A person traveling west from the Atlantic Coast would, after 100 miles or so, encounter a significant change in the landscape of Virginia. Around Richmond and Fredericksburg, the topography shifts from the flat lowland of the Coastal Plain to the soft hills of the Piedmont. Along rivers, impressive waterfalls mark this line of demarcation, the spot where resistant Piedmont bedrock gives way to sand and clay. A few miles downstream, the largest waterways cease acting as real rivers and instead become estuaries, filled with brackish water and ruled by the ebb and flow of the ocean’s tide.

Upland from the fall line—which roughly traces I-95—Virginia’s landscape begins a slow march to the Blue Ridge. The term rolling Piedmont borders on cliché, but remains the best description of the landscape, which dips and rises in ever-greater folds, until finally giving way to the mountains of western Virginia.

The landscape wasn’t always so uniform. Piedmont bedrock shows signs of violent prehistoric mountain-building events. Large basins, some miles and miles in length and width, collected mud and silt that eroded from mountains to the west. This same material later, under intense heat and pressure, became Arvonian and Quantico1 slate, considered among the highest quality found worldwide. Today a thick mantle of clay and sediment covers most of the bedrock in the Piedmont. The poverty of exposed rock makes outcrops visible along Holliday Creek in Appomattox-Buckingham State Forest a rewarding experience.

Evidence of Native Americans in Virginia dates from 10,000 years ago. In central Virginia, ancestors of the Monacan Indians traveled and camped along the major rivers. The rise of the powerful Indian confederacies, the Powhatan in Tidewater and the Monacans west of the Blue Ridge, left central Virginia as a buffer between them. Both tribes hunted and traveled in this area, but archaeologists have yet to identify large permanent settlements on the scale that existed elsewhere in the state. Artifacts and stone piles near Willis Mountain point to the region possibly holding ritual or ceremonial significance for prehistoric Indians and their ancestors.

European contact in the 1600s brought the rise of the agricultural machine in the central Piedmont. Planters grew tobacco. Bateaux laden with tobacco hogsheads, livestock, and grains plied shallow streams such as the Willis and Slate Rivers. With advances in technology came the large-scale mining of gold, iron ore, coal, slate, and other minerals.

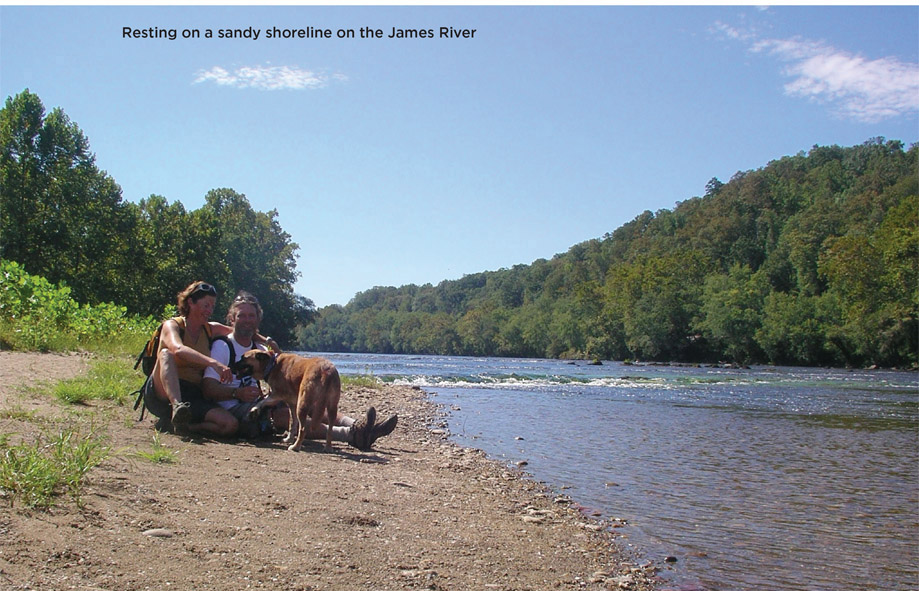

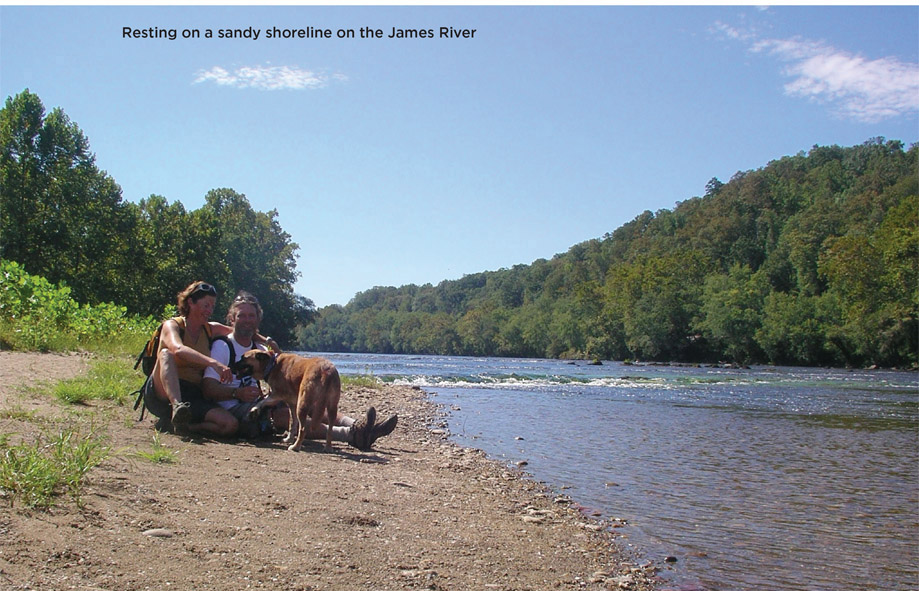

Today those rivers that were the lifeblood of central Virginia commerce serve as natural hiking corridors. Grass and weed-choked floodplains give way to hillsides covered with mountain laurel. And where the landscape levels into fields, Virginia pine and black oaks dominate. Yet, due to this history of heavy farming, the overarching feature of central Virginia remains its wide-open landscape, a holdover from days when farmers planted acre after acre of tobacco until the soil failed, only to move west in search of fresh land. State forests created in the 1920s and 1930s have slowly rehabilitated depleted land by managing the growth of timber for commercial use. For people who enjoy the outdoors, this commercial-driven enterprise has a fortunate by-product: pockets of forest that offer quality recreation opportunities.

THE HIKES

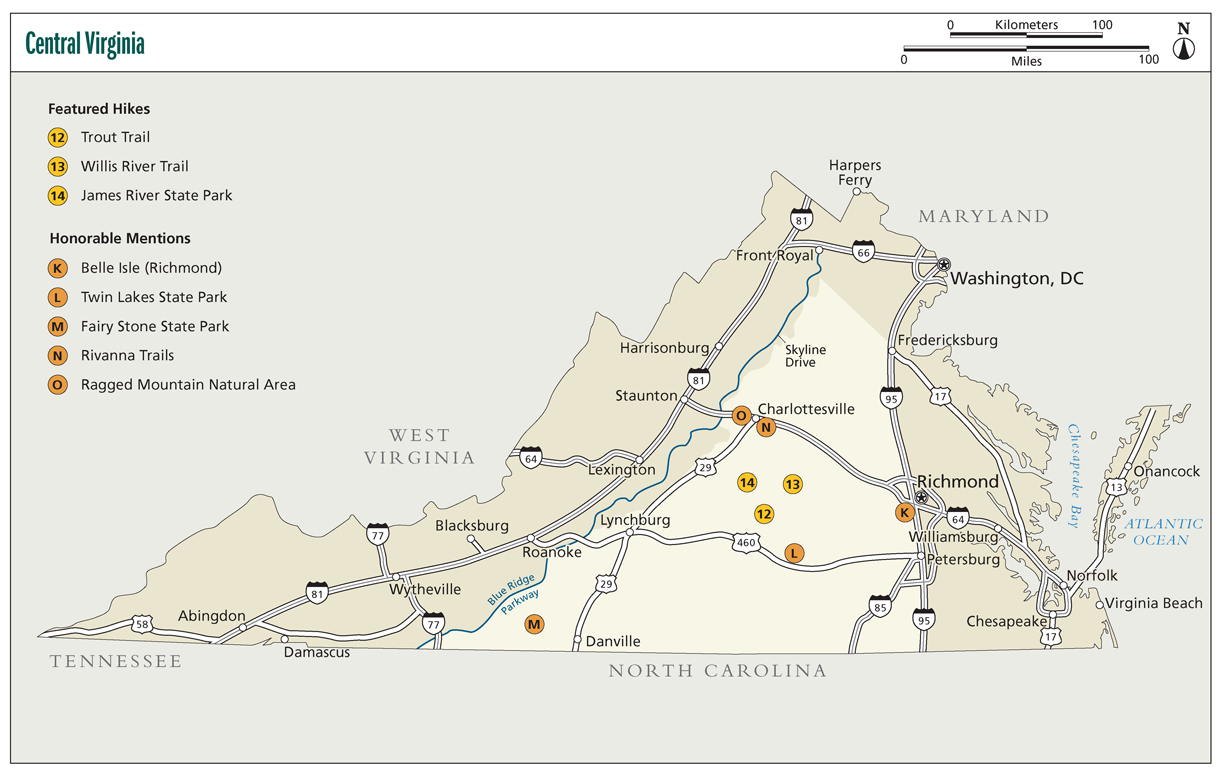

12. Trout Trail

13. Willis River Trail

14. James River State Park

HONORABLE MENTIONS

K. Belle Isle (Richmond)

L. Twin Lakes State Park

M. Fairy Stone State Park

N. Rivanna Trails

O. Ragged Mountain Natural Area