CHAPTER 2

HOLLYWOOD

THE LEGEND BEGINS

“HOLLYWOOD,” wrote one contemptuous critic in 1923, “is wherever the young and the ignorant expect to get the triumph without the toil, the reputation without the virtues, the fame without the achievement.”1 If the young Howard Hughes had left home intending to achieve instant recognition, he could not have selected a better place.

He and Ella took up residence late in 1925 at the Ambassador Hotel, the same luxurious manor where Hughes’s father had stayed on visits to the Coast. The Ambassador was situated in its own tropical park far from downtown, only a short walk from the Cocoanut Grove nightclub and near the movie studios that attracted Hughes. He had vague ideas about producing movies. Hughes Sr. had run with the movie crowd, and after his death, Howard’s only relief from the oppressive gloom at Uncle Rupert’s had been occasional visits to the Goldwyn Studios in Culver City. In the shadow of the sets, amid the clutter of cameras and props, the shouts of actors and directors, and the general confusion of the place, Hughes watched in fascination as silent movies were made.

For his first film venture, Hughes teamed up with Ralph Graves, an actor whom Hughes Sr. had once placed on the tool company’s payroll. Graves had acquired a story called Swell Hogan that he was convinced would make a great movie. Hughes invested about sixty thousand dollars and let Graves do the rest. The finished product was so bad it was never released.2 For all its opportunity, Hollywood also had its pitfalls, and Hughes was pressured by his family, notably Rupert, to abandon movies lest he squander his inheritance. Their opposition made him all the more determined to succeed.

On his next try, Hughes was more fortunate. The director was Marshall Neilan, an old friend of Hughes Sr., and the film, a comedy called Everybody’s Acting, was not only well received by critics, but made a modest profit. California began to seem more permanent. Hughes and Ella moved out of the Ambassador and into a spacious Spanish-style house at 211 Muirfield Road in the Hancock Park section, where many of the movie people were settling down. The back of the house looked out across the fairways of the Wilshire Country Club, where Hughes played golf. The verdant landscape, thick with plants and trees, sheltered the house from the semitropical sun. First leasing the house, Hughes eventually bought it for $135,000. As further evidence of his desire to stay in California, he amended the charter of a tool-company subsidiary, the Caddo Rock Drill Bit Company of Louisiana, to allow it to make movies as well as lease drill bits. Caddo thus became the vehicle for all his early films. Offices were established in the Taft Building at Hollywood and Vine. To oversee Caddo’s Hollywood operations, Hughes picked Noah Dietrich, a stocky, gruff-talking former accountant and semiprofessional racing car driver he had hired late in 1925. The son of a poor Wisconsin minister, Dietrich was sixteen years older than Hughes and had worked as a bank teller, auditor, and certified public accountant. Starting as Hughes’s personal financial adviser on the West Coast, Dietrich gradually received more assignments of an administrative nature from his youthful employer and, a shrewd and ambitious man, he gladly accepted the new role. He was cut out for more than balancing Hughes’s checkbook.

Notwithstanding the success of Everybody’s Acting, nobody took Hughes seriously as a moviemaker except Hughes himself. To most, he was an amateur destined to be devoured by the charlatans and hucksters of Hollywood. Yet the twenty-one-year-old Texas millionaire continued to confound them. In the fall of 1926, he had another success. Lewis Milestone, an iron-willed and talented Russian-born director, had broken bitterly with Warner Brothers and refused to report for work. When the studio sued, seeking $200,000 in damages, Milestone moved to escape both his contract and the judgment by submitting to the claim and then filing for bankruptcy. Inevitably, “no other studio would hire him,” and Milestone was preparing to go to Europe for work when he received a mysterious call from an intermediary of a wealthy producer who was looking for a director.3 Milestone met with Neil S. McCarthy, a Los Angeles lawyer representing Hughes’s interests in California, and was signed to a three-year contract by Caddo, a deal that eventually paid off for everyone. The film was Two Arabian Knights, a comedy set in the trenches of the Western Front about a feuding sergeant and a private “who play out their miniature war against a world-war background.”4 Costing five hundred thousand dollars, it was a grand departure from Hughes’s earlier low-budget films and a spectacular box-office success in 1927-28. It made stars of the two leading men, Louis Wolheim and William Boyd, later more popular for his movie and television role as Hopalong Cassidy, and launched Milestone on a great career that included All Quiet on the Western Front and Of Mice and Men. For his work in directing Two Arabian Knights, Milestone won an Academy Award in 1928, the second year of the awards.

Beyond his role as financier, Hughes played little part in the award-winner, and the accolades properly fell on the cast and director. To Hollywood, Hughes was still a neophyte, “the sucker with the money,” as Ben Hecht would later call him facetiously.5 He only occasionally visited the set and even then, according to what is probably an apocryphal story by the film’s leading lady, Mary Astor, he “couldn’t understand where ‘the fourth wall’ was.”6 This was a gross misjudgment. Whatever others might think of his ability, Howard Hughes was quietly absorbing the technical side of filmmaking. In his next effort, he would step out of the shadows.

Never one to think small, Hughes had in mind nothing less than an epic, a movie that would celebrate on a grand scale the deeds and valor of First World War airmen. It was a subject close to his heart. Always fascinated by airplanes, he had learned to fly and by 1928 he was an expert pilot. Many an afternoon was spent making lazy circles over Southern California in his snug Waco, swooping low over Malibu Beach, reveling in the sense of freedom that only flying afforded him. Hughes had long admired the Royal Air Force aces and he wanted to portray their exploits on film. His director friend Marshall Neilan had supplied a fitting title—Hell’s Angels.

Neilan agreed to direct. A team of scriptwriters was put to work on a story. Ben Lyon and James Hall were placed under contract to play the roles of two brothers who fall in love with the same girl, played by a statuesque Norwegian blonde, Greta Nissen. Neilan, however, soon had a falling-out with Hughes, who had strong opinions on how the movie should be shot. So Hughes borrowed director Luther Reed, an aviation enthusiast and former aviation editor of the New York Herald Tribune, who was under contract to Paramount. But Reed was no more able to get along with Hughes than Neilan had been. Irritated by constant interference, he resigned in disgust after only two months, telling Hughes: “If you know so much, why don’t you direct it yourself?”7

Hughes did just that. On October 31, 1927, he began shooting the indoor scenes at Metropolitan Studio at Romaine Street and Cahuenga Avenue in Hollywood, and within two months had completed them. If the silent era had one great advantage for producers, it was that retakes were never required for flubbed lines. Hughes then moved into the phase of Hell’s Angels he relished above all—filming the aerial sequences.

For these, Hughes assembled props and manpower on a scale that impressed even Hollywood. He wanted the aerial shots to be realistic, and the only way to achieve that was to use actual First World War fighter planes. For months, his scouts toured Europe rounding up relics from the war—Spads, SE-5s, Sopwith Camels, Fokkers. In all, he acquired or leased eighty-seven vintage planes, giving him command of the largest private air force in the world. He spent more than five hundred thousand dollars on aircraft. To fly them, he hired war aces like Roscoe Turner and daredevil stunt pilots. A ground crew of more than a hundred mechanics serviced the aircraft. In January 1928, the airplanes and men assembled at Mines Field in Inglewood, the site of present-day Los Angeles International Airport, to begin the aerial scenes.

As Hughes watched the classic planes soaring in the blue California sky, he could not resist the temptation to take one up himself. Against the advice of other pilots, he went for a “little hop” in a Thomas Morse scout plane, a ship he had never flown before.8 Four hundred feet off the ground, he banked left and the rotary-powered Morse flipped into a “dangerous flat spin.”9 Pilots, stuntmen, and mechanics watched in horror as the airplane crashed to earth. The story was put out that Hughes crawled from the wreckage unhurt, “combing pieces of motor out of his hair.”10 Actually, Hughes was pulled unconscious from the crumpled plane, one cheekbone crushed. He spent days in hospitals and underwent facial surgery. But his face, at least according to Noah Dietrich, was never the same. Where the cheekbone had been “there was an indentation.”11 Even so, Hughes was luckier than some of his pilots. Three died in fiery accidents during the filming.

As Hughes’s air force grew, he moved operations to a more spacious location in the San Fernando Valley and continued to shoot through the summer of 1928, sparing no expense. Hell’s Angels served almost as a hiring hall for cameramen, who were forever running into fellow technicians on Hollywood Boulevard during a movieland depression and greeted with: “Are you out of work or are you on Hell’s Angels?”12 Dozens of them were kept busy shooting the same scenes over and over again to gain the realism he wanted. The sequence portraying London being bombed by a zeppelin was reshot more than a hundred times. Often this striving for effect bordered on recklessness. In one scene, a fighter plane was ordered to fly so low over stationary cameras that it actually hit one.13 Nothing deterred Hughes. He wanted the aerial scenes shot against a backdrop of puffy white clouds, but Southern California had none to offer. Hughes waited in vain. Finally, he shifted operations to northern California, where the sky might prove more cooperative. On the eve of his departure for the San Francisco Bay area, Ella walked out on him.

It had never been a good marriage. Hughes was too much of a loner to share life with another person. Besides that, he had made a miserable existence for Ella in California. He spent all his time with movie people, but refused to allow her to socialize with them. “I don’t think Howard thought they were her equal,” Annette Lummis said later. “I think he tried to keep Ella where she belonged, in the Pasadena social group.”14 Hell’s Angels was the final indignity. Making the movie was the first great obsession of Hughes’s life. He had thrown himself into the production with a zeal that excluded all else, and it was not uncommon for him to work twenty-four to thirty-six hours at a stretch. He devoted himself to it with a ruthless determination that frightened even him. “Many times,” he said later, “I thought I’d never live to see the finish.”15 With Hughes absent from Muirfield Road for days at a time, Ella felt completely shut out of his life. In October of 1928, she quietly went home to Houston for a trial separation.

Two weeks after she left, Hughes signed over his Yoakum Boulevard house in Houston to his aunt, Annette Lummis, who had been living there with her husband and growing family. Hughes did this after he learned that Annette and her husband were planning to build their own house. Even though he no longer used the place, Hughes was upset that it might be vacated, and he pleaded with Annette to stay, telling her he would give her the house and build a swimming pool in the yard if she would remain. Annette replied that she did not want a pool; she wanted more room. Hughes readily agreed to finance an addition. Faced with such an appealing offer, the Lummises abandoned the idea of moving.

It was a generous gift, but Hughes’s act had more to do with his own sentimental feeling than with concern for Annette. Within a few months, when he rewrote his will, he excluded her and all his mother’s relatives from his estate. Since he had cut his father’s side out in 1925, this meant that Hughes had no plans to leave any of his fortune to relatives. Instead, he wanted the bulk of it to go to medical research. No copy of this second will has survived, but Ella, too, was undoubtedly excluded. After their separation, they headed for a final break. Later, in November of 1929, she filed for divorce in Houston, charging Hughes with “excesses and cruel treatment.”16 He did not contest, and the divorce was formally granted on December 9, 1929.

With Ella gone, Hughes pursued his true love, the concluding scenes of Hell’s Angels. In Oakland, he found the clouds he wanted as a backdrop for an aerial dogfight, involving some forty airplanes, that would make the film a masterpiece of action cinema. Back in Los Angeles, there was one last scene to shoot. To viewers who later saw it on the screen, it was a brilliant stroke. A large German Gotha bomber, the terror of the Luftwaffe, is hit by Allied fire. The plane spins out of control, crashes, and burns, symbolizing the destruction of the Hun menace. Most viewers probably did not know as they watched the scene that a hapless mechanic had been trapped in the plane when it dived to earth.

As Hughes prepared to film the bomber scene, his pilots urged him to abandon his plan for the plane to actually spin. They thought it was too dangerous. But Hughes insisted. The plane had to spin. The movie required it. Despite the danger, one adventurous pilot, Al Wilson, volunteered to fly the mission. To produce the effect on screen of a burning plane, Hughes needed someone to lie in the fuselage near the plane’s rear to work a series of smoke pots. He found his man in Phil Jones, an enthusiastic grease monkey who had been pestering Hughes for a year to let him fly. Both pilot and mechanic were fitted with parachutes and told to bail out when the plane went into the spin.

They took their positions in the Gotha (which was actually a Sikorsky disguised to resemble the German plane) and took off. With Hughes watching from aloft in a small plane, Wilson kicked the bomber into a spin at five thousand feet and bailed out. For some reason, Jones either missed the signal or was unable to get out of the plane. The bomber screamed to earth and crashed in a plowed field. Hughes made an emergency landing near the wreck, “his propeller casting clouds of weed tops, and rushed to the burning plane to get Jones out.”17 The mechanic was already dead. Wilson’s pilot’s license was temporarily revoked by the Department of Commerce, and the Professional Pilots’ Association demanded his resignation. Hughes had a scene for Hell’s Angels that no one would ever forget.

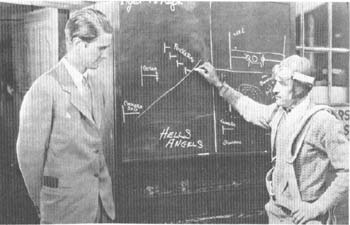

Plotting an aerial sequence for Hell’s Angels with Harry Perry, chief cameraman. The Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archives

On a Hollywood set about 1930. Philadelphia Inquirer

It was 1929. The movie was now nearly finished and, suddenly, quite obsolete. In October of 1927, Al Jolson had startled the world when he brought sound to the movies in The Jazz Singer. At first, Hollywood treated sound as a passing fad, but not the public. The public loved the talkies and demanded more. Hughes had already invested more than $2 million in Hell’s Angels, an incredible sum for those days of cheap labor and low overhead, but the sound revolution doomed it to an ignominious failure. Hughes felt he had no choice but to reshoot the dialogue scenes with sound and dub in audio for the aerial sequences.

To write a new script, Hughes borrowed Joseph Moncure March, a poet then under contract to MGM. Except for the air scenes and the final sequence, where one brother kills the other, March thought the silent version of Hell’s Angels was “depressingly bad.”18 He knew Hughes had been deeply involved in its writing, but even so, he recommended that the old script be scrapped and a new one written. Hughes agreed, and in ten days March had roughed out a script that Hughes liked. Ben Lyon and James Hall would still be perfect for the two lead male roles. But Greta Nissen, who spoke English with a Norwegian accent, would be ludicrous as the seductive English girl wooed by both brothers.

So Hughes opened his search for a replacement. Dozens of young women paraded into Metropolitan Studio for screen tests. Meanwhile, production started with orders to shoot around the leading lady as Hughes struggled “to make up his mind.”19

Late one afternoon, as the film crews turned off the lights on a set depicting an RAF mess hall in France and began packing their cameras for the day, a feisty theatrical agent, Arthur Landau, reminded the head cameraman that he had a prospect waiting for a screen test. Grumbling, the cameramen restored the lights and cameras and in walked a young woman with “almost albino blonde hair” and a “puffy somewhat sulky little face.”20 Her name was Harlean Carpenter, but she went by the stage name of Jean Harlow.

Landau had noticed her at a drinking fountain at Hal Roach studios. What caught his eye were her “high firm breasts” and her “astonishingly blonde hair, unnaturally light and brushed back from her high forehead.”21 As Landau studied her movements, he observed to a companion that he thought she was not wearing a bra.

“She never does,” answered his friend. “It’s her advertisement.”22

Convinced that he had a product of simmering sexuality, Landau had lined up a screen test with Hughes. But as the blue-eyed, eighteen-year-old stepped onto the Metropolitan set, she looked as though she were auditioning for a slapstick part in a Laurel and Hardy comedy—which she had played—rather than the femme fatale called for in Hell’s Angels. Her dress fit poorly. It was too snug around the bodice and hips. Joseph March, the screenwriter, took one look at the latest candidate and muttered: “My God, she’s got a shape like a dustpan.”23

The screen test was a disaster. Harlow was in tears half the time. At one point, she pleaded with the dialogue director, James Whale, who had become increasingly impatient with her, “Tell me, tell me exactly how you want me to do it.”

“I can tell you how to be an actress,” he answered, “but I cannot tell you how to be a woman.”24

When Hughes saw the screen test, he grimaced and told Landau: “In my opinion, she’s nix.”25

Never one to take no for an answer, Landau argued with Hughes, raving about her hair, her acting ability, her sensuality. She was the perfect combination of “good kid and tramp” to make the role a success.26

“She’s a broad and willing to put out for the fliers,” he contended. “But she knows that after she’s made them forget the war for a little while, they still have to take off and they might never come back. So her heart’s breaking while she’s screwing them.”27 Perhaps sensing the appeal of Landau’s argument, Hughes slowly came around. The agent said that Hughes could have Harlow for $1,500 a week for a six-week minimum.

“I ought to keep you around for laughs,” Hughes answered. “I’ll give her $1,500 for the whole six weeks and don’t argue.”28 Hughes insisted in addition that she sign a long-term contract with Caddo. Landau, quietly bursting with glee, consented.

As it turned out, Jean Harlow, with her “slightly lazy sexual aggression,” was just right for the part.29 With such seductive lines as the memorable “Do you mind if I slip into something more comfortable?” her career as a Hollywood sex goddess was launched, and Hughes had set a style for sex in the movies that prevailed for years. Ironically, although Hughes was credited with discovering Jean Harlow, he was personally oblivious to her sexual appeal on the screen. After Hell’s Angels, he failed to exploit his teenage siren even though a national poll ranked her seventeenth in a list of the world’s hundred best-known people. Instead, Hughes sold Harlow’s contract to Irving Thalberg at MGM for a nominal $60,000 and she went on to become Hollywood’s reigning sex symbol until her untimely death in 1937.

When Hell’s Angels was completed early in 1930, Hollywood was “gossiping, scoffing, laughing up its sleeve,” as one observer put it.30 It had become the movie colony’s favorite joke. With 2.5 million feet of film shot for a fifteen-thousand-foot movie, people chuckled about meeting a 105-year-old man who was thought to be “the only living person who could remember when Hell’s Angels was started.”31 The cost was no joke—$3.8 million—making it the most extravagant piece of filmmaking ever undertaken.32

Hughes promoted the movie on an equally extravagant scale, showing for the first time the flair for public relations that would characterize him for the rest of his life. For the California opening, airplanes buzzed Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood and stunt men parachuted onto Hollywood Boulevard. In Manhattan, Hughes took the unprecedented step of scheduling simultaneous openings at two separate Broadway theaters. He was disappointed, though, when the owners of the dirigible Graf Zeppelin refused his offer of $100,000 to fly over mid-Manhattan advertising the film. He built up curiosity by banning everyone but himself from a private showing at Grauman’s Chinese Theater. Louella Parsons quietly slipped in a side door. When Hughes discovered her inside, he ordered her out. The spunky gossip columnist refused to leave.

At its première on June 30, 1930, Hell’s Angels dazzled audiences and critics alike. It was, as one later put it, “dramatically commonplace, clumsily strung together and without clear authorship, but the aerial photography is superb, and the scenes with Jean Harlow are startlingly from another, much better picture.”33 Those two ingredients alone combined to make Hell’s Angels a box-office smash. “Nothing like it has ever happened before,” gushed Photoplay, “and probably nothing like it will ever happen again.”34 Hell’s Angels set the theme for all of Hughes’s movies—rich in entertainment, low on philosophy and message, packed with sex and action.

It also launched the Hughes legend. As the story of the movie’s genesis and production unfolded, Hughes was variously characterized as daring, independent, willing to gamble, and blessed with a Midas touch. One exuberant admirer described him as a “super-individualist… whose outstanding characteristic is his ambition and his overwhelming determination to accomplish things.”35 Some of the talk was true. Much was not. But the fact commingled with the myth to form a legend that served Hughes the rest of his life. On its face, Hell’s Angels had been an extraordinary personal achievement for Hughes. The story of his role in its production, however, began to be embellished to give him more credit than he was due. He had played almost no role in the final script, yet he was pictured not only as having produced and directed the film but as having “written” it as well.36 Others went further, calling the film a “one-man picture.”37 And then Hughes himself stepped in, with more public relations. As if Hell’s Angels’ critical success were not enough, Hughes manufactured figures showing that the movie was also an “incredible moneymaker,” yielding a profit of more than $2 million on his $3.8 million investment.38 In sober truth, according to Noah Dietrich the movie never recovered its staggering production costs, and Hughes lost $1.5 million.39 Such a loss had little effect on Hughes’s life, since the tool company regularly made ample profits to cover the losses. But to his budding legend as a financial whiz, the story of the Hell’s Angels monetary success was all-important.

Even Hollywood insiders were enthralled. The British producer Herbert Wilcox wanted to borrow Louis Wolheim, the star of Two Arabian Knights, who was still under contract to Hughes, for three days of shooting on a film he was producing. When Wilcox approached Hughes, he found the youthful producer both receptive and charming.

“He will cost you twenty thousand dollars,” Hughes said of Wolheim.40 Although the price was steep, Wilcox was so set on Wolheim that he agreed to pay. When Wilcox’s director vetoed his choice of Wolheim, Wilcox hurried back to Hughes’s Hollywood office less than an hour later to apologize for “having troubled him” and to let Hughes know the deal was off.

“You made a deal with me for twenty thousand dollars,” Hughes answered coldly. “Wolheim will report on your set Monday and be available for three days, and I want that twenty thousand dollars before he starts work!”

Wilcox protested, but in the end he paid. He later reflected that the incident probably illustrated “one of the many reasons Hughes is a multimillionaire—and I am not.”41

If Hughes exhibited a toughness beyond his years, and unusual for someone so new to the industry, he also spoke with candor and frankness, surprising for Hollywood, a town long accustomed to self-promotion by stars, directors, and producers alike. He refused to claim credit for Hell’s Angels, and was quick to admit his failures, except for the financial ones.

“Making Hell’s Angels by myself was my biggest mistake,” he confessed in a rare interview in 1932. “It would have been finished sooner and cost less. I had to worry about money, sign checks, hire pilots, get planes, cast everything, direct the whole thing. Trying to do the work of twelve men was just dumbness on my part. I learned by bitter experience that no one man can know everything.”42

At twenty-six, Hughes had apparently learned the rule of all successful executives: leaders must delegate authority. Yet in the years ahead, he would routinely disregard the lesson, making it a custom to interfere with, secondguess, and deny authority to his managers. If, as he claimed, he “went to school” making Hell’s Angels, he promptly forgot what he had learned.43

CELEBRITIES AND CENSORS

No one embraced Hughes with more enthusiasm after Hell’s Angels than the charmed circle of stars, directors, and producers who made up the heart of Hollywood’s power. They were the beautiful people, written about in movie magazines and gossip columns, and invited to all the right places. Hughes’s success with Hell’s Angels made him an overnight favorite among them—especially with the women. If it was not his power and money they found attractive, it was his dark good looks. The somewhat spindly looking youth who had invaded Hollywood five years earlier had matured into a handsome young man. He was still thin and spare, yet his face had filled out, and he had the look of an older man. With his dark eyes and hair, he was fit for a starring role in one of his own movies.

But even in success, Hughes remained shy, “self-conscious with strangers and reticent with intimates.”44 At parties, he was hopelessly out of place, as one writer noted: “When standing he inclines his head out and down and looks at the ground. Seated, he clasps his hands between his widespread knees and stares at his knuckles.”45 This self-effacing, almost timid public image seemed at odds with the legend that had begun to grow about him—the fearless pilot, the daring driver whizzing through Southern California, the gambler whose stakes were his own fortune. For one who supposedly abounded in courage, Hughes appeared oddly frightened and subdued around others. The contrast only made him more intriguing. To Hollywood, he was a “man of mystery.”46 He never wore a watch, he kept odd hours, he hated to be photographed, and he avoided large parties, preferring small, intimate get-togethers in private homes.

Although Hughes was shy, uncomfortable around strangers, and eccentric, these characteristics, which would become more extreme as the years passed, hardly set him apart in Hollywood. The movie colony had more than its share of eccentrics and misfits. Still, the phobias instilled by his mother, his neurotic fear of illness and disease, were maturing, and they now were compounded by a growing obsession with the details of his work, a compulsive striving for perfection in projects large and small. In the 1920s, these traits were part of Hughes’s appeal, part of his growing legend. In time, they would take on a darker meaning.

Although he disliked large parties, Hughes overcame his fears when the host was William Randolph Hearst. The lord of San Simeon gave the most memorable parties of his time, and Hughes was a frequent guest. Invitations were extended shortly before the weekend. Guests were asked to be at the Glendale railroad station at 7:35 P.M. on Friday. There, Hearst’s train waited to carry them through the night to his 350,000-acre estate overlooking the Pacific, midway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. There were two sleeping cars and a diner, plentifully stocked with liquor. A strict teetotaler, Hearst forbade his guests to bring liquor into La Casa Grande, although he compromised by serving two cocktails at dinner. On these trips, Hughes found himself in the company of Hollywood’s elite: Irving Thalberg, Norma Shearer, Charles Chaplin, Louis Mayer, Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks. Early in the morning the train arrived at San Luis Obispo, where a fleet of limousines waited to chauffeur the guests the final leg to San Simeon. Perched high above the ocean, bathed by soft breezes, Hearst’s castle was a make-believe setting for a weekend retreat. Hearst had furnished and adorned the mansion, guest houses, and grounds with priceless antiques collected around the world. On the grounds, zebras, giraffes, emus, camels, and yaks wandered freely, all part of W. R.’s private zoo.

Birthdays meant a lot to Hearst. He always gave a “sultanesque party” to observe his own.47 He and Marion Davies, his blonde live-in actress, invited scores of people to attend and they were expected to arrive in costumes reflecting a preannounced theme. One year it was the Civil War, and Hollywood’s finest turned out dressed in blue or gray and delighted in shoving one another into the outdoor swimming pool graced by the facade of an authentic pre-Christian Greek temple. Hughes observed the rules of the game. For the year of a circus theme, he came as a “knobby-kneed lion tamer.”48 At a Tyrolean party, Hughes looked like a bona fide native of that region as he posed, smiling, for photographs with fellow partygoers wearing short pants, an Alpine hat, and a short brocaded jacket.

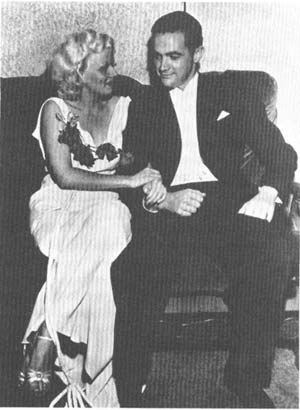

A night out with Jean Harlow, 1934.

Bettmann Archive

William Randolph Hearst’s Tyrolean Party, 1934. Left to right around table: Eileen Percy, Kay English, the designer Adrian, Richard Boleslawsky, Mrs. Boleslawsky, Hughes, Marion Davies, and Jack Warner.

United Press International

Hughes got along with Marion Davies. To her, he was a “big, awkward, overgrown country boy” who was polite, nice, and affable.49 Marion also liked Howard because “he didn’t talk too much.”50 They both loved ice cream, and after dinner engaged in spirited “ice cream races” to see who could eat the most.

“Nobody can outdo me,” Hughes joked with Marion.51 From young adulthood on, Hughes had adopted the diet of an unrestrained seven-year-old, and ice cream was near the top of the list of his favorite foods. Still, when he and Marion had finished their “race,” he was “green” from overeating and she never seemed to have had enough.52

It was Marion who introduced Hughes to Billie Dove, the first in a long line of actresses with whom he would be romantically linked. Billie, an attractive brunette, had excited New York at the age of sixteen as a Ziegfeld Follies girl, and went on to screen stardom in the silent era. After the breakup of his marriage with Ella, Hughes and Billie were frequent companions, although both maintained other relationships. While Hughes engaged in an affair with the promising actress Carole Lombard, Billie renewed a friendship with the dark, handsome George Raft, whom she had dated earlier in New York. The Dove—Raft relationship ended abruptly. After a night on the town, Raft and Billie retreated to a “gorgeous suite” at the Ambassador Hotel.53 Shortly after, a call came through from one of Raft’s lookouts in the lobby, saying that Howard Hughes was down there and that Billie was Hughes’s girl. This was news to Raft, who would never have gone near his old flame had he known of her association with the millionaire producer: “The last guy in the world either of us wanted to cross was Howard Hughes.”54 Saying good-bye to Billie, Raft slipped out of the hotel by way of a service elevator. Billie later starred in two Hughes movies, Cock of the Air and The Age for Love. Hollywood buzzed with rumors of their impending marriage, especially after Hughes financed Billie’s divorce from the director Irving Willatt in 1931. But the romance soon fizzled. Hughes once again was unable to forge a lasting relationship.

Hollywood continued to lionize him, but he still kept the movie capital at arm’s length. If as a boy he had felt some pangs at not being accepted by his peers, as his mother’s letters suggest, he was now a confirmed loner, an outsider by choice who in 1932 told an interviewer asking about the future of motion pictures: “I don’t know anything about [it]…. Let the big guys do the talking.”55 Sometimes Hughes reveled in this role of maverick, as in the summer of 1931 when he threatened to make a movie exposing Hollywood’s sins. To be entitled Queer People, the movie’s heroines would depict a world “insistently immoral and the scene of their depravities [was] to combine the worst features of Sodom and Gomorrah.”56 Hughes went so far as to hire Ben Hecht to write a script and Walter Winchell to play the part of a reporter “with a nose for glamorous living” before dropping the project.57

After Hell’s Angels, Hughes returned to his earlier role as producer and let others do the directing. He produced two motion pictures while the aerial epic was under way—The Mating Call and The Racket—and then five more films in the year following Hell’s Angels: The Age For Love, Cock of the Air, Sky Devils, The Front Page, and Scarface. The last two were the best of the lot, thanks to talented directors. Lewis Milestone directed the screen version of the Ben Hecht - Charles MacArthur play about Chicago newspapermen. Hughes stayed off the set, letting Milestone have a free rein, except for vetoing two relatively unknown actors whom Milestone wanted to use in leading roles. One was James Cagney, whom Hughes called a “little runt.”58 The other was Clark Gable, rejected by Hughes because “his ears make him look like a taxi-cab with both doors open.”59

In Scarface, a thinly veiled story of Al Capone and his Chicago mob, Hughes sought to cash in on a national fascination with gangsters. To direct the film, he turned to one of his adversaries, Howard Hawks. Hughes had filed a lawsuit in July of 1930 in New York charging that portions of Hawks’s movie Dawn Patrol had been lifted from Hell’s Angels. The incident marked a further deterioration in relations between Hughes and his uncle Rupert. The script for Dawn Patrol was written by John Monk Saunders, who was then married to Rupert’s stepdaughter, Avis. Ordinarily, Hughes would never have anything to do with someone he suspected of trying to take advantage of him. Yet this time he put aside those feelings to woo Hawks, a director whose work he admired. It would take all his charm. Hughes selected a golf course for the peace talks. One morning as Hawks was about to tee off at the Lakeside Country Club near Universal Studios, the club’s golf pro rushed up with a message.

“Howard Hughes is on the phone and wants to come out and play golf with you.”

Hawks was speechless. The man who was suing to stop his film wanted to play golf with him? He bristled.

“Tell him I don’t want to play golf with him.”

“Why?”

“The son of a bitch is suing me, that’s why.”60

A few minutes later the pro returned with another message—Hughes had agreed to drop the lawsuit and was on his way to the golf course. They played eighteen holes. The story goes that Hawks beat Hughes, who was an excellent golfer, and that before the day was over had agreed to make Scarface.

As usual, Hughes spared no expense on the film, which he wanted to be the last word in gang pictures. He gave Hawks a huge budget and stayed out of his way. The director hired Ben Hecht to write a script. He discovered an actor named Paul Muni playing in Yiddish theater in New York and signed him to the lead role. George Raft was to play the part of Scarface’s bodyguard. Among the supporting actors was a young Britisher, Boris Karloff.

The finished film pleased everybody who had worked on it but it was so loaded with violence and bloodshed, not to mention overtones of incest between Scarface and his beautiful sister, that when it was submitted to Hollywood’s censoring agency, the powerful Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, the agency rejected it, demanding substantial cuts and a new ending. By most accounts, the original ending was a brilliant stroke: trapped by police, Scarface degenerates into a blithering coward and is gunned down by police. The new ending demanded by the censors was to show Scarface being tried and executed by the forces of law and order. Hawks was bitterly opposed to the suggested changes, fearing that they would emasculate the film. But Hughes agreed to the revisions. The watered-down version earned the movie a Seal of Approval. Yet when Hughes tried to première the movie in New York, the state’s Board of Censors refused to let it be shown. Hughes exploded, issuing a statement that liberal defenders of freedom of expression found heartwarming:

It has become a serious threat to the freedom of honest expression in America when self-styled guardians of the public welfare, as personified by our film censor boards, lend their aid and their influence to the abortive efforts of selfish and vicious interests to suppress a motion picture simply because it depicts the truth about conditions in the United States which have been front page news since the advent of Prohibition.

I am convinced that the determined opposition to Scarface is actuated by political motives. The picture, as originally filmed eight months ago, has been enthusiastically praised by foremost authorities on crime and law enforcement and by leading screen reviewers.

It seems to be the unanimous opinion of these authorities that Scarface is an honest and powerful indictment of gang rule in America and, as such, will be a tremendous force in compelling our state and Federal governments to take more drastic action to rid the country of gangsterism.61

Hughes’s fighting stand won him many admirers. The New York Herald Tribune praised him for being the “only Hollywood producer who has had the courage to come out and fight this censorship menace in the open. We wish him a smashing success.”62 With six hundred thousand dollars tied up in a production that had not returned a penny, Hughes had little choice but to fight. He filed a series of lawsuits, first in New York and then in other states, for the right to show the movie. After winning the case against the New York censors, he restored the cuts and original ending and released Scarface in March of 1932. With so much in its favor, Scarface was a splendid success, another jewel in Hughes’s crown.*