CHAPTER SIX

MODEL #3: THE CIRCLE OF CONFLICT

BACKGROUND OF THE CIRCLE OF CONFLICT MODEL

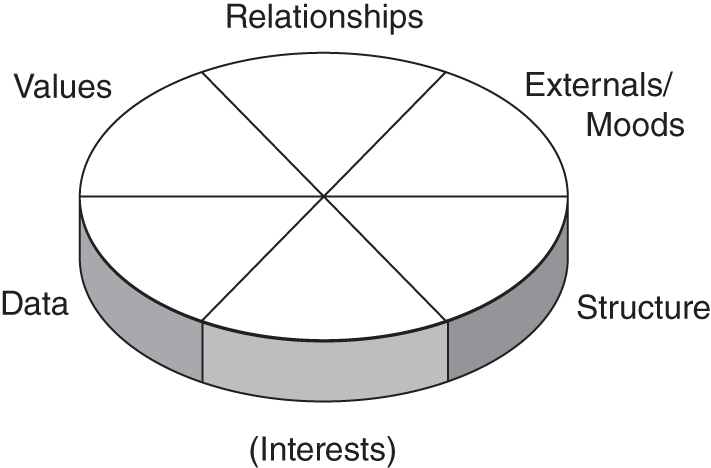

The Circle of Conflict model was originally developed by Christopher Moore at Collaborative Decision Resources (CDR) Associates of Boulder, Colorado, and is a key model used by CDR in the training of mediators. This model appears in Moore's seminal mediation book, The Mediation Process,1 and has been adapted with permission here. The version presented here is the adapted version.

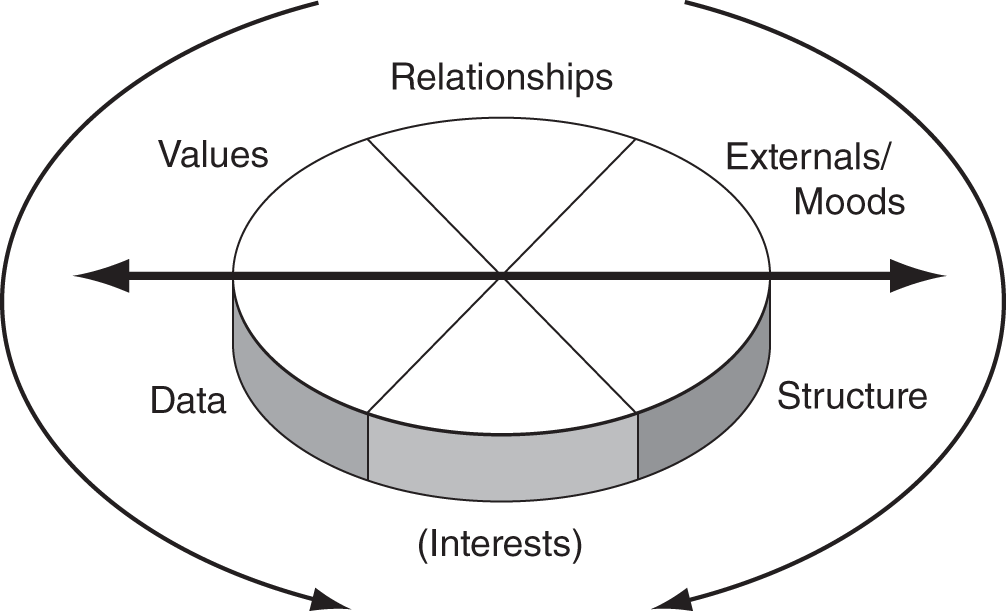

The Circle of Conflict, as a model or map of conflict, attempts to categorize the underlying causes, or “drivers,” of the conflict situation that a practitioner is facing, offering a framework to diagnose and understand the factors that are creating or fueling the conflict. After offering a way to diagnose the causes of the conflict, the Circle then offers some strategic direction on ways a practitioner can move the conflict toward resolution.

DIAGNOSIS WITH THE CIRCLE OF CONFLICT

From a diagnostic point of view, the Circle of Conflict model postulates that there are five main underlying causes, or -drivers,- to conflict. The model, along with the five main drivers, is as follows (Figure 6.1):

Figure 6.1 Circle of Conflict: Diagnosis

Relationships

|

Values

|

Externals/Moods

|

Data

|

Structure

|

|

Values

The Values slice includes all the values and beliefs held by the parties that are contributing to or causing the conflict. These include terminal or life-defining values (such as religious beliefs, ethics, and morals), as well as simpler day-to-day values employed in business or work contexts (such as the value of customer service, loyalty to the company, etc.). Value conflicts occur when the parties' differing values clash and either cause or exacerbate the situation. Because values, morals, and ethics are so important to human beings, value conflicts tend to be very heated and personal. Examples of disputes where values play a major role include conflicts based on religious and political beliefs.

Relationships

This identifies specific negative experiences in the past as a cause of conflict. Relationship conflict occurs when past history or experience with another party creates or drives the current negative situation. For example, if a customer had a problem with a bank over her bank account and later finds charges on her credit card bill that she doesn't remember making, she may blame the bank right off the bat, even before finding out that the bank had nothing to do with the incorrect charges and is perfectly willing to fix the problem. Relationship problems often lead to the forming of stereotypes, lead people to restrict or end communications with the other party, and frequently lead to tit-for-tat behavior, where one party perceives unfair treatment and retaliates against the other party; the other party then perceives this as an unprovoked attack and retaliates against the first party in some way, leading to further retaliation and conflict without end. A classic example of relationship conflict is the feud between the Hatfields and the McCoys, where members of these two families killed each other for generations in the southern United States.

Externals/Moods

This covers external factors not directly part of the situation but which still contribute to the conflict. It can be as simple as dealing with someone who “woke up on the wrong side of the bed,” or who has a medical condition such as chronic back pain, making them cranky or difficult to deal with. They can be much more involved, such as attempting to negotiate labor contracts during a recession where neither party has caused or controls the recession, but both must deal with its negative impact, leaving a negative mood in the negotiation. External or mood conflict drivers occur when outside forces either cause part or all of the problem or make a difficult situation worse. Other examples include an employee with a substance abuse problem who is difficult at work or a lawyer going through his or her own divorce while trying to represent a client in a child-support lawsuit.

Data2

Data, or information, is identified as a key driver to conflict. Data conflict occurs when the information that the parties are working with is incorrect or incomplete, or there is an information differential—one party has important information the other party doesn't have. These data problems often lead to further negative assumptions and further data problems.

Another significant data issue is the interpretation of the data, in which the parties interpret the same information in different ways. Although culturally we tend to believe that “facts speak for themselves,” in reality facts and information need to be interpreted, and this interpretation opens the door to significantly different views of the same information.

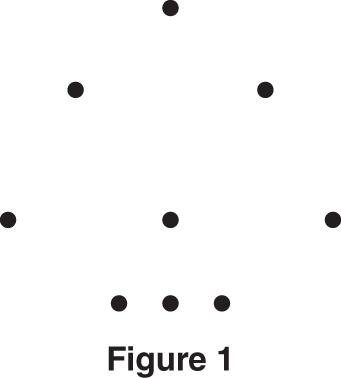

A good analogy is a children's connect-the-dots game. Numbered dots are printed on a page but form no obvious picture. By connecting the dots in the right order, a picture such as a dog or a house emerges. In real life, when we assess conflict situations we are presented with the same series of “dots” or data points, only in our case without the numbering.

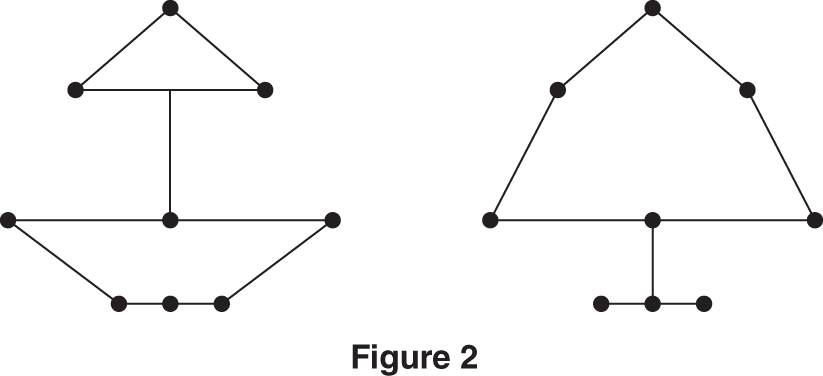

In Figure 6.2, we draw a picture by choosing to connect the dots in a particular way. The same dots, however, can be connected in different ways (i.e. different interpretations of the same information), leading to very different pictures, as in Figure 6.3.

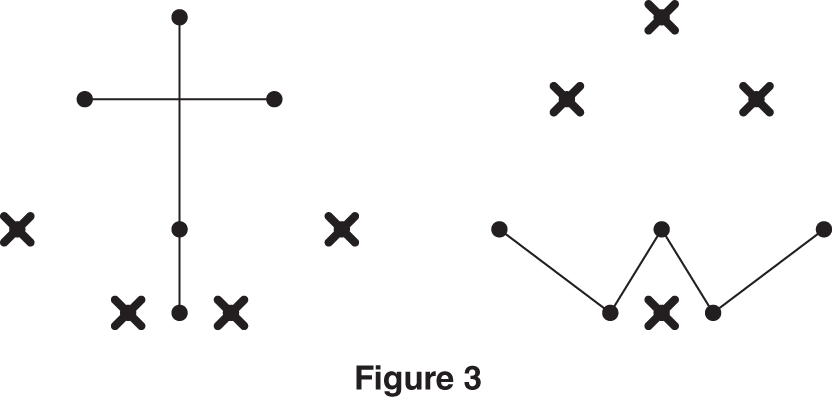

To complicate matters even further, now imagine that some dots (or data points) exist only in one picture, while different dots only exist in the other picture—each party has confidential information not shared with the other. Finally, as in Figure 6.4, it is not uncommon for a party to draw a picture that simply ignores some of the data points because they don't fit the picture the party wants to see. Completely different pictures can then be created, each of which will be completely legitimate (even seen as exclusively “right”) to the party drawing it.

Figure 6.2 Data points

Figure 6.3 Data points connected differently

Figure 6.4 Data points ignored

Structure

This covers a few different types of situations, all focused on problems with the very nature or structure of the systems we work within. Three common structural problems are limited resources, authority problems, and organizational structures.3

- Limited Resources—Having limited resources in business, for example, is a structural problem caused by the competitive free-market economy that business operates within. In other words, two companies compete (often with high levels of conflict and animosity between them) because our free-market economy mandates competition as a process that all businesses must engage in. To do otherwise would violate antitrust laws. Where limited resources cause parties to compete, this is a structural cause of conflict.

- Authority problems—Authority problems result when people try to resolve an issue but don't have the authority to actually make the decisions needed. As a simple example, when you argue with a clerk in a store over an exchange or refund, it's very unlikely that he can do what you want—as a front-line clerk he is tasked with resolving customer complaints but lacks the authority to do what you are asking.4

This lack of authority frequently contributes to the frustration and anger felt by the parties to a conflict and often leads to further escalation of the problem.

- Organizational Structures—Organizational conflict occurs when different departments or people have to work together but have divergent priorities for their respective work. The sales department of a company, for example, is tasked with selling a product or service, even if it means making promises to customers they're not sure the company can always deliver. The operations department, however, is charged with delivering the product or service in a cost-effective manner, even if it means breaching or “modifying” the promises the sales staff has made. Each has different priorities, and this can lead to structural conflict both within the company and between the company and the client.

To better understand how the Circle can be applied as a diagnostic tool, we'll apply it to the case study, looking at all five drivers.

CASE STUDY: CIRCLE OF CONFLICT DIAGNOSIS

In the case study, a number of the conflict drivers may have been at work. As we work through them, you'll note that additional information about the situation is presented; as a mediator works with, and is guided by, a particular model or map while addressing a particular conflict, she will likely uncover new facets and details about the conflict and its parties. For our purposes, we can assume that this information came out due to the practitioner exploring these areas. A basic analysis of the situation using the Circle might be as follows:

Values

There were a number of values issues at work. First, Bob believed that he was discriminated against because of his gender, that Sally specifically wanted a woman in the AS-1 position. Diane, for her part, told the mediator she believed that Bob didn't want a woman in a position of authority over him and that this was why he refused to take direction from her. Part of these beliefs came from the fact that Diane, Sally, and two other women from another area frequently had lunch together. They regularly invited Bob and other male colleagues, none of whom ever attended, characterizing these lunches as focusing on “girl things.” This reinforced the gender beliefs each of the parties held.

Relationships

Before any of the promotional issues arose, Diane and Bob had had an argument. Diane had questioned a few tasks Bob was responsible for, and this led Bob to tell Diane to mind her own business, as she wasn't his boss. Now that Diane did indeed have some functions of a “boss” in relation to Bob, Bob thought that Diane was holding that argument against him. The relationship had deteriorated to the point that there was now a harassment complaint against Diane, further impairing the relationship. In addition, Diane, Sally, and a few others had built a “social” relationship at work, something that Bob felt threatened by. This further strained and blocked Bob's relationship with Sally and Diane.

Externals/Moods

This organization had been recently turned into an arm’s-length agency and was no longer directly a part of the government. This had created considerable upheaval and change, which made everyone nervous and touchy. The office environment was one of suspicion and distrust toward “management,” which made the issues involved even more difficult. Finally, the fact that staff did not have a new collective agreement was upsetting employees across the board and probably contributed to the situation.

Data

There were a number of data issues. When the AS-1 position was first announced, Bob had assumed the promotion would be based primarily on seniority and was confident he would be promoted. In reality, seniority was not a criterion that was used, and the AS-1 role was evaluated primarily on supervisory and customer service skills. Sally was not aware of Bob or Diane's career goals and did nothing to help them plan to meet those goals. As the conflict escalated, everyone made assumptions about others' intentions, mostly incorrectly. Bob believed Sally didn't trust or like him because she was trying to eliminate communications with him. Diane believed Bob was trying to make her job so difficult she would resign the AS-1 role, so that he could have it. Bob believed that even Diane had a problem with some of the changes Sally was making. The misinformation grew rapidly.

Structure

There were a number of structural problems. First, Bob believed that Sally made these changes on her own initiative. Later, it was made clear that the head office was implementing this CL-1/AS-1 structure in all five engineering offices across the country, and Sally had no authority or discretion to change it. Second, Bob didn't understand the new roles well, in that Diane seemed to be his supervisor but didn't do his performance appraisal or any discipline. Bob couldn't see how Sally could do his performance appraisal when he wasn't allowed to interact directly with her. Diane was frustrated because she had been given responsibility for supervising Bob but little authority to address Bob's behavior - she had to go to Sally for that authority. Finally, Sally's office was next to Diane's but down the corridor from Bob's, which meant that Sally simply got to see Diane much more often than she did Bob.

As we can see, all five of the drivers were present and contributing to this situation. This is not unusual. As we will see when we look at the strategic use of the Circle, having multiple drivers in a conflict situation helps us a great deal.

Let's take a look now at how the Circle can guide the practitioner toward strategic choices based on the diagnosis.

STRATEGIC DIRECTION FROM THE CIRCLE OF CONFLICT

From a strategic perspective, the Circle can give the practitioner some guidance as to what to do with various types of conflict drivers once they are identified. To achieve this, the Circle is divided into two parts, the upper and lower half, with values, relationships, externals/moods in the upper half, and data, structure, and interests5 in the lower half. Put simply, the guiding principle for the practitioner is to help the parties stay focused below the line—on data, structure, and interests—as these areas are effective in moving the parties toward resolution. The drivers above the line—values, relationship, and mood/externals—cannot be easily “solved” between the parties and often lead to escalation in a conflict situation. Because most conflicts contain a number of the drivers identified, practitioners often have a number of different drivers to work with. Strategically, therefore, the Circle guides the practitioner to focus the conflict into the data, structure, and interest areas to help the parties most effectively understand and resolve the conflict (Figure 6.5).

By keeping the focus below the line on the model, parties have the best opportunity for collaborative work; by letting the focus stay on the value differences, the relationship problems, and the mood/external problems that the parties don't control, the conflict tends to escalate and become intractable.

Figure 6.5 Circle of Conflict: Strategic direction

Some strategies in working with data problems are:

- Have each party explain, challenge, and correct erroneous data

- Jointly assess the data

- Surface assumptions around the parties' assessment of data

- Challenge assumptions made about other parties' motives

- Jointly gather data that each party will agree to accept and rely on

Some strategies in working with structure problems are:

- Identify structural issues both parties face, and brainstorm solutions jointly

- Negotiate a ratification process if authority is a problem at the table

- Negotiate who needs to be present from both parties to resolve the issues most effectively

- Renegotiate priorities for both parties that are more compatible and workable

- Brainstorm ways to maximize use of scarce resources

By far, the interests slice is the most important area to help parties focus on. Some strategies in working with the interests of the parties are:

- Identify the full range of interests the parties have in relation to the issues they face

- Identify and focus the parties on their common interests

- Look for solutions that maximize meeting each party's interests

- Help the parties creatively solve the problems by trading low-priority interests for more important ones

Further strategies for working with interests are available in greater depth within Model #2: The Triangle of Satisfaction.

CASE STUDY: CIRCLE OF CONFLICT STRATEGIC DIRECTION

In the situation with Bob, Diane, and Sally, the Circle guides the practitioner to avoid fighting over values, relationship, or external/mood issues. Exploring Bob's view of female bosses, for example, or exploring Bob and Diane's argument prior to the promotion or even exploring how the parties felt about the collective agreement negotiations would all likely result in either escalation of the conflict, or flat denials by the parties and, eventually, impasse.

The Circle strategically guides the practitioner to focus the intervention into data, structure, and interests. Note that each of the following strategies can be followed by brainstorming or joint problem solving to help find solutions for a given issue. Presented next are some ideas on how to initiate and focus these types of discussions.

The following strategies should be done in the appropriate joint meeting, either with Sally and Diane, or with Bob and Diane.

Data

- Bring parties together to explain, challenge, and correct data problems:

- Have Sally explain the criteria for the AS-1 position and how seniority and customer service skills were weighted in the competition. Have Bob explain to Sally his career goals and what help he wants from her to achieve them. Have Sally outline how she can help Bob with that.

- Surface assumptions about each other's motives:

- Surface Bob's assumption that losing the promotion meant that his work there was not appreciated or recognized. Let Sally address this with Bob.

- Surface Bob's assumption that Sally didn't trust him or like him because she wanted Bob to work through Diane. Let Sally explain the reasons behind the decision and what degree of flexibility there is.

- Surface Sally's assumption that Bob resisted change in general, even if it was change for the better. Let Bob explain his behavior.

- Surface Bob's assumption that Diane agreed with him and disliked Sally's changes in the work team. Let Diane explain why she supported or accepted the changes.

- Surface Diane's assumption that Bob was trying to make her job very difficult, and let Bob explain his motives in how he behaved with Diane.

- Surface Bob's assumption that Diane was trying to be abusive toward him when she raised her voice or swore. Let Diane explain her frustration and feelings about this and perhaps even apologize for the behavior.

Structure

- With Sally and Bob, identify structural issues the parties face and brainstorm solutions jointly:

- Raise the fact that the AS-1 position was mandated by Sally's boss, and applied to all engineering centers across the country.

- Ask Bob to verify this at the five other centers. Let Sally talk about her degree of flexibility and where she has discretion to make changes.

- Raise the fact that Bob didn't understand his new role and how it related to Diane's role. Let Sally talk about how she sees the team working together, getting as specific as possible.

- Raise the issue that Diane had been given responsibility for Bob but has little actual authority. Let Bob identify what he would need to treat Diane as his “boss,” for all intents and purposes.

- Raise the issue that Bob feels ignored by Sally, because he isn't allowed to communicate with her. Let Sally address her intentions, and brainstorm other solutions that would work for her, Bob, and Diane.

- Surface Bob's concern that his office is farther away from Sally's than Diane's, and that this contributes to his feeling left out. Let Sally and/or Diane brainstorm ideas to improve this.

Interests

- Identify the full range of interests each person has (note that the following is a basic list, not an exhaustive one):

- Bob wants to do a good job, get a promotion and raise, have ongoing contact with his manager, be treated respectfully by Diane, and have a positive, constructive work environment.

- Sally wants an end to the problems, for Bob to accept her decisions, and to work well with Diane in a positive, constructive work environment.

- Diane wants a good working relationship with Bob and for Bob to accept her directions in the workplace.

- Focus on common interests:

- All three want a positive, constructive work environment and an end to the problems.

- All three want to deal quickly with the harassment complaint−Bob, because he wants the behavior to stop, Diane because this could affect her work record, and Sally to minimize the time spent on addressing it.

- Look for solutions that maximize meeting each party's interests:

- Bob could accept Diane's promotion and authority in exchange for Sally helping him work toward getting his own AS-1 position somewhere else in the company. This could include “acting” positions, training, etc.

- Sally could include Bob in the communications loop in exchange for Bob taking any problems to Diane before raising them with Sally.

- Diane could commit to respectful communications with Bob (as he defines them and as they fit into the harassment policy) in exchange for Bob being respectful (as she defines it) in accepting Diane's directions in the workplace.

Diagnosing the case study with the Circle of Conflict model gives the practitioner a clear understanding of the causes of the conflict, as well as a wealth of ideas for intervening that can help the parties move toward resolution.

ASSESSING AND APPLYING THE CIRCLE OF CONFLICT MODEL

The Circle of Conflict is strong as a diagnostic model, in that it proposes specific categories for understanding the dynamics that are driving a conflict without being limited to any particular substantive type of dispute. For this reason, the Circle of Conflict can be used with just about any type of conflict a practitioner may be involved in. In addition, this tool gives the practitioner a way to identify the different causes of a conflict, and helps the practitioner look beyond what appears on the surface to be the problem and begin to question the underlying or root causes.

Strategically, this model gives clear ideas to the practitioner as to what direction to take with each “type” of conflict driver. It gives clear direction to focus away from the top half of the Circle and onto the bottom three drivers, and within that to focus on interests above all. When working with the data and structure categories, it gives specific strategies for the practitioner to focus on, with an emphasis toward joint problem solving.

In terms of ease of use and applicability, the Circle strikes an effective balance between complexity and simplicity. Basically, the Circle model is simple but clear, a necessary quality for the model to be useful to practitioners.

Two additional conflict patterns that the Circle highlights can be very useful to a practitioner in diagnosing conflict:

The Values/Data Dynamic

If one party to a conflict sees the conflict primarily from a values perspective (i.e. feels that it is primarily a moral or ethical problem), and the other party sees the conflict as a data problem, an interesting dynamic takes over. The person who perceives the problem as a data problem will tend to give more and more information to the other party in an effort to convince them that they are right. The values person, of course, is very unlikely to change their mind based on more data (and are unlikely to even read the data!). The conflict is likely to escalate rapidly, with the data person accusing the values person of bad faith (“I keep giving you important and relevant information, and you just ignore it!”), whereas the values person will start to consider the data person unethical or unprincipled (“What kind of person would try to rationalize this kind of decision?!”). The real problem, of course, is that they are actually dealing with two different problems, and are unaware of this fact. When this happens, the conflict will migrate to the top half of the Circle fairly quickly, landing on the values and/or relationship drivers, which are two of the hardest to resolve.

The Structure/Relationships Dynamic

Suppose two individuals, A and B, work in different departments, and A needs a report from B to complete his work. For B, this is a low priority, but for A, it is very high. This is a structural problem, in that A has no authority to order or direct B to do what he needs. For the first few days, A will accept B's promise that he'll “get to it as soon as possible.” After a week or two goes by without getting the report from B, A will stop thinking that B's problem is a lack of time and will start to personalize it, saying to himself, “The problem isn't B's time,he's had two weeks! The problem is B; he doesn't want to help me.” Rather quickly, A and B will no longer just have a structural problem, it will become a relationship problem—and become much harder to solve.

As with all models, we are not concerned with proving that the Circle of Conflict model is “right” about the case study presented but rather asking the question, “Does it help us work with the people and the situation?” The answer is yes, as it gives practitioners a clear and simple framework for both understanding what is causing or contributing to the conflict and what might be done to move forward constructively.

PRACTITIONER'S WORKSHEET FOR THE CIRCLE OF CONFLICT MODEL

- Diagnose and list the causes of your conflict situation using the five drivers: values, relationships, moods/externals, data, and structure (Figure 6.6).

- Develop a full list of each party's interests (wants, needs, fears, hopes):

Figure 6.6 Circle of Conflict worksheet

| Party A: | Party B: |

| Interest: | Interest: |

| • | • |

| • | • |

| • | • |

| • | • |

| • | • |

- Guide the intervention to focus on the bottom half of the Circle—data, structure, and interests:

| Data Strategy Questions: | |

| What data are different between the parties? | |

| What data can be collected jointly? | |

| What “connect-the-dots” assumptions or interpretations are the parties making about the data? | |

| What assumptions about other parties' motives are being made? | |

| What data substantiate the assumptions? | |

| What data contradict the assumptions? | |

| Other data issues: | |

| Structure Strategy Questions: | |

| What limited resource problems are the parties facing? What other resources can the parties bring to the table? | |

| Where is lack of authority a significant problem? What process can be used to address the lack of authority? |

|

| How divergent are the parties' priorities? What is the process for aligning the parties' priorities? | |

| Other structure issues: | |

| Interest Strategy Questions:6 | |

| What is the full range of the parties' interests? | |

| Given the parties' full range of interests, what are their common interests? | |

| Where can the parties “dovetail” their interests? | |

| Other interests issues: | |

Other strategies suggested by the Circle of Conflict:

- If the dispute is stuck in values:

- Have the parties share information about their values.

- Look for common or “superordinate” values the parties share. Focus on the common values as a way of minimizing the competing values.

- Separate areas of influence, so that one party runs the finances and the other handles operations, for example.

- Agree to disagree on values, and shift discussion to the parties' interests, that is, what they want, given that they have competing values.

- Gently uncover incongruous values held by a party.

- If the dispute is stuck in negative relationship issues:

- Take a “future focus,” and help the parties look at what needs to change to improve the situation—a past focus tends to focus on blame.

- Help the parties develop a vision of the ideal future and brainstorm with them how they can get there.

- Find out specifically what each party needs to see from the other party to change their perception of them. Help each party commit to making those changes.

- Focus the parties on their interests and what they need to get past the relationship issues.

- Help them agree to small steps that will build trust, and begin to change the parties’ perceptions of each other in the relationship.7

- If stuck in externals/moods:

- Acknowledge the external issues that the parties don't control, and focus them on what they do control and/or influence.

- Find a way to bring the people who do control the external influence into the negotiation, if appropriate.

- Help each party plan to deal with the external issues separately, and limit the negotiations at the table to the issues between the parties.

- Reconvene when the mood or external issue has diminished.

- Focus the parties on their interests, given that they don't control the external issues.

ADDITIONAL CASE STUDY—CIRCLE OF CONFLICT

An additional case study follows, along with how the Circle of Conflict could be applied by the practitioner.

Case Study: The Spanish Estate

The conflict was caused by the passing of an elderly, first-generation Spanish immigrant. He left four children—the oldest daughter, Anne; the second oldest, Maria; the third oldest, Joe; and the youngest, Angie.

In the father's final years he needed care, and only the second oldest, Maria, took on the task, moving into the father's house with her husband and two kids. She took care of him for over seven years and, apparently angry that she was the only one caring for the father, she restricted the visiting rights of her siblings. The other three children filed a lawsuit demanding, and getting, more access to spend time with the father. The son, Joe, was most estranged from the father, although he visited once in a long while. Relations between Maria and all three of her siblings continued to deteriorate, culminating in the disappearance of an expensive set of tools that Joe had acquired and stored in the father's garage. Maria had information that the tools had been stolen by Joe for the insurance money, but Joe denied this and sued Maria in small claims court, saying that Maria sold the tools. This dispute was still ongoing.

The father died, leaving a will that split everything equally between the four children. The estate comprised the father's house, four properties back in Spain (some owned communally with other relatives), the parents' jewelry and other personal effects, and about $50,000 in cash. Maria claimed some of the jewelry was given to her by the mother (who had died nine years before), along with a statue of the Virgin Mary. The other three disputed the claim that this had been given to her. Other jewelry was simply missing; Maria claimed the parents had lost it, whereas the siblings thought Maria had taken it. Finally, the father had made various loans to all four children, with no records or provision that they needed to be repaid to the estate. The children had stopped speaking to each other, and Anne, Joe, and Angie filed a lawsuit to freeze the estate until an agreement could be reached.

Circle of Conflict diagnosis: The Spanish Estate

Values

In this case, there were a number of values drivers at play. In traditional Spanish culture, according to the three children, the oldest sibling was entitled to make decisions for the whole family. When the oldest daughter tried to do this, Maria ignored her and said that in North America this traditional approach wasn't acceptable. The three children were offended that Maria was renouncing part of their shared cultural past. In addition, Maria was very religious, and because she believed that Joe had stolen the tools stored in the father's garage, it was hard for Maria to even speak to Joe—she viewed him as nothing but a liar. Finally, Maria saw that she was the only one who had stepped forward and cared for the father; according to her, she had had to step into the eldest child's role, according her the status traditionally afforded to the eldest. The other three rejected this.

Relationships

There were a number of relationship drivers involved. When Maria moved in with the father, according to the other three, she refused to let them see him. This got worse and worse, and about three years before the father died, they filed a lawsuit against Maria for access and visitation with the father. After both sides spent money on lawyers, there was a negotiated agreement for access. This episode effectively ended communication between the three siblings and Maria.

Externals/Moods

There were a few external/mood drivers worth noting. The family was still intimately involved and connected to the extended family in Spain, and both Maria and the three siblings had family members that they spoke with in Spain. In addition, these family members tended to talk about the conflict with others in the extended family, “stirring it up,” and fueling the conflict in North America.

Data

There were a number of data issues in this case. The primary one was the value of the father's house. This was a large house in a significant state of disrepair. The children had valuations done by two local real estate agents, one suggesting listing the property at $375,000, the other at $425,000. There were wildly different assessments for the cost of needed renovations, none of them from licensed contractors. In addition, Maria claimed that the foundation was cracked and that this alone would cost $70,000 or more to repair. Joe claimed that he had watched the home sales in the area and said that if it were fixed up, due to its size, it would sell for over $500,000, maybe even $550,000. Another data issue was the value of the properties in Spain, particularly important because the siblings did not want to sell them but simply to value them and then divide them up. A final data question was the level of the father's competency in his final two years. Had he been competent enough to make the financial decisions that he made, which apparently benefited Maria?

Structure

There were two key structure drivers involved. First, Maria lived in the father's house and controlled access to its contents, to inspectors, etc. When the father was alive, the other siblings claimed that she had controlled his finances as well, by virtue of the fact that she lived there. The other structural problem was that property ownership laws in Spain were different from local laws, and if an agreement were reached in this jurisdiction, it would not necessarily be binding on properties in Spain. Finally, the whole estate was worth somewhere around $600,000, and if the siblings litigated all of the issues, much of that could be spent on legal fees before the siblings received any of the money.

Circle of Conflict worksheet: The Spanish Estate

This is how the Circle of Conflict worksheet for this case might look:

Circle of Conflict Strategic Direction: The Spanish Estate

The Circle guides the practitioner to focus on the bottom part of the Circle, dealing with data, structure, and interests. Following these guidelines, a worksheet for this case might look like Figure 6.7:

Figure 6.7 Spanish Estate worksheet

| Data Strategy Questions: | Possible Intervention Action: |

What data are different between the parties?

|

|

|

|

| What data can be collected jointly? |

|

What “connect-the-dots” assumptions or interpretations are the parties making about the data? What assumptions about other parties' motives are being made?

|

|

What data substantiate the assumptions?

|

|

What data contradict the assumptions?

|

Reality test the parties, by:

|

| Other data issues: |

|

| Structure Strategy Questions: | Possible Intervention Action: |

What limited resource problems are the parties facing? What other resources can the parties bring to the table?

|

|

Where is lack of authority a significant problem? What process can be used to address the lack of authority?

|

|

How divergent are the parties' priorities? What is the process for aligning the parties' priorities?

|

|

| Other structure issues: |

Interests:8

| Party A: Three Siblings | Party B: Maria |

|

|

|

|

Common Interests

Both parties want some or all of the following:

- Want fair split of whole estate

- Want to honor parents and their legacy

- Want parents' hard work to earn money honored, not squandered by the children on lawsuits

- Want everyone to get their fair share

- Want to spend as little on lawyers as possible

- Want to stop fighting

- Want to stop damaging the family relationships any further

- Want to look reasonable to extended family

Other Strategies:

- What are the superordinate values, such as honoring the father's memory, that they can focus on?

- What do they want from family relationships in the future? What can they do today to assist with that? (This is an example of taking a “future focus.”)

- What interests dovetail effectively for trade-offs in the negotiation?

- How can each party recognize what the other has been through, even if they don't agree on the choices made?

- All siblings have a common experience, having lost their father. How might recognizing this help them work a bit better together?

Epilogue of the case study: The Spanish Estate

The mediator focused the parties on the drivers below the line, and they reached agreement quickly on:

- The Spanish properties: It was agreed to remove them from the North American settlement and to deal with them over in Spain, with the stated agreement that the value, however agreed upon by them all, would be shared equally four ways. This reduced the complexity and left the issue to be addressed under Spanish rules and law.

- The house: It was agreed that Maria could buy the house but only if she paid fair value. The process for establishing fair value was explored in detail, including the obtaining of two appraisals by qualified appraisers. After much discussion and looking at the time and expense, the three siblings finally decided that they would accept $440,000 for the house if offered; if Maria wanted it for that price, she could have it. This was the equivalent of getting $462,000 on the open market and having to pay a commission, and they felt they could accept that. Otherwise, it would simply be sold and split equally. Maria spoke with her husband and decided that although it was more than she wanted to pay, to keep the home in the family she would buy it for that amount.

- The personal effects: It was agreed by the siblings in caucus that there was no way of ever finding out if Maria had been lying or not, so to help end the fighting they would simply divide the personal effects that were available. Maria and the siblings agreed that they should each choose one item in order of birth—Anne first, then Maria, then Joe, and then Angie. This honored the eldest with the first choice, and Maria accepted this. They all made their choice and agreed to the same process with all the rest of the contents of the house.

By keeping everyone focused below the line, and by reinforcing the common interests throughout, the parties were able to stay on track and reach an acceptable resolution.

NOTES

- 1. Christopher Moore, The Mediation Process, Third Edition (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass), 2003.

- 2. The data slice is expanded and developed in Chapter 7, the Dynamics of Trust model, specifically around attribution theory.

- 3. Geographical constraints, such as managing staff in remote locations or over wide geographical areas, also cause structural conflict. Because this particular driver is less common than the three listed previously, the focus here is on the most common examples.

- 4. This situation, often called “responsibility without authority,” is very typical in organizations and causes or fuels a great deal of conflict in the workplace.

- 5. Interests, for Moore and for this model, are defined as a party's “wants, needs, hopes, or fears.”

- 6. For in-depth strategies for interests, see Model #2: The Triangle of Satisfaction.

- 7. See the Dynamics of Trust model to explore the trust issues in greater depth.

- 8. The interests analysis can be deepened by working with the Triangle of Satisfaction in Chapter 2, as well.