26. ROARING RUN/HOOP HOLE

WHY GO?

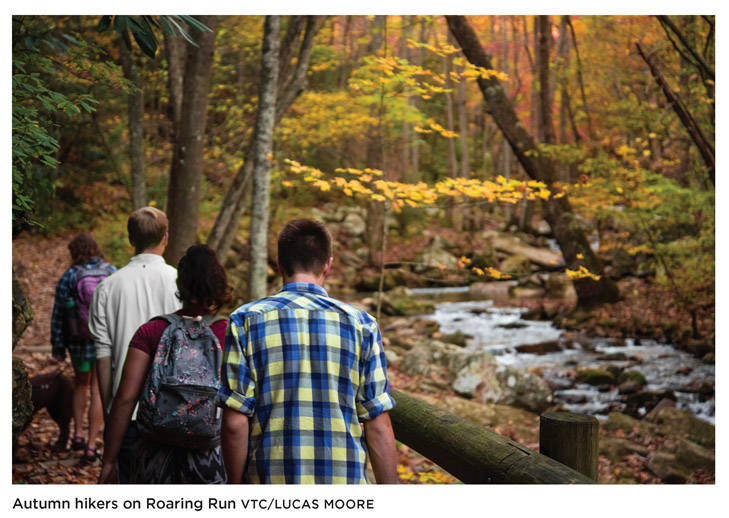

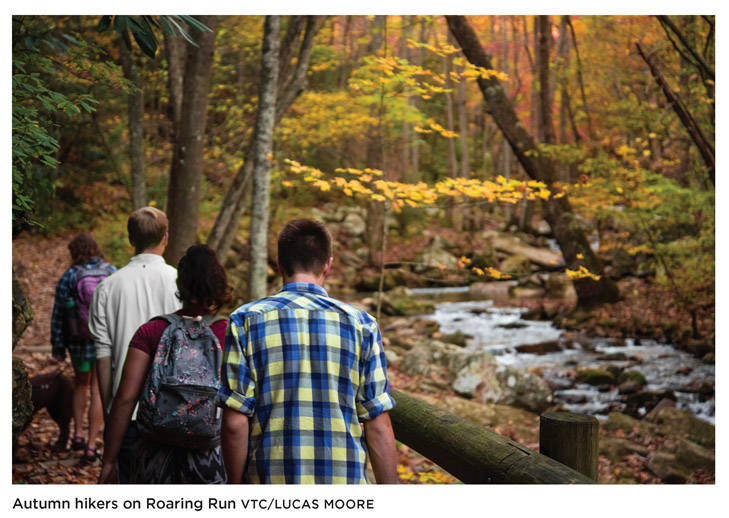

In an inconspicuous corner of Botetourt County, seven peaks converge to form a backcountry nook where bears just may outnumber human visitors. The region’s namesake, Roaring Run, pulses through a break in Rich Patch Mountain with force enough to have powered a blast iron furnace for half a century. Ruins of that furnace mark the beginning of a loop hike that takes you along the high, dry top of Pine Mountain, then down to headwaters of three small streams. Between ridgetop and riverbed spreads a forest that is as secluded as it is satisfying. For an easy, family-friendly hike, the 1.5-mile Roaring Run Falls Trail is easy and well-marked.

THE RUNDOWN

Start: Trail board next to the restrooms at Roaring Run Furnace National Recreation Area

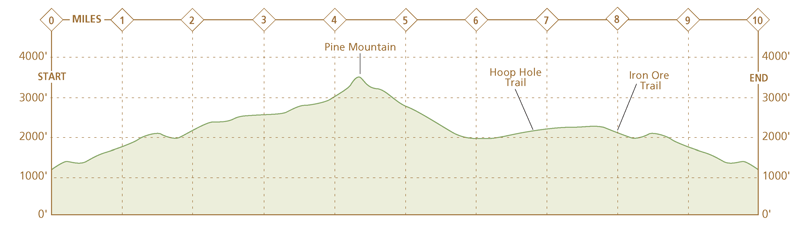

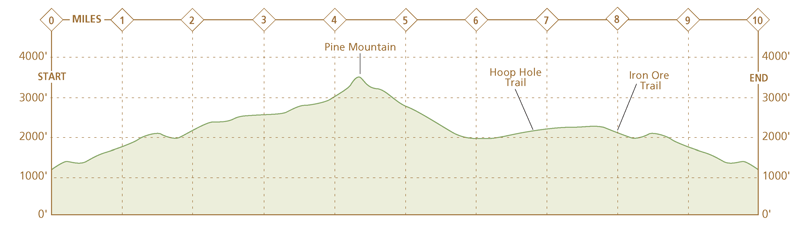

Distance: 10.0-mile lollipop

Hiking time: About 5 hours

Difficulty: Moderate due to long climbs and length. The bushwhack up Pine Mountain requires skills in across-country hiking, including the ability to use a compass.

Trail surface: Dirt footpaths and old dirt roads lead along dry ridges, through extended fields of heath, boulder fields, and stream headwaters.

Land status: National forest

Nearest town: Clifton Forge, VA

Other trail users: Hikers only

Accessibility: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs permitted

Trail contact: Eastern Divide Ranger District, Blacksburg; (540) 552-4641; www.fs.usda.gov/gwj

Schedule: Open year-round

Fees/permits: None

Facilities/features: Vault toilets and stream-side picnic sites

NatGeo TOPO! map: Strom

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Covington, Alleghany Highlands

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From Clifton Forge, drive west on I-64 to the Low Moor exit. Drive south on VA 696 and, in 0.1 mile, turn left onto VA 616. Drive 5.7 miles, then turn left onto VA 621 at Rich Patch Union Church. In 3.3 miles, turn right into the Roaring Run National Recreation Area. GPS: N37 42.400′ / W79 53.594′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 52, C3.

From Clifton Forge, drive west on I-64 to the Low Moor exit. Drive south on VA 696 and, in 0.1 mile, turn left onto VA 616. Drive 5.7 miles, then turn left onto VA 621 at Rich Patch Union Church. In 3.3 miles, turn right into the Roaring Run National Recreation Area. GPS: N37 42.400′ / W79 53.594′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 52, C3.

THE HIKE

In 1804 William Clark, a man whose name would become synonymous with exploration, left the small town of Fincastle in Botetourt County, Virginia, for the unknown of the American frontier. He and friend Meriwether Lewis would lead the Corps of Discovery through the void of middle America to the Pacific Ocean, and back. Three years later, Clark returned to Fincastle a national hero. He settled and married the daughter of wealthy landowner George Hancock. Clark’s journals from the Corps of Discovery expedition were stored and edited in Fincastle, in Hancock’s home. In 1810 President Thomas Jefferson appointed him governor of the Missouri Territory, thus ending his Virginia residency. Clark departed for St. Louis and left behind a legend proudly guarded by Fincastlians, who are known to claim their town as the real point-of-embarkation for the Lewis and Clark expedition.

Fincastle, a town of roughly 300 souls, is as fitting a beginning for Clark’s journey as any spot. For a brief period before the Revolutionary War, this town sat on the edge of the great unknown. The boundaries of Botetourt County, of which Fincastle was the county seat, stretched as far as the Mississippi and contained parts of seven present-day states. Standing atop Pine Mountain on a clear fall or winter day, you get a small sense of that vast landholding, where views stretch into West Virginia and the imagination, if prodded, farther. And as is the case for all good explorations, getting to this secluded vista on Pine Mountain is as much a reason for going as the payoff.

The journey begins at Roaring Run Furnace, a national recreation area south of Clifton Forge in Botetourt County. The Iron Ore Trail climbs from the ruins of a blast furnace on old dirt roads and abandoned railroad grades. In a saddle between Shoemaker Knob and Iron Ore Knob, the trail turns and skirts the slope of Pine Mountain as a footpath. If a hiker sticks to the blazed trails, the route eventually leads to a forested saddle of the Pine Mountain ridge. But there’s an alternate route up Pine Mountain, a short, steep path—more a detour than a true bushwhack. Look for this route as you climb Hoop Hole Trail, less than 0.5 mile uphill from the T intersection with Iron Ore Trail. In a world of well-blazed, clearly defined paths, this side trail is a gift. Marked by infrequent plastic squares the size of a quarter, following it still requires hunt-and-peck skills. These are times a hiker falls back on basic skills: orientating, identifying telltale plants, determining whether they are typical of a certain elevation or slope, and wondering who, or more precisely what, has walked here before you. (Lewis and Clark would be so proud.)

The last question is answered atop Pine Mountain. Amid the outcrops of sandstone, logs show signs of being clawed and shredded by black bears looking for larva and insects. By-products of their munching, scat piles, lay in clumps here and there. With a range up to 15 miles, a number of bears have made the Pine Mountain/Rich Patch Mountain slopes home turf.

From Pine Mountain’s first knob, a sight line carries southwest along the 3,000-foot-high ridge to a point where Pine Mountain buttresses against Rich Patch Mountain. Patches of stunted vegetation grow in thin shale soil on the upper slopes of the ridge. Berry bushes thrive here, where the larger, moisture-loving witch hazel will not. Wild grasses propagate in gaps of forest created by fire. Among the berry bushes, poverty oat grass grows in gray-green mats. Another grass, yellow sedge, is found on more gently graded slopes. Both grasses are present in early stages of forest recovery and may be indicators of a recent fire. The shoots need only a thin soil cover and seem adaptable to the acidic, nutrient-deficient soil typical of dry, fire-ravaged areas.

So thick is the undergrowth at points, Hoop Hole Trail can become difficult to follow. At these times, it pays to watch for the red stone flakes that litter the trail; this color indicates the mineral hematite. Hematite is a principal iron ore mineral and its presence, embedded in sandstone deposits formed 400 million years ago, helped catapult this region into a leading producer of iron ore during the second half of the 19th century.

Roaring Run Furnace, where this described loop begins, operated as a blast furnace for only 30 years. That’s a short time in a region famous for iron production. The furnace’s obscurity may explain, in a backhanded way, how it survived intact through the years. During the Civil War, Tredegar Iron Works leased Roaring Run as an insurance policy against losing its larger furnaces located in the Great Valley. Union forces eventually destroyed three of Tredegar’s mines in an effort to disrupt the Confederate’s supply of bullets, cannons, and gun parts. Tredegar, especially, held significance. From its Virginia furnaces, it produced the cannons at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, site of the first battle between North and South. And even Grace Furnace, an iron ore furnace 5 miles west of Roaring Run, fell to Union forces. It all points to a conclusion that Roaring Run survived because it wasn’t producing iron ore. Tredegar’s records show it blasted the furnace once, in 1865, just before the war ended. This inactivity made it an impractical target for Union forces.

Evidence of mining activity around Roaring Run Furnace is visible in the large depressions cut from the mountainside. In other spots, talus (rock piles) lay beneath gouged out chunks of hillside. For some unknown reason, the minerals around Roaring Run were never exploited to the extent they were elsewhere in Virginia. By 1870, Virginia iron furnaces were switching to a more efficient, coke-based fuel source. Charcoal-burning furnaces such as Roaring Run faded into obscurity. Given that a furnace consumed on average 750 bushels of charcoal in a single day—the equivalent of an acre of woodland—the furnace’s inactivity once again held an unintended benefit. This time, it saved a beautiful corner of the forest from mining and logging—a benefit hikers can certainly appreciate.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start from a trail board next to the restrooms at Roaring Run Furnace. Follow the wide, orange-blazed Iron Ore Trail under table mountain pines.

0.2At a fork in the trail, bear left and climb on the Iron Ore Trail. Soon, the falls on Roaring Run are audible downhill on the right.

0.4Pass under power lines.

0.7At a T junction, turn left and follow the orange-blazed Iron Ore Trail, which is still a dirt road. Note: Avoid the road that leads straight from this intersection. It is marked with yellow blazes.

0.8Pass a road that splits right and uphill away from Iron Ore Trail. In another 20 yards, Iron Ore Trail forks right onto a narrow trail leading uphill; bear right at this fork and follow the Iron Ore Trail uphill. It breaks from the woods to pass under power lines, then reenters the woods.

1.0Switchback up the northeast slope of Iron Ore Mountain. Iron Ore Trail climbs steadily to a gap between Iron Ore (2,117 feet) and Shoemaker Knob (2,429 feet). Iron Ore Trail is wide and well graded in sections where it follows old roads or railroad that date from a time in the 19th century when the blast furnace at Roaring Run was in operation.

1.7At a double blaze, turn left and cross the dry creek bed of Deisher Branch.

2.0Pass a campsite nicely situated in a large, flat clearing on the left side of Iron Ore Trail.

2.3At a T intersection, turn right onto the yellow-blazed Hoop Hole Trail. Note: A left onto Hoop Hole leads along the lower elevations of Pine Mountain. It is the return leg of this loop hike.

2.5Turn right on an overgrown path that leads sharply uphill. The route is marked with plastic yellow diamonds, about the size of a quarter, nailed into trees. Be alert: The trail is overgrown and hard to follow. Markers are small and infrequent. This route is a steep, 0.3-mile ascent of Pine Mountain’s first knob (2,789 feet). In fall and winter, this peak provides the best views off the mountain into West Virginia. Option: The climb up Pine Mountain’s first knob, while blazed, is difficult. A hiker can avoid it by continuing straight on the Hoop Hole Trail. A half-mile from this junction, Hoop Hole Trail enters a clearing in a saddle between Pine Mountain’s first and second knob. In this clearing, the route from Pine Mountain’s first knob rejoins Hoop Hole Trail.

2.8At the top of Pine Mountain’s first knob, turn left onto an overgrown trail marked with faint yellow paint slashes. The trail descends. Note: This route description applies to hikers who followed the detour to Pine Mountain’s first knob. Otherwise, see mileage cue 3.0.

3.0Rejoin the Hoop Hole Trail in a saddle between Pine Mountain’s first and second knobs. Hike straight on the Hoop Hole Trail along the top of the ridge as it climbs toward Pine Mountain’s second knob.

3.5Shale rock outcrops on the right mark the approach of Pine Mountain’s second knob (3,038 feet). This stretch of trail is enveloped in waist-high berry bushes and mountain laurel.

3.8Climb out of the gap between Pine Mountain’s second and third knobs. Hoop Hole Trail stays left of the ridgetop.

4.1Climb on Hoop Hole Trail to the spine of Pine Mountain. In a few hundred yards, reach a campsite. From this spot, Hoop Hole Trail drops gradually off the left side of Pine Mountain. Note: Another unmarked trail leads from this campsite up the spine of Pine Mountain and tops out on Rich Patch Mountain.

4.4A mass of boulders marks the rocky joint of the Pine Mountain ridge and Rich Patch Mountain. Follow Hoop Hole Trail as it turns left and threads a gap between Rich Patch Mountain and Bald Knob.

5.7Cross the headwaters of Hipes Branch.

6.4Turn left at a T junction and follow Hoop Hole Trail. Note: A right turn at this T junction leads to parking on VA 615.

6.7At a fork in the trail, bear left onto the yellow-blazed Hoop Hole Trail. Note: Bearing right at this fork leads to parking on VA 615.

8.0Turn right onto Iron Ore Trail.

9.1After descending along a section of trail with steep banks and a trough-like appearance, Iron Ore Trail bears right. Look straight into the woods for an ill-defined footpath marked with faint yellow-painted blazes. It descends to a power line cut in 0.1 mile. Follow the power line easement downhill to a T junction with a dirt road. Turn left onto this dirt road and, in 0.1 mile, turn left onto the Iron Ore Trail.

10.0Hike ends at the trail board near the restrooms at Roaring Run Furnace.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Clifton Forge is a quaint, small town with several restaurants, shops and B&Bs. www.visitcliftonforgeva.com

Roanoke is the closest large city, with lots of visitor amenities. Roanoke Valley Convention & Visitors Bureau, (540) 342-6025, www.visitroanokeva.com

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

Alleghany Highlands Heritage Day & C&O Railway Heritage Festival is held in June in Clifton Forge. www.visitcliftonforgeva.com/heritage-day

LODGING

Firmstone Manor in Irondale, was, appropriately for this hike, built by the ironmaster of the Irondale Furnace Company. (800) 474-9882, www.firmstonemanor.com

From Clifton Forge, drive west on I-64 to the Low Moor exit. Drive south on VA 696 and, in 0.1 mile, turn left onto VA 616. Drive 5.7 miles, then turn left onto VA 621 at Rich Patch Union Church. In 3.3 miles, turn right into the Roaring Run National Recreation Area. GPS: N37 42.400′ / W79 53.594′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 52, C3.

From Clifton Forge, drive west on I-64 to the Low Moor exit. Drive south on VA 696 and, in 0.1 mile, turn left onto VA 616. Drive 5.7 miles, then turn left onto VA 621 at Rich Patch Union Church. In 3.3 miles, turn right into the Roaring Run National Recreation Area. GPS: N37 42.400′ / W79 53.594′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 52, C3.