4. YORK RIVER STATE PARK

WHY GO?

The worm-eating warbler, common to Virginia’s Blue Ridge province, is also found in the coastal environment of York River State Park. After walking through the park’s forests, thick with mountain laurel and holly, shaded by chestnut oaks and American beech, hikers will agree with the songbird: This park feels a lot like Virginia’s mountain regions. Most paths here lead through mature hardwood forests to overlooks onto the York River. Land underfoot holds evidence–pottery shards, arrowheads–of settlement dating from tens of thousands of years ago. Perhaps the park’s most interesting story is still being recorded–that of the Taskinas Creek Estuary, a vital marsh and hardwood swamp monitored by scientists as a gauge of the Chesapeake Bay’s health.

THE RUNDOWN

Start: Park contact and fee station

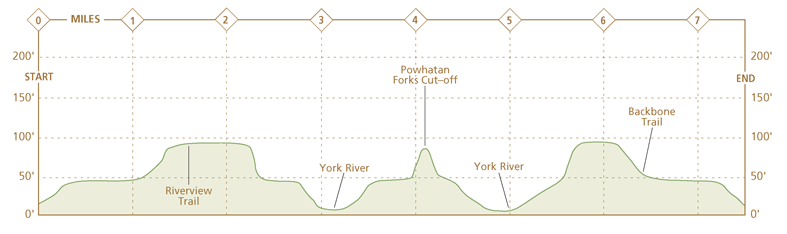

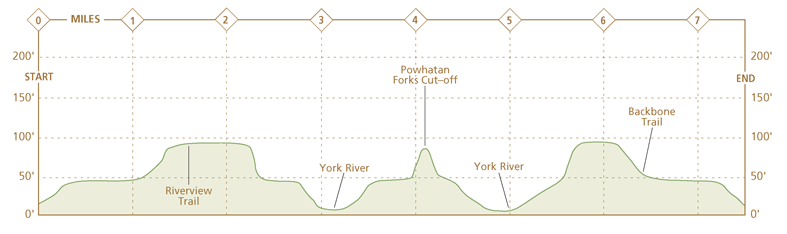

Distance: 7.7-mile loop

Hiking time: 1-4 hours

Difficulty: Easy due to flat terrain, well-marked trails, and options for shorter hikes

Trail surface: Wooded paths, boardwalks, and gravel and dirt roads lead through marsh, fields, hardwood swamps, and upland forests.

Land status: State park

Nearest town: Williamsburg, VA

Other trail users: Cyclists and equestrians

Accessibility: Paved paths along native plant arboretum to canoe dock, 0.5-mile path around day-use area, and 0.75-mile ADA backwoods trail

Canine compatibility: Leashed dogs permitted (leashes no longer than 6 feet)

Trail contact: York River State Park, 5526 Riverview Rd., Williamsburg; (757) 566-3036; dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/york-river

Schedule: Open daily year-round, 8 a.m. to dusk. The visitor center is open year-round, but the visitor center office operates on a limited schedule from Nov to Mar.

Fees/permits: Per-vehicle entrance fee

Facilities/features: Visitor center, concessions, gift shop, ADA restrooms, picnic shelters, boat launch, and kayak and canoe rentals on a 7-acre pond and on Taskinas Creek

NatGeo TOPO! map: Gressitt

Other maps: A Trail Guide/Map is available at the park and downloadable on its website.

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From I-64, take the Croaker exit 231B and go 1.2 miles north on Croaker Road/VA 607. Turn right onto VA 606–also called Riverview Road–and drive 1.7 miles to VA 696. Turn left onto VA 696 (York River Park Road). The fee station is in 2 miles. Parking lots for the visitor center, picnic area, and trails are just beyond the fee station. GPS: N37 24.718′ / W76 42.847′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 50, A1.

From I-64, take the Croaker exit 231B and go 1.2 miles north on Croaker Road/VA 607. Turn right onto VA 606–also called Riverview Road–and drive 1.7 miles to VA 696. Turn left onto VA 696 (York River Park Road). The fee station is in 2 miles. Parking lots for the visitor center, picnic area, and trails are just beyond the fee station. GPS: N37 24.718′ / W76 42.847′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 50, A1.

THE HIKE

Offshore of Taskinas Creek Trail, salt marsh cordgrass sways with a stiff breeze. On the creek’s muddy flats, spotted sandpipers and black-bellied plovers dart in earnest pursuit of food. A cluster of fiddler crabs scuttle for shelter. As you climb away from the creek on a trail beneath oak and beech trees, a great blue heron, startled, lumbers toward open water, letting loose a gaaak as a parting shot.

How much, you might wonder, can these scenes differ from those of 300 years ago? The Native Americans of eastern Virginia were a riverine people; their lives revolved around what the rivers provided. Men hunted meadow and wood for white-tailed deer, turkey, and other prey, but the water provided all things necessary for life: food; fertile soil; shells for ornaments, tools, and trading; reeds for mats and baskets; and even transportation. At low tide, women foraged in freshwater marsh for arrow arum, whose root, tuckahoe, is edible when boiled. Thick-stemmed saltwort, pickled or preserved, made a tasty delicacy.

English settlers called it a “hand-to-mouth” existence, and yet their survival, too, depended on it. On a monthly—sometimes biweekly—basis, Native Americans sent gifts of food to the James Island fort in 1607—8, sustaining settlers during spring “starving times,” when the previous fall’s harvest had run out and new forest growth made hunting more difficult. When English farmers spread beyond fort walls onto the James/York River Peninsula, they found why the Native Americans could afford generosity: Chiskiack Indians planted maize, beans, and squash among burned tree stumps, remnants of field clearing. It was a high-yield, if not terribly efficient, farming system.

York River State Park’s Powhatan Forks Trail crosses high peninsula meadows, then enters the shade of hardwood forest. A person who has spent time in Virginia’s mountain woods may sense something familiar. The trees—chestnut oak, American beech, green ash—and a forest understory of mountain laurel, holly, and berry-producing shrubs thrive here thanks to soil conditions normally found in western Virginia. York River State Park soil contains marl, a limestone-heavy clay similar to soils of the Shenandoah Valley. Elsewhere in the park, the Yorktown rock formation sinks as deep as 150 feet or more underfoot. This is a calcium-rich soil, thick with deposits of ancient seashell and sand. Prehistoric seas washed over Virginia’s coastal region several times. Erosion along the York River constantly churns up fossils pointing to past aquatic life. Unearthing 5-million-year-old shells and whalebones is not an uncommon occurrence here.

Where the north branch of Powhatan Forks Trail drops into a marshy area, an expansive view of the river opens up. This approach is much gentler than the Riverview Trail’s abrupt ending on high river bluffs a half-mile downstream, yet both permit an unobstructed view of Purtan Bay on the opposite shore. Captain John Smith, hoping to save a struggling colony, took in a similar vista in the fall of 1608. (Today, homes dot that far shoreline and recreation boats bob in the water.) In Captain Smith’s time, Purtan Bay was one home of Powhatan, chief of the eastern Native American empire that bore his name. His tribe, the Werowocomoco, built huts along the shallow bay and its three tributaries and used fragile bridges strung across tidal flats as links with each other.

In what must have been an embarrassing moment for the adventurous John Smith, he and a party of men crossed the York River to meet Powhatan, but landed in the wrong spot. Some men disembarked and tried crossing a stream by way of a bridge made of forked stakes and planks. It defeated the heavily clad men, and the Werowocomoco ferried them, a few at a time, across the creek. Later, after negotiating for corn, Smith and company tried returning to their ship, but his canoe ran aground on a mudflat. Powhatan’s men trudged out to retrieve them; Smith asked instead for “some wood, fire, and mats to cover me.” He spent the night thusly, waiting for the tide to return and float his boat off its hang-up.

Despite initial feebleness, the expanding colony soon had Powhatan’s empire in retreat. Nathaniel Bacon Jr., a settler, led a group of armed, discontented landowners against the Native Americans in the summer of 1676. Miffed by the colonial governor William Berkeley’s inability to keep Indian raiders in check, Bacon’s men soon hounded the governor into hiding. Given virtually free rein, Bacon used outposts throughout the Tidewater to launch attacks. As a result, travelers today will see his name attached to innumerable homes, old forts, back roads, and “hideaways” throughout the region. York River State Park is no different. Near the park stands the Stonehouse site, a 17th-century military outpost during Bacon’s Rebellion, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Occoneechee tribe fell in May 1676, and the Pamunkey fell in August of that same year.

Bacon died of natural causes in October 1676 and Berkeley regained control of the Virginia colony. In February 1677, English settlers and Native Americans struck the Treaty of Middle Plantation. Besides war reparations—prisoners, land, weapons, tools—the treaty made remnants of a once-powerful Indian empire formal subjects to the king of England. It called for an annual tribute of three arrows and twenty beaver pelts in exchange for reservation land near West Point, Virginia. More than 300 years later, the Treaty of Middle Plantation remains in force. Each autumn, Mattaponi (matta-PO-ni) and Pamunkey Indians trek to the governor’s mansion to pay their rent for reservation land—a deer strung on a pole, with tribesmen dressed in full regalia supporting either end of the stick.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start from the park contact and fee station. Follow a paved path alongside the park entrance road. In a few hundred feet, this paved path becomes a gravel-lined two-track path as it enters woods. There is a yellow sign on the right for the Backbone Trail. Note: Park trail maps identify this stretch as combined Backbone Trail/Woodstock Pond Trail.

0.16Pass the Beaver Trail on the left. Option: Beaver Trail is a 0.6-mile alternative for circling Woodstock Pond. It ends near the York River at a junction with Woodstock Pond Trail. Use Beaver Trail to complete a shorter loop around the pond that will return you to the park visitor center.

0.4At the junction of Woodstock Pond Trail, turn right on Backbone Trail, a hard-packed dirt road that runs 1.4 miles to the park’s south boundary. Both cyclists and hikers use this trail. The Meh-Te-Kos bridle path (for horses) intersects it at numerous points. Following Woodstock Pond Trail left leads to return to the visitor center in 0.8 mile.

1.2Walk past the Pamunkey Trail, which branches left off Backbone Trail. Note: At this intersection, a power line cuts across Backbone Trail. Stick to the roadway bearing right.

1.4Continue straight on Backbone Trail past a junction on the left for Powhatan Forks Trail.

1.6Arrive at junction with Riverview and White-Tail Trails on the left. Veer left onto White-Tail Trail. (There’s a picnic table here.)

1.65Turn right onto Dogwood Lane Trail, a rutted narrow dirt road flanked by mountain laurel on the high-banked dirt roadsides.

2.0Stay on Dogwood Lane Trail as a service road veers right. From here, Dogwood continues as a singletrack path through heavy woods flush with turkeys, pheasants, and deer.

2.4Bear right onto White-Tail Trail.

2.8White-Tail Trail ends in a large clearing that has limited winter and spring views of the York River. Turn around and retrace your steps along White-Tail Trail.

3.2Continue straight on White-Tail Trail past a junction with Dogwood Trail on the left.

3.5White-Tail Trail junctions with Riverview and Backbone Trails. Veer right onto Riverview Trail, which is a wide, sandy two-track woods path.

3.7Approach an open clearing and a junction with Powhatan Forks Trail. Continue on Riverview Trail, which bears right into the woods. A trail sign here notes that it is 1.27 miles to the end of Riverview at the York River. Note: The clearing is a former archaeological dig site.

3.9Bear right onto Powhatan Forks Trail at a Y-shaped junction. The trail here is a mowed path.

4.1Powhatan Forks Trail splits left and right. Bear left on the North Branch Powhatan Forks Trail. The trail gradually descends to the York River through a forest lush with mountain laurel and American holly trees.

4.7A wide spot on the North Branch Powhatan Forks Trail features views of the York River and a wood bench for resting. Follow the trail as it descends off the hillside to a boardwalk across a river marsh.

4.9On the opposite side of the boardwalk, climb the stream bank to another overview of the York River and turn left onto the Majestic Oak Trail.

5.5Bear right on Spurr Trail.

5.7Turn left on Pamunkey Trail.

5.8Turn right onto Backbone Trail.

6.7Backbone Trail bends left to return to the park contact and fee station. Continue straight on Woodstock Pond Trail.

7.5Ascend on Woodstock Pond Trail and follow a path as it bends left through the field and past the visitor center.

7.7Arrive back at the state park contact and fee station.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Williamsburg Area Destination Marketing Committee, (888) 882-4156, www.visitwilliamsburg.com

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

Estuaries Day, late Aug. Displays, demonstrations, boat tours, and other programs centered around Taskinas Creek. Contact the park for specific dates and times.

Ghost Trail Hayrides are held in the park in the fall.

TOURS

Sunset canoe trips and stargazing are offered in the park May through Oct.

ORGANIZATIONS

Friends of York River State Park, Williamsburg, (757) 566-3036, Facebook group

From I-64, take the Croaker exit 231B and go 1.2 miles north on Croaker Road/VA 607. Turn right onto VA 606–also called Riverview Road–and drive 1.7 miles to VA 696. Turn left onto VA 696 (York River Park Road). The fee station is in 2 miles. Parking lots for the visitor center, picnic area, and trails are just beyond the fee station. GPS: N37 24.718′ / W76 42.847′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 50, A1.

From I-64, take the Croaker exit 231B and go 1.2 miles north on Croaker Road/VA 607. Turn right onto VA 606–also called Riverview Road–and drive 1.7 miles to VA 696. Turn left onto VA 696 (York River Park Road). The fee station is in 2 miles. Parking lots for the visitor center, picnic area, and trails are just beyond the fee station. GPS: N37 24.718′ / W76 42.847′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 50, A1.