28. ST. MARY’S WILDERNESS

WHY GO?

There are two types of Virginia hikers: those who have visited St. Mary’s Wilderness and those who soon will; more people visit this 10,000-acre plot of protected wild land on the western slope of the Blue Ridge than any other Virginia wilderness. Easy access to the premier attraction, St. Mary’s Falls, ensures this won’t change any time soon. And a beauty this waterfall is—a wide, 15-foot drop into a deep, narrow gorge replete with massive river boulders and mountain laurel. Beauty of a subtler nature lies deeper into the wilderness. Take the time to explore a bit farther.

THE RUNDOWN

Start: Gravel parking lot opposite Fork Mountain Overlook, milepost 23 on the Blue Ridge Parkway

Distance: 10.6-mile loop

Hiking time: About 7 hours

Difficulty: Moderate due to the hike length and the steep grades along Mine Bank Creek

Trail surface: Dirt roads and footpaths traverse steep mountain slopes, upland meadows, and waterfalls.

Land status: National forest and wilderness area

Nearest town: Steeles Tavern, VA

Other trail users: Cross-country skiers and hunters (in season)

Accessibility: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs permitted

Trail contact: Glenwood-Pedlar Ranger District, Natural Bridge Station; (540) 291-2188; www.fs.usda.gov/gwj

Schedule: Open year-round

Fees/permits: None

Facilities/features: None

NatGeo TOPO! maps: Big Levels, Vesuvius

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Lexington, Blue Ridge Mts

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From Steeles Tavern, drive east on VA 56. In the town of Vesuvius, the road turns left, crosses railroad tracks, and continues east. After a long stretch of winding road and switchbacks, VA 56 junctions with the Blue Ridge Parkway 5.6 miles from Steeles Tavern. Proceed north on the Blue Ridge Parkway for 3.8 miles. At the Fork Mountain Overlook (milepost 23), turn left into a gravel parking lot. There is room for eight to ten cars. GPS: N37 54.682′ / W79 05.202′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 54, A2.

From Steeles Tavern, drive east on VA 56. In the town of Vesuvius, the road turns left, crosses railroad tracks, and continues east. After a long stretch of winding road and switchbacks, VA 56 junctions with the Blue Ridge Parkway 5.6 miles from Steeles Tavern. Proceed north on the Blue Ridge Parkway for 3.8 miles. At the Fork Mountain Overlook (milepost 23), turn left into a gravel parking lot. There is room for eight to ten cars. GPS: N37 54.682′ / W79 05.202′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 54, A2.

THE HIKE

People visit St. Mary’s Wilderness for one overriding reason: waterfalls. The largest, on St. Mary’s River, impresses not so much with height as with width and power. Farther upstream, smaller cascades await in the mountain gullies that feed the river. In these sheltered coves, rock and water interact in subtler ways, as on Mine Bank Branch, where the stream glistens and shines as it tumbles down step-falls. It’s a small reminder why the path less traveled can sometimes be the most rewarding.

The hunt for waterfalls leads farther up into the wilderness. Small streams run off Mine Bank Mountain, Bald Knob, Big Levels, and Cellar Mountain. On them, cascades of varying shapes and sizes spill water en route to St. Mary’s River. There are 20-foot drops into small pools on Sugartree Branch. On Mine Branch, water rolls down like a slinky down the streambed. Small as they appear, each stream contributes volumes of water to St. Mary’s River, which changes from a meandering stream near its headwaters into the frothing, churning powerhouse at St. Mary’s Falls.

In late spring, the rash of mountain laurel blossoms along Mine Bank Branch serves as a timely reminder that waterfalls aren’t the only attraction here. For a few days, the landscape looks as if a late-season snowstorm hit. The dusting ofpink and white fills folds and faults where the stream cuts steeply through bedrock, as if Tinkerbell had brushed hills with a pixie dust. This is the Appalachian wake-up call that marks the end of spring blooms; mountain laurel is the last to flower, after the redbuds, apple blossoms, and dogwoods have shown their stuff.

The sheer volume of mountain laurel makes one consider how this tree reproduces. Stamens on the flower act like a spring. When triggered by bees, the pod-like fruit opens, the anther is released, and oblong pollen beads shake out. Leave the laurel’s honey to the bees, though; if ingested, it’ll cause cramps and chills—even vomiting in extreme cases.

Not to be outdone by the rush of pink and white laurel, June-blooming rhododendron adds its color a month later. Along the fire road that links Green Pond to the Bald Mountain Trail, pink blossoms are abundant. Lore has it that rhododendron hid the moonshiner’s still. Growth is so dense, so high, and seemingly impenetrable, it’s quite possible to pass within a yard or so of someone—or something—and never know it. The tree’s spindly hardwood trunk is unyielding. Not surprisingly, rhododendron and laurel wood have never amounted to much commercially, outside of use in making briar pipes, a tobacco pipe shaped from the root burls, or knots, of heath plants. Manufacturers favored the burl—the hard, dense knots found on roots of these trees—for shaping the bowl of the pipes because it burned slowly.

In late July, mountain laurel and rhododendron flowers give way to the blueberry—the über-berry of its class. Trapped inside these little blue bombers are enough cancer-fighting antioxidants to rank the small blueberry number one among fruits and vegetables in this category. Health benefits don’t stop there, either. Anthocyanin, a chemical that gives berries their blue color, is said to ease eyestrain and improve circulation. Other studies suggest blueberries may even slow the aging process, reason enough to toss another handful into your mouth.

Health is an appropriate subject to consider in light of the threats that face St. Mary’s Wilderness. Here, direct human activity has only the slightest impact. Even scars from mining activity as recently as the 1950s fade as grass and trees overgrow the old railroad grades and mine camps. More insidious is acid rain, which has raised pH levels in St. Mary’s River to a point where native brook trout are suffering—to say nothing of such small aquatic life-forms as salamanders and frogs. The issue put the Forest Service in a quandary: Wilderness areas, by their very definition, are exempt from the tinkering of forest rangers and land managers. These areas are meant to return to nature in whatever form that takes. There is an exception to this rule, however. In cases of fire, insect infestation, or disease, the Forest Service can intervene, as it has since done in St. Mary’s. If one considers acid precipitation a disease, then liming the river (lime is a natural base that counterbalances the acid) is justified. Thus, in the past 20 years the Forest Service has limed the river three times—in 1999, 2005, and 2013—and native brook trout populations in the river have rebounded, to the great satisfaction of anglers who treasure the river as much as hikers.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

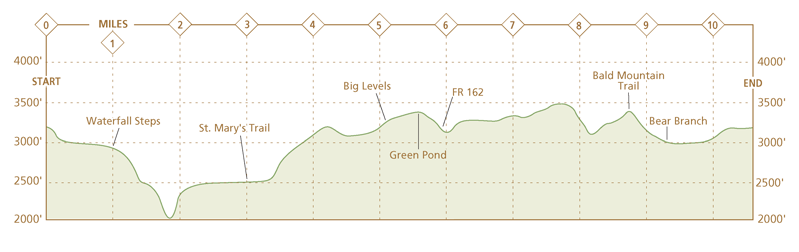

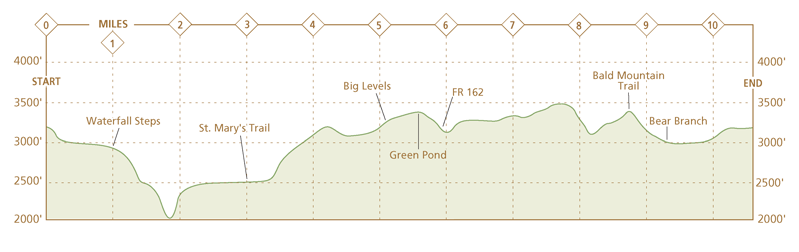

0.0Start from a trail sign for the Mine Bank Trail on the wooded side of the gravel parking lot. A few feet after starting the hike, turn left and follow the orange blazes of Mine Bank Trail. The Bald Mountain Trail that turns right at this junction is the return portion of this hike.

0.3The trail switches back several times as it drops down the side of Mine Bank Mountain. The trail surface is loose pebbles. In fall, the views soar across the river valley below to Cellar Mountain.

0.5After a steep descent, reach the headwaters of Mine Bank Branch. The trail bears left and descends with the stream to the right. Mountain laurel and rhododendron are plentiful here.

1.0Cross the stream to the right bank. As you cross, the stream drops 20 feet or so on a series of steps cut into the bedrock. The trail descends steeply with the stream on the left.

1.3Cross back to the left stream bank. The trail continues to descend past rock outcrops on the left hillside. Take time to cut through the woods on the right for wonderful photo ops of the stream’s many small waterfalls.

2.1Mine Bank Branch takes the first of two steep plunges off the mountain slope. The trail, which has descended at a moderate rate, steepens at each waterfall.

2.6The trail and stream part ways, with Mine Bank Trail arcing left through the oak-hardwood forest. Note: In spring, this is a muddy stretch of trail.

3.0Turn right onto blue-blazed St. Mary’s Trail. Follow St. Mary’s River upstream. Side trip: St. Mary’s Trail to the left leads 2.3 miles to the St. Mary’s Falls Trail. The trail passes first through an old mine operation and, farther downstream, rugged Sugartree Hollow. St. Mary’s Falls Trail is a 0.5-mile hike to the 15-foot St. Mary’s Falls. This detour adds 5.6 miles and several hours to this loop hike.

3.2Cross Bear Branch as it enters from the right. Follow St. Mary’s Trail upstream. Option: To shorten your trip, you can turn right onto the unmarked Bear Branch Trail as it follows Bear Branch for a return to the Bald Mountain Trail. This bushwhack requires you to follow the Bear Branch stream bank for about a mile, after which an old road leads another mile to Bald Mountain Trail.

3.3Signs of old iron ore mining operations are visible off the trail. Dirt mounds cover rusted buckets, and an inspection of the tall grassy areas reveal twisted pieces of metal and concrete footings. The trail passes through some shallow mining pits and reenters the woods.

4.0After crossing a much diminished St. Mary’s River several times, the trail begins climbing on an old road. Several times, it dips into the woods for switchbacks to aid the steep ascent.

5.1Enter Big Levels, a mountain plateau. Continue straight on St. Mary’s Trail.

5.6Reach Green Pond. Pass to the left of the pond. Note: Green Pond is a “pond” in name only. It dries up in drought conditions and should not be considered a reliable source of water.

5.9Turn right onto FR 162. This wide dirt and gravel road with no markings climbs Bald Knob on switchbacks.

7.1FR 162 levels as it crosses Flint Mountain.

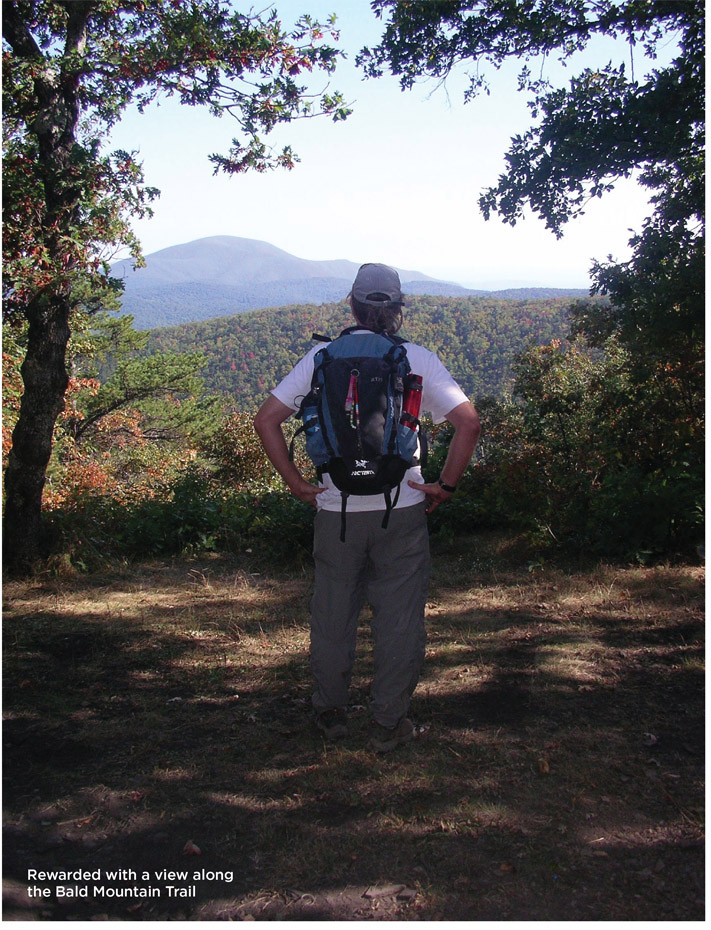

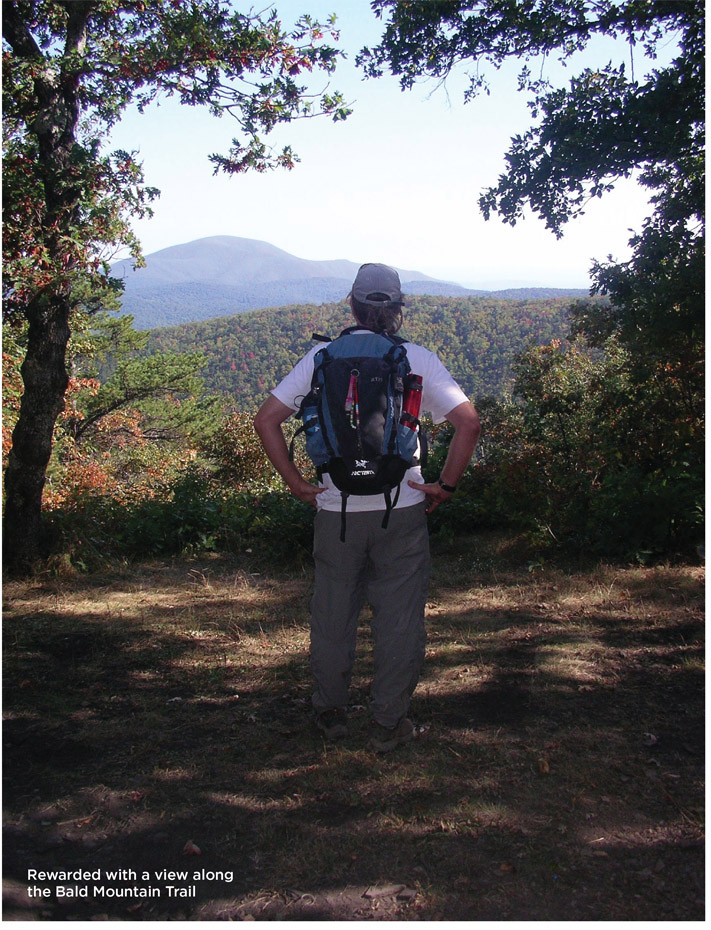

7.4Views open on the left side of the trail. Torry Ridge is visible to the north. To the east, Three Ridges looms beyond the Blue Ridge Parkway. The trail arcs southwest and climbs at a more gradual pace.

8.8Turn right onto the yellow-blazed Bald Mountain Trail. Look for a wilderness boundary sign on the right as a guide mark. The trail drops down the slope through a young hardwood forest.

9.3Continue straight past an unmarked road that descends downhill on the right. This is the upper end of the Bear Branch bushwhack.

9.6Cross a small stream on a three-log bridge amid heavy growth of mountain laurel, and rhododendron, with only a few majestic hemlock trees that have survived the woolly adelgid blight.

9.8The trail arcs left and the climb, which has been gradual the last half-mile, steepens.

10.2Cross several earthen embankments intended to block vehicle traffic on the trail, which is now an old roadway. There are campsites in this area.

10.5Turn right onto a narrow footpath and walk several hundred yards to a junction with Mine Bank Trail.

10.6Turn left onto Mine Bank Trail and arrive back at the gravel parking lot.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Staunton Convention & Visitors Bureau, Staunton, (540) 332-3865, www.visitstaunton.com

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

Woodrow Wilson Birthplace & Museum, 24 N. Coalter St., Staunton; (540) 885-0897, www.woodrowwilson.org

The Cyrus McCormick Farm & Workshop, Raphine, (540) 377-2255, www.arec.vaes.vt.edu/shenandoah-valley. Site where McCormick invented the first mechanical reaper, with a blacksmith shop, gristmill, and museum. The annual McCormick Farm Mill Day is held in Oct.

ORGANIZATIONS

The Virginia Wilderness Committee has trail information and a downloadable map of St. Mary’s Wilderness at www.vawilderness.org/st-marys-wilderness.html.

Wilderness Connect, www.wilderness.net, also has good information on the nation’s wilderness areas.

Tidewater Appalachian Trail Club, Norfolk, www.tidewateratc.com. Maintains trails in the St. Mary’s Wilderness.

From Steeles Tavern, drive east on VA 56. In the town of Vesuvius, the road turns left, crosses railroad tracks, and continues east. After a long stretch of winding road and switchbacks, VA 56 junctions with the Blue Ridge Parkway 5.6 miles from Steeles Tavern. Proceed north on the Blue Ridge Parkway for 3.8 miles. At the Fork Mountain Overlook (milepost 23), turn left into a gravel parking lot. There is room for eight to ten cars. GPS: N37 54.682′ / W79 05.202′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 54, A2.

From Steeles Tavern, drive east on VA 56. In the town of Vesuvius, the road turns left, crosses railroad tracks, and continues east. After a long stretch of winding road and switchbacks, VA 56 junctions with the Blue Ridge Parkway 5.6 miles from Steeles Tavern. Proceed north on the Blue Ridge Parkway for 3.8 miles. At the Fork Mountain Overlook (milepost 23), turn left into a gravel parking lot. There is room for eight to ten cars. GPS: N37 54.682′ / W79 05.202′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 54, A2.