1. CHINCOTEAGUE NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE

WHY GO?

Every spring and fall, millions of birds migrate between cold, northern environs and temperate and tropical homes in Central and South America. En route, their needs are simple: an occasional place to rest and food to nourish. Wildlife biologists at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, on the southern tip of Assateague Island, have engineered a deluxe ornithological wayside for the winged travelers. Entire sections of beach are closed during nesting season for such species as the endangered piping plover and Wilson’s plover. On small, man-made earthen mounds rising in the middle of bayside lagoons, waterfowl perch and feed, protected from predators. As the human hand tinkers with wildlife balance, real drama plays out in the daily life of birds and land animals–and it’s on display for all to see.

THE RUNDOWN

Start: Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop: Herbert H. Bateman Educational Center on Beach Road; Beachfront Backpack: Toms Cove Visitor Center

Distance: Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop: 7.5-mile loop; Beachfront Backpack: 25.0 miles out and back

Hiking time: Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop: about 3 hours; Beachfront Backpack: about 10 hours

Difficulty: Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop is easy. Beachfront Backpack is moderate due to length. Between May and Sept, mosquitoes, greenhead flies, deerflies, and ticks make exploration of Chincoteague’s interior shrub and maritime forest inadvisable, especially at dawn and dusk. Long-sleeved shirts, pants, and bug netting, plus bug spray, can alleviate this problem.

Trail surface: Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop: A network of paved roads, dirt roads, and sand jeep trails lead hikers to a wide ocean beach, maritime forest of oak and pine, low dunes, and saltwater marsh. Beachfront Backpack: Sand and surf along a wide ocean beach.

Land status: National wildlife refuge and national seashore

Nearest town: Chincoteague, VA

Other trail users: Cyclists, anglers, over-sand vehicles, horseback riders, and hunters (in season)

Accessibility: Fully half of the refuge’s trails are paved, including the Wildlife Loop, Swan Cove Trail, and Black Duck Trail.

Canine compatibility: Dogs not permitted, not even in the car

Trail contact: Day hikes: Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, 8231 Beach Rd., Chincoteague; (757) 336-6122; www.fws.gov/refuge/chincoteague. Backcountry: Assateague Island National Seashore, Toms Cove Visitor Center (Virginia Ranger Station); (757) 336-6577; www.nps.gov/asis

Schedule: Chincoteague NWR is open daily, 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. May through Sept; 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. Nov through Mar; 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. Apr and Oct. The Toms Cove Visitor Center (National Seashore) is open 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. Portions of beaches and trails may be closed for bird nesting in spring and summer and for hunting in Oct, Dec, and Jan. Be sure to call ahead for details.

Fees/permits: Entrance fee per vehicle; bicycles and pedestrians free. Backcountry permit required; register at the Toms Cove Visitor Center. Backpackers must depart at least 4 hours before sunset, with enough daylight to hike 12 miles to the State Line or Pope Bay backcountry campsites in Maryland. Visit www.nps.gov/asis for camping rules and regulations.

Facilities/features: Restrooms, educational and visitor centers, lifeguarded beach, kayak launch on the Virginia end of the island. Primitive camping is allowed across the Maryland border only; there are portable toilets, but all freshwater must be carried in.

NatGeo TOPO! map: Chincoteague East

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Delmarva Peninsula

Other maps: Refuge and Park Service maps available at visitor center and online.

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From the new Chincoteague Bridge (VA 175): For the Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop, stay straight to go on Maddox Boulevard (VA 2113). Drive 1.2 miles to a traffic circle and follow Maddox Boulevard through the circle. In 1.4 miles, reach the refuge entrance gate, where Maddox Boulevard becomes Beach Road. Enter the refuge and in 0.3 mile, turn left into the parking area for the Herbert H. Bateman Educational Center at 8231 Beach Road. This ecofriendly building serves as the visitor center, with nature exhibits inside. For the Beachfront Backpack, after entering the refuge, continue past the educational center and enter the Assateague Island National Seashore. In 1.5 miles, reach the Toms Cove Visitor Center on the right to obtain a backcountry permit and parking tag. Visitor center GPS: N37 54.544’ / W75 21.337’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 63, A5.

From the new Chincoteague Bridge (VA 175): For the Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop, stay straight to go on Maddox Boulevard (VA 2113). Drive 1.2 miles to a traffic circle and follow Maddox Boulevard through the circle. In 1.4 miles, reach the refuge entrance gate, where Maddox Boulevard becomes Beach Road. Enter the refuge and in 0.3 mile, turn left into the parking area for the Herbert H. Bateman Educational Center at 8231 Beach Road. This ecofriendly building serves as the visitor center, with nature exhibits inside. For the Beachfront Backpack, after entering the refuge, continue past the educational center and enter the Assateague Island National Seashore. In 1.5 miles, reach the Toms Cove Visitor Center on the right to obtain a backcountry permit and parking tag. Visitor center GPS: N37 54.544’ / W75 21.337’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 63, A5.

THE HIKE

Screams and cries rise off the oceanfront as hungry gulls and terns scavenge for food along the surf. Beyond Assateague Island’s low sand and inland pine, snow geese float restlessly in a freshwater pool. Suddenly, on some silent, unseen signal, a single goose, then two, three—then the entire flock rises in flight. Their whonk-whonk joins with cries of shorebirds in a resounding cacophony.

An explosion of snow geese off the water draws the birder’s eyes skyward. Here, a broad-winged raptor swoops high above the pond. Its brown wings tilt slightly left, then right in a jittery act of balance. The telltale white head and yellow, hooked bill soon come into focus. This bald eagle, its search for a meal frustrated, soars out of sight behind crowns of loblolly pine.

This winter struggle between prey and predator will end when snow geese fly north in spring. Closer to the ocean, a different life struggle begins in spring when piping plover descend upon Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge on the southern tip of Assateague Island. After a brief courtship, breeding pairs build a nest in the sand. Up to four eggs will hatch within a month of being laid. For 5 critical days, the young chick’s life consists of dodging predators and finding enough food to survive. Days turn to weeks, and the handful of chicks that survive face new dangers. Camouflage, the tiny, sand-colored plover’s best defense, leads to unintended consequences: Humans inadvertently step on nests. Off-road vehicles run them over. Gulls harass adult plovers and carry away chicks. Other predators, raccoons and foxes among them, raid nests. Storms send tidal surges crashing over protective dunes—violent weather has destroyed entire nesting seasons at Chincoteague.

Animals fend for themselves on a daily basis in a never-ending search for an advantage—and a meal. Humans represent an interference in this delicate balance. The side of the scale on which we place our weight makes all the difference. In the case of the Delmarva fox squirrel, farming and homes had, by 1900, destroyed habitat in all but a tiny spot in Maryland. The balance tipped in the squirrel’s favor in 1945, however, when Maryland set aside land for its protection. In 1971 it became illegal to hunt the large fox squirrel, which can weigh up to 3 pounds and measure 30 inches in length. On reserves in Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware, squirrel populations increased. From a population of thirty squirrels in 1970, Chincoteague now keeps its numbers around 350, shipping out squirrels to other suitable habitats if their numbers exceed this level.

Human intervention, often the cause of ailing animal populations, is just as often the cure. When plover chicks hatch in late May, refuge staff begin a 16- to 18-hour vigil over nesting sites. Nesting areas are signed and roped off, and occasionally beach roads are closed to vehicular traffic. In 2007 eighty plover chicks fledged, or were able to fly, on refuge islands, according to a shorebird productivity report. Assateague Island, along with neighboring barrier islands, accounts for the majority of the piping plover’s breeding population in Virginia.

HEADS UP

Storms routinely over-wash the beach parking areas as Assateague Island experiences erosion, sea level rise, and a westward migration. Plans are to relocate parking lots 1.5 miles farther north, and facilities farther away from the beach.

The Chincoteague refuge also played an instrumental role in the recovery of breeding peregrine falcons in Virginia. By the 1960s breeding peregrines had disappeared from the state, suffering from a fate similar to the bald eagles’—contamination from the pesticide DDT. Weakened eggshells broke, and chicks hatched prematurely. DDT was banned in 1972. In the late 1970s scientists began releasing pairs of peregrines in Virginia, both in coastal and mountain regions. In 1982 they hit gold when a pair of peregrine falcons was found nesting on Assateague Island, the first documented breeding pair in the state in nearly a half a century. As of 2010 Virginia supports twenty-three known breeding pairs of peregrine falcons, nearly all within the state’s portion of the Eastern Shore. A delisting of the peregrine from an endangered species to a threatened species reflects national success in reintroducing breeding populations.

And yet even in a managed environment, disaster strikes. When several storms inundated the maritime forest of lower Assateague Island—which encompasses the whole of the Chincoteague refuge—volumes of saltwater weakened the resident loblolly pines. The stress caused by a lack of freshwater made the pines susceptible to the southern pine beetle. Recovery from this trauma can be seen today along the Wildlife Loop Trail—where amid low shrubs and grass, pine saplings have made a vigorous comeback.

KID APPEAL

With rare exceptions, everyone wants to catch a glimpse of the famous Chincoteague wild ponies, which reside in the refuge and national seashore. The 1.6-mile Woodland Trail leads through a pine forest to an overlook where pony sightings are common. The new Bivalve Trail is a 0.2-mile spur off the Woodland Trail that leads to the shores of Toms Cove with a view of the old Assateague life-saving station.

For years, protection of Assateague Island extended to correcting nature itself. After every major storm, the Park Service rebuilt dunes with the goal of keeping an ocean ecology from slipping away. Littoral drift, the term for a shift in barrier islands westward, moves Assateague, on average, 30 feet every decade. But not everything needs protecting. Park managers have decided against rebuilding dunes and are now questioning the wisdom of building (and rebuilding) parking lots near the beach. Whatever conditions a storm leaves the barrier island in, staff are now inclined not to tamper with it. Humans, and not the environment, will adapt to conditions. Briefly, balance tips back to Mother Nature.

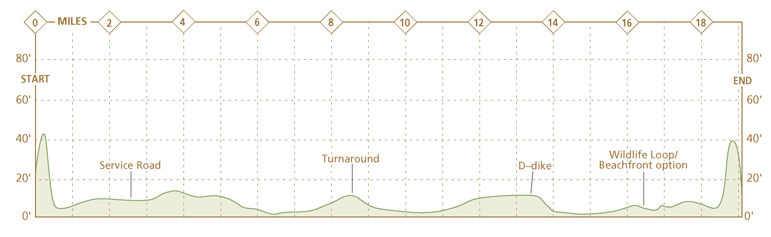

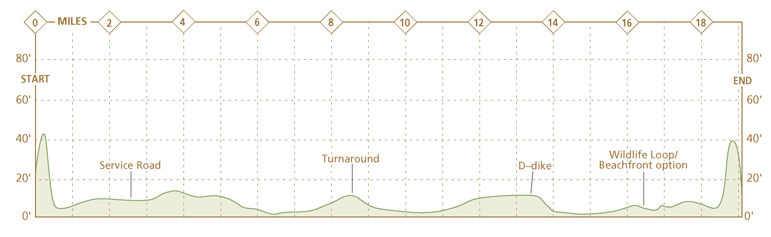

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

WILDLIFE POND/BEACHFRONT LOOP

0.0Start from the parking lot for the Herbert H. Bateman Educational Center. Opposite the visitor center, a boardwalk trail leads away through a pine forest.

0.3Merge onto the paved Wildlife Loop road, which is open to vehicles from 3 p.m. to dusk, and continue straight. Views of Snow Goose Pool, a freshwater impoundment, open up on the left.

0.7Continue straight on the Wildlife Loop road past the Black Duck Trail, which exits to the right and leads 0.5 mile to paved Beach Road.

1.4Continue straight, past Swan Cove Trail, which exits to the right and is part of the return leg of this loop.

2.5Cross Snow Goose Pool on a dike and turn right onto a gated dirt road, which is closed to public vehicle traffic except between Memorial Day and Labor Day, when sightseeing trams operate. Option: To return to the educational center, turn left at this T junction and follow the paved Wildlife Loop Road.

3.1Continue straight on the gravel road past C-Dike. Note: This earthen embankment is closed and may not be used to access the beach.

3.6Turn right onto D-Dike and hike 0.3 mile to the oceanfront.

3.9Emerge from the dunes onto the beach. Turn right and head south along the beachfront.

5.5Turn right and walk through the beach dunes onto Swan Cove Trail. Note: This trail may be closed during periods of high rainfall.

6.0Swan Cove Trail ends at Wildlife Loop. Bear left to return to the educational center.

7.5Arrive back at the Herbert H. Bateman Educational Center parking area.

BEACHFRONT BACKPACK

0.0Start from the Toms Cove Visitor Center, where you must obtain a backcountry permit and inquire where to park overnight. Head to the beachfront, turn left, and walk north. Note: To eliminate a couple of miles walking in the sand, ask about parking across from the lighthouse and hiking on the Service Road to the beach.

2.9Pass a dune crossover to D-Dyke on the left. Continue straight.

9.4Pass Old Fields crossover, a route leading left through the dunes to an interior service road. Continue straight.

11.0Cross the Maryland state line and enter Assateague Island National Seashore. Continue straight.

12.5A tent sign in the dunes to the left indicates State Line campsites, primitive sites with no running water, and chemical toilets. Camping is permitted amid dunes only. Turn around and return to the Toms Cove Visitors Center. Note: If State Line camp is booked, Pope Bay on the bayside of Maryland’s Assateague Island is 0.5 mile north.

25.0Hike ends at Toms Cove Visitor Center.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Chincoteague Chamber of Commerce, (757) 336-6161, www.chincoteaguechamber.com

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

Annual Pony Swim and Penning, last week in July, Chincoteague, (757) 336-6161. An event of national renown, wild Chincoteague ponies are driven off the refuge across a small water passage and penned on Chincoteague Island for auction.

International Migratory Bird Celebration in spring, National Wildlife Refuge Week in Oct, Waterfowl Week in Nov, Christmas Bird Count, all at Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, (757) 336-6122

LODGING

The resort town of Chincoteague has a wide array of lodgings, from motels and B&Bs to rental homes. Visit www.chincoteaguechamber.com for listings.

There are several commercial campgrounds in Chincoteague, but backcountry camping is allowed only at Assateague National Seashore in Maryland.

RESTAURANTS

Nearly thirty Chincoteague restaurants serve up fare ranging from seafood to homemade ice cream to the standard burger and fries.

TOURS

Refuge staff lead interpretive programs. Call (757) 336-6122 for information.

ORGANIZATIONS

Assateague Island Alliance, www.assateagueislandalliance.org

OTHER RESOURCES

Eastern Shore of Virginia Tourism, (757) 331-1660, www.esvatourism.org

From the new Chincoteague Bridge (VA 175): For the Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop, stay straight to go on Maddox Boulevard (VA 2113). Drive 1.2 miles to a traffic circle and follow Maddox Boulevard through the circle. In 1.4 miles, reach the refuge entrance gate, where Maddox Boulevard becomes Beach Road. Enter the refuge and in 0.3 mile, turn left into the parking area for the Herbert H. Bateman Educational Center at 8231 Beach Road. This ecofriendly building serves as the visitor center, with nature exhibits inside. For the Beachfront Backpack, after entering the refuge, continue past the educational center and enter the Assateague Island National Seashore. In 1.5 miles, reach the Toms Cove Visitor Center on the right to obtain a backcountry permit and parking tag. Visitor center GPS: N37 54.544’ / W75 21.337’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 63, A5.

From the new Chincoteague Bridge (VA 175): For the Wildlife Pond/Beachfront Loop, stay straight to go on Maddox Boulevard (VA 2113). Drive 1.2 miles to a traffic circle and follow Maddox Boulevard through the circle. In 1.4 miles, reach the refuge entrance gate, where Maddox Boulevard becomes Beach Road. Enter the refuge and in 0.3 mile, turn left into the parking area for the Herbert H. Bateman Educational Center at 8231 Beach Road. This ecofriendly building serves as the visitor center, with nature exhibits inside. For the Beachfront Backpack, after entering the refuge, continue past the educational center and enter the Assateague Island National Seashore. In 1.5 miles, reach the Toms Cove Visitor Center on the right to obtain a backcountry permit and parking tag. Visitor center GPS: N37 54.544’ / W75 21.337’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 63, A5.