25. LAUREL FORK AREA

WHY GO?

Laurel Fork once ranked as a top site in Virginia for wilderness protection, but strong opposition from inholders—families who own private property inside national forest boundaries—beat this proposal back. The desire to keep this place forever wild is understandable. There’s a whiff of spruce in the air. Songbirds trill and peep in the bushes. Pine needles pile thick on the forest floor. Streams wriggle around and over the deadfall and boulders strewn in their path by storms and hurricanes. Native trout swim the Laurel Fork. It has been a long 70 years since loggers cleared the red spruce and fir trees. Nature has reclaimed Laurel Fork fully, and for this, we’re all better off.

THE RUNDOWN

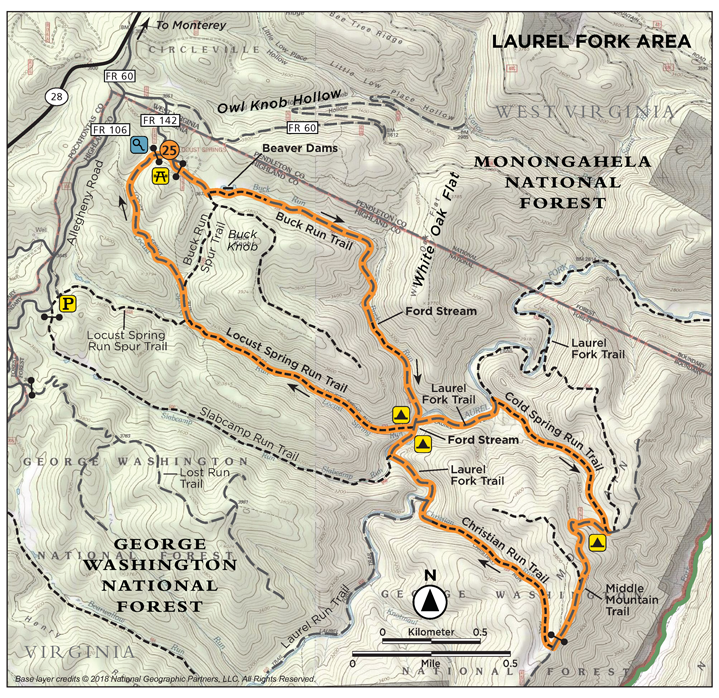

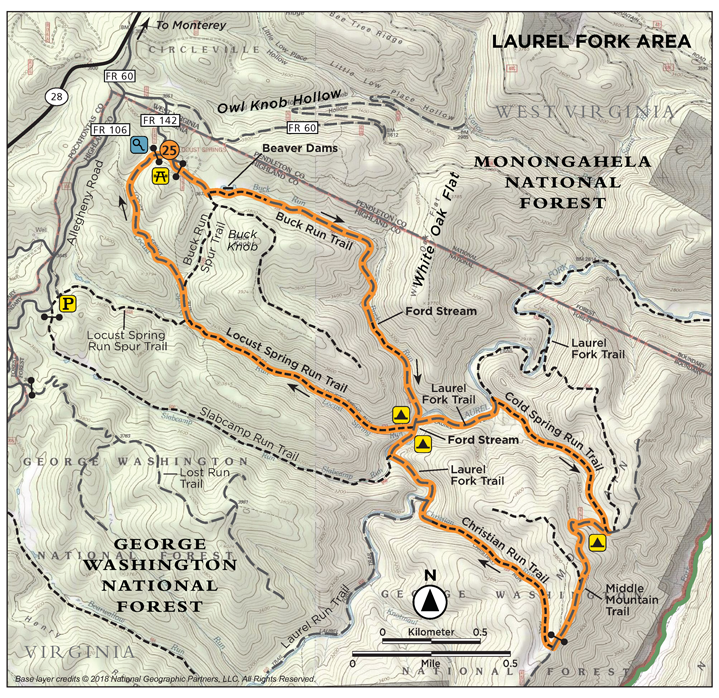

Start: Locust Springs Picnic Area

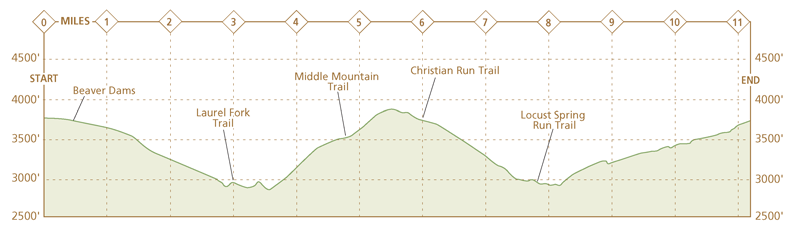

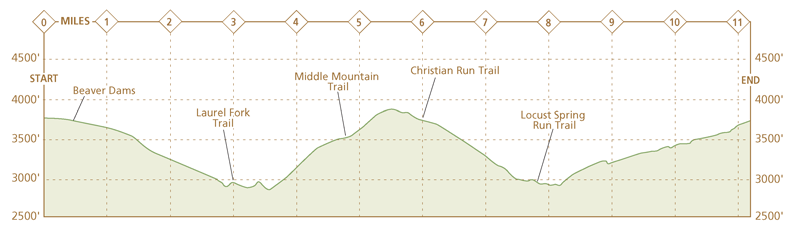

Distance: 11.2-mile double loop

Hiking time: About 6 hours

Difficulty: Moderate due to numerous stream crossings and steep trails up Middle Mountain that merge with streambeds. Because of its elevation, Laurel Fork receives heavy snowfall in winter.

Trail surface: Dirt footpaths and old forest roads wind through highaltitude red spruce forests and stream coves.

Land status: National forest

Nearest town: Monterey, VA

Other trail users: Mountain bikers, equestrians, and hunters (in season)

Accessibility: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs permitted

Trail contact: Warm Springs Ranger District, Hot Springs; (540) 839-2521; www.fs.usda.gov/gwj

Schedule: Open year-round. Hunting is permitted in national forests, with deer season running from Nov through early Jan.

Fees/permits: None.

Facilities/features: The Locust Springs Day Use Area has a vault toilet, but no drinking water.

NatGeo TOPO! map: Thornwood, Snowy Mountain

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Staunton, Shenandoah Mountain

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From Monterey, drive west on US 250. In 22 miles, turn right onto WV 28 and drive north for 6.7 miles. Turn right onto FR 60/FR 106, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. In 0.3 mile, bear left onto FR 60. At a second intersection in 0.3 mile, bear right and uphill, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. The picnic area is on the right on FR 142 in 0.4 mile. GPS: N38 35.129′ / W79 38.527′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 64 (inset), A1.

From Monterey, drive west on US 250. In 22 miles, turn right onto WV 28 and drive north for 6.7 miles. Turn right onto FR 60/FR 106, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. In 0.3 mile, bear left onto FR 60. At a second intersection in 0.3 mile, bear right and uphill, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. The picnic area is on the right on FR 142 in 0.4 mile. GPS: N38 35.129′ / W79 38.527′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 64 (inset), A1.

THE HIKE

Laurel Fork is a classic mountain stream, appreciation of which requires little effort. A big boulder helps. Sit on the rock and stare. In early morning hours a haze wraps around overhanging branches. Spray tossed up by the water sparkles. And just like that, an entire day watching birds flit from branch to branch seems a reasonable proposition.

It would, however, preclude exploration of the 10,000 acres in Laurel Fork Special Management Area. The steep west slope of Middle Mountain beckons. Up Christian Run or Cold Spring Run, the narrow footpaths are overrun with rhododendron. Trails and creeks intermingle without regard. The moss is spongy. There’s a dank smell of moist, decomposing leaves. When the trails widen, the earth buckles and ripples where railroad ties were once embedded. Laurel Fork was privately owned until 1922. Railroads chugged up and down the mountain slopes carrying workers in and logs out. Today’s trail network follows these grades, and rusted cast-iron remains of old railroad engine parts lie near the junction of Bearwallow Trail and Laurel Fork Trail.

Loggers were after the red spruce that gives Laurel Fork a unique aura. Much of it went to pulp mills. The highest-quality boards, craftsmen used in musical instruments; they preferred spruce to other woods because of its consistent growth patterns. Consider that a felled tree exhibits growth rings of varying size. Thick rings indicate the salad years, when sunlight and water were plentiful. Narrow rings reflect leaner times. Spruce somehow avoids these highs and lows; its growth rings are almost always the same size and compact, two qualities favorable for musical instruments. (Another interesting aside: The older the instrument, the better it sounds—but that’s only if it’s played, not left under glass to age. Wood becomes elastic with vibration, so an old wood instrument can sound as poor as one made of “green” wood if left untouched.)

For a hiker whose exposure to needle-leaf trees extends from jack pine to hemlock, a spruce forest can seem like an altered state. Technically, Laurel Fork is an “Appalachian extension of a northern boreal forest.” Nontechnically speaking, it’s cold, snows like crazy in winter, and harbors animals normally found farther north. If you’re lucky, a snowshoe hare might hop across the trail. The distribution map for this animal shows a shaded area over all of Canada and parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and New York. The map also shows fingerlike extensions reaching down the chain of Appalachian Mountains as far south as the Great Smoky Mountains in Tennessee. This sums up nicely the whole boreal forest effect. Glaciers never reached as far south as Virginia (as indicated by the dearth of natural lakes). But even if the ice never made it, the northern species of trees and animals suited for that environment did.

Buck Run Trail is a good introduction to the habitat. From Locust Springs Picnic Area the trail leads first past beaver dams. In the backwaters of all the major drainages— Buck Run, Slabcamp Run, and Bearwallow Run—you’ll find sizable beaver populations. Their handiwork is not confined to dams. Springtime finds logs felled across trails; the gnawed pointed trunk gives away the culprit. The shallow ponds created by the dams are thick with salamanders and frogs and the shrill of spring peepers.

One of the trees you’ll see along with the red spruce is the Fraser fir. In 1784 the tree’s namesake, John Fraser, a Scotsman, sailed into Charleston hoping to follow in the footsteps of his contemporaries, William Bartram and Andre Michaux, botanists who made names for themselves studying the flora and fauna of the Southern Appalachians. Fraser was an amateur, primarily concerned with making a fortune (why he chose botany as a career is a mystery). He roamed the Southern Appalachians collecting specimens for the highest bidder. His short list at times included the king of England, Catherine the Great of Russia, and her successor, Czar Paul. For a brief period, Fraser and Michaux traveled together, but their competing interest (Michaux was sending samples to Louis XVI of France) soon caused them to part company. Michaux let Fraser travel ahead, and, as a result, Fraser had the good fortune of being the first to discover the tree that now bears his name.

Nature is an exact science, down to the arrangement of needles on a red spruce branch. Clusters of needles minimize heat loss and keep the tree branch warm through the winter. The interlocking branches weave a canopy that blocks out sun and lends everything below a gloomy aspect. Thick piles of fallen needles mat the forest floor. Moist green sphagnum moss covers roots and rocks. Besides moss, little else grows under a mature spruce-fir forest canopy. It’s a vicious little circle, whereby needles and moss give the soil a high acid content, and the acid soil in turn slows decomposition. The moss, especially, thrives by coating dead logs and whatever else will host it.

The red spruce that dominate in Laurel Fork are well suited for life here. The soil is thin, a product of years of logging and erosion. The tree spreads wide, shallow roots into this soil. Porcupines like to nibble on the sweet bark of these trees, while red squirrels seem adept at extracting seeds from cones. Berry shrubs sprout and survive to feed a host of birds and small rodents through the lean winter months. Bearberry and prickly gooseberry mingle with the more readily identified high- and low-bush blueberries.

When West Virginia seceded from Virginia after the outbreak of the Civil War, it took with it some of the roughest natural terrain on the East Coast. Virginia’s valleys and ridges seem downright pastoral when compared to the jumble of peaks, cliffs, and ridges that form the Allegheny Mountains in West Virginia. Virginia can at least take some comfort in having kept this corner of Highland County and the Laurel Fork watershed.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start at the Locust Springs Picnic Area. Walk up a dirt road at the east end of the picnic area. Almost immediately, look for a gated forest road on the right, marked with blue blazes and a hiker sign. This is the Buck Run trailhead. Turn right, pass by the gate, and follow the road.

0.4Turn left off the grass road. Pass through a stand of red spruce. The ground is flat and the trail is now a dirt singletrack. There are several beaver dams in this area. Note: Buck Run Spur Trail is straight ahead on the grass road.

1.3The trail descends off the side of Buck Knob and switchbacks five times as it drops to Buck Run.

1.6Cross Buck Run and walk downstream following the left bank. In 0.1 mile, recross Buck Run to the right stream bank. Note: From now until the junction with Laurel Fork Trail, note how the slopes on either stream bank host starkly different plants: The left slope is covered with rhododendron, while the right supports more hardwoods, and sparse at that. Many exposed rock formations on this leg make it a geologist’s delight, amateur or otherwise.

3.0Buck Run Trail ends at a junction with the Laurel Fork Trail. Turn left onto Laurel Fork Trail and cross the stream. After crossing, turn left and hike downstream. (In the river floodplain, yellow sundrops may be in bloom. Pink lady slippers and the white bell-shaped flowers of Solomon’s seal grow near the edge of the forest. Red elderberry displays its fruit in August.) Note: From the end of Buck Run Trail, Laurel Fork Trail also leads straight upstream and intersects Locust Springs Run Trail, Slabcamp Run Trail, and Christian Run Trail.

3.7Turn right and ascend on the blue-blazed Cold Spring Run Trail. The trail joins the stream for a short stretch, then widens to show signs of an old railroad bed.

4.7The ground levels on both sides of the trail as it enters a grassy meadow. Note: The fields on Meadow Mountain were cleared for grazing when the mountain was privately owned. Today, The Stamp, an inholding farther south on the mountain, remains the last piece of private property in the special management area.

4.9Turn right onto Middle Mountain Trail, following blue blazes.

6.0Pass a hunters’ camp on the left, by a Forest Service gate. A large field opens up on your left. Turn right and walk through a meadow. Blue arrows on trees on the right fringe of the field will guide you to where the Christian Run Trail enters the woods.

6.7The trail narrows and runs close to Christian Run. It crosses three times.

7.0Christian Run Trail junctions with Laurel Fork Trail. Turn right and walk along the right stream bank.

7.4Where Slabcamp Run Trail branches left and crosses Laurel Run, continue straight on Laurel Fork Trail. There are several good campsites on this stretch of trail, including one, just prior to crossing Laurel Fork, that overlooks a swimming hole.

7.6Cross Laurel Fork and hike along the left stream bank.

7.8Turn left onto Locust Spring Run Trail. The next 1.5 miles brings numerous stream crossings. In places, the stream and trail merge for some messy hiking.

9.9Bear right and away from a left-branching trail, which is Locust Spring Run Spur Trail. It leads to FR 106.

11.2Hike ends at the Locust Spring Picnic Area.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Highland County Visitor Center, 61 Highland Center Dr., Monterey; (540) 468-2551; www.highlandcounty.org

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

The Highland Maple Festival, held in Mar, Monterey, (540) 468-2550, www.highlandcounty.org/events/maple-festival. Celebrates the opening of the trees with a festival and camp tours.

LODGING

Highland Inn, (540) 468-2143, www.highland-inn.com. Monterey’s historic hotel right on Main Street.

RESTAURANTS

Highs Restaurant, Main Street, Monterey, (540) 468-1700. Serves breakfast, lunch, and dinner 7 days a week.

From Monterey, drive west on US 250. In 22 miles, turn right onto WV 28 and drive north for 6.7 miles. Turn right onto FR 60/FR 106, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. In 0.3 mile, bear left onto FR 60. At a second intersection in 0.3 mile, bear right and uphill, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. The picnic area is on the right on FR 142 in 0.4 mile. GPS: N38 35.129′ / W79 38.527′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 64 (inset), A1.

From Monterey, drive west on US 250. In 22 miles, turn right onto WV 28 and drive north for 6.7 miles. Turn right onto FR 60/FR 106, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. In 0.3 mile, bear left onto FR 60. At a second intersection in 0.3 mile, bear right and uphill, following signs for Locust Springs Picnic Area. The picnic area is on the right on FR 142 in 0.4 mile. GPS: N38 35.129′ / W79 38.527′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 64 (inset), A1.