Making Up Little Women

WHEN ASKED TO WRITE a novel for girls, Alcott had decided to base it on herself and her sisters, thinking, “Our queer plays and experiences may prove interesting.” Upon completing the novel, she reflected, “we really lived most of it.”1 Having first discovered her “true style” while revising her letters for her book Hospital Sketches, she again wrote from her own life, creating the most lifelike book for children that had yet appeared. As a result, she became a celebrity not only as the author of Little Women but also as its protagonist, Jo March.

Early reviewers assumed that the novel drew on the author’s life, and readers often wrote to Alcott as if she were Jo herself. The publisher also promoted the association of the Marches with the Alcotts, using one such fan letter as an advertisement. It begins, “Dear Jo, or Miss Alcott,” and continues, “We were all so disappointed about your not marrying Laurie.” Alcott even liked to call herself Jo and later added notations in her journal about which episodes had informed scenes in the book. For instance, next to a passage about living in a Boston apartment and writing to support herself, she wrote, “Jo in the garret.”2 In writing to fans, she referred to her family as “the Marches” and to each of her three sisters as the names of their fictional counterparts: Anna became Meg, Lizzie became Beth, and May became Amy. This connection between life and text would be carried through the many biographies and retellings of the Alcott story that began to appear immediately after her death.

It is safe to say that Alcott’s family and her experiences inspired many of the characters and episodes in Little Women, especially in part one. However, the full story of their lives could not be represented in a book for young people, containing as it did extreme poverty, religious radicalism, marital strife, suicidal thoughts, and possible mental illness. Louisa had a much rougher time of it than Jo ever did. Still, the great charm of the book remains its realism, which is based on the pranks, dreams, and growing pains of four very real girls. As Alcott says in Little Women of even Beth, the most seemingly idealized of the novel’s characters, she was “not an angel, but a very human little girl.”3

PROBABLY THE MOST surprising fact about the Alcotts, contrary to the cozy ideal of home and family life immortalized in Little Women, is that the family moved incessantly—over thirty times before Louisa was in her midtwenties. Not only that, but the Alcotts were many times temporarily separated and occasionally in danger of being broken up altogether, due to her father’s instability. In fact, the most conspicuously absent character in the book—Mr. March—is more or less based on the most formative person, for good and ill, in Louisa’s life: her father.

Many have speculated about why Louisa chose to practically cut her father out of Little Women, sending him off to war in the first part and leaving him in the background in the second. But it is no wonder, considering how frequently Bronson was absent from the family in real life. When Louisa was just a baby, Bronson left a pregnant Abigail alone with two small children in Germantown, Pennsylvania, for eighteen months so that he could have his own room near the library in Philadelphia where he studied literature and philosophy, making up for the substandard education he had received as the son of a poor farmer. He visited his family on weekends, but Abigail was depressed and endured her first of many miscarriages alone.4

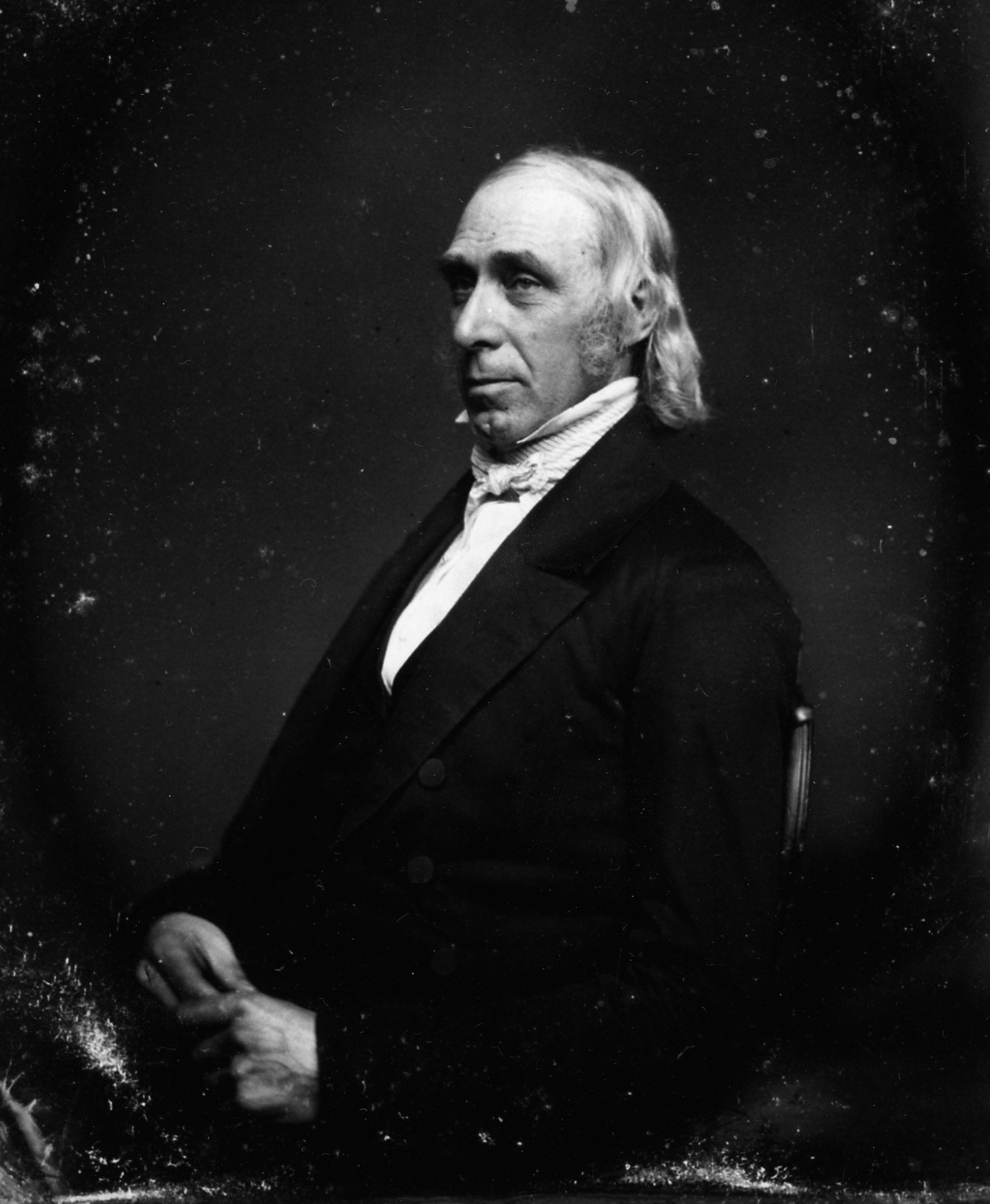

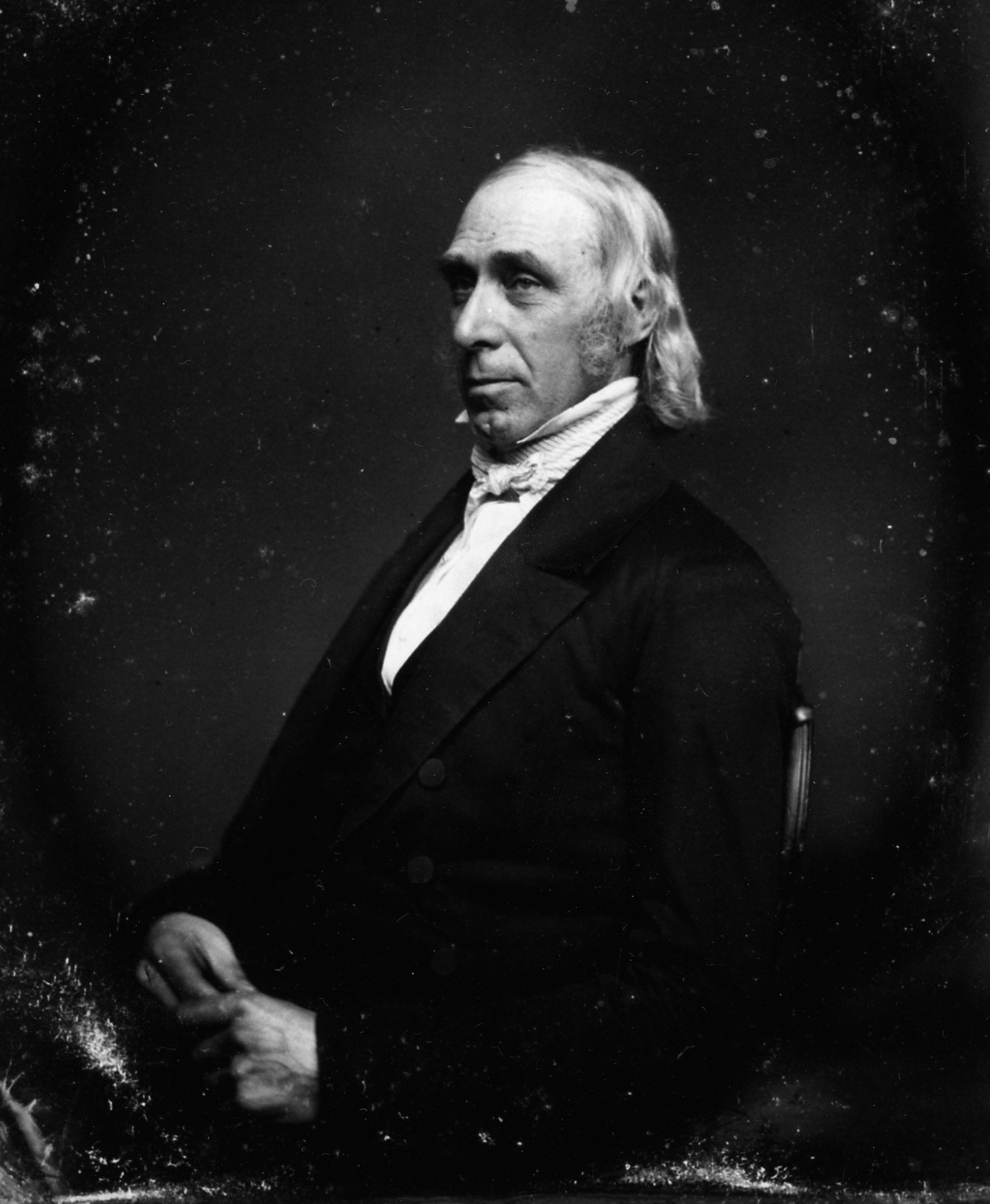

Bronson Alcott was largely excluded from Little Women. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House)

In 1842, when Louisa was nine years old, Bronson’s close friend Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote of him, “He is quite ready at any moment to abandon his present residence & employment, his country, nay, his wife & children, on very short notice, to put any new dream into practice which has bubbled up in the effervescence of discourse.”5 By then Bronson had already left on numerous travels, as he would many times more. Like his favorite character, Christian from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, he believed that spiritual awakening was more likely to be found away from home and family. And, like Christian, he hit the road in search of it.

Bronson’s primary aim was to live a spotless spiritual life. He strove for serenity, goodness, and selflessness. He was not content to wait for Heaven to discover the pure source of divinity. He wanted the heavenly estate revealed here on Earth, and he was going to help make that happen through teaching, farming, or simply leading what he considered an exemplary life. A letter he wrote to his children in 1841 exhorted them to take Jesus Christ as their model, as he did: “He did not give himself to the indulgence of appetites or passions, but governed himself in all things. He ruled his own spirit: he obeyed his Conscience.”6 Bronson set the bar high for his daughters, but it was not, in his eyes, unreachable. Like his transcendentalist friends, he did not think of Jesus as exceptional. He believed that divinity was located in each of us and that it was our duty to resist any conditions that hindered our ability to discover and fully express it.

Adhering to no church’s doctrine, Bronson was fanatical about following his own conscience, which prohibited the earning of filthy lucre and the amassing of goods for his own comfort or pleasure. He found some like-minded friends but very few who were as willing as he was to abandon all pursuit of material gain. His friend Henry David Thoreau perhaps best approximates his anti-materialist fervor, yet while Thoreau could leave civilization behind and create his own Eden on Walden Pond, Bronson had to figure out how to live an unencumbered existence with a wife and four daughters in tow. His friend and neighbor Ralph Waldo Emerson admired his ideas but had no intention of giving up his own family and comforts. Exasperated with Bronson’s impractical idealism at times, Emerson nonetheless was a frequent benefactor of the Alcotts, surreptitiously slipping money under a book or behind a cushion, lest Abigail’s pride be touched. He also helped them purchase their first stable home, Hillside, near him in Concord.

Bronson was happy to accept such charity, or reasonable payment for his lectures, teaching, or writing. The last two he failed at, however, at least in the sense that they earned him no money. The lectures brought in some income sporadically over the years, but he could never hang on to what he earned. Before he married, Bronson famously worked on and off as a peddler selling his wares all over the South, only to give up his business after five years, $600 in debt. Much later in life, after a long lecture tour out West essentially peddling his ideas, he came home to his wife and daughters with little more than the clothes on his back. One family story provides a glimpse of where the money went when it did come: Abigail once gave Bronson $10 to buy her a shawl for the winter while he was in town. He came back instead with a much-coveted book he had seen in a shop window, having entirely forgotten the shawl.7

Abigail had been at first drawn to Bronson’s ideals, and she would continue to admire them throughout their forty-seven-year marriage. She was herself an ardent abolitionist and an advocate of all-around reform. She came from an elite Boston family, but she broke from their politics, like her brother to whom she was very close. Samuel Joseph May was a leading reformer, an early supporter of women’s rights, and founder, with William Lloyd Garrison, of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. He was a minister who was called Mr. May, making him, quite possibly, another influence on Louisa’s creation of Mr. March. The family name of the Marches clearly comes from the Mays.8

Yet Abigail also suffered under the weight of her husband’s convictions, particularly as the family grew. Biographers and scholars of the transcendentalist circle have painted her as prone to harsh words and rancorous outbursts. One can hardly blame her. In one of Little Women’s most revealing passages, Marmee explains to Jo her difficulties in controlling her own anger. She “found it easy to be good” when she first married. “But by and by, when I had four little daughters round me, and we were poor, then the old trouble began again; for I am not patient by nature, and it tried me very much to see my children wanting anything.”9 In those few words are packed the years of extreme poverty the Alcotts endured and the anger Abigail felt about it.

Bronson has been called many unflattering things over the years, as the causes of the family’s poverty became known. Some critics have chosen to overlook his negligence toward his family in a material sense, stressing the spiritual and intellectual gifts he bestowed on them. But for most of us, it is hard to overlook his refusal to do anything but the few types of work he considered honorable, at which he largely failed, even to support his family. He had no qualms about borrowing from others (usually Abigail’s family members) or accruing insurmountable debts. The Alcotts were at times in so deep over their heads that they simply had to move away to escape their creditors. A common saying of Bronson’s was “the Lord will provide.” If He did not, then Bronson seemed, in Abigail’s opinion, quite willing to starve. She once wrote to her brother, “No one will employ him in his way [as a teacher]; he cannot work in theirs, if he thereby involve his conscience. He is so resolved in this matter that I believe he will starve and freeze before he will sacrifice principle to comfort. In this, I and my children are necessarily implicated.”10 What could possibly make a man so obstinate that he was willing to allow his own family to starve? This is not a simple question to answer.

Despite later assessments by those who have found Bronson’s character wanting, accounts from those who knew the family indicate that he was much beloved within and outside of his family. He famously possessed a guileless, childlike manner and “air of serene repose” that endeared him to many. His family shared his view that their era’s “lack of reverence for goodness and wisdom” (Abigail’s phrase) was primarily to blame for Bronson’s inability to earn a living. Although Abigail grew frustrated with him at times (she once burst out, “I do wish people who carry their heads in the clouds would occasionally take their bodies with them”), she and her daughters stood by Bronson when the world turned against him.11 He became an object of ridicule in 1837 after the publication of Conversations with Children on the Gospels, which was roundly criticized in the press as sanctimonious, blasphemous, even dangerous. Parents promptly removed their children from his Temple School in Boston, and his reputation was so tarnished that he could not simply move and open another.

In Little Women, there is a sense of an earlier golden age that has ended because Mr. March gave away his fortune to others needier than himself. In real life, it was less a fall from prosperity than a fall from grace. Bronson’s supreme belief in himself and his views made others sneer at his self-righteousness. The Alcotts left Boston in 1839, broken in spirit and $5,000 in debt. The always supportive Emerson drew them to Concord, where they would live on and off for nearly the rest of their lives.

Bronson was known by all to be eccentric, another reason Louisa probably left him in the background of her novel, not wanting to expose him to further ridicule. But even more than simply eccentric, I think it fair to consider Bronson a kind of religious fanatic, forbidding his family to engage in many practices he viewed as sinful. While he was quite liberal in his encouragement of his daughters’ talents and energies, he restricted them in other ways. For much of Louisa’s childhood, she was improperly clothed and subsisted on little more than bread and water, making her “skinny, undernourished, and usually hungry,” according to one of her biographers. The family’s poverty was only partially to blame. Bronson would abide no meat at the table, or any other animal products: milk, butter, cheese, or eggs. Fruits and vegetables, preferably those that grew aboveground, were allowed when nature provided them. Bronson’s reverence for animals also meant that no wool could be stolen from the sheep, and his abhorrence of slavery led him to forbid cotton. Linen was the only material fit for their backs, even during the cold Massachusetts winters. Similarly, “foreign luxuries,” such as sugar, molasses, rice, tea, and coffee were also banished, recalled one friend of the family. These products not only polluted the body but corrupted the soul.12

Bronson’s strict views reached their height in 1843 at Fruitlands, the utopian community he founded in Harvard, Massachusetts, with his English friend Charles Lane. Abigail watched as Bronson became ever stricter in his beliefs and even seriously considered breaking up the family in favor of communal living after the fashion of the Shakers, some of whom lived nearby. After seven months at Fruitlands, it became clear that the community was incapable of surviving through the winter. Abigail was determined to take her children away to prevent their being starved or frozen to death. Little Louisa, only eleven years old, wrote in her journal in December that the family had had a tearful talk. Afterward, “Anna and I cried in bed, and I prayed God to keep us all together.”13

Finally, once all of the other Fruitlanders had left, Bronson lay down in his bed and turned his head toward the wall, refusing to eat and waiting simply to die. He believed, no doubt, that God had not deemed his enterprise worth providing for. This went on for days while Abigail and the girls tried to coax him back to life. Louisa describes the event at length in her later fictional account of the Fruitlands experiment, “Transcendental Wild Oats,” but she does not describe how she and the rest of her family must have felt watching the captain of their ship abandon his post and all will to live. Fortunately, Abigail had been scouting out an alternative abode for herself and the girls. She did not want to leave her husband behind to die, though, so she mustered all of her strength and finally convinced him to eat and drink again. She got him and her four girls into a sled and brought them to a home in nearby Still River, where they regrouped and recommitted themselves to each other. The lesson that Fruitlands taught them was that the family unit was sacred and must stay together, no matter what, a lesson that permeates Little Women.

After the Fruitlands debacle (and possibly before), Bronson had periods of mental instability. His biographer John Matteson avoids using the word insanity, which earlier biographers have used, and instead settles on manic depression, which included, at various times, disturbing visions, nightmares, and delusions of being Christlike, a martyr, or “not merely God but, indeed, ‘greater than God.’ ” These mental states were particularly acute during the family’s time at Still River. But as he grew older, Bronson became a gentler, less fanatical father who did not worry his family as much. (However, his brother’s suicide in 1852, which is barely mentioned in surviving documents, must have increased their concern of hereditary mental illness.) Bronson also gradually relaxed his strict beliefs, allowing the girls to wear warmer clothing and later to eat dairy and meat. Yet he never could contribute much materially to the family’s welfare, believing simply that his gifts were not valued by his contemporaries and thus were not remunerable. He appears never to have considered becoming other than he was. His family would always think of him as the philosopher who “live[d] in the clouds” while they of the “earthly mould” took care of life’s practical matters.14 Over time, he became a kind of lovable misfit, out of place in the nineteenth century and therefore a man to be pityingly adored more than revered. Louisa called him Plato and joked in her letters about his utter lack of pragmatism, even telling the story of the forgotten shawl with a smile rather than bitterness.

Nonetheless, Louisa was deeply marked by these early experiences of poverty, family instability, and worry for her father’s sanity. She watched her mother become the family’s main support by taking in boarders, sewing, and other manual labor, and, as a result, losing her physical health and vigor. Louisa once said, in her father’s presence, “It requires three women to take care of a philosopher, and when the philosopher is old the three women are pretty well used up.” She understood her mother’s failed hopes of an intellectual companionship with her father as well as her desperate need to idealize him while repressing her anger about his inability to provide for his family. Most of all, Abigail resented Bronson’s inability to see her sacrifices, a failing she understood as not merely peculiar to him. Abigail possessed a vivid consciousness of the inequality of the sexes and the desire to redress women’s wrongs, which she passed on to Louisa. During the Fruitlands episode, Abigail wrote in her journal, “A woman may perform the most disinterested duties. She may ‘die daily’ in the cause of truth and righteousness. She lives neglected, dies forgotten. But a man who never performed in his whole life one self-denying act, but who has accidental gifts of genius, is celebrated by his contemporaries, while his name and works live on, from age to age. He is crowned with laurel, while scarce a ‘stone may tell where she lies.’ ” It is no wonder that as Louisa grew into womanhood, she had no inclination to marry. She learned early that “to be a woman in the world, particularly a married woman, was to be subservient and neglected.”15 Louisa also sought to redress the wrong of Abigail’s life, making it her mission to honor her mother’s legacy. If Mr. March is largely absent in Little Women, Marmee permeates every page.

Louisa also called her mother Marmee, which they likely pronounced “Mawmmy” or “Mommy,” in the New England accent. Marmee is in many ways an idealized version of Abigail May Alcott, a reflection of her spirit without her sharp edges. Although Marmee admits to being “angry nearly every day of [her] life,” she does not possess the bitterness that the real Abigail found it difficult to conceal.16 Abigail’s journals became an outlet for her true feelings, so much so that she requested they be burned upon her death. Louisa carried out her wishes to some extent, and Bronson heavily edited and excised them, destroying many, finding it painful to read how unhappy she had been, the extent of which he apparently had not realized.

Marmee is an idealized portrait of Louisa’s mother, Abigail May Alcott. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House).

If Abigail was angrier than the Marmee of Little Women, she did possess the same fierce belief in her girls, advising them, in biographer Eve LaPlante’s summation, “A woman can accomplish as much as a man, . . . Educate yourself up to your senses. Be something in yourself. Let the world know you are alive. Push boldly off. Wait for no man.” Abba, as she was called, did not pressure her girls to marry and regretted how much “girls are taught to seem, to appear—not to be and do.”17 She made sure her girls understood that their true worth lay in their minds and characters and not in their looks. She also wanted them to be able to support themselves. When Jo tells Professor Bhaer that she intends to work when they marry, she does not simply speak on principle but out of pragmatism. Depending on a husband for one’s bread, Louisa learned from her mother, was foolish.

Unable to receive sufficient emotional and material support from her husband, Abigail instead looked to her daughters. None repaid her as well as Louisa, who was closest to her in looks and temperament. They shared, in LaPlante’s words, a “marriage-like bond,” an intimacy that exceeded all others. It is little wonder that as Louisa grew up she determined to provide for her mother. When she was only ten, her mother wrote to her, “In my imagination I have thought you might be such an industrious good daughter and that I might be a sick but loving mother, looking to my daughter’s labors for my daily bread.” Louisa would soon take up that responsibility in earnest, determining that one day she would provide for her a comfortable home without any debts hanging over her head. This aspect of Louisa’s life, echoed in her father’s characterization of her as “Duty’s faithful child,” would come to define Louisa in the popular imagination.18 For many years after her death, as a number of (especially juvenile) biographies appeared, the perception of the self-sacrificial Louisa who rose through hardship and poverty to support her family as a famous author prevailed. Yet the real Louisa was much more complex, more so than could ever be contained in her most famous portrait of herself as Jo March.

JUST AS JO, short for Josephine, possesses a masculine nickname, so did Louisa, who was known as Lou, Lu, or Louie in the family. Her relatives considered her “an odd, grahamish, transcendental, half educated tom boy” who wouldn’t amount to much, which sounds a lot like Jo in some respects. In her portrayal of Jo, Louisa was careful to avoid the “grahamish” (referring to the vegetarian beliefs of Sylvester Graham, inventor of the Graham cracker) and “transcendental” philosophical parts, both of which she inherited from her father. Like Jo, however, she was a bit of a misfit, much louder and more rambunctious than her sisters. She felt like the son or brother of the family. Many of the friends and relatives who wrote reminiscences of the Alcotts recall how much she acted like and wanted to be a boy. As one friend of Lizzie’s later recalled, she was always scandalizing people with “her tomboyish, natural, and independent ways.”19

Louisa also found it difficult to control her temper, as Jo does. A close childhood friend explained that she was subject to moods that could make her the most delightful companion when she was jolly, “but, if the opposite, let her best friend beware.” She was known once to have hung a chair outside her window as a punishment for the chair being in her way when she was cleaning.20 Louisa also had a difficult time containing her desires; she would never meet her father’s ideal of Christ-like self-denial. She longed for food she was not allowed to eat, making her feel lustful and sinful, as if her character were to blame rather than her grumbling stomach. She wanted nice clothes and books to read, the same things all of the March girls yearn for. In short, she wanted no longer to be poor, a very natural desire that she was taught to see as pernicious. In life, Louisa learned to channel her selfish desires into selfless ones—a main theme in Little Women for all of the girls, but especially for Meg and the most covetous of the March girls, Amy. Patience and contentment were the most difficult lessons for Louisa to learn as a child. She was convinced that she was not “good,” as her older sister, Anna, was, a perception her father reinforced in myriad ways, not least by equating his own and Anna’s fairer coloring with angelic serenity and Abigail and Louisa’s dark hair and complexions with passionate, disturbed minds.

Louisa found an outlet for her strong emotions, as she has Jo do, in performing theatricals and writing sensational stories. The pent-up anger, jealousy, and other errant emotions she experienced were channeled into stories she and Anna could act out for family and friends in a suitable environment: their home. Her mother also encouraged her journal writing as a way to examine herself and learn to control her emotions. It is not surprising that Louisa destroyed most of her journals from the 1840s and ’50s, the most difficult years for the family and for Louisa herself as she grew from a willful child into an anxious young woman.

There were joyful times too, of course, particularly from 1845 to 1848 when Louisa, ages twelve to fifteen, lived in Concord at the home they called Hillside. (Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family would later live there and call it Wayside.) Louisa and Anna had, for the first time, rooms of their own. Louisa reveled in the freedom to read and write alone in her room or run in the woods behind the house. She loved to run so much that she imagined herself to have been a deer or horse in a former life. “No boy could be my friend till I had beaten him in a race,” she explained, “and no girl if she refused to climb trees, leap fences and be a tomboy.” She was the fastest runner around, her friend Clara Gowing recalled, and impressed everyone by running and climbing just like a boy. In Little Women, Jo enjoys running with Laurie but is scolded by Meg for it.21

While living at Hillside, the Alcott girls also made a “post office” out of a hollow tree stump and exchanged letters with Clara, as the March sisters do with Laurie. They also played Pilgrim’s Progress and spent much of the day outdoors playing with friends, as the March girls do in the “Camp Laurence” chapter of Little Women. Those years were the happiest of her life, Louisa later reflected, so it is not surprising that she looked back to them for many of the episodes in the first part of Little Women. In fact, at the beginning of the novel, Jo is the age (fifteen) that Louisa was when they had to move away from Concord and Hillside.22 By placing her story there, she imagined what it would have been like had they been able to stay.

While bucolic Concord and the frolics they enjoyed there made it into Little Women, Alcott whitewashed her family’s poverty and the troubles they endured because of it. She later reflected that those were the days when her cares began and her “happy childhood ended.” In the novel’s opening, we hear the girls complaining about their lack of money: “ ‘Christmas won’t be Christmas without any presents,’ grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.” At least one Alcott Christmas, during the Civil War, was celebrated without any presents. We also see the March sisters give away their Christmas breakfast to the impoverished Hummels, a scene taken from life. Alcott described the same scene in a “true story” she wrote just before starting Little Women, and Abigail was known to give away what little they had to others who were suffering more.23

What Alcott didn’t want to show, however, was how much her family depended on charity themselves. In Little Women, the Marches’ wealthy neighbor, Mr. Laurence, bestows upon the girls a Christmas feast of cake, ice cream, and candy after he sees them giving away their modest breakfast, and he later gives Beth a piano. Accepting treats and the occasional luxury you can’t afford is much less humiliating than being the recipient of necessities you are too poor to provide for yourself. In reality, friends and relatives gave the Alcotts clothing, food, money, and rent-free accommodations and sometimes took in one of the girls. In 1847, for instance, fourteen-year-old Louisa spent part of the summer with friends near Boston, sixteen-year-old Anna spent the fall teaching in Walpole, New Hampshire, while living there with relatives, and twelve-year-old Lizzie was sent to stay with family in Boston during the winter.24 The cozy nuclear family of the Marches (nearly) all under one roof was rarely a reality for the Alcotts. More typical were the separations we see in part two of Little Women, as the girls grow up. Jo goes to New York because she wants to spread her wings, but in real life, necessity often drove the girls away from home. Anna and Louisa spent much of their adolescence and twenties working in other towns, supporting themselves and sending money home when they could. Once, in the summer of 1848, even Abigail left home. Desperate to support her family, she took a job as the matron at a water cure spa in Maine for three months.

Even when the Alcotts were all together, they often weren’t the only ones there. Sometimes one or more of Bronson’s friends lived with them, as did boarders, many of them children who were being taught by Bronson, Anna, or Louisa and cared for by Abigail. For two years while they were at Hillside, Abigail cared for a mentally disabled child who boarded with them. Often they also took in strangers who needed help, with no concern for monetary return, including runaway slaves, one of whom Louisa recalled teaching to write. Louisa later wrote that they provided “shelter for lost girls, abused wives, friendless children, and weak or wicked men.”25

When it became clear they could no longer support themselves in Concord, the Alcotts made the difficult decision to move to Boston. Hillside, which they had bought with Abigail’s inheritance from her father, required too much upkeep, whereas in Boston they could rent rooms while Louisa and Anna looked for employment as teachers and Abigail worked as a “missionary to the poor.” After the difficult family meeting that led to this decision, Louisa ran over the hill behind the house “for ‘a good think’ ” and determined, “I will do something by-and-by. Don’t care what, teach, sew, act, write, anything to help the family; and I’ll be rich and famous and happy before I die, see if I won’t.”26 She would go on to do all of that and more in an effort to help support her family.

While the Alcotts lived in Boston, Abigail was one of the country’s first professional social workers as well as director of an employment agency, jobs that barely earned enough for a small apartment without indoor plumbing in the city slums. They had to move so frequently in search of tolerable accommodations, and in and out of temporary homes loaned by absent relatives, that the girls didn’t even bother to unpack their trunks.27 The mixed feelings of resentment and gratitude that Louisa felt toward her mother’s wealthy kin, on whom they were often dependent, are reflected in her portraits in Little Women of Aunt March and Mr. Laurence: the former provides her charity grudgingly, the latter is happy to help when he can without wounding the Marches’ pride.

The Alcotts were not together in Boston for long before Bronson left to spend the summer with friends in Concord. Anna left to work as a nursery girl and then as a governess before moving to Syracuse, New York, to teach in a mental institution. She would live in Syracuse with Abigail’s brother and his family for many years with only occasional visits to her own family. Louisa missed Anna terribly. She kept house and tried various teaching schemes while Lizzie and May went to school, something the older girls had not been able to do, except for one year while they lived in Concord.28

While trying to teach and to publish her stories and poems, Louisa once took a job as a live-in servant for a family she thought respectable. The experiment proved disastrous. She was made to do the most demeaning, backbreaking work in addition to enduring her male employer’s advances. When she finally quit, she was paid a mere $4 for seven weeks of work. These degrading experiences would make their way into Louisa’s adult novel Work, written earlier but published after the success of Little Women. In many ways, Work reflects Louisa’s difficulties as a wage earner more accurately than Little Women, in which the worst Jo endures is Aunt March’s crankiness. Yet Jo perfectly channels Louisa when she realizes “that money conferred power,” and she resolves to have it “not for herself alone, but for those whom she loved more than self.”29

At about this time, Louisa was even willing to sell her thick, dark hair, which hung down almost to the ground. When an onerous debt weighed upon her family, as she later told a friend, “I went to a barber, let down my hair, and asked him how much money he would give me for it. When he told me the sum, it seemed so large to me that I then and there determined I would part with my most precious possession if during the next week the clouds did not lift.” Fortunately, a friend came to the family’s aid and Louisa’s hair was spared, but she would lose it during the war when she fell ill with typhoid fever after nursing in Washington, D.C. Louisa was terribly sad “about losing my one beauty.”30 All of this would make it into Little Women, where Jo sells her hair for $25 when they learn that Mr. March is ill and Marmee must make the journey to Washington to nurse him. And, of course, it was Louisa, not her father, who went to war and had to be brought home after falling seriously ill.

Particularly reflective of Louisa’s experiences during these years are Jo’s attempts to find her path to money and power through writing. Louisa said nothing to her family about her first publication, “The Rival Painters,” in 1852, but simply read it aloud to them. Only when they praised the author did she reveal that it was herself, just as Jo does in Little Women. Under Louisa’s direction, the Alcott girls also carried on a family newspaper irregularly from 1849 to 1851, whenever they could all be together to work on an issue. It was called at first The Olive Leaf, then The Portfolio, and then The Pickwick and was full of the stories and advertisements of which there is a sample in the March girls’ Pickwick Portfolio. Not long after, when the family lived in Pinckney Street, in Boston, twenty-year-old Louisa wore a special cap and cloak her mother had made for her and went up into the garret to write. “I am in the garret with my papers round me,” Louisa wrote (sounding a lot like Jo), “and a pile of apples to eat while I write my journal, plan stories, and enjoy the patter of rain on the roof, in peace and quiet.”31 Alcott also gave Jo her experiences of writing her first novel, Moods—going deeply into her vortex, having to cut the manuscript down to fit the publisher’s specifications, and fretting over the conflicting reviews she received. And, as with Jo, sensation stories became her primary source of income.

Louisa May Alcott in her twenties, as she struggled to begin her literary career and help support her family. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House)

While Louisa’s literary career developed, the family was again on the move. In 1855 the Alcotts were offered a home by Abba’s brother-in-law in Walpole, New Hampshire. Louisa lived with her family there for a while before returning to Boston to work. It was after Louisa left that the two youngest daughters, Lizzie and May, contracted scarlet fever from a poor immigrant family, the Halls, whom their mother was helping to care for. (The Halls would become the Hummels in Little Women.) May got well quickly, but Lizzie, like Beth, almost died and never fully recovered.

Lizzie is a shadowy figure in her family’s private writings, much as Beth is in the novel. She refused to read her journals aloud to the family as the other sisters did, an indication of shyness but also of unwillingness to reveal her deepest self, even to those closest to her. She also declined to perform in the girls’ homegrown theatricals, limiting herself to making props and stage scenery. She loved to play the piano but had none of the artistic ambitions of her sisters. Bronson called her his “Little Tranquility.” In fact, she among the four sisters seemed to have most inherited his serene disposition. She also may have inherited the depression that hid behind it. Five years before, Abigail had written to Bronson, then away in Cincinnati, that Lizzie seemed to suffer from “some collapse of the brain,” which could be her way of describing depression. “At times she seems almost immoveable—almost senseless. . . . There is a great struggle going on in her mind about something,” Abigail wrote. Similarly, in Little Women, Marmee is worried about Beth’s “spirits” as much as she is about her health. In her journals, Louisa once mentioned Lizzie having “a little romance” (perhaps echoed in Jo’s suspicion that Beth is in love with Laurie), but otherwise her references to Lizzie are unremarkable: glimpses of her going to school, teaching a little, and being the “the home bird” and the “little Cinderella” of the house.32

After she became ill, however, Lizzie became an object of much concern. Louisa wrote in June 1857 that she feared Lizzie would “slip away; for she never seemed to care much for this world beyond home.” By October, Lizzie was little more than “a shadow.” During her time in Walpole, the ill Lizzie also received a piano from a wealthy benefactor, as Beth does from Mr. Laurence in Little Women, and Abigail took her to the seaside in hopes of restoring her health. When she didn’t improve, they finally took her to Boston to consult a doctor. The family greatly distrusted the medical establishment, and with good reason. Physicians had a poor record of accurately diagnosing and treating disease. The Alcotts put their faith in an alternative medicine then quite popular: homeopathy, based on the idea that “like cures like” or that very small doses of substances producing the same symptoms already suffered can combat a disease. Lizzie may have been given belladonna in the early stages of her illness, as Beth is in Little Women, since it was considered an effective homeopathic treatment for scarlet fever.33

The only known portrait of Lizzie Alcott, immortalized as Beth in Little Women. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House)

It is not clear what Lizzie’s long-term malady was. Alcott biographers have conjectured that it was rheumatic fever, which can follow scarlet fever and lead to heart failure, or psychological causes, including that she may have been starving herself. What is clear is that she was slowly wasting away, hence one doctor’s diagnosis of consumption, or tuberculosis. Another doctor diagnosed “atrophy or consumption of the nervous system with the great development of hysteria,” nineteenth-century lingo for what we would call chronic depression and/or anxiety. We know that she suffered from “weight loss, weakness, stomach pains, nausea, vomiting, sweating, hair loss, depression, irritability, drowsiness, and restlessness.” Depression seems to have made her resign herself to, or even wish for, death. She was convinced, she told her mother, that she could “best be spared of the four.”34

Louisa nursed her sister in her final months and weeks. She watched as Lizzie sewed little presents to drop out of the window to passing schoolchildren until, like Beth, she could no longer hold her needle. On March 14, 1858, Lizzie drew her last breath. Afterward, Abigail and Louisa dressed Lizzie’s body, “a form chiseled in Bone, held by a mere integument of skin, no flesh perceptible,” Abigail wrote in a letter to her brother. Although only twenty-three, she looked as if she were forty, Louisa thought. Moments after her death, they also witnessed a mist rise from her, which the doctor told them was but the visible manifestation of her life leaving her body. Louisa chose not to include this remarkable event in Little Women, nor did she describe the extent of Lizzie’s wasting away, choosing to omit as well that she had lost all of her hair. Beth dies peacefully, while poor Lizzie endured intolerable pain in the end. Having long refused medicine, she nonetheless cried out for something to relieve her pain. A poem Bronson wrote after her death begins, “ ‘Ether,’ she begged, ‘O Father give[’],” and continues, “We had it not,” indicating how helpless her family felt in the face of her painful death.35

After Lizzie’s death, Louisa suffered a serious emotional crisis that was compounded by her sister Anna’s engagement to be married. In the novel, Meg marries many years before Beth dies. In real life, however, Anna became engaged only a few months after Lizzie’s death, sending Louisa into a tailspin. She fled Concord, where the Alcotts had recently purchased Orchard House, and tried unsuccessfully to find work in Boston. Without the mooring of her family, which seemed to have broken apart, Louisa found herself one day contemplating jumping into the swirling waters of the Charles River. She told her family, “My courage most gave out, for every one was so busy, & cared so little whether I got work or jumped into the river that I thought seriously of doing the latter.”36 She would later describe the episode in her adult novel Work, but the depth of her despair was not fit for a novel for young people.

In May 1860, after a two-year engagement, Anna (“Nan”) married John Pratt, who had lived as a child at Brook Farm, a far more successful utopian community than Fruitlands was. (Thus he becomes John Brooke in Little Women.) However, while Anna’s fictional counterpart, Meg, meets John Brooke at the age of seventeen and marries him at twenty, Anna was twenty-nine on her wedding day, an event that bore many similarities to the one described in the novel. Louisa had been very close to Nan and must have thought they were both destined to stay unmarried and grow old together.

Anna had dreamed of being an actress, just as Louisa had dreamed of becoming a famous author and May a famous artist. No hint of Anna’s ambition made it into Little Women, perhaps because of the great stigma attached to acting for women. Louisa explored the theme in another precursor to Little Women, the story “The Sisters’ Trial,” in which four orphaned sisters have to find work to support themselves. One, Nora, lives by her pen; Ella becomes a governess; Amy will be a paid companion on a tour of Europe, where she hopes to develop her skill as an artist; and Agnes decides to try her luck on the stage. After one year, all of the girls but Agnes have prospered. Nora and Ella are to marry, Amy is to be an artist, and Agnes has worked hard only to discover that the man she loves has spurned her because she makes her living on the stage. She therefore leaves acting behind and “endeavor[s] to become what he would have me: not an actress, but a simple woman, trying to play well her part in life’s great drama.”37 Interestingly, Anna had met John Pratt while performing together in the Concord theatricals. But participating in community theater for fun or charity was a far cry from professional acting, which required an exposure both physical and emotional that was deemed to compromise a woman’s morals and make her unfit for private domestic life. In her portrait of Anna, Louisa therefore chose to limit Meg’s interest in the theater and make her “castle in the air” about having a “lovely house, full of all sorts of luxurious things.”38 Louisa also emphasized Anna’s traditionally feminine qualities of docility and domesticity and made Meg a conventional beauty. Louisa felt she had to make at least one of the March sisters pretty.

Anna “Nan” Alcott, who became Meg in Little Women, dreamed of becoming an actress. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House)

Louisa gradually accepted her older sister’s choice to marry, but as Anna left the family, the primary responsibility to maintain those left behind fell to Louisa. After a short period of freedom in Boston, Louisa had in 1859 returned to Concord and Orchard House, which she called “Apple Slump” because the floors sloped. It would be the Alcott family home for the next eighteen years. It was where Anna would marry, the family would live through the war, Louisa would write Little Women, and the youngest daughter, May, would become an artist. While Louisa struggled to establish her literary career, the money she earned from her sensation stories went to buy household necessities, comforts for her mother, and art lessons and supplies for May.

May was named Abigail May Alcott, after her mother. Her family called her Abby, although starting in her adolescence she asked them to call her May. Eight years younger than Louisa, she was raised by her older sisters as well as her parents. In personality, May was much like Amy in Little Women: a social butterfly with many “fashionable friends,” a girl who yearned for beautiful things and was the pet of the family. She could be, according to one family friend, “childishly tyrannical.” She had a happier childhood than Louisa simply by virtue of having missed the Temple School scandal and having been only three years old during the Fruitlands debacle. May’s greatest dream was to be rich and go to Europe to study art and become a famous artist. As a teenager she was often exempted from housework and allowed to go to school. When in 1864 a family friend offered to pay May’s way in art school, Louisa felt much as Jo does when Amy is chosen to go to Europe instead of her. Louisa was resigned in her jealousy, however, convincing herself that it was better to make her own way than have others readily help her, as May did. Years later, she wrote of May, “She always had the cream of things.”39 These comments make it easy to suspect that Louisa’s negative portrayal of Amy was motivated by her jealousy of May.

Orchard House, the home in Concord, Massachusetts, where Louisa wrote

Little Women, with the Alcott family in the foreground. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House)

May was not entirely pleased with her sister’s portrait of her in Little Women, writing to their close friend Alfred Whitman, “Did you recognize . . . that horrid stupid Amy as something like me even to putting a cloths pin on her nose?” Yet, she more or less admitted to being like Amy: “so superficial & career[ing] about with such noodles as Frank Wheeler.” She further reflects, “I used to be so ambitious, & think wealth brought everything,” but she had learned how to find happiness in hard work and in her pursuit of a career in art.40 In fact, May would do the illustrations for the first part of Little Women, itself a kind of sanction of her sister’s novel, and the two sisters became quite close after Nan married, living together for periods in Boston while Louisa wrote and May painted.

Louisa’s portrait of Amy in Little Women did not sit well with her youngest sister, May. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House)

Louisa couldn’t help noticing how much more the amiable May was liked by family members and friends than her blunt self, and her portrait of Amy and Jo’s visits to neighbors in part two of the novel pokes perhaps more fun at herself than at May. She also had Amy go to Europe, whereas it was Louisa who was able to travel abroad and witness the scenes that would form the backdrop of Amy’s adventures in Little Women. (After its publication, May would get to go to Europe with Louisa, thanks to the novel’s royalties.) At the time of the novel’s creation, May had, like Louisa, chosen art over a family of her own. Ten years later, however, May had established herself as a successful artist in London and Paris and decided, at age thirty-seven, to marry. The following year, after the birth of her daughter, she died suddenly, cutting short the experiment in love and art that Louisa had watched closely. The little girl, Lulu, named after her aunt, was sent to America to be raised by her famous relative.

Louisa’s first trip to Europe in 1865 contributed more than the background to Amy’s tour. It was also there that Louisa met the Polish Ladislas Wisniewski, whom she later claimed was her model for Laurie. In Little Women, Theodore Laurence’s Europeanness, his poor health, his lack of parents, and his talent as a pianist all come from Ladislas. The impossibility of a romance between Louisa and the younger Pole, whom she called Laddie, also comes through in the way Jo rejects Laurie, seeing him more as a brother than as a lover.

Ladislas was not the only model for Laurie, however. Three other young men also laid claim to that title. The most prominent was Julian Hawthorne, son of the novelist, who lived next door to Orchard House (at Wayside, formerly Hillside) and had a prodigious crush on May. Yet Louisa specifically said he was not Laurie. Bronson and Anna (but not Louisa, apparently) both told Frederick L. Willis he was Laurie, probably because the March girls’ romps with Laurie outdoors reminded them of the times Frederick, Anna, and Louisa played at the Bare Hill Pond near Still River. Frederick was an orphan whom Abigail had taken under her wing and treated as a son, and the girls felt sorry for him, as the March sisters do for Laurie. Willis recalled their first meeting as awkward, since he was a city boy and they were from the country. But Louisa proposed they go outside and play, and “we were comrades from that time forth.” Years later, when he visited at Hillside in Concord, they would run and climb trees together. And when he finally went away to college, she wrote him letters full of “frolicsome and serious advice and admonition,” much as Jo helps keep Laurie out of trouble during his college years.41

Alfred Whitman, who came to live in Concord when the Alcotts moved back there in 1857, was another motherless boy the family befriended. Nine years younger than Louisa—fifteen to Louisa’s twenty-four—he was a student at Frank Sanborn’s school and found in the Alcotts a replacement family. For many years after he moved to Kansas, Louisa, Anna, and May all kept up a correspondence with him. In her letters, Louisa called him “my boy,” as she has Jo call Laurie. Alfred later described the beneficent influence Louisa had over boys like himself, providing a glimpse of Jo not only in Little Women but also in the sequels, in which she mothers many boys and young men at Plumfield: “She never scolded, and scarcely ever preached” but molded their lives through affection and “silent influence.” After Little Women came out, Louisa wrote to Alfred Whitman that he and her Polish friend were combined in her creation of Laurie. “You are the sober half & my Ladislas . . . is the gay whirligig half.” She remembered Alfred as the serious boy “who used to come and have confidences on the couch, a la Laurie, & be very fascinating without knowing it.”42

None of the real-life candidates for Laurie was wealthy. By making Laurie heir to a great fortune, Louisa indulged her fantasy of an Alcott gaining the riches that she and her sisters had always dreamed of one day possessing. Such inheritances were common in her sensational fiction, where she regularly allowed wish fulfillment to reign. In life, none of the Alcott girls married rich men.

Jo’s marriage to Professor Bhaer, however, was not the product of fantasy but the result of pressure from Alcott’s publishers. They “insist on having people married off in a wholesale manner which much afflicts me,” Louisa wrote to a friend. “ ‘Jo’ should have remained a literary spinster but so many enthusiastic young ladies wrote to me clamorously demanding that she should marry Laurie, or somebody, that I didnt dare to refuse & out of perversity went & made a funny match for her. I expect vials of wrath to be poured out upon my head, but rather enjoy the prospect.” Louisa herself never wished to marry. Although in Little Women Jo begins to soften toward marriage and family after spending time with Meg and her babies, Louisa was not similarly moved by Anna’s domestic bliss. After visiting newlyweds Nan and John in their new home, she wrote, “Very sweet and pretty, but I’d rather be a free spinster and paddle my own canoe.”43

Louisa was happy to grow into adulthood without marrying, although she felt pressured to marry off her alter ego, Jo March. (Used by permission of Louisa May Alcott’s Orchard House)

Louisa seems to have had two opportunities to marry. There was a “funny lover” she met on a train in the month before Anna’s wedding. He professed to have “lost his heart” almost immediately. Louisa thought him handsome but odd. He was older, about forty, and from the South. She kept him at bay, although he wrote her letters and once attempted to visit her at Orchard House. She declined to see him, so he wandered the road like a forlorn ghost. Finally, he got the message. “My adorers are all queer,” she wrote in her journal. Another man, a Mr. Condit, offered her his hand in 1860. The fact that he was a “prosperous manufacturer of silk hats,” writes biographer Harriet Reisen, seems to have tempted Louisa. But her mother counseled her not to marry where there was not love, even for the comfort she could gain for herself and her family. It was about a month later that she decided she was content “paddl[ing] her own canoe.” Similarly, Marmee in Little Women tells Meg and Jo, “Better [to] be happy old maids than unhappy wives.”44

In choosing a mate for Jo, Alcott seems to have drawn on her attraction to older men like Thoreau and Emerson. Her great affection for them was most fully expressed in her earlier novel Moods, where the characters Adam Warwick and Geoffrey Moor can be recognized as idealized portraits of the two men. In Little Women, she seems to have particularly had Emerson in mind when she created the character of Professor Bhaer. Louisa called the transcendentalist philosopher “my beloved ‘Master’ ” and in her teens wrote chaste love letters to him, modeled after those Bettina von Armin wrote to Goethe and published in Goethe’s Correspondence with a Child, a book that Emerson loaned to her. Louisa also once sang Mignon’s song from Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister up to Emerson’s window. In Little Women, Jo overhears Bhaer singing the same song, Kennst Du Das Land? (“Do You Know the Land?”), and later they sing it together. 45

Writing Little Women gave Alcott the opportunity to immortalize some aspects of her life while concealing others. It would take over a century for readers to learn just how difficult and troubled her real life was. As Reisen has put it, “Her life was no children’s book.”46 But out of that life grew her tremendously successful book for children, which owed its popularity almost entirely to how much it seemed to resemble real life and real people. No wonder Alcott felt, as readers devoured the two parts of Little Women and wrote her countless fan letters, that they just might devour her as well.