31. HUCKLEBERRY LOOP

WHY GO?

Two of Virginia’s long trails, the Appalachian Trail and the Allegheny Trail, pass through Peters Mountain Wilderness, a patch of forestland on the steep ridge that constitutes the Virginia-West Virginia border. But neither well-traveled trail quite captures what it means for a forest to turn wild as well as the Huckleberry Loop. The trail down Dismal Branch on the eastern slope of Peters Mountain is as rough as they come, overrun with rhododendron, blocked by blowdowns, and often lost altogether in the streambed. There are car-size boulders en route, and rotted logs litter the creek bed. This trail sums up everything a wilderness should be: beautiful, difficult, and, in the end, extremely satisfying.

THE RUNDOWN

Start: Dirt road off VA 722/Glen Alton Drive

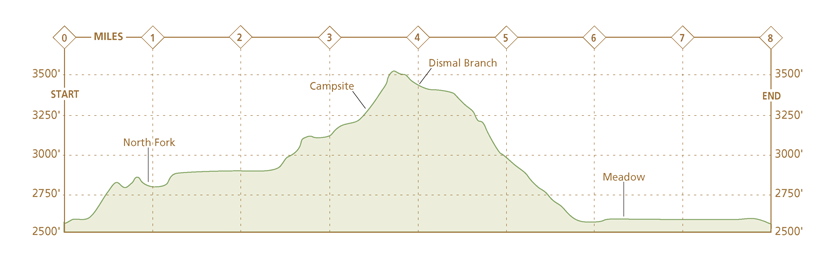

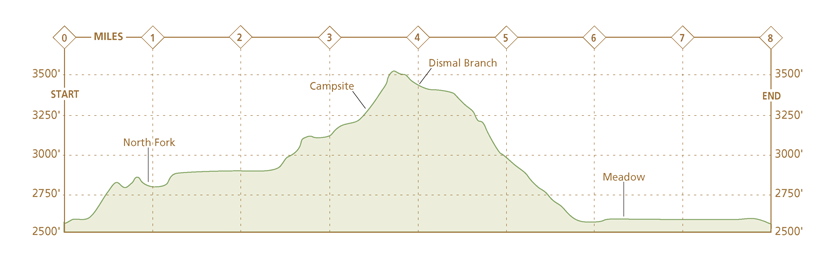

Distance: 8.0-mile loop

Hiking time: About 4 hours

Difficulty: Moderate due to easy hiking on clearly marked, well-graded trails, with one very difficult stretch down Dismal Branch

Trail surface: Dirt woods paths and dirt roads lead through hardwood forest slopes, fields, a river valley, and streambed.

Land status: National forest

Nearest town: Pembroke, VA

Other trail users: Hunters (in season)

Accessibility: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs permitted

Trail contact: Eastern Divide Ranger District, Blacksburg; (540) 552-4641; www.fs.usda.gov/gwj

Schedule: Open year-round. Hunting is permitted in national forests, with Nov through Jan the busiest season.

Fees/permits: None

Facilities/features: None

NatGeo TOPO! map: Interior

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Blacksburg, New River Valley; Covington, Alleghany Highlands; Appalachian Trail, Damascus to Bailey Gap; Appalachian Trail, Bailey Gap to Calf Mountain; New River Blueway

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From Pembroke, drive north on US 460 for 2 miles and turn right onto VA 635. There is good signage for White Rocks NRA and Glen Alton. After 5.6 miles, follow VA 635 as it turns left and crosses Stony Creek. Drive another 8.1 miles and turn left onto gravel VA 722/Glen Alton Drive. Immediately cross Stony Creek and, in 0.2 mile, turn left onto Kelly Flats Road. In 0.1 mile, there will be a forest gate that may only be open during hunting season. Park here (do not block road) and walk 0.4 mile to the trailhead. GPS: N37 25.597′ / W80 33.331′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 41, A5.

From Pembroke, drive north on US 460 for 2 miles and turn right onto VA 635. There is good signage for White Rocks NRA and Glen Alton. After 5.6 miles, follow VA 635 as it turns left and crosses Stony Creek. Drive another 8.1 miles and turn left onto gravel VA 722/Glen Alton Drive. Immediately cross Stony Creek and, in 0.2 mile, turn left onto Kelly Flats Road. In 0.1 mile, there will be a forest gate that may only be open during hunting season. Park here (do not block road) and walk 0.4 mile to the trailhead. GPS: N37 25.597′ / W80 33.331′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 41, A5.

THE HIKE

Dismal Branch runs a noisy route for 3 miles down the slope of Peters Mountain. In a gully between Pine Swamp Ridge and Huckleberry Ridge, a series of obstacles force stream and hiker to detour. A blown-down tree too big to either crawl over or under sends the hiker through rhododendron so dense it requires pushing back thickets with both arms. At this point, Dismal Branch disappears underground beneath a rock slide. Five paces downhill, this unsinkable stream spurts from beneath the rocks and runs around a huge boulder. The stream disappears beneath rocks once more, then returns to the surface to spill off a small rock cleft into a pool. So calm is this pool, so calm is the water, it’s almost as if the stream is making a statement: “See, that wasn’t so hard, was it?”

Huckleberry Loop, an 8-mile trail through Peters Mountain Wilderness and pastoral Kelly Flats, cannot be judged by one difficult stretch of trail. But it’s a fact: Memories of Dismal Branch will stay with a hiker long after sweet-smelling hemlocks along Dixon Creek and the quiet solitude of the North Fork fade. The reason is simple. Dismal Branch captures the essence of wilderness in Virginia, a place where plants and land are free to take whatever shape nature deems appropriate.

Virginia’s forestland is, by and large, comprised of second- and third-generation trees. Axes, crosscut saws, plows, shovels, dynamite, fire, even the hands of the herb and mushroom collector—all have reshaped the land, plants, and trees. Clear-cutting of Virginia forests reached a peak between 1890 and 1920, when nearly every usable tree was cut and shipped to the sawmill. There’s a rusted railroad car wheel lying in the brush alongside the North Fork, evidence of this area’s logging past. The wide, flat terrain along the stream was the grade on which railroad cars ran, loaded with wood. Few areas escaped the clear-cutting. Where old-growth timber stands, it’s as much thanks to chance as any intent to preserve the trees.

Despite all this, forests are adaptable. Left unchecked, climax species, or the last succession of a mature forest, will return on land clear-cut for lumber. On Peters Mountain, oak and hickory will someday stand tall. (Efforts are ongoing, but it’s debatable whether chestnut, once a dominant tree of the Southern Appalachians, will ever return. A blight, Cryphonectria parasitica, attacks the chestnut in its infancy. The tree, which once towered 100 feet high, may grow head-height before succumbing.) At lower elevations, nature has a head start on 40 acres near Dixon Branch. Here you’ll find a stand of old-growth eastern hemlocks, a climax tree that normally requires generations to reach its peak growth. It took hundreds of years to reach the breadth of those that stand along Dixon Branch—a staggering thought, given the timber industry’s penchant to shear mountaintops of all usable lumber.

Forest recovery begins in the forest understory, where competition for sunlight and water is stiff among the many small trees and shrubs. Hardly the stars of any forest, spicebush, witch hazel, black haw, and maple leaf viburnum fill an important niche. Fox, grouse, and pheasant eat the fruit, bark, and leaves of these trees. White-tailed deer will tug on clusters of blackish-blue berries on the black haw, or nibble the bark off a mountain maple sapling. Huckleberry Ridge and neighboring Peters Mountain are home to a population of black bear, and the blueberry and huckleberry patches that cover higher slopes are a primary food source for this animal. Heath-type shrubs, especially, are dynamos. A huckleberry (a bit darker in the bark than the blueberry and peppered with telltale yellow resin spots on the leaves) has ten seeds per berry. Its cousin, the blueberry, has more than one hundred seeds in each blue ball.

A half-mile into this loop, where the trail turns off a gravel road and rises on a gentle shoulder of Locust Knob, shrubby plants gobble up the dry, leafy forest real estate. It stands in stark contrast to the shaded, moist terrain along Dixon Branch and, especially, Dismal Branch, both of which lie ahead. On these dry slopes, mountain laurel and rhododendron are conspicuously absent. You’ll see young chestnut oak and maple trees, flowering dogwood with its characteristic white blossom in springtime, and sassafras, a curious tree with three distinctly different leaves. Along Dixon and Dismal Branches, by comparison, the moist ground supports a habitat marked by slicks of rhododendron, mosses, and ferns. Taller still are the hemlock, tulip poplar, sweet buckeye, and, most beautiful in spring, mountain silverbell. As different as these two environments appear, both are less than 100 years recovered from logging.

Sassafras is one clue to a forest’s ongoing recovery, and the small tree is plentiful in this area. Sassafras’s three leaves are distinct: one oblong, one shaped like a mitten, the other lobed in the center. During spring and summer, a hiker is likely to brush past one without a second notice. In fall, however, the tree’s brilliant red foliage catches your attention; sassafras is one of the showier autumn plants in southern forests. Safrole, a clear oil extracted from the bark, was once used to flavor root beer, teas, and stews. (In the 1960s, safrole was shown to cause cancer in mice in laboratory experiments. The FDA banned use of the oil in foodstuffs.) I can’t help but pass along, however, that boiling the leaves and twigs for tea produces an intense buzz. I now know that it’s sassafras roots—not twigs and leaves—that have for years flavored teas and root beer. But when you’ve forgotten your edible plant book and you’re feeling adventurous, strange things happen.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start at the red Forest Service gate on VA 722. The Huckleberry Loop Trail follows VA 722 for 0.4 mile and is blazed with single yellow triangles nailed on trees on the left side of the road.

0.4Turn right off the gravel road onto a well-blazed narrow woods path through chestnut oak and maple. A small yellow and brown sign with a hiker symbol marks this turnoff.

0.9Thick stands of rhododendron line the descent to the North Fork, where you’ll turn left and hike upstream, climb a short hill, then drop to the river’s edge to cross.

1.1Cross the North Fork and hike up the right side of the stream on a flat, narrow woods path. Small hemlocks and rhododendron separate the trail and stream. Up the slope to the right of the trail is a young hardwood forest. Mayapple grows along the path, and rotting logs and trees host a variety of coral and trumpet mushrooms. Note: This trail used to be called Flat Peter—a hybrid of Kelly Flats and Peters Mountain—and some brochures and books still refer to it by that name.

1.9Pass by an unblazed trail that branches right off Huckleberry Loop Trail. In a few yards, pass rusted pieces of a railcar in the underbrush on the right side of the trail.

2.0Pass over the North Fork on a wooden footbridge. There is a nice stream-side campsite on the opposite bank. Bear left out of the campsite, follow Dixon Branch upstream a few feet and cross it on three moss-coated logs. The trail now follows Dixon Branch up the north side of Huckleberry Ridge to a saddle between the ridge and Peters Mountain. The route is lined with hemlocks and rhododendron. Numerous stream crossings make for a wet hike during the spring.

3.4Reach a campsite on Dixon Branch just before your seventh stream crossing. On the other side, trail conditions deteriorate steadily. Logs block the trail and stretches of the path are very rocky. The next half-mile brings four more stream crossings.

4.0As the trail approaches the headwaters of Dismal Branch, it passes through a fern glade and a tall canopy forest dominated by tulip poplar. After a stretch of trail overgrown with mountain laurel and berry bushes, you’ll reach Dismal Branch and turn southeast to travel downstream past a nice campsite with a fire ring.

4.7A massive blowdown forces you off the trail and into the creek bed. Here, the stream runs through narrow channels formed by car-size boulders, then under a rock slide. It’s audible, but you can’t see it. The next 0.5 mile brings numerous stream crossings. At points, the trail and stream run the same course.

5.9Exit Peters Mountain Wilderness. The trail, which has slowly changed from torturous, rocky streambed to wide, grassy road, turns left to return through the fields of Kelly Flats, a series of old fields flanked by Huckleberry and Sarton Ridges.

6.3Enter a clearing bordered by plantations of white pines and wide-open fields of grass, milkweed, and other weeds. The trail follows a rutted road along the upper edges of the meadow.

8.0Reach a forest gate, pass through, and turn left onto a gravel road. The parking area is a few short feet uphill.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Visit Giles County, Pearisburg, (540) 921-2079 www.virginiasmtnplayground.com

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

The New River Water Trail traverses 37 miles through Giles County, www.newriverwatertrail.com.

LODGING

Nesselrod on the New River, Radford, (540) 731-4970, www.nesselrod.com. A B&B on the cliffs overlooking the New River.

White Rocks National Recreation Area Campground, Giles County, (540) 552-4641

Claytor Lake State Park, Montgomery County, (540) 643-2500, www.dcr.Virginia.gov/state-parks/claytor-lake. Cabins and camping are available.

From Pembroke, drive north on US 460 for 2 miles and turn right onto VA 635. There is good signage for White Rocks NRA and Glen Alton. After 5.6 miles, follow VA 635 as it turns left and crosses Stony Creek. Drive another 8.1 miles and turn left onto gravel VA 722/Glen Alton Drive. Immediately cross Stony Creek and, in 0.2 mile, turn left onto Kelly Flats Road. In 0.1 mile, there will be a forest gate that may only be open during hunting season. Park here (do not block road) and walk 0.4 mile to the trailhead. GPS: N37 25.597′ / W80 33.331′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 41, A5.

From Pembroke, drive north on US 460 for 2 miles and turn right onto VA 635. There is good signage for White Rocks NRA and Glen Alton. After 5.6 miles, follow VA 635 as it turns left and crosses Stony Creek. Drive another 8.1 miles and turn left onto gravel VA 722/Glen Alton Drive. Immediately cross Stony Creek and, in 0.2 mile, turn left onto Kelly Flats Road. In 0.1 mile, there will be a forest gate that may only be open during hunting season. Park here (do not block road) and walk 0.4 mile to the trailhead. GPS: N37 25.597′ / W80 33.331′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 41, A5.