23. STEPHENS TRAIL

WHY GO?

Camp Roosevelt opened in 1933 as America’s first Civilian Conservation Corps camp. Living in tents and earning $30 a week, unemployed men built the roads, campgrounds, picnic shelters, and fire towers we still use today. Their handiwork included a limestone block tower and shelter on Kennedy Peak. Its squat, low-rising design often surprises hikers expecting a tall lookout, but it’s still high enough to give commanding views off the 2,600-foot Kennedy Peak. Eastward lies Page Valley and to the west Shenandoah Valley, both outlined with patchwork farms, towns, and forests.

THE RUNDOWN

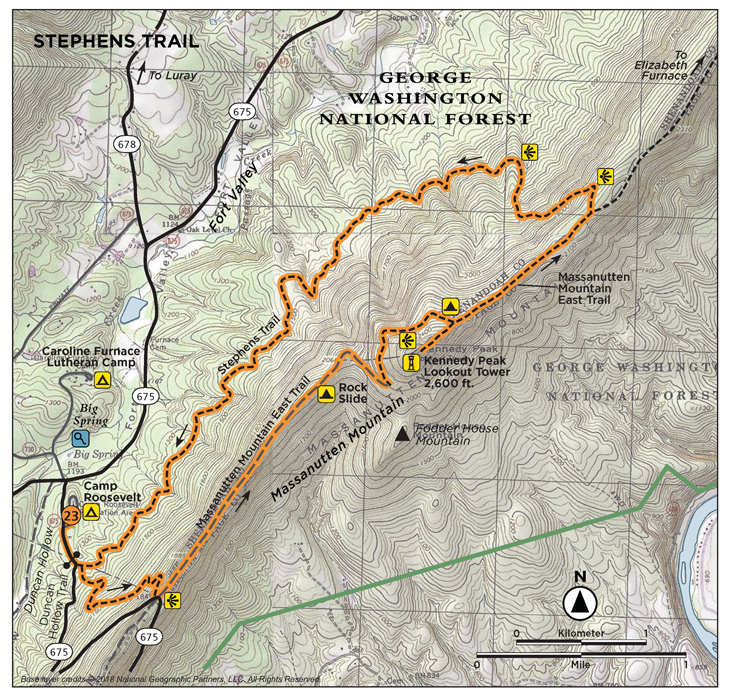

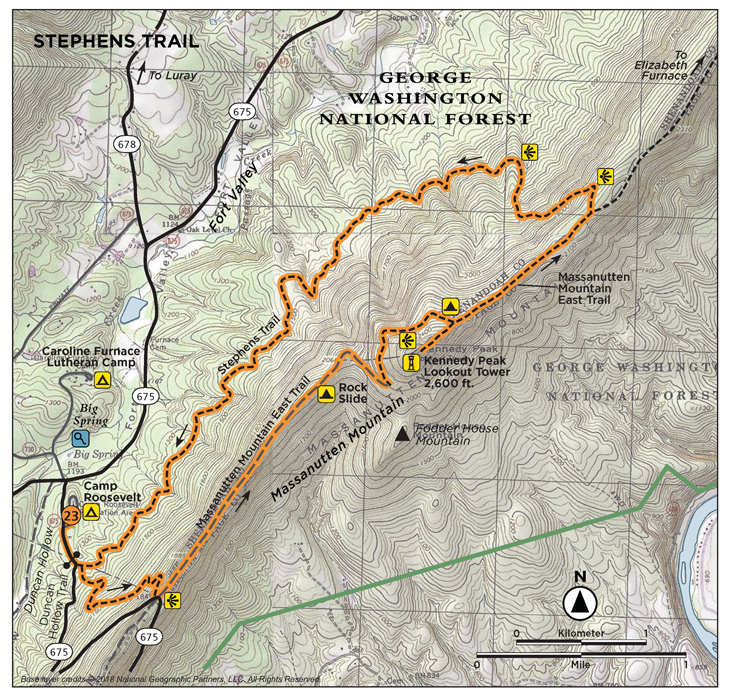

Start: Camp Roosevelt Recreation Area

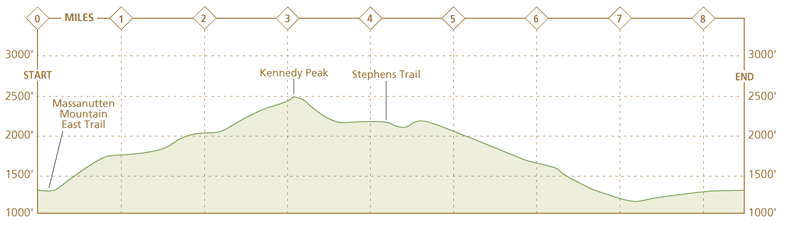

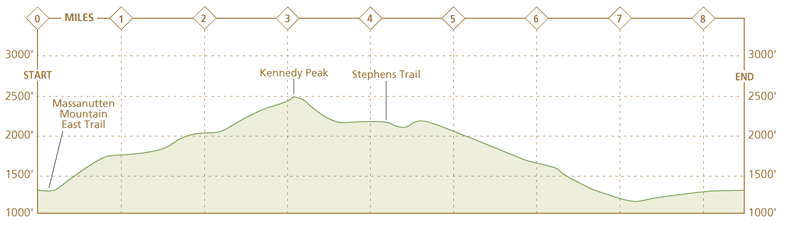

Distance: 8.5-mile loop

Hiking time: About 5 hours

Difficulty: Easy, with a few climbs and most of the trail following old logging roads

Trail surface: Dirt footpaths and dirt forest roads lead to ridgetops, forest coves, and the craggy Kennedy Peak, with views of the Blue Ridge and Allegheny Mountains.

Land status: National forest

Nearest town: Edinburg, VA

Other trail users: Mountain bikers, equestrians, cross-country skiers, and hunters (in season)

Accessibility: The 0.5-mile Lions Tale Accessible Trail is just a few miles south of Camp Roosevelt on FR 274 (Crisman Hollow Road).

Canine compatibility: Dogs permitted

Trail contact: Lee Ranger District, Edinburg; (540) 984-4101; www.fs.usda.gov/gwj

Schedule: Open year-round. Camp Roosevelt is open May through Oct. Hunting is permitted in national forests, with the busiest season Nov to early Jan.

Fees/permits: Camping fee

Facilities/features: Camp Roosevelt has flush toilets, drinking water, and campsites.

NatGeo TOPO! map: Hamburg, Luray, Rileyville, Edinburg

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Massanutten and Great North Mountains; Shenandoah National Park

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From I-81 in Edinburg: take exit 279. Turn east on VA 675. At the intersection of US 11 and VA 675 in the center of Edinburg, turn left onto US 11. Make another right to turn back onto VA 675 at the north end of Edinburg. Follow VA 675 for 5.9 miles over Massanutten Mountain to a stop sign at Kings Crossing. Turn right and continue on VA 675 for 3.4 miles to intersection of VA 675, FR 274, and VA 730. Turn left, still on VA 675. Camp entrance is 0.3 mile up, on the left side of the road. GPS: N38 43.883’ / W78 31.024’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 73, C7; Page 74, B1.

From I-81 in Edinburg: take exit 279. Turn east on VA 675. At the intersection of US 11 and VA 675 in the center of Edinburg, turn left onto US 11. Make another right to turn back onto VA 675 at the north end of Edinburg. Follow VA 675 for 5.9 miles over Massanutten Mountain to a stop sign at Kings Crossing. Turn right and continue on VA 675 for 3.4 miles to intersection of VA 675, FR 274, and VA 730. Turn left, still on VA 675. Camp entrance is 0.3 mile up, on the left side of the road. GPS: N38 43.883’ / W78 31.024’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 73, C7; Page 74, B1.

THE HIKE

Spotted wintergreen’s tolerance of poor soil makes this exotic-looking plant stand out amid the otherwise drab mountain slope leading to Kennedy Peak. From the flower’s telltale green-and-white leaves rises a single, top-heavy stem crowned by five white petals that arc backward. To see the green plug-like pistil and pale yellow stamens, gently lift the flower and peek beneath.

Dry forest conditions breed more than curious-looking wildflowers. They breed forest fires, the threat of which prompted Jack Stephens to walk from his home in Fort Valley to Kennedy Peak on a regular basis. Stephens’s route up Kennedy Peak varied little. From Fort Valley, he climbed on switchbacks to a small saddleback between what is now called Stephens Pass. Turning right, he walked atop the narrow Massanutten Ridge, then made his way up the steep, rocky hill to the fire tower.

Stephens’s route is now engraved into the slope of Massanutten Mountain by a generation of hikers and horseback riders. Blueberries and scrub oak crowd the forest understory, a monotone landscape highlighted in places by very colorful spotted wintergreen. Grouse and turkeys and deer inhabit this woodland, too. In the saddlebacks between small knobs, grass grows waist-high. Trees are spaced and signs of old orchards and stone walls are visible.

The advantages of a tower on Kennedy Peak are clear from the moment you ascend. Massanutten Mountain stretches 55 miles from Front Royal to Harrisonburg, and along its entire length there are few if any steep or dramatic interruptions. Kennedy Peak is the exception, sticking up 200 feet from the main trunk just before the ridge descends to a small gap. The knob, barren of trees, affords unblocked views in all directions. If you could peer back in time from here as well, you would witness a time when local wardens received $5 a year to monitor fire activity in a newly created national forest. The period was World War I, and two forest units existed in northern Virginia, the Massanutten and Potomac Districts. To build pride and win over suspicious locals, the forest supervisor fostered a rivalry between them. For 3 years—1913 to 1916—wardens from each side met for a tug-of-war at the Shenandoah County Fair. The winner took home bragging rights and a wooden Forest Service shield. The rivalry ended in 1917 when the two districts merged. (For the record, Massanutten District won the tug-of-war twice, Potomac once. Both regions fall within the present-day Lee Ranger District.)

Where Stephens Trail retraces the footsteps of one man, a different route to Kennedy Peak, on the Massanutten East Trail out of Camp Roosevelt, follows the steps of hundreds of men. The first Civilian Conservation Corps camp opened at Camp Roosevelt in 1933, and for nearly a decade following, unemployed men and World War I veterans spread across what was then Shenandoah National Forest (the name was later changed to George Washington National Forest to avoid confusion with Shenandoah National Park). Nicknamed Roosevelt’s Tree Army, these men planted trees to replace the acres clear-cut for charcoal and timber. To build the Kennedy Peak fire tower, they carried limestone blocks quarried from the mountains.

Limestone proved a valuable commodity for others, too: Early American blast furnaces required limestone to make pig iron. Along Stephens Trail, hikers can see clearly the red cake-like rocks, some the size of bricks, that iron ore producers craved. These stones are hematite-laden; the red color ensured prospectors that the rocks would produce good-quality iron. They were carted off to local blast furnaces, where molten pig iron flowed out of the bottom of the furnace into molds for pots and kettles and tools.

During the Civil War, blast furnaces shifted production. Out of mountain ironworks such as Elizabeth Furnace and Catherine Furnace came the bullets, cannons, and guns that supplied Confederate troops. General Stonewall Jackson stated, “If the Valley is lost, Virginia is lost,” and embarked on the Valley Campaign of 1862 to ensure that wouldn’t happen. Battles at Kernstown, McDowell, Cross Keys, and Front Royal kept the Valley in Confederate hands until 1864, when Northern general Philip Sheridan began sweeping through the Shenandoah Valley, burning homes, looting supplies, and slaughtering livestock.

The best view from Kennedy Peak lies west, across the northern Shenandoah Valley. This is the valley traveled by Quakers and Scots-Irish from Pennsylvania and Maryland in the early 1700s. With their arrival, two Virginias evolved. In coastal regions, a few wealthy landowners controlled land and an economy based on tobacco and slave labor. Mountain Virginia reflected the religious fervor of German and Scots-Irish immigrants. Wheat fared better here than tobacco, due in part to limestone-rich soil. Nicknames for these two Virginians developed: Easterners were Tuckahoes, a term derived from the arum root that grows around marshes; western Virginians were Cohees, slang derived from “Quothe he,” a reflection of the settlers’ strong religious backgrounds.

From the Cohees’ valley towns, Massanutten Mountain appears as a single, continuous ridge. At its northern reach, the bedrock divides into two ridges separated by a bowl-like depression called Fort Valley. In the 1700s, English colonists built a fort here for trading and protection against the French and Native Americans. The boast “Washington Slept Here” rings true in Fort Valley and neighboring towns such as Winchester and Front Royal. These mountains and valley were a proving ground for the young George Washington, who first visited as a surveyor for Lord Fairfax, and then as an officer in the Virginia militia.

The views off Kennedy Peak show that a century of human progress has erased physical signs of the destruction of the past. The whole of Massanutten Mountain appears separate from the valley that unfolds at its feet. In reality, it is just the opposite. You cannot remove the mountain from the valley. Nor would it seem right to do so.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start at the entrance of Camp Roosevelt. Turn left and walk up VA 675 to a white forest gate on the left in 0.1 mile. Note: On the right side of the road is a trailhead for Duncan Hollow Trail. It leads south to New Market Gap.

0.1Turn left onto the orange-blazed Massanutten East Trail. It climbs uphill past the white forest gate.

0.2Enter a clearing, turn right, and climb on the Massanutten East Trail. The trail passes under a set of power lines several times and narrows from a dirt road into a footpath. Note: There is an equipment shed in the clearing. Note: The trail that leads straight past the shed is Stephens Trail, the return leg of this loop.

0.8The trail reaches VA 675. Turn left and walk 50 yards up the left side of the road, reentering the woods on a forest road. There is an impressive view over Fort Valley on the side of VA 675.

1.9Massanutten East Trail branches right from the dirt road to circumvent a knob. In 0.2 mile, the trail repeats this pattern. There are nice views here, across Fort Valley to Massanutten Mountain’s west ridge.

2.2Pass a campsite on the right side of the trail. Kennedy Peak is visible at this point.

2.4The trail switchbacks northwest amid a rock slide.

2.6Where the trail bends right around the side of Kennedy Peak, there are good views west over Fort Valley. At shoulder height on your right side, thick slabs of sedimentized rock stick out of the hillside at a 45-degree angle.

3.2Reach the spur trail to Kennedy Peak. Turn right and make the short, 0.2- mile uphill trek to a stone shelter/lookout tower constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps stationed at Camp Roosevelt in the 1930s. Return to the Massanutten East Trail and hike north atop the ridge.

4.0Where the trail drops briefly off the right side of a knob, look for exposed sections of rock that show the layered sandstone rock formations. This is Massanutten sandstone, light gray and highly resistant rock.

4.2Stephens Trail branches left while Massanutten East Trail continues a northward route to Elizabeth Furnace. Turn left onto Stephens Trail and make a beeline through open hardwood forest. Where the downslope pitch steepens, the trail switches back to descend along the northwest flank of Massanutten Mountain. Watch for red flinty rocks underfoot, indicative of the iron ore deposits found in the mountain bedrock.

5.3As you wrap around a shoulder ridge and begin a lateral descent on the wavy course of Stephens Trail, there are good views over Fort Valley west. For 2 miles, the trail will alternate between moist coves and exposed hillsides as it crosses the many unnamed tributaries of Passage Creek, which flows through Fort Valley, a basin formed by the east and west ridges of Massanutten Mountain.

8.3Enter a clearing and hike straight past a junction with the Massanutten East Trail. The equipment shed is on your right.

8.4Reach VA 675. Turn right and walk downhill to Camp Roosevelt.

8.5Arrive back at Camp Roosevelt.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Shenandoah Valley Travel Association, New Market, (877) VISIT-SV, www.visitshenandoah.org

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

Edinburg Ole’ Time Festival, held in Sept, (540) 984-7272, http://edinburgoletimefestival.org

Luray Caverns, Luray, (540) 743-6551, www.luraycaverns.com. One of several commercial caves in the Shenandoah Valley. Guided tours available.

LODGING

Camp Roosevelt has fee camping near the trailhead, open late May through Oct, operated by the Lee Ranger District of the National Forest. Flush toilets and water, no hookups. (540) 984-4104.

The Widow Kips, Mount Jackson, (540) 477-2400, www.widowkips.com. Pets welcome in their guest cottages.

RESTAURANTS

The Spring House Tavern, Woodstock, (540) 459-4755, www.springhousetavern.net. Casual eatery with great food.

ORGANIZATIONS

Potomac Appalachian Trail Club (PATC), Vienna, (703) 242-0315, www.patc.net

Civilian Conservation Corps Legacy, www.ccclegacy.org

From I-81 in Edinburg: take exit 279. Turn east on VA 675. At the intersection of US 11 and VA 675 in the center of Edinburg, turn left onto US 11. Make another right to turn back onto VA 675 at the north end of Edinburg. Follow VA 675 for 5.9 miles over Massanutten Mountain to a stop sign at Kings Crossing. Turn right and continue on VA 675 for 3.4 miles to intersection of VA 675, FR 274, and VA 730. Turn left, still on VA 675. Camp entrance is 0.3 mile up, on the left side of the road. GPS: N38 43.883’ / W78 31.024’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 73, C7; Page 74, B1.

From I-81 in Edinburg: take exit 279. Turn east on VA 675. At the intersection of US 11 and VA 675 in the center of Edinburg, turn left onto US 11. Make another right to turn back onto VA 675 at the north end of Edinburg. Follow VA 675 for 5.9 miles over Massanutten Mountain to a stop sign at Kings Crossing. Turn right and continue on VA 675 for 3.4 miles to intersection of VA 675, FR 274, and VA 730. Turn left, still on VA 675. Camp entrance is 0.3 mile up, on the left side of the road. GPS: N38 43.883’ / W78 31.024’. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 73, C7; Page 74, B1.