl up as it tries to run out, whereas a laid rope needs to be twisted (in the direction of its lay) as it is coiled to ensure it does not tangle up. These two constructions produce lines with almost opposite properties in this respect.

An anchor braid will also have better ‘give’ characteristics for absorbing shock loads than a laid line will. When lying at anchor in strong winds and rough water, the shock loads on the rode and on the deck fittings can be substantial and the braided construction copes with these by virtue of the springiness of its construction as well as the elasticity of the nylon itself. A laid rope has far less constructional ‘give’.

Capstans and windlasses should be able to cope equally well with either type of construction.

When it comes to mooring lines, it’s common to see all sorts used – laid, braid on braid and anchor braid – in nylon, polypropylene or polyester. All too often they are offcuts from old headsail sheets that have seen better days. Though it’s understandable that owners use such lines rather than just put them in the rubbish bin, it’s not advisable. If the lines have reached the end of their working lives for one purpose, it’s likely that they will be no better for another, especially the serious task of securing your valuable investment to the dock.

There are, of course, arguments in favour of each material – nylon, polyester, polypropylene – but, after cost, the thing to look for is ultraviolet resistance, since these are the lines that will be exposed to the sun for most time. It’s a sad fact that the majority of boats spend far more time moored than at sea, so their docking lines are the most heavily used.

Not surprisingly, some consideration has to be given to the handling and care of all these high tech ropes.

DO:

![]() Keep them coiled or hanked neatly to prevent tangling.

Keep them coiled or hanked neatly to prevent tangling.

![]() Run them out carefully to avoid kinking and knotting.

Run them out carefully to avoid kinking and knotting.

![]() Coil laid ropes in clockwise loops (for right-hand lay) and use figures of eight

for braids.

Coil laid ropes in clockwise loops (for right-hand lay) and use figures of eight

for braids.

![]() Wash out salt, sand, grit and mud, which will otherwise chafe and destroy the fibres.

Wash out salt, sand, grit and mud, which will otherwise chafe and destroy the fibres.

![]() Try to hang coiled or hanked ropes in a locker rather than dump them in an untidy

heap.

Try to hang coiled or hanked ropes in a locker rather than dump them in an untidy

heap.

![]() Protect all lines from chafe.

Protect all lines from chafe.

![]() Use eye splices rather than knotted loops for permanent or high load attachments.

Use eye splices rather than knotted loops for permanent or high load attachments.

![]() Use blocks whose sheaves have diameters in the ratio of at least 5:1 with that of

the ropes they will carry.

Use blocks whose sheaves have diameters in the ratio of at least 5:1 with that of

the ropes they will carry.

![]() Ensure the rope fits comfortably into the groove of the sheave it’s passing round.

Ensure the rope fits comfortably into the groove of the sheave it’s passing round.

![]() Seal and whip ropes’ ends. Braided sheaths in particular fray very quickly.

Seal and whip ropes’ ends. Braided sheaths in particular fray very quickly.

![]() Leave high tech lines exposed to high levels of ultraviolet light for long periods

of time.

Leave high tech lines exposed to high levels of ultraviolet light for long periods

of time.

![]() Kink or twist any type of rope.

Kink or twist any type of rope.

![]() Don’t stand or walk on ropes and lines.

Don’t stand or walk on ropes and lines.

![]() Surge lines, particularly polypropylene ones, too fast around winches or cleats or

they’ll melt.

Surge lines, particularly polypropylene ones, too fast around winches or cleats or

they’ll melt.

![]() Use rope stoppers that are likely to crush the rope’s core; some of the more exotic

materials are prone to damage of this nature.

Use rope stoppers that are likely to crush the rope’s core; some of the more exotic

materials are prone to damage of this nature.

Well organised running rigging makes sailing safer and easier