33. CRAWFISH/CHANNEL ROCK

WHY GO?

Originating in the flat bottomland and old fields of Crawfish Valley, the Crawfish/Channel Rock Trail ascends Brushy Mountain on steep, narrow footpaths to run northeast parallel to Walker Mountain. En route, you’ll cross the Tennessee Valley Divide, where Reed Creek and Bear Creek vividly illustrate the effects of the divide. Flowing off opposite sides of the divide, each enters separate, ever-expanding stream networks that eventually reach the Ohio River, albeit 100 miles distant from one another. Deer and raccoons forage along the stream edges; turkeys and ruffed grouse hunt for acorns on the slopes of Brushy and Walker Mountains. Beavers leave the most lasting impression: a two-stage dam you’ll traverse on Bear Creek.

THE RUNDOWN

Start: Parking area at the dead end of FR 727 (Strawberry Road). As you enter the parking area, the trailhead is on a dirt road on the right.

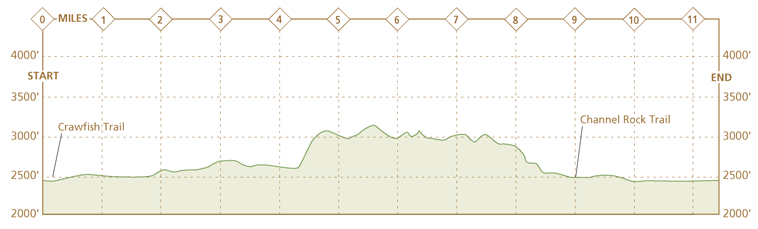

Distance: 11.2-mile lollipop

Hiking time: About 6 hours

Difficulty: Moderate due to several steep climbs up Brushy Mountain

Trail surface: Dirt forest road and singletrack woods paths wind through stream valleys and old fields, along dry ridgetops, and up steep climbs.

Land status: National forest

Nearest town: Rural Retreat, VA

Other trail users: Mountain bikers, equestrians, and hunters (in season)

Accessibility: None

Canine compatibility: Dogs permitted

Trail contact: Eastern Divide Ranger District, Blacksburg, (540) 552-4641, www.fs.usda.gov/gwj

Schedule: Open year-round. Hunting is allowed in national forests, with the busiest season Nov through early Jan.

Fees/permits: None

Facilities/features: None

NatGeo TOPO! map: Rural Retreat

NatGeo Trails Illustrated map: Mount Rogers National Recreation Area; Blacksburg, New River Valley; New River Blueway

FINDING THE TRAILHEAD

From Rural Retreat, drive north on VA 90 to Staley Crossroads, where the route north becomes VA 680. (If traveling on I-81, take exit 60 [Rural Retreat] and turn left on VA 680, 1.3 miles north of Rural Retreat). Take VA 680 for 2.6 miles, turn left onto VA 625, and follow it 4.2 miles to a fork in the road. Bear left onto FR 727 which is signed as Strawberry Road, a one-lane gravel road. Drive 1.8 miles and reach a large, circular turnaround area and parking for the trail. GPS: N36 57.916′ / W81 18.916′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 23, A6.

From Rural Retreat, drive north on VA 90 to Staley Crossroads, where the route north becomes VA 680. (If traveling on I-81, take exit 60 [Rural Retreat] and turn left on VA 680, 1.3 miles north of Rural Retreat). Take VA 680 for 2.6 miles, turn left onto VA 625, and follow it 4.2 miles to a fork in the road. Bear left onto FR 727 which is signed as Strawberry Road, a one-lane gravel road. Drive 1.8 miles and reach a large, circular turnaround area and parking for the trail. GPS: N36 57.916′ / W81 18.916′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 23, A6.

THE HIKE

Traveling with surveyors into Cherokee Indian territory, 18th-century botanist William Bartram recorded a memorable scene while encamped northwest of Big Lick, Georgia: In a mountain stream, below a set of minor rapids, gold darters swarmed around small mounds made of rock and mud below the water surface. Periodically, crayfish rushed forth from the towers, “at which time a brilliant fight presented; the little gold-fish instantly fled from every side, darting through the transparent waters like streams of lightning,” Bartram wrote.

Crayfish, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mud bugs—call them what you will, they’re a fascinating part of a forest stream’s ecology. The battle with “gold-fish” described by Bartram in his Travels, published in 1791, is a reminder of the surprisingly vicious underworld they inhabit. In a mountain stream, small fish regularly prey on one another. Around rock ledges near a creek’s headwaters, chubs cannibalize their young. Trout circle in riffling water searching for lunch. A crayfish, sensing danger, flicks up a cloud of silt and scuttles backward under a rock. When a predator approaches, schooling fish draw into a tight pack and flee upon sensing a chemical alarm emitted by one of their own. Tadpoles, too, scatter with a telltale odor. The alarmer, in doing so, cannot escape and sacrifices itself.

There’s no guarantee that Reed Creek, a stocked trout stream running down Crawfish Valley between the steep slopes of Brushy and Walker Mountains, will yield the same battle royal Bartram observed. You’ll see plenty of crawfish and their mud-and-rock mounds in the stream. It’s these that make Reed Creek and Bear Creek—the two streams that define the lower elevations of this loop hike—great theater. By midsummer, the water level has dropped from spring highs, leaving isolated pools. Here, a myriad of life-forms—darters and shiners, crayfish, salamanders, and water bugs—play out their busy, and in some cases, very short lives.

Along stretches of these creeks, especially through Channel Rock Hollow, larger hemlock trees draw nourishment from the stream. This evergreen splits and crumbles rocks with a tenacious root grip, contributing over time to a buildup of sediment in the small pools where the stream rests between cascades. Tennessee dace, a tiny fish with markings from olive to scarlet red, inhabit pools like this in Bear Creek. The dace is threatened; the only other community is on the Lick Creek in Bland County.

Easier to spot are the darts that return to the same pool in which they were born to lay eggs. Once it establishes residency, a fish will rarely venture from the area during spawning. One theory on the how and why of their return links the fish and the shoreline trees in a symbiotic relationship. Tree roots release organic molecules into the water and the fish may use the chemical as a homing signal.

Rising from the stream, the bottomlands in Crawfish Valley exhibit various stages of old-field succession. For 2 miles from the trailhead, fields drop gently left of the dirt road trail, reaching a fringe of trees that camouflage the stream. Ragweed grew tall the first year after the fields were abandoned. When it decomposes, this weed (the bane of hay fever sufferers) poisons the soil. Each subsequent year, the plant grows smaller and smaller until the stunted bunches of stalks, visible here, are all that remains. Queen Anne’s lace with its telltale red spot—in folklore, a drop of Queen Anne’s blood—sways on tall stalks. The flower is a member of the parsley family, with a tuber-like root resembling the carrot—it’s also known as the wild carrot. Dig up the root in the autumn and it’s the best carrot you’ve ever eaten. Beware, however: The plant looks similar to the water hemlock, an extremely poisonous (though tough to find) plant.

Along Bear Creek, the process of old-field succession is more advanced. This stream runs off the southwest side of the Tennessee Valley Divide. Skinny hardwoods and thickets of rhododendron grow alongside the stream. Poplar and its varieties, big tooth aspen and quaking aspen, are encroaching, step by step, on the old fields beyond the riverbanks. These hardwoods, disdained by lumber companies that wanted the harder chestnut and oaks, are pioneer species in the woody stage of old-field succession. Their tough seedlings can bear the exposure to sun and other elements that climax trees such as oak, hickory, or hemlock that typify a mature forest, cannot. The pioneer trees reach top potential growth in 50 to 60 years, in the process creating the forest canopy that allows climax tree species to grow.

Overgrown fields are just one indicator along this hike that the land here was farmed. If you missed the subtler clues—fruit trees, overgrown fields, barbed wire, cut stone blocks—of past homesteaders, the board tacked onto an oak tree in a clearing near the trail’s junction with the Appalachian Trail (AT) gives it away. The board reads Mozer’s Place, marking the homesite of James Mozer, who farmed the upper reaches of Crawfish Valley at the turn of the last century. Lower in the valley, Simon Foglesong farmed 1,000 acres on Reed Creek in 1790; the family cemetery is on the south side of the stream on national forest land, as are the remnants of the homesite. Between these sites, plots of sorghum, a wild grain, dot the roadside. These are not indicators of someone following in the pioneer’s footsteps. Rather, they’re wildlife plots planted by the state Department of Conservation & Recreation for turkey and small songbirds.

From the valley floor, Brushy Mountain and its foothills frame Crawfish Valley on the east, and Walker Mountain rises to the west. The Wilderness Society calls this region one of the largest roadless areas in the Jefferson National Forest (referring to active forest roads, not the roads-turned-trails that comprise large parts of this loop). This and the presence of the Tennessee dace in lower Bear Creek make it a candidate for wilderness designation. The sense of isolation so often associated with a wilderness area creeps up on you on the steep climb up Brushy Mountain. Berry bushes crowd the narrow trail, scratching at your pant legs. Allegheny chinquapin and chestnut oak grow in the forest understory Views in all directions are blocked by the dense understory of these thin trees. Your footsteps may flush a turkey. These popular game birds awaken the hiker who camps on Brushy Mountain. Before sunrise, the birds call out to one another, a signal to head downslope to the river. And so, too, you rise, pack up your belongings, and head down the final stretch of trail off Brushy Mountain.

MILES AND DIRECTIONS

0.0Start at a brown forest gate across the dirt road leading from the parking lot. Crawfish Trail begins at the forest gate and follows the dirt road as it runs along the base of Walker Mountain amid black-eyed Susans, asters, blackberries, and grasses. Wide fields open up left of the trail, and beyond the fields flows Reed Creek.

1.0Come to a junction of Crawfish Trail and Channel Rock Trail; continue straight. Note: Channel Rock Trail branches left off the road through a field and crosses Reed Creek. This is the return leg of this loop hike.

1.5Pass a good campsite amid pines and tulip poplar.

1.8Pass through a grassy clearing. Crawfish Trail is now a dirt path. Blackberries are abundant in midsummer. Pass another campsite on the right within 0.2 mile.

2.6Pass through a clearing dominated by a single large oak. A board nailed to the tree identifies this as the onetime homesite of James Mozer, a settler who farmed this valley in the early 1900s. Pieces of a home foundation lie in the overgrown grass.

2.8Turn left onto the Crawfish Trail at a T junction with Walker Mountain Trail (Walker Mountain Trail continues straight). This junction is marked by orange arrows tacked onto a tree. A few feet after turning, cross Reed Creek and enter a clearing with a fire ring. From the clearing, turn right and enter the woods under a tunnel of rhododendron. A signboard marks where the white-blazed AT exits the clearing.

3.5The trail passes several fields overgrown with grass. Past the second clearing, turn left and follow Crawfish Trail as it descends downhill into woods. Note: Be alert. This is an unmarked turn in the trail. If you hike more than 0.1 mile without seeing an orange blaze, turn around and search for the turn, which will now be on the right.

3.8Crawfish Trail and Bear Creek briefly run alongside one another amid tall hemlocks. Follow Crawfish Trail as it climbs a grassy road to a clearing. In this clearing, turn left and follow a grassy road downhill. Note: In this clearing, avoid a grassy road that continues uphill. It is marked with yellow blazes.

4.2Reach a beaver dam across Bear Creek. Take a bead on a massive maple tree on the opposite bank and cross the creek. Note: At high water, you will have to hike downstream and cross at a shallow bend in the stream. Return to the large maple tree on the trail. From this tree, walk up the grass road for 100 yards, turn right, and follow the faintly defined road. The trail is obscured by waist-high grass. Bear Creek flows in a deep gully on your right.

4.5Turn left and follow Crawfish Trail as it climbs steeply up Brushy Mountain as a narrow dirt footpath.

5.9Cross the AT and head downhill. The next mile brings more steep climbs along the spine of Brushy Mountain amid a ridge forest of chestnut oak, maple, scrub pines, and berry bushes.

7.8Crawfish Trail steeply drops off the right side of the ridge, descending along the forest boundary marked by red paint slashes. The trail winds up and down the foothills of Brushy Mountain, straddling the forest boundary the entire way.

9.0The trail converts to a grassy road as it descends into a clearing. Several old roads merge here. Avoid roads that are yellow blazed and posted private property. Instead, turn left onto Channel Rock Trail and follow plastic orange blazes downhill past rhododendron.

9.7Reach the first of several points on the trail where Channel Rock Branch merges with the trail. (The stream’s name is clear—the water has eroded a channel through the schist bedrock. Portions of the trail are very wet.)

10.2Cross Reed Creek and rejoin Crawfish Trail. Turn right to return to the parking area.

11.2Hike ends at the forest gate across Crawfish Trail. Walk past the gate to enter the parking area.

HIKE INFORMATION

LOCAL INFORMATION

Wythe Convention & Visitors Bureau, 975 Tazewell St., Wytheville; (877) 347-8307; http://visitwytheville.com

LOCAL EVENTS/ATTRACTIONS

The Settlers Museum of Southwest Virginia, 1322 Rocky Hollow Rd., Atkins; (276) 686-4401; www.settlersmuseum.com. Dedicated to the mountain pioneers of southwest Virginia.

LODGING

Hungry Mother State Park, Smyth County, (276) 781-7400 http://www.dcr.virginia.gov/state-parks/hungry-mother. Cabins and camping are available.

From Rural Retreat, drive north on VA 90 to Staley Crossroads, where the route north becomes VA 680. (If traveling on I-81, take exit 60 [Rural Retreat] and turn left on VA 680, 1.3 miles north of Rural Retreat). Take VA 680 for 2.6 miles, turn left onto VA 625, and follow it 4.2 miles to a fork in the road. Bear left onto FR 727 which is signed as Strawberry Road, a one-lane gravel road. Drive 1.8 miles and reach a large, circular turnaround area and parking for the trail. GPS: N36 57.916′ / W81 18.916′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 23, A6.

From Rural Retreat, drive north on VA 90 to Staley Crossroads, where the route north becomes VA 680. (If traveling on I-81, take exit 60 [Rural Retreat] and turn left on VA 680, 1.3 miles north of Rural Retreat). Take VA 680 for 2.6 miles, turn left onto VA 625, and follow it 4.2 miles to a fork in the road. Bear left onto FR 727 which is signed as Strawberry Road, a one-lane gravel road. Drive 1.8 miles and reach a large, circular turnaround area and parking for the trail. GPS: N36 57.916′ / W81 18.916′. DeLorme: Virginia Atlas & Gazetteer: Page 23, A6.