5. BELLE ISLE STATE PARK

WHY GO?

Since colonial times, farmers have tilled the fields of Belle Isle; parts of this state park are farmed even today. Bird-watchers, hikers, horseback riders, and cyclists in the mood for wide-open spaces find this an ideal destination. Trails trace cornfields, cross tidal marshes, and wind through pine and hardwood filter strips–ribbons of woodland that separate fields from sensitive wetlands. Well-marked and easy to follow, trails feature interpretive boards explaining Chesapeake Bay ecology. Depending on the season, there’s a better-than-average chance of spotting a bald eagle or two, flocks of wintering tundra swans, and in summer, maybe a dolphin cruising the wide Rappahannock.

THE RUNDOWN

Start: Mud Creek boat launch parking lot

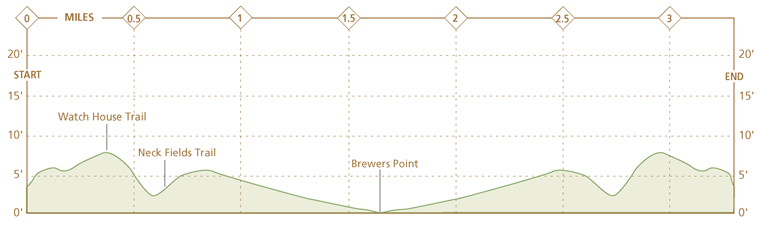

Distance: 3.3 miles out and back

Hiking time: About 1 hour

Difficulty: Easy due to flat terrain, short distance, and well-marked trails

Trail surface: Gravel roads and dirt woodland paths through farmland, marsh, and swamp-fringe forest leading to river views

Land status: State park

Nearest town: Lancaster, VA

Other trail users: Cyclists and equestrians

Accessibility: Many of the park’s trails are gravel, so wheelchairs may be able to use them with assistance. The 1,000-foot boardwalk, observation deck, and fishing pier are accessible.

Canine compatibility: Leashed dogs permitted (leashes no longer than 6 feet)

Trail contact: Belle Isle State Park, 1632 Belle Isle Rd., Lancaster; (804) 462-5030; www.dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/belle-isle. For camping and guesthouse reservations, call (800) 933-PARK or visit www.reserveamerica.com.

Schedule: Open year-round, dawn to dusk. Full-service campground open first Fri in Mar to the first Mon in Dec. Year-round primitive camping. The Bel Air House and Bel Air Guesthouse can be rented year-round.

Fees/permits: Parking fee

Facilities/features: Boat ramp, canoe/kayak launch, and rentals for motorboats, canoes, kayaks, and bikes. Campground, two guesthouses.

NatGeo TOPO! map: Lively

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Delmarva Peninsula

Other maps: A Trail Guide/Map is available at the park and downloadable on its website.

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From Lancaster Courthouse, take VA 3 west for 3 miles and turn left onto White Chapel Road/VA 201 in the village of Lively. Drive 3.2 miles and turn right onto River Road/VA 354 at St. Mary’s White Chapel. Head west for 3.2 miles and turn left onto Belle Isle Road/VA 683. The park office is 2 miles down the road. Turn right to the cartop launch parking area. The Mud Creek Trail starts on the wood’s edge, behind a trail board. GPS: N37 46.931′ / W76 36.203′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 60, B2.

From Lancaster Courthouse, take VA 3 west for 3 miles and turn left onto White Chapel Road/VA 201 in the village of Lively. Drive 3.2 miles and turn right onto River Road/VA 354 at St. Mary’s White Chapel. Head west for 3.2 miles and turn left onto Belle Isle Road/VA 683. The park office is 2 miles down the road. Turn right to the cartop launch parking area. The Mud Creek Trail starts on the wood’s edge, behind a trail board. GPS: N37 46.931′ / W76 36.203′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 60, B2.

THE HIKE

On a cold, moonless winter night, a boat circles in the black mist rising off the Rappahannock River. A bushel basket floats upside down in the water and underneath it, a light flickers. The pilot deftly navigates while two shadows operate a dredge. There’s a sureness in their movements, though hardly a word passes between them.

Still, it’s hard to stay hidden. Wind carries sounds ashore. A spotlight blasts through the fog, freezing the crew in its bright gaze. Momentarily stunned, the men snap to attention. Harsh words drift out of the darkness: “Cut your engines.” Instead, the pilot revs his motor and swings toward deep water. Noise and wind drown out the snap, snap, snap of rifle shots. Nighttime swallows the poachers and their stash of oysters.

On land, the spotlight refocuses on the abandoned bushel basket; the wide beam also illuminates tall, skinny sticks marking an oyster bed. The light stays trained on this spot until dawn. A watchman, awake and alert, sits in a house on shore, rifle across his knee, ready for the next raider.

Starting after the Civil War, turning violent first in the 1880s and 1890s, and again in the 1940s and 1950s, the oyster wars of the Chesapeake Bay pitted Virginia and Maryland watermen against each other, vying for what was then the Chesapeake Bay’s most sought-after resource. Along the Northern Neck and Eastern Shore, in alleys and saloons of tough water towns such as Crisfield, Maryland, and Colonial Beach, Virginia, Marylanders fought Virginians over the oyster. In the shallow waters of the Eastern Shore sounds, tongers— watermen who collected oysters using long-handled tongs—resisted dredgers, whose large scoops raped the bay bottom, and everyone, it seemed, fought the marine police, whose vigilance ebbed and flowed like the ocean tides—strict and trigger happy one moment, indifferent the next.

Belle Isle State Park, in Lancaster County on Virginia’s Northern Neck, was—if not a hot spot in this war—a lukewarm spot, at least. On this spit of land, Thomas Powell staked out the original 500 acres for a farm and plantation in 1650. The period marked a population boom of sorts for the Northern Neck. In the 1650s settlers were gobbling up land on this northernmost of Virginia’s peninsulas. Ancestors of three presidents— George Washington, James Monroe, and James Madison—settled farther up this strip during this period. Farms soon became plantations, modest homes turned into manor houses, and Belle Isle thrived as a tobacco-producing estate, with cotton, flax, wheat, and corn grown as well.

Yet Belle Isle’s envious perch on the Rappahannock River could not be ignored. Native Americans called the Rappahannock the “quick-rising” river. Narrow and shallow, its brackish mix of saltwater and freshwater extends upriver for miles, making it ideal for growing oysters—especially in tidal flats at the mouth of Mulberry and Deep Creeks, which create Belle Isle’s distinctive landform.

Watermen jealously guarded these beds. For good reason, too. By one estimate, as many as 170 poachers operated in the Chesapeake Bay in the 1940s and 1950s. Worsening matters, after decades of overharvesting, oyster production was in decline. At a peak in 1880, watermen caught 125 million pounds of oysters. By 1958—59, a mere 4 million bushels were harvested. (There was a temporary rebound in the late 1970s, when the harvest jumped to 25 million pounds, but numbers dropped to 138,000 pounds by 1998.) Scarcity drove up price; suppliers paid $3.25 a bushel in 1958–59 (up from 60 cents a bushel in the 1880 heyday).

As overharvesting depleted natural oyster beds, seed beds like those off Belle Isle became a tempting target. To guard against poachers, watermen built shacks on elevated platforms overlooking tidal flats. Scattered along riverbanks and sounds of the Chesapeake Bay, the buildings-on-stilts formed a ragtag line of defense, akin to outposts on a distant frontier.

Across from Belle Isle State Park’s offices, a wide, dirt and gravel trail passes by a field of corn to your right. Fields soon drop away and the trail enters a narrow strip of pine and hardwoods. Fringe forests like these act as a barrier between field runoff and fragile wetlands. Continuing on, the path crosses a neck of land bounded by tidal marshes. On your left you’ll see where waterfowl flock to Porpoise Creek, and where its marsh grass segues into the deeper, blue waters of Deep Creek, look for wintering tundra swans in spectacular white groups numbering from ten to one hundred. (They arrive in December and leave in March.) Although a bit removed from the Atlantic Flyway—the north-south route for migrating birds that traces Virginia’s Eastern Shore—migratory birds still flock to Belle Isle.

Finally, the trail meets the lapping shores of the Rappahannock River. Look closely around you for clues to a chapter in this plantation-turned-park’s history. Overgrown with grass, decaying wood pilings and riprap mark the site of an old watch house. You’ve hiked only a short distance, but you’ve witnessed at least 350 years of history.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start from the Mud Creek boat launch parking lot. Take Mud Creek Trail southeast, back toward the park office.

0.1Mud Creek Trail passes between two thick-trunk oaks whose branches, high overhead, entwine to create a natural arbor.

0.2Mud Creek Trail turns sharply left and emerges from the woods, then bears right to follow the edge of a cornfield. A red barn is visible across the field. As you emerge into the open, look for the round, spindly fruit of the sweet gum.

0.3Mud Creek Trail ends at a T intersection with Watch House Trail, a wide gravel and dirt road that heads left and right. Turn right. Note: Turning left onto Watch House Trail will lead you to a picnic area and the park office, as well as a trailhead for horseback riders.

0.6Arrive at a T intersection with Neck Fields Trail, another wide dirt and gravel road. Turn right onto Neck Fields Trail and continue your hike to Brewers Point.

1.5The trail detours around a small pond hidden behind a tangle of small shrubs, vines, and trees. Peek through for a sighting of merganser and canvasback, two types of ducks that call Belle Isle home.

1.65The trail ends at Brewers Point on the Rappahannock River. There is a picnic table here. Retrace your steps back to the boat launch parking lot.

3.3Hike ends at the parking lot.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

The Northern Neck Tourism Council, Warsaw, (804) 333-1919, www.northernneck.org

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

Music by the River concerts are held in the park May through Aug,, and Haunted Evening programs take place in Oct.

Stratford Hall Plantation, Stratford, (804) 493-8038, www.stratfordhall.org. This is Robert E. Lee’s ancestral home.

St. Mary’s Whitechapel, Lancaster, (804) 462-5908, www.stmaryswhitechapel.org. George Washington’s mother, Mary Ball Washington, was from Lancaster County, and many of her ancestors are buried in the churchyard.

LODGING

Lodging is available within the park at The Bel Air Overnight Area, consisting of the Bel Air House and Guesthouse and a full-service campground. For reservations, call (800) 933-PARK or visit www.reserveamerica.com.

ORGANIZATIONS

Friends of Belle Isle State Park, www.virginiaparks.org/friends-bi

From Lancaster Courthouse, take VA 3 west for 3 miles and turn left onto White Chapel Road/VA 201 in the village of Lively. Drive 3.2 miles and turn right onto River Road/VA 354 at St. Mary’s White Chapel. Head west for 3.2 miles and turn left onto Belle Isle Road/VA 683. The park office is 2 miles down the road. Turn right to the cartop launch parking area. The Mud Creek Trail starts on the wood’s edge, behind a trail board. GPS: N37 46.931′ / W76 36.203′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 60, B2.

From Lancaster Courthouse, take VA 3 west for 3 miles and turn left onto White Chapel Road/VA 201 in the village of Lively. Drive 3.2 miles and turn right onto River Road/VA 354 at St. Mary’s White Chapel. Head west for 3.2 miles and turn left onto Belle Isle Road/VA 683. The park office is 2 miles down the road. Turn right to the cartop launch parking area. The Mud Creek Trail starts on the wood’s edge, behind a trail board. GPS: N37 46.931′ / W76 36.203′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 60, B2.