19. NORTH FORK MOORMANS RIVER

WHY GO?

North Fork Moormans River runs a modest path down the foothills of the Blue Ridge along Shenandoah National Park’s east boundary. Fly fishers work the stocked waters. Hikers push upstream toward the waterfalls on picturesque mountain streams that feed the North Fork. Beyond the most popular day hikes lies rugged Shenandoah backcountry. From Sugar Hollow Reservoir deep into the park, the landscape shows scars of a 1995 flood that swelled the river and tributaries with water, rocks, trees, and mud. This is not only a great day hike, but also a firsthand account of earth-shaping events, and the process of recovery that follows.

THE RUNDOWN

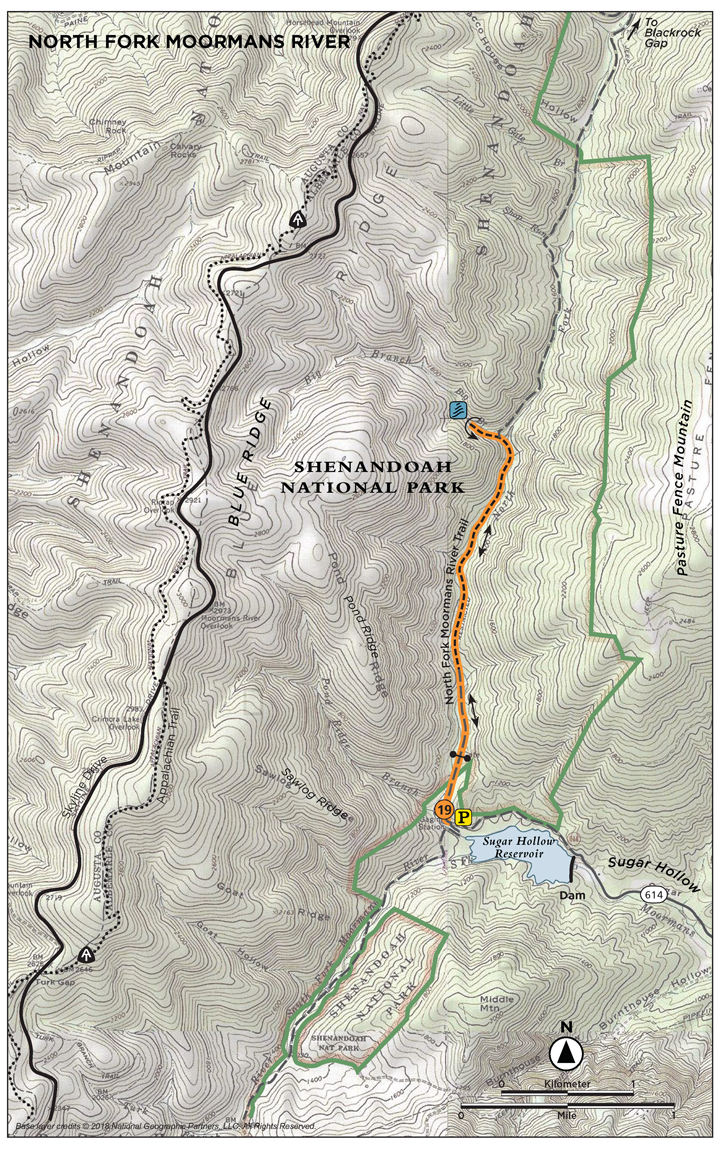

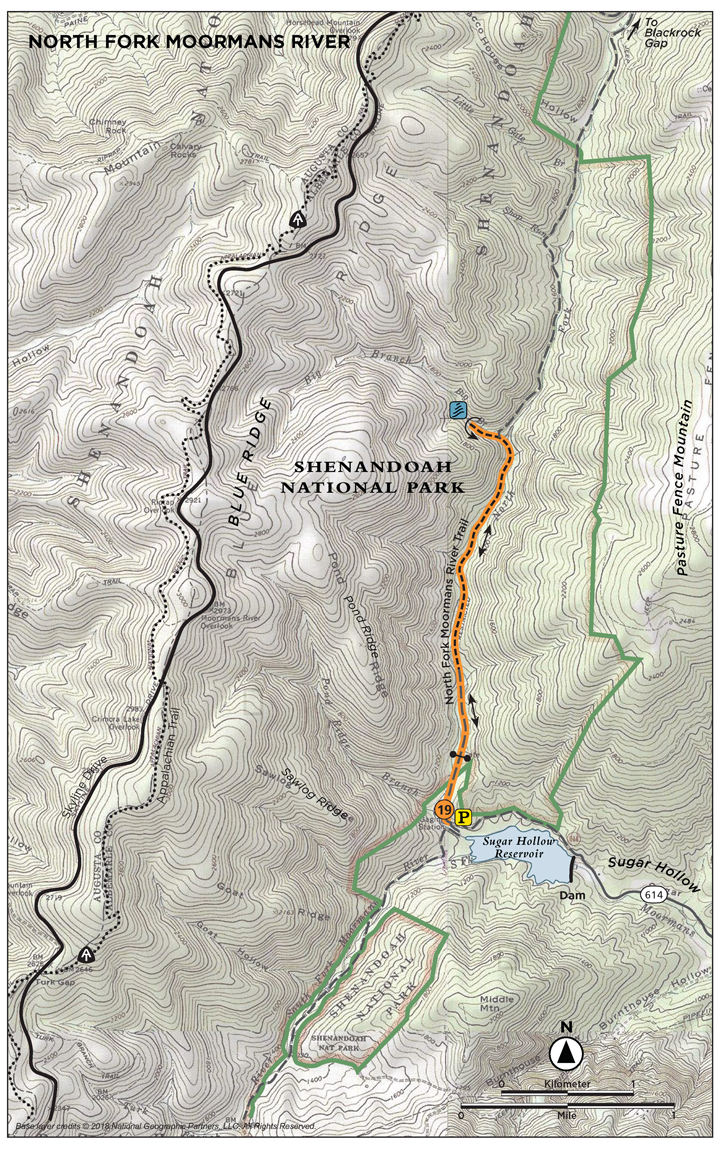

Start: National park boundary north of the Sugar Hollow Reservoir on VA 614 at the parking area for the North Fork Moormans River Trail

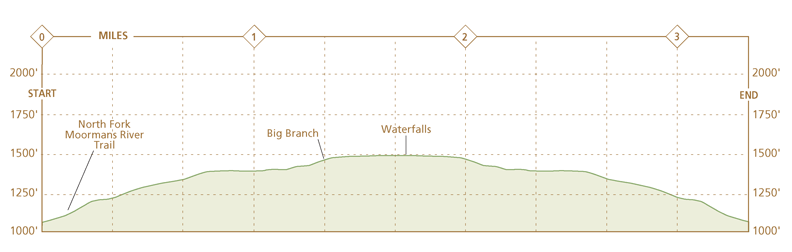

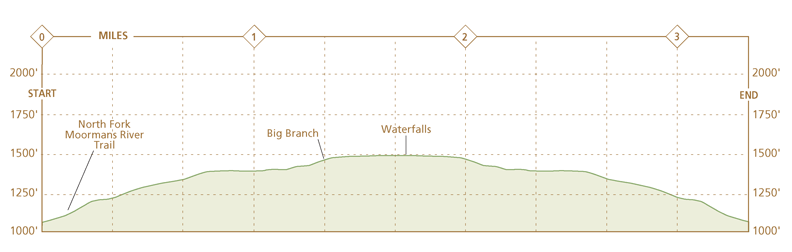

Distance: 3.4 miles out and back

Hiking time: About 3 hours

Difficulty: Easy due to short distance and level terrain. There are dangerous passages across rock slides and undercut stream banks, however.

Trail surface: Mostly dirt roads and occasional streambeds wind through an expansive stream valley hewn by floodwaters and fed by numerous small mountain streams. One tributary, Big Branch, drops 50 feet off barefaced rock into a deep pool.

Land status: National park

Nearest town: White Hall, VA

Other trail users: Mountain bikers, cross-country skiers, and anglers

Accessibility: The John Kostanecki Memorial Trail provides access to Moormans River for anglers with mobility impairments.

Canine compatibility: Leashed dogs permitted (leash no longer than 6 feet)

Trail contact: Shenandoah National Park, 3655 US 211 East, Luray; (540) 999-3500; www.nps.gov/shen

Schedule: Open year-round. The trail starts outside the park, so you do not need to use Skyline Drive, which may close due to inclement weather.

Fees/permits: Since you enter from outside the park, you do not need to pay the entrance fee. Free backcountry camping permits, available at ranger stations and visitor centers between sunrise and 1 hour before sunset, are required. Campfires prohibited except in established fireplaces at AT shelters. Before visiting, review backcountry regulations, which cover such issues as group size, where to camp, and waste disposal. Call (540) 999-3500 for regulations. To fish in Shenandoah National Park (SNP), Virginia residents age 16 or older must have a Virginia state fishing license.

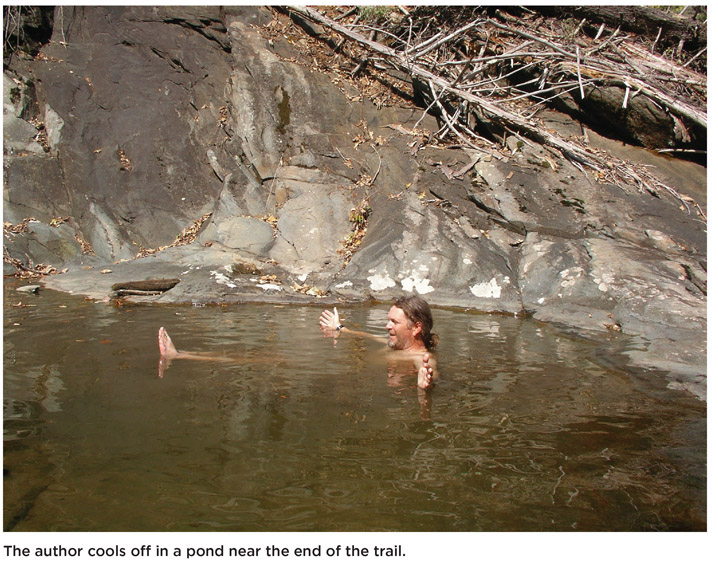

Facilities/features: No facilities. There are numerous swimming holes as you hike up the river bottom.

NatGeo TOPO! map: Browns Cove, Crimora

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Shenandoah National Park; Appalachian Trail, Calf Mountain to Raven Rock

Other maps: PATC #11: Shenandoah National Park South District

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From White Hall, drive 5.6 miles west on VA 614 to Sugar Hollow Reservoir Past the reservoir dam, the road turns to gravel. Follow it to a parking area that marks the end of vehicle access. This is land owned by the City of Charlottesville. There is no public vehicle access into Shenandoah National Park beyond this point. Do not block the gate in case it is needed for emergency access to the park. Parking spaces fill quickly on weekends. GPS: N38 08.641’ / W78 44.912’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 67, C6.

From White Hall, drive 5.6 miles west on VA 614 to Sugar Hollow Reservoir Past the reservoir dam, the road turns to gravel. Follow it to a parking area that marks the end of vehicle access. This is land owned by the City of Charlottesville. There is no public vehicle access into Shenandoah National Park beyond this point. Do not block the gate in case it is needed for emergency access to the park. Parking spaces fill quickly on weekends. GPS: N38 08.641’ / W78 44.912’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 67, C6.

THE HIKE

Geologists study materials that form the earth, and the elements that work on those materials, like wind, water, heat, and pressure. They work with history, but on a scale so much larger and longer than the human time frame, it’s often difficult to fathom.

Not all geologic activity is ancient history, however. On the North Fork Moormans River, it appears uncomfortably recent. Streams look like a rogue bulldozer blew out banks 20 feet high. Trees, their exposed roots bleached by sun, lay mixed in with piles of rock rubble. Vines drape over unstable stream banks underlain by a mud-clay-rock conglomerate. Loose boulders show a fresh, rough aspect, a marked difference from smooth, rounded shapes expected along streambeds. From uprooted logs to piles of boulders waist-high, all signs point to a great force that swept down the river valley.

The cataclysmic event that caused this began on June 22, 1995. Rain fell throughout Shenandoah National Park for 6 days. On June 27 an intense storm pocket formed over the North Fork. Nine hours of hard rain followed. In a 2-hour period, the dam manager at Sugar Hollow Reservoir, which is fed by the North Fork, recorded 11.5 inches of water. A USGS report by geologists Benjamin Morgan and Gerald F. Wieczorek offers a chilling account of how quickly water rose.

At 7 p.m., Virginia Power had received reports of power failure in Sugar Hollow from residents below the dam. At 9—9:30p.m., a lineman rearming a safety device on a pole near White Hall, Virginia, found that water had suddenly risen up to his knees within a few minutes. Rapidly rising water to chest level flooded his truck before he could drive to higher ground.

White Hall is 6 miles downstream from the reservoir. Above the lake, no one witnessed what occurred along the North Fork Moormans River. If they did, there is no saying they’d be alive to describe it.

Trouble started on the steep slopes rising out of the stream valley. In this area of Shenandoah National Park, a thick coating of saprolite overlays the Blue Ridge rock complex of billion-year-old granite, greenstone, and Chilhowee sandstone. Saprolite has a claylike consistency that, under proper conditions, can loosen and shift. When this happens, other surface elements—topsoil, block fields, and loose rocks—will join the flow and create a landslide. In June 1995, all elements coalesced in a single spot—the North Fork Moormans River. What followed is described as a once-a-millennium geologic event.

Geologists documented more than one hundred landslides in a 5-mile area upstream from Sugar Hollow Reservoir. Soil slips and debris flows turned hillsides into liquid, muddy concoctions that ripped trees from their roots and moved boulders by the ton. Transported downstream, this material pummeled stream banks. Evidence of its power is visible a mile and a half upstream from the reservoir, on the right bank, where water cut a stream bank 20 feet high.

Up on mountain slopes west of the river, small streams became channels 100 to 200 feet wide. Big Branch, a stream that discharges into the North Fork at a spectacular waterfall, experienced an estimated water flow rate of 6,200 cubic feet per second. Amazingly, this means flow down Big Branch equaled, for a time, the rate of water flowing over Great Falls on the Potomac River (when the Potomac’s water level is at the low level of 3.5 feet above median). The National Park Service calls any flow rate a “guess,” given that there are no gauges on the river. Even so, their rough estimates exceeded the 500-year magnitude flood estimate by 155 percent.

As far as recreation use of the North Fork goes, little has changed since the flood. The trail is an old fire road that follows a gently ascending route into the folds of the Blue Ridge. Streams drop off the hillsides, often in small waterfalls. Great slabs of rock attract sunbathers and shutterbugs to the picture-perfect pool at the base of Big Branch. Veteran fly fishers practice their timing upstream. Their protégés stand knee-high in the stream, entangled in yards of fishing line while brook and brown trout swim around them.

The flood did turn a hike that has been, for most people, a convenient excuse to skip class or work, into a showcase of geologic activity. Rock slides that crossed the trail display stones of banded gneiss with its alternating light and dark streaks. Near Big Branch, the old road narrows to a footpath and crosses rock and debris flows halted by logjams. The trail here makes a short climb, then drops back to water level. Farther up the hillside a discerning eye can make out signs of forest recovery that the past two decades have fostered, primarily young saplings typical of forest regeneration. In dry streambeds, small trees sprout up through stone rubble. Naturalists have spotted the rare wildflower white monkshood. The brook and brown trout, temporarily flushed from the basin by the flood, have returned. A fish survey 2 weeks before the storm counted thirteen different species in the stream, including thirty brook trout; a survey after the storm netted six fish—total.

HEADS UP

This area has been suffering from overuse and some misuse on weekends in good weather. Please respect the regulations, and if you are looking for a wilderness experience, try to go midweek in the high season.

Not all areas are so quick to recover. Before the flood, trees, ferns, and other riverside plants crowded the mouth of Big Branch. Now it is bare rock. Quieter geologic processes have begun. Over hundreds of years, soil and weathered rock will build up. Small plants first, then trees, will sink roots. Someday, the flood of 1995 will be ancient history—which makes this chance to see its bare effects today all the more special.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start from the parking area at the reservoir.

0.1Reach the park trailhead where a signboard has details and a map, along with rules and regulations. Walk straight (north) on the North Fork Trail. Yellow blazes are infrequent.

0.4Cross the North Fork Moormans River. All crossings are by fording, no bridges. Note: Upstream right, the river undercuts a rock face that offers a close-up view of the Catoctin formation, which underlies the east side of the stream. This geologic formation is made up of metabasalts, or ancient lava flows, that oozed from the earth and hardened.

0.5Cross the river again. Note: There is a nice swimming hole upstream from this crossing. Also, at low water, the streambed itself is hikeable by rock hopping for those seeking variety on this short hike.

1.1Cross the river again. As you hike upstream, scan the opposite bank for evidence of the 1995 flood, here illustrated by sheer banks up to 50 feet high that were carved by the debris flow that moved through this stream valley.

1.4Pass through an area of widespread destruction caused by the 1995 flood. Although now two decades later, there are still signs of landslides that moved the trees and rocks seen here, a force strong enough to snap tree trunks. On the left, uphill, a washout illustrates how wide an area these landslides affected.

1.5Descend to the river’s edge. Turn left and climb to the falls on Big Branch, a few yards uphill. Turn back and return to the parking area on the North Fork Trail. (Take time to explore Big Branch. Once a small stream, it has been forever altered by the storm. The lower falls, especially, show signs of being blown out by massive floods of water pouring off the slope.) Side trip: North Fork Trail continues past Big Branch to reach Blackrock Gap on Skyline Drive in 3.7 miles. A section of this route upstream leaves the national park for 1.2 miles, then reenters the park to climb steeply up a stream hollow to Skyline Drive, an alternative entry and parking

3.4Arrive back at the parking area.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Visit Charlottesville, (877) 386-1103, www.visitcharlottesville.org

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

Crozet Arts and Crafts Festival, May and Oct, Crozet, (434) 326-8284, www.crozetfestival.com

White Hall Vineyards, White Hall, (434) 823-8615, www.whitehallvineyards.com

Monticello, Charlottesville, (434) 984-9800, www.monticello.org. Thomas Jefferson’s home, featuring a restored orchard, vineyard, and gardens. Open every day except Christmas.

LODGING

Inn At Sugar Hollow Farm, Crozet, (434) 260-7234, www.sugarhollow.com. Pet-friendly. Located on VA 614 west of Charlottesville.

Park lodges at Skyland (Mile 41.7 and 42.5), Big Meadows (Mile 51.2), and cabins at Lewis Mountain (Mile 57.5) are seasonal. Call (877) 247-9261 or go to www.goshenandoah.com for reservations.

Campgrounds are located at Matthews Arm (Mile 22.2), Big Meadows (Mile 51), Lewis Mountain (Mile 57.2), and Loft Mountain (Mile 79.5). Some are first-come, first-served. For campground reservations, call (877) 444-6777 or visit www.recreation.gov.

Six backcountry cabins are operated by the PATC. For reservations, call (703) 2420693 or visit www.patc.net.

RESTAURANTS

Crozet Pizza, 5794 Three Notch’d Rd., Crozet, VA 22932; (434) 823-2132; www.crozetpizza.com. Famous for its hand-tossed pies.

Numerous restaurants in Charlottesville provide ample dining opportunities after a long hike.

Full-service restaurants are located at Big Meadows Lodge (Mile 51.2) and Skyland (Mile 41.7 and 42.5), and Wayside Food Stops at Elkwallow Wayside (Mile 24.1), Big Meadows Wayside (Mile 51.2), and Loft Mountain Wayside (Mile 79.5). All restaurants are seasonal. Visit www.goshenandoah.com for information.

HIKE TOURS

Ranger-guided programs are offered spring, summer, and fall.

For commercial tour operators that are permitted in the park, visit www.nps.gov/shen/planyourvisit/permitted-business-services.htm.

OTHER RESOURCES

Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), Vienna, (703) 242-0315, www.patc.net. Publishes maps and guides and sponsors hikes in the park.

Shenandoah National Park Association, Luray, (540) 999-3582, www.snpbooks.org. A nonprofit partner that sells guidebooks, maps, brochures, and CDs on the history, flora, and fauna of Shenandoah National Park, to benefit park activities.

From White Hall, drive 5.6 miles west on VA 614 to Sugar Hollow Reservoir Past the reservoir dam, the road turns to gravel. Follow it to a parking area that marks the end of vehicle access. This is land owned by the City of Charlottesville. There is no public vehicle access into Shenandoah National Park beyond this point. Do not block the gate in case it is needed for emergency access to the park. Parking spaces fill quickly on weekends. GPS: N38 08.641’ / W78 44.912’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 67, C6.

From White Hall, drive 5.6 miles west on VA 614 to Sugar Hollow Reservoir Past the reservoir dam, the road turns to gravel. Follow it to a parking area that marks the end of vehicle access. This is land owned by the City of Charlottesville. There is no public vehicle access into Shenandoah National Park beyond this point. Do not block the gate in case it is needed for emergency access to the park. Parking spaces fill quickly on weekends. GPS: N38 08.641’ / W78 44.912’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 67, C6.