CHAPTER 10

RETREAT

TWA V. HUGHES

NINE days after the voting-trust agreement was signed, Hughes and Jean moved out of their separate bungalows at the Beverly Hills Hotel and into a rented mansion in the hills of San Diego County a hundred miles south of Los Angeles. Ever since their wedding, Jean had pressed for a house where they could “live together as man and wife.”1 Even though theirs apparently had been a marriage of convenience, Jean had been rankled by Hughes’s insistence that they live apart. Now he abruptly gave in. On December 24, 1960—Hughes’s fifty-fifth birthday—they took up residence in a $2,000-a-month estate ringed by a fence and patrolled by Hughes’s guards near the secluded village of Rancho Santa Fe. For the first time in their four-year marriage, Jean Peters and Howard Hughes were living together under the same roof.

They were not living alone, of course. The usual retinue of aides, cooks, waiters, couriers, and “third men” whom Hughes had come increasingly to depend on at the Beverly Hills Hotel came south, taking up residence at the Inn in the village center of Rancho Santa Fe, a few minutes’ drive from the Hughes house. John Holmes and Roy Crawford were the senior aides and spent much of their time in the house itself. Their schedules called for them to alternate every four days, but Hughes often kept one of them on the job for as long as two weeks at a time.

Back in New York, TWA’s lenders were luxuriating in the afterglow of the Dillon, Read triumph. The Hughes era at TWA was definitely past, or so it seemed. With the signing of the voting-trust agreement on December 15, only the formalities remained. Even so, Hughes managed to wring the maximum of tension and drama from what should have been a ceremonial affair.

On the morning of December 28, representatives of the lenders assembled at the Farmers Bank, in Wilmington, Delaware, where Raymond Holliday was expected to sign over Hughes’s stock to the control of the lender-dominated voting trust. But at the appointed hour, Holliday was not there. Instead, he telephoned, reporting matter-of-factly that he was still in his New York hotel room awaiting authorization to go to Wilmington. The startled lenders warned Greg Bautzer that they would go to court if Hughes backed out this time.2 Bautzer, mystified, tried to reassure them that Hughes had every intention of completing the deal. All day the lenders waited and by evening, with Holliday still in absentia, they were certain that collapse was imminent.

The next morning Holliday called again. He was on his way to Wilmington, but still without authority to transfer the stock. Bautzer, meanwhile, was having the usual trouble reaching Hughes, and tempers were short all around. If the documents were not signed within thirty-six hours, the end of the last business day of 1960, a new set would have to be drafted and approved by all parties.

On Friday, Bautzer reached Hughes and got his approval for the stock transfer. Executing the documents in Wilmington, Holliday hurried back to New York to sign the loan agreements before the deadline expired. At three o’clock on December 30, Holliday entered the elegant, sea-green conference room of the Chemical Bank. But he refused to sign, protesting that he needed a lawyer to review the voluminous documents. To the lenders, it was clearly another Hughes stall. Bautzer was of no assistance either. Calling his suite at the Hampshire House, the bankers learned that Bautzer had been admitted to Roosevelt Hospital, a possible heart-attack victim.

Left alone to face the lions of Wall Street, Holliday paced the Chemical’s conference room as some thirty-five representatives of banks, insurance companies, and investment houses waited. Holliday appealed for a postponement. The financiers stood firm, insisting that he sign the papers. Holliday demurred and slipped into a smaller conference room to place a series of frantic telephone calls to Romaine Street. The hours sped by. Finally, at 7:15, Holliday emerged vastly relieved. Bautzer had recovered sufficiently to call Hughes from the hospital and extract the necessary authority. Dropping into a tangerine-colored leather chair, Holliday signed papers with a flourish.3 When he had finished, word was flashed to Oklahoma City to register the lenders’ names on the mortgages of TWA’s new jets. With Holliday’s signature, Hughes had averted bankruptcy—and lost something of himself. Always before, his money and power and reputation had forced others to play his game. But the TWA contest had been a banker’s game, played out on bankers’ turf. While Jean busied herself gardening, swimming in the outdoor pool, building dog runs for her pets, and doing domestic chores around the house, Hughes brooded, shut away in their bedroom. For days he sat propped up in bed, the covers drawn over his bony shoulders, silently mourning his loss and dreaming of ways to recapture his airline.

When control passed to the lenders, TWA’s new leader was, for all practical purposes, Ernest R. Breech, a retired executive who had earned a national reputation by rebuilding the Ford Motor Company in the 1940s. Unlike Hughes, whose wealth was inherited, Breech was a self-made man. He agreed to serve without pay as one of the two lender-appointed trustees of Hughes’s stock. (The other was Irving S. Olds, a Wall Street lawyer and former chairman of United States Steel.) Breech accepted the TWA assignment “out of a sense of obligation and national duty,” believing that TWA had a great future, if only it were allowed “to be like other airlines.”4 Thriving on challenge, Breech set plans in motion to reorganize TWA’s board and hire a president. Beyond that lay the enormous task of rebuilding the airline.

Sometimes referred to in the industry as “the largest unscheduled airline in the United States,” TWA had suffered grievously under Hughes.5 The tardily ordered jets had been further delayed by the financial struggle. The impoundment at Convair meant TWA would be a full year late in receiving all the 880s, and the delay had sharply eroded TWA’s position as a leading domestic carrier. By late 1960, CAB traffic reports showed that TWA’s share of the Big Four domestic passenger market had declined from 23 to 20 percent and that United Airlines was now carrying more passengers than TWA.6 Last, Hughes’s dilatory tactics had forced TWA to pay substantially higher interest for funds than its major competitors.

Even the normally friendly CAB had been alienated. The agency, which had treated Hughes royally since the early 1940s, now viewed him as a menace. Relieved when control of TWA passed out of Hughes’s erratic hands, the CAB noted, “No longer will the directors of [the tool company] be free to enforce their dictates or those of [the tool company’s] controlling shareholder on TWA.”7 The CAB was so disenchanted with Hughes that it ruled he could not reassume control of TWA without “a searching inquiry” as to whether that would serve the public interest.8

Even so, Hughes might one day have regained command. There seems to have been no doubt in his own mind that this would happen. In a memorandum to Holliday on February 20, 1961, concerning additional Convair jets that he had ordered for TWA, Hughes said he did not know how TWA could be compelled to accept the planes, but added confidently: “Most likely HTCo [the tool company] will control TWA when that matter comes up.”9 It was simply a question of conserving his resources, raising additional cash, paying off the loans, and biding his time. But Hughes was not a patient man. Nor was it in his nature to play a passive role. Only a few weeks after the voting trust was imposed, he opened a strident attack on TWA’s leaders.

When Breech announced a meeting of TWA’s directors on January 26, 1961, Hughes barred his appointees from attending and thus made a quorum impossible, so that Breech was obliged to call off the meeting. Embarrassed by this show of resistance, Breech held a special stockholders” meeting, tossed out the Hughes directors, and replaced them with men independent of Hughes’s control. When TWA announced a $100-million debenture offering, Hughes filed a formal complaint with the Securities and Exchange Commission in an attempt to block the sale, and in March when TWA decided to acquire $187-million worth of additional jets from Boeing, Hughes charged that TWA’s management had no authority to do so. Despite Hughes’s warning that the projected sale was not binding on TWA, Boeing went through with it.

Waging this phase of the struggle for Hughes was a new advocate, Chester C. Davis, the sharp-tongued head of the trial department of Simpson, Thacher & Bartlett, a prestigious Wall Street law firm. Davis had been recommended by Floyd Odium, the millionaire financier and husband of Jacqueline Cochran. He was neither as genial as Raymond Cook nor as suave as Greg Bautzer. But he was more aggressive than either. Davis was a graduate of Princeton University and Harvard Law School, but his Ivy League polish was not always evident in the courtroom. He had been born Caesar Simon in Rome in 1910, son of an Italian mother and a French-Algerian father. After his father’s death, mother and son immigrated to the United States, where she married Chester Davis Sr. and changed her son’s name to conform. After college, Davis married into the socially prominent Ferry family of Detroit and was named a trustee of the family’s charitable foundation, only to be removed by disgruntled family members who were alarmed over what they called his “failure and neglect of duties.”10 Davis had spent virtually his entire career on Wall Street, but he was hardly a typical Wall Street lawyer. “He’d fiddle around the office all day then go off to Whyte’s [a restaurant] and toss off martinis like glasses of water,” recalled a former associate. “Then he’d come back to the office and toss out ideas for his assistants to work up overnight. Nine out of ten were no good, but that tenth one would be a dilly.”11 When the chance to represent Hughes came along, Davis had been associated with Simpson, Thacher for twenty-five years and was a senior partner. Nevertheless, he recognized a great opportunity when it knocked. Resigning, he formed his own Wall Street law firm, and shortly afterward became a vice-president and general counsel of the Hughes Tool Company.

TWA now saw that Hughes, assisted by his lieutenant Davis, was still very much a problem. By questioning the airline’s right to sell debentures and to acquire aircraft, Hughes had been more than annoying; he had challenged the very authority of the voting trust itself. No one was more concerned than TWA’s latest president, Charles C. Tillinghast, Jr. A native of tiny Saxton’s River, Vermont, Tillinghast had been lured away from a secure job with the Bendix Corporation by his old friend Ernie Breech who had given him a lucrative contract and long-term financial security.

Forceful though the Hughes offensive was, Tillinghast was not intimidated. On the contrary, Hughes had gone too far this time, making a final break with the airline inevitable. Everyone now realized that Hughes, in his obsession, would give TWA no peace. As Tillinghast mulled over the situation, he picked up rumors that Hughes was preparing to file a lawsuit against TWA and the lending institutions to formally challenge the validity of the voting trust. Tillinghast and the TWA board had, for their part, authorized the Wall Street law firm of Cahill, Gordon, Reindel & Ohl to determine whether TWA could sue Hughes for having mismanaged the airline. Thus, a climate of litigation had been created. But who would strike first?

On the morning of June 30, 1961, TWA filed a thirty-eight-page complaint in United States District Court in New York, charging Hughes, the tool company, and Raymond Holliday with violating antitrust laws in the sale of aircraft to TWA. It sought damages of $105 million and a court order for Hughes to divest himself of his 78-percent ownership in the airline. Hughes had been outmaneuvered once again.

The legal battle touched off that morning would be one of the most momentous and enduring in American business history. A product of the fertile legal mind of John Sonnett, a partner in the Cahill firm, the TWA complaint was based on a novel view of antitrust law. By compelling TWA to accept aircraft provided by his tool company, the complaint alleged, Hughes had conspired to restrain trade. For all its imaginative thrusts, the complaint also had a practical side. It was aimed squarely at Hughes personally. Sonnett had concluded that Hughes would be vulnerable to a lawsuit that sought to force him to testify in court. Although he had no idea of the extent of Hughes’s mental disability, Sonnett had come across bits and pieces of suggestive evidence. There also had been several recent instances in California when Hughes had chosen to defy court orders rather than appear. Clearly, TWA’s majority stockholder was, for one reason or another, reluctant to show his face, and Sonnett was prepared to exploit that hesitancy. Hoping to force Hughes into a quick out-of-court settlement, Sonnett asked a federal judge to seal the complaint for a few days so that the parties could quietly try to negotiate a truce. The judge granted the request and the complaint was sealed until July 11, a deadline later extended to August 8.

As Sonnett had expected, the TWA complaint terrified Hughes. He instructed Davis and Bautzer to do everything possible to settle with TWA before the complaint was made public. He told Davis,

One force within me is telling me to stand up like a man and fight this thing through to the finish and prove to the world the utter hypocrisy of these claims and inflict upon the people responsible for this unjust persecution at least some of the punishment they merit…. This same voice is telling me that this fight, if it is carried through to completion, could consume the biggest part of the remainder of my productive life and could therefore interfere with the development and furtherance of my medical institution and other important creative things I would like to do before I die. This voice tells me that even though I am completely right and justified I should listen to reason rather than passion and get this thing behind me.12

The voice within Hughes that really caused him anxiety was the one telling him that TWA would concentrate all its strategy on forcing him to give a deposition. He viewed that as grossly unfair. The lawsuit would not impose “even so much as an inconvenience” on executives of the “other side,” who could “rattle off” depositions in their offices.13 But as for himself, he knew he could not leave his self-erected asylum or allow anyone from the outside to enter it. Hughes told Davis he was too sick to give a deposition. “I have not been out of bed for more than nine months. My illness is no fiction and my doctor can furnish an affidavit stating that he forbids me to make this deposition on the grounds of further adverse effects to my health and intensification of my illness.”14

Hollywood attorney Greg Bautzer, who represented Hughes on movie matters and TWA, was often seen in the company of Hollywood actresses, in this case Joan Crawford. United Press International

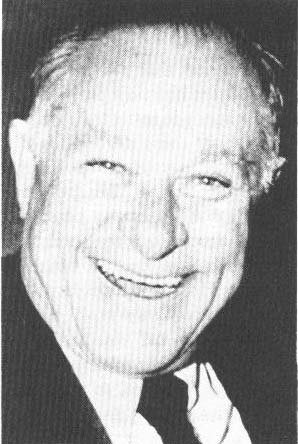

New York attorney Chester C. Davis resigned from a prestigious Wall Street law firm at the start of the TWA v. Hughes lawsuit to form his own firm representing Hughes. United Press International

Bautzer and Davis pursued independent strategies. Bautzer was optimistic that a settlement could be negotiated. Davis was concerned that TWA, believing it had Hughes on the ropes, would insist on overly harsh terms. As a precaution, in the event the lawsuit went forward, Davis advised Hughes to retain a prestigious New York law firm immediately. Hughes could not bear to discuss the possibility. “The lawsuit weighs [so] heavily in my considerations,” he told Davis on July 16, “that I have decided to submit to settlement terms so heavily favorable to TWA that I feel the directors will be afraid to reject such a settlement for fear of the creation of a very serious liability on [their] part in favor of the TWA minority stockholders.”15

Worried that Davis was not pushing hard enough for a settlement, Hughes sent him on a purposeless three-day trip to Houston and gave Bautzer full authority to settle the case in Davis’s absence. “I want no divided responsibility about these negotiations,” he told Bautzer. “I am placing the matter completely in your hands, Greg, with the simple request that you make the best deal you can.”16 Hughes told Bill Gay to keep Davis in Houston for three days. “I don’t want any possibility of his leaving there. Do whatever is necessary to accomplish the result.”17

Davis was kept in Houston for the required three days, but he saw through Hughes’s transparent ploy by the end, and when he returned to New York on July 21, he sent Hughes an angry message. “It would have been preferable if you had told me directly and frankly what you wanted to do, even if you anticipated I would express disagreement at the strategy. I have no objection to your efforts at a settlement through Bautzer. However, I thoroughly disagree with the strategy you are currently following. I want no part in it or in its result, whatever it may be. I do not believe that you are following a course designed to achieve your objectives. I believe that you are hampering a settlement so long as you are not prepared to fight them.”18 Davis ended by bluntly offering to leave the case, on any terms Hughes decided. “There will be no disagreement as to proper compensation for my time.”19

Hughes panicked and, as so often happened when one of his devious maneuvers backfired, he blamed Gay. “Tell Bill this breach with Davis is very likely to cost Bill his job,” he fumed to Paul Winn, an aide then taking dictation at Rancho Santa Fe.20 To smooth ruffled feathers, Hughes instructed Gay to telephone Davis and explain that there had been a communications breakdown, not a strategy change. Gay was to say that he had kept Davis in Houston in the belief that Hughes was planning to call Davis at any moment, but that, unfortunately Hughes’s illness had taken a turn for the worse and prevented him from making the call. Davis accepted the olive branch.

Meanwhile, Bautzer was working day and night to negotiate a settlement. By late July, a tentative agreement had been roughed out. If TWA would drop the lawsuit, Hughes would agree to honor the voting trust for its full ten years and to invest $150 million in the airline over the next two years. In turn, the airline agreed to acquire thirteen more Convair jets that Hughes had previously ordered for TWA, a move that would relieve him of a major financial obligation. TWA insisted that Hughes sign the agreement first, a requirement Hughes considered “unwarranted, unjustified, and an insult.”21 Nevertheless, he signed the papers on July 27 and sent them to Bautzer with orders to hold them until several minor changes had been made. To Bautzer, only a few formalities remained before the crisis would be resolved.

But not all of Hughes’s attorneys were so eager for him to settle. As soon as he read a copy of the agreement, Chester Davis dictated a memorandum to Rancho Santa Fe on July 28, 1961, urging Hughes to think twice before submitting to TWA’s terms. Davis objected in particular to a section which he said amounted to a consent decree. “Irrespective of the legal niceties involved,” he said,

it is common knowledge that a consent decree in any trust action means that the defendant recognizes or admits a course of conduct in violation of the antitrust laws without admitting the particulars constituting the alleged violation…. The inevitable implication is that the Tool Company must have done something illegal even though there is no admission by the Tool Company or any adjudication by the court as to the particulars which could be a violation of the Federal statutes involved.22

Hughes sounded out Robert Campbell, of Andrews, Kurth in Houston, the longtime attorneys of the oil-tool division, and Seymour Mintz of Hogan & Hartson in Washington, the medical institute’s lawyers. Both sided with Davis.

Although he was desperately anxious to settle, Hughes found Davis’s argument disquieting. As the August 8 date for unsealing the complaint approached, he decided “to fight the TWA lawsuit to the hilt.”23 On August 6, he told Gay to line up an influential New York law firm to assist Davis, but to make sure that Bautzer did not know of his activities. “Bill, I want you to roll up your sleeves and put everything else out of your mind,” Hughes told him. “This is far and away the most important assignment you have ever received and please really give it everything you have got. This is going to be an all-out bitter battle and the ramifications of this thing will reach into many, many phases of our operation. These people will be prying around like ferrets looking for something they can use to blackmail us.”24

Always aware of his public image, Hughes asked Gay to telephone William Randolph Hearst, Jr., and ask him to “issue a general directive” to all Hearst editors “that the Hearst papers are going to be on my side in this controversy. Tell Mr. Hearst I would not make this request at this time except this is of such devastating importance I truly need and must call upon everyone who is willing to stand up and be counted as my friend. These people are going to try their best to destroy me in any way they can.”25 In return, Hughes promised he would provide Hearst with exclusive stories about the TWA controversy, much as he had done in 1947 prior to the Senate hearings. “Tell Mr. Hearst they will be hot enough to curl the paper because I have some information and I am prepared to make some statements which will really shake up some of the better known figures of Wall Street.”26

The battle lines drawn, TWA’s complaint against Howard Hughes was made public on the morning of August 8 in Manhattan, and the lawsuit, destined to be one of the most lengthy and celebrated civil cases of the century, went forward.

Now that the battle was on, Hughes’s old combative instincts returned. He and his lawyers were confident. To their way of thinking, TWA had chosen shaky ground in antitrust law on which to make a stand. They believed that although airlines are private corporations, they also serve the public interest and were therefore immunized from the full force of antitrust law by the Civil Aeronautics Board. Until December of 1960, when Hughes lost control, the CAB had regularly approved his dealings with TWA as in the public interest. Hughes’s lawyers reasoned that the federal courts lacked jurisdiction to hear the charges.

Following this logic a step farther, the CAB obviously loomed as crucial to Hughes’s fight to turn back the lawsuit and to recapture his airline. He would need the CAB’s cooperation. Unfortunately for him, Hughes’s standing with the CAB had never been lower. The agency had not forgotten how Hughes had nearly ruined TWA. Even so, shortly after the collapse of the settlement talks late in the summer of 1961, Hughes saw a way to recoup some lost prestige in Washington and at the same time outmaneuver his foes and get back into the airline business. The opportunity came by the oddest of routes.

By the summer of 1961, Northeast Airlines, a small regional carrier based in New England, was verging on collapse. Northeast was controlled by the Atlas Corporation, the investment company still headed by Floyd Odium, the buoyant financier from whom Hughes had bought RKO back in 1948. Later, through a series of complicated stock deals in the mid-1950s, Hughes acquired 11 percent of Atlas’s stock, and thus he owned a piece of the corporation controlling Northeast. Since it is against public policy for a person to control more than one airline, the CAB had forced Hughes to place his Atlas stock in trust.

Hughes was well aware of Northeast’s financial distress. A year earlier he had arranged a $9.5-million loan for Northeast in return for its promise to seek a merger with TWA. Nothing came of the proposed merger, and Northeast’s financial condition deteriorated. By September of 1961, the airline barely had enough “cash on hand to cover one day’s current operating expenditures.”27 Its collapse appeared imminent. The CAB abhors airline failures; they are bad for patrons who are inconvenienced, bad for politicians who hear complaints from outraged constituents, and bad for the CAB itself, which is supposed to prevent such calamities. But how could Northeast be saved? Only through the infusion of millions of dollars in cash. And who would invest such millions in an airline heavily burdened with debt and saddled with an undesirable route structure?

Who other than Howard Hughes? Atlas appealed to Hughes for financial assistance. Early in September Hughes agreed to supply it, but only if the CAB approved. Atlas and Hughes Tool began negotiating a secret memorandum of understanding aimed at providing Northeast with immediate cash and at giving Hughes an option to acquire Atlas’s controlling interest in the airline. If the CAB approved, Hughes would lend Northeast $5 million. To help pave the way at the CAB, Hughes rehired Raymond Cook, the Houston lawyer he had fired the year before.* With close ties to the CAB, Cook would be invaluable in the months ahead.

Hughes now had the CAB where he wanted it. If the agency rejected his offer to bail out Northeast, the airline would almost certainly fail. If it approved the loan, the CAB would be handing yet another airline to a man with a demonstrated inability to run one. On September 12, 1961, representatives of Hughes, Atlas, and Northeast assembled at the CAB’s headquarters in Washington for a special meeting of the agency’s board. The subject was Northeast, and Raymond Cook and Chester Davis made it plain that they expected the board to give Hughes special treatment.

“May I make the observation that quite clearly unusual procedures are required here,” Cook told the four CAB board members who were present that afternoon.28 Davis was more direct: “Let me be very frank. I know for a fact from past experience those who desired to achieve a particular result have always [sought to] examine Mr. Hughes personally. If we are going to get ourselves involved in a hearing where that is likely to develop, I think the conclusion that we would reach is that we are just wasting our time.”29

Jack Rosenthal, a CAB staff attorney, replied. “In effect, you want a guarantee from the board” that Hughes would not be called as a witness.30

“I am not asking for a guarantee of any kind,” Davis answered. “I am merely saying that before the Tool Company will once again, and I repeat once more, come to the rescue of an airline in trouble, we want to be satisfied and I don’t expect [anyone] to do anything for us they shouldn’t do, but we want to be satisfied [that] life [will not be made] more miserable for us than it had already been.”31

“I think you have made your point,” said Robert T. Murphy, vice-chairman of the board.32

After listening to the pleas of Hughes’s lawyers and representatives of Atlas and Northeast, the CAB adjourned, deciding only that Hughes, like anyone else, would have to file a formal application before it could act. Still, Hughes was optimistic that the CAB would ultimately have no choice but to go along with his masterplan.

In October, when Northeast’s cash ran so low that it could not pay its bills, Hughes quietly agreed to guarantee its fuel bills and keep the planes flying. On October 31, 1961, Hughes and Atlas filed a formal request with the CAB seeking permission for Hughes to supply funds to the ailing airline. Disclosing publicly that Hughes had been guaranteeing the airline’s fuel bills for two weeks, the application provoked a row. Eastern Airlines, Northeast’s competitor on the Florida run, called for the “criminal prosecution of Howard Hughes” for having “illegally acquired control.”33 On November 9, the CAB issued an interim order that was a vague slap at Hughes’s dealings. Calling on him and Northeast to file a complete report of all agreements between them, the CAB said it appeared that Hughes Tool had enough power over Northeast to control it.34 Such control was, of course, illegal without CAB approval. Hughes countered two days later by withdrawing Northeast’s fuel guarantee. Five days after that, Northeast made a frantic plea to the CAB to modify the interim order questioning the legality of Hughes’s aid lest the airline collapse. Hughes had immensely increased the pressure on the CAB to act in his favor. It was now only a matter of time, he felt, before the CAB would come around.

THE GERM WAR

Hughes directed the TWA and Northeast strategies from his bedroom. His mental condition had deteriorated and his seclusion had deepened at Rancho Santa Fe, where he now rarely left his bed. Hughes summoned aides to the room day and night, where they would kneel beside the bed as Hughes, often with Jean sleeping next to him, dictated memoranda that ran from a few sentences long to several thousand words. The memoranda then were sent to Operations by teletype from the cabana next to the swimming pool. Hughes’s compulsive need to send messages at all hours did not disturb his wife nearly so much as his nervous habit of clicking his long toenails while he dictated. To muffle the sound, Jean put Kleenex between her husband’s toes.35

Next to TWA, the most consuming issue Hughes dealt with in the summer of 1961 was a project to “isolate” five Electras at the Lockheed plant in Burbank. Hughes wanted to purchase three of the planes—apparently for his personal collection—but until he decided which three to buy he wanted all five so well guarded as to be isolated from germs. Two of the planes were parked outside and Hughes worried that the sun, beating down on the fuselages, would make them incubators for microorganisms. He asked Jack Price, a Romaine Street operative, to work out a way to air-condition the planes. Price came up with several ideas—one of which was to purchase window air conditioners, anchor them on stands outside the Electras’ cabin doors, and feed cool air inside—before Hughes decided to tow the planes inside a hangar. To preclude the possibility of an aircraft worker’s coming in contact with one of the Electras, and thereby spreading germs from human to airplane, Hughes gave Price a detailed memorandum on how to accomplish the move.

Explaining that the project was more important to him “than any you have undertaken before,” Hughes beseeched Price to do “an even finer job of moving than you have ever accomplished before.”36 Hughes wanted the planes towed with a precision that surpassed all past efforts:

All I can say is to ask you as urgently and as humbly as I know how—I ask you and implore you, Jack, not to be satisfied with doing it as well or as perfectly or as smoothly or as gently as you have in the past, but please tonight just simply bust a gut striving as you never tried to do anything before in your life not merely to equal the best operation you have achieved in the past, but instead improve upon it and tonight conduct the most careful, the slowest, most perfect, most gentle, the smoothest towing operation ever, ever conducted before and with each acceleration and deceleration so infinitely gradual that it would take a microscope to measure it.37

A few days after the Lockheeds were finally moved, Hughes faced an even graver germ crisis. On September 3, 1961, Robert Gross, the chairman of Lockheed and a business associate of Hughes, died of cancer. Gross’s wife invited Hughes to a private funeral and asked him to be an honorary pallbearer. Unable to leave Rancho Santa Fe, Hughes, of course, declined. He asked Gay to send a message to Mrs. Gross graciously thanking her for the invitation and explaining that he was unable to attend because of illness. As a sign of friendship for Gross, Hughes instructed Romaine Street to send flowers, telegrams, and messages of condolence to the family, to “really go the limit on this.”38

Once the formality of sympathetic expressions was in motion, Hughes ordered Romaine Street to put into effect the most far-reaching germ-fighting program ever implemented to make certain that germs from the late Robert Gross did not somehow wend their way to Rancho Santa Fe. As a rule, Hughes feared all germs equally. The one exception, a kind of superbug, was the hepatitis microbe. He had become so terror-stricken of hepatitis that he saw it everywhere, and now for some reason he was convinced that Gross had died of hepatitis, not of cancer. (Ironically, at different times over the years Hughes stood a greater chance of succumbing to hepatitis in his own filthy surroundings, but such was the severity of his disorder that he never recognized this.) Hughes directed Romaine Street to seal off every person and business involved with Gross, his widow, or his funeral, from all contact with the Hughes empire to prevent the “backflow” of germs:

Everything involved in this entire Gross operation, whether it be flowers, telegram, no matter what the hell it is, I want the absolute maximum greatest precaution and even greater precaution than we have ever taken before to close off all return paths. In other words to make the operation truly, literally, absolutely irreversible. This will mean if we are going to use our florist for the flowers then the delivery will again have to be made by some messenger service whom we will never use again, who will not be sending us literature, a bill, who will not be writing to us or sending or mailing us any thing, who will not be calling upon us to try and solicit business, and furthermore, who will not do anything like this with our florist, for soliciting of business, sending literature to our florist, not sending bills or invoices to our florist, and not be used again by our florist in any way. And again I say, the messenger is not to be in a position to attempt to solicit business further from our florist or from us. The message can simply go by telegram. Also I want an absolute blockade for the time being against any pick up at the Lockheed plant. Don’t be sending anybody to pick up engineering data, flight manuals from Jack Real concerning Jet Stars, Electras, or anything else. I would like to block off incoming correspondence, data, packages, any incoming items, large or small, even a slip of paper from the Lockheed factory as well as from Gross’s office.

Mrs. Gross will undoubtedly write a message of thanks for the flowers and Bill can send me a very complete memo setting forth the scheme for the receipt of this message and Bill Gay can let me know how this will be accomplished. We will have probably 48 hours before we have to worry about that one, but the message telling me how that is to be done will have to be telephoned to Paul [Winn] and I don’t want anybody else to know about that.

I want the necessary instructions given to achieve a block off of all return avenues and to make the situation concerning the flowers and the telegram and anything else of that nature which may be required—to make any such transmission completely irreversible so there is absolutely not the slightest possibility of any back flow or return transmission or anything of that kind even of the most indirect nature such as I have described herein.”39

Now that Hughes and Jean were living in the same house, his phobias sometimes upset even her. Always fearful of dust, he refused to let her clean their bedroom. Jean tried to comply. She kept the rest of the house spotless and ignored their room. As time went by and the film of dust grew into mounds of dirt, she decided to clean—with or without Hughes’s blessing. When Holmes, the aide on duty, heard about it, he volunteered to run the vacuum cleaner, but Jean insisted that she wanted to do it herself.

Placing the humming vacuum-cleaner cannister outside the bedroom one night, Jean poked into the room with a long extension hose and began to massage the heavy shag rug that covered the floor. Hughes looked on in silence from his bed as Jean ventured farther into the room, followed by Holmes, who carried a flashlight, shining it into the dark corners that Jean was trying to reach with the nozzle. As they neared Hughes’s bed, he said, “Don’t touch the TV set,” which was covered with dust. Otherwise, he did not interfere. Jean stuck the nozzle under Hughes’s bed and began running it back and forth. The task of picking up the dust underneath, however, proved impossible without moving the bed, and eventually Jean, as Holmes remembered, “ran out of steam” and gave up.40

Hughes was not insensitive to Jean’s own emotional crises. One day her cat wandered away and failed to come home. Jean was distraught. When the aides failed to find the missing animal, and Romaine Street, and in particular Bill Gay, did not respond to the crisis, Hughes became furious. In a heated telephone conversation with Kay Glenn, Gay’s assistant, Hughes both spelled out alternative strategies for finding the cat and vented his anger at Gay. He told Glenn:

I want somebody who is an expert in the ways of animals of this type and who would know where to look and how to look and how to go about this line. I mean, for example, directly, dogs get a cat treed up a tree and the cat just stays there, afraid to come down, and the dogs rush around in the vicinity somewhere…. If we can find some evidence… the cat’s body, or somebody who heard the episode…. Now, it just seems to me that if Bill gave a goddamn in hell about my predicament down here he would have obtained from somewhere, from some place—I don’t know where from—from Los Angeles or some place, he would have got some expert in the ways of animals, cats in particular, and had him come down here and then put about eight or ten of Maheu’s men at his disposal and they would have conducted an intelligent search based upon being instructed by somebody who knows the habits and ways of an animal of this kind. But, instead of that, so far as I have been able to make out, not one thing has been done….

Kay, I am not going to run this organization this way any more and now Bill Gay goes cruising around today, having a good time, where nothing is done about looking for this cat down here. Not one goddamned thing except having a few of our guards cruise around in their cars. Maheu is in Los Angeles. You could have had him send a team of men down here. You could have got some experts who knew about cats and know where to look. There are many, many things that could have been done during the entire period of today to try and locate this animal or find out what happened to it today. I am goddamned sure that if some police case depended upon the determination of knowledge of what happened to this animal today, by God, in Heaven, they would have had a team of men scouring the countryside and located the cat or some shred of evidence of what happened to it.

This is not the jungle; this is not the Everglades; this is not New York City with the dense population. It is thinly populated and it is no problem at all to question all the people here and have them questioned by somebody and get at the truth and not permit somebody to conceal the truth just because they are afraid of being sued or something like that. Proper questions by people skilled in questioning could have been had. The animal could have been searched for by a team of people skilled in the ways of animals of this type. I know one thing; if a zoo had lost some valuable animal in this area, there would have been twenty-five or thirty men scouring the countryside, men skilled in the habits and ways of an animal of this kind and would have found it by now.

If there was a dangerous animal escaped from some zoo or circus like a goddamned wildcat or leopard or some animal, you can be goddamned sure they would have found it by now. I consider the loss of this particular animal and the consequences it has had to my wife to be just as important, and in the light of my resources and ability to pursue a matter of this kind, I feel that it is absolutely no reason why a search should not have been instigated for this animal equal in any way to what would have happened if some damn train had broken down here and some leopard or panther or whatnot had escaped. There is absolutely no reason why a man of my resources and having the resources and organization that I have got, there is no goddamned reason in the world why efforts to locate this animal should not have been made equal in every way to what would have occurred if some dangerous animal had escaped in this area….

In this situation here you don’t think Bill has done anything wrong, going off today to pursue his social activities, whatever it may be, while this situation of complete tragedy occurs down here and my home is likely to be broken completely assunder [sic]. You don’t think that at all. You think that is my business and my worry and if Bill wants to go to his social affairs that is OK and I am expecting too much…. You repeat this please, if you took this down in shorthand or on the tape. I wish you would repeat it wholly, the whole thing from A to Z and if it is on the tape, I hope you will play it seven times because I never meant anything more sincerely than I mean this and if this is the end of the road for this group then let’s wash up the other end of Romaine Street just as we did with Dietrich….41

Two days after Hughes’s irate telephone conversation, Jean’s cat padded quietly out of the trees and into the house.

While waiting for the Civil Aeronautics Board to act on his bid to take over Northeast Airlines, Hughes and Jean moved back to Los Angeles, on Thanksgiving Day of 1961. The plumbing at the Rancho Santa Fe house required major repair, and rather than let plumbers into the house, Hughes decided to move.42 Romaine Street had several expensive homes under lease in Beverly Hills and Bel Air. Hughes chose a French Regency-style mansion at 1001 Bel Air Road, in a neighborhood of lavish estates. The new house afforded spectacular vistas in all directions—the Santa Monica Mountains to the north and west, the vast Los Angeles basin with its myriad cities and towns to the east, and the gentle coastal ranges rolling out like waves to the Pacific Ocean to the south. But most appealing to Hughes, the house provided extraordinary privacy. A dense growth of foliage and trees shielded all but the very top of the roof from Bel Air Road; a heavy iron—and patrolled—fence barred access to the grounds.

At Bel Air, Hughes and Jean gave up on their brief experiment at cohabitation and moved into separate quarters. Hughes chose a spacious, thickly carpeted bedroom with its own bathroom and dressing room at the southeast corner of the house, far away from the living and dining areas. There was a large window looking south onto far-off hillside estates and beyond them to the mountains bordering the sea. But, as at Rancho Santa Fe, Hughes was oblivious to the beauty around him. Craving only seclusion, he had thick drapes installed to block out the view and shield the room from sunlight. Only the barest essentials surrounded him—a double bed, a small side table, a table-model television set, a contour chair, and two overstuffed chairs. Romaine Street workmen installed a window air conditioner designed to control and purify the air at all times. On arrival, Hughes climbed promptly into bed, as though he had transferred from one hospital to another.

While Hughes cared little where he was living, Holmes and Crawford were glad to be back in Los Angeles. It brought them closer to their families and did away with the weekly two-hundred-mile round trip. Romaine Street sent a third aide to work at Bel Air—George A. Francom, Jr., a quiet, easygoing, devout Mormon and family man. A native of tiny Payson, Utah, the forty-four-year-old Francom had served as a Mormon missionary and attended Brigham Young University before the Second World War. With hopes of becoming a pilot, he enlisted in the air force but “washed out” because of airsickness.43 For the rest of the war he was a medical technician. He later attended the University of Southern California, planning to become a dentist, but dropped out after two years. He was working in heavy construction in 1954 when a friend told him that Hughes Productions was looking for a driver. Like almost everyone else at Romaine Street, Francom had started by chauffeuring starlets and running errands. With Francom’s arrival at Bel Air, the three aides divided up the daily schedule into shifts of eight hours each. They worked every day, seven days a week, covering for each other during emergencies.

Merely having the aides on twenty-four-hour duty at the house was not enough for Hughes. He wanted them in his bedroom. So a small table and two chairs were placed near the door leading to the rest of the house, a telephone was installed for contact with Operations, and the aide on duty sat there for hours at a time, reading or talking to Operations, while Hughes lay propped up in bed at the opposite end of the room. The aides, however, were uncomfortable with the arrangement and soon persuaded Hughes to let them convert a dressing room on the other side of the bathroom into an office. Since it was only a few feet away from the bedroom, the little cubicle was close enough for Hughes’s comfort, yet sufficiently removed to give the aides some privacy. Holmes, a smoker, was particularly pleased with the arrangement. Now when he wanted a cigarette he could step into the big walk-in closet and light up. To allay Hughes’s fears over not being able to see them, the aides bought him a bell and placed it on the table next to his bed.

Less than two weeks after the move to Bel Air, the CAB handed Hughes his first victory in the grand plan to recapture control of TWA. On December 4, 1961, the board ruled that Northeast could seek emergency aid from the Hughes Tool Company: “We find that Northeast is in such a critical financial condition that it is in need of emergency financial assistance; without such assistance, it is very likely that the carrier will be forced into bankruptcy; and that such a financial collapse will have serious adverse effects on the public interest.”44 For the time being, the CAB sidestepped the delicate questions of whether Hughes had already gained control and whether his return to the airline business was in the public interest. The board promised to make a full inquiry into those questions in the future. “All we decide,” it said, “is that the advancement of funds is not adverse to the public interest and meets the approval of the board.”45 Although hardly a warm reception from the CAB, the ruling was nevertheless a victory for Hughes and he gladly accepted it.

Now Hughes moved swiftly to wind up the Northeast deal. He dispatched Raymond Cook to New York to negotiate an agreement with the Atlas Corporation to buy its 55-percent interest. Hughes outlined two proposals. The first was “$3,5000,000 cash for Atlas’ interest in Northeast—no strings, no conditions, no option.” The appeal of this offer, Hughes said, would be that he was rescuing one of Atlas’s major assets from bankruptcy. “I think the absolute, all-out, horror-filled tragedy of Atlas permitting Northeast to go bankrupt to the serious financial destruction of the stockholders is something so serious that it would destroy public confidence in Atlas as a sound investment trust.”46

His second proposal was the “exchange of my [Atlas] stock plus $1,000,000 cash for Atlas’s holdings in NE.”47 Hughes had originally paid slightly more than $6 million for his Atlas stock in the 1950s. If Atlas refused to accept that as the value of the holdings today, Hughes contended, it had only itself to blame: “Atlas management had full control of my $6,000,000 plus and if it is not worth $6,000,000 today, the responsibility lies only one place—Atlas—and it is from this same Atlas that we are contemplating buying Northeast, so I think due adjustment is owing us.”48 Whichever proposal was accepted, Hughes agreed to write off the $10.2 million that Hughes Tool had lent Northeast to keep it flying.

His new orders in hand, Cook returned to the bargaining table and wrapped up the negotiations. Hughes ended up paying $5 million instead of $3.5 million for Atlas’s shares in Northeast, and agreed to provide $1 million more to the airline in interim assistance until the CAB approved the sale. With Atlas’s 55 percent plus his own holdings, Hughes would own 66 percent of Northeast Airlines. The transaction was completed on December 28, 1961. Almost a year to the day after the eastern financial establishment had forced him to relinquish control of TWA, Hughes was back in the airline business.*

Buoyed by the outcome of the Northeast move, Hughes struck out at his adversaries less than six weeks later. On February 13, 1962, he filed a countersuit in United States District Court in Manhattan against TWA, Breech, Tillinghast, and the lending institutions that had imposed the voting trust in December of 1960. Charging that the lenders had illegally conspired to seize TWA, Hughes asked the court to dissolve the voting trust, restore him to control of TWA, and award him $366 million in damages. TWA’s case against Hughes was now threatening to sink into a swamp of litigation. It was no longer a matter of TWA v. Hughes. Now there were the Equitable Life Assurance Society, Metropolitan Life, the Irving Trust Company, and Dillon, Read, as well as Breech and Tillinghast. There would be more briefs, more depositions, more interrogatories. The case had already generated work for a small army of lawyers; it could only get worse.

MANHUNT

On the West Coast, Frederick P. Furth, a young lawyer in Sonnett’s firm, was having his own problems. Only three years out of the University of Michigan Law School, Furth had been handed the unenviable assignment of serving Hughes personally with a subpoena. Hughes had not been seen in public for years. He was shielded by a private guard force and an intricate communications network designed specifically to insulate him from the outside world. He had spent years perfecting a reclusive lifestyle. How could any outsider penetrate such a system? Still, TWA was obliged to make the effort, and the energetic Furth set forth.

In Los Angeles, he teamed up with Alfred E. Leckey, a private investigator and former FBI agent. They hired a squad of sleuths to ferret out information on Hughes’s homes or whereabouts. Furth and Leckey tried to serve the subpoena at places they suspected Hughes owned or leased and where he might be living. They were barred from the grounds of Rancho Santa Fe. At the gate of the Bel Air mansion they were turned away by the crewcut guards. They got no closer at other houses from Palm Springs to Hollywood where Hughes was reportedly living. For weeks Furth conducted a vigil at the Beverly Hills Hotel, where Hughes still maintained a bungalow. Hughes, naturally, never appeared.

To help thwart the searchers, Hughes called on Robert Maheu. Using the experience gained in years of counterespionage and corporate intelligence work, Maheu subverted the manhunt. Erroneous tips were passed into the TWA camp that kept Leckey’s private sleuths in perpetual motion. At one time or another Hughes was “spotted” in a New York elevator, a Los Angeles drugstore, and a secluded Mexican resort. The press eagerly followed the hunt. On hearing that Hughes strolled through the rose garden at Bel Air in the early morning hours, Thomas Thompson, a writer for Life, armed with a photographer, camped overnight outside 1001 Bel Air Road hoping for a glimpse.

All—reporters, detectives, and lawyers alike—were unable to find Hughes. The tips on Hughes’s whereabouts, so skillfully planted by Maheu, led nowhere. Frustrated, the TWA investigators staked out the offices and homes of Hughes’s top deputies in Los Angeles, hoping one of them might lead to the man. Leckey himself shadowed Maheu, all to no avail. As time went by, the Hughes-hunters developed a grudging admiration for their quarry’s security system, and a near mysticism toward the man himself. Hughes seemed by some extraordinary means to be moving secretly around Southern California, shuttling among four or five mansions, always just a step or two ahead. An impressed Saturday Evening Post writer called the phantom industrialist a “modern-day Scarlet Pimpernel.”49

Where high-priced Wall Street lawyers, street-wise investigators, and an army of experienced newsmen failed, however, a child succeeded, slipping through the previously invincible security system to come face to face with Howard Hughes in his bedroom at Bel Air—a bedroom that Hughes never left throughout the manhunt. The incident occurred one day when Jean’s sister was visiting the house with her two children. Her son, about five years old, was exploring the long hallway that ran from the living room to Hughes’s bedroom at the east end of the house. The door to that room was always kept closed but rarely latched. Jean had become irritated at the sound of Hughes’s door opening and closing at all hours of the day and night as aides and cooks passed in and out. To solve the problem, the aides affixed layers of friction tape to the edge of the door and the door frame. This served to keep the door shut tightly and at the same time allowed it to be opened and closed without a sound. But on the day when Jean’s nephew started down the hall toward the forbidden room, the system failed. Through constant use the tape had worn down, and although the door was closed, only the slightest nudge was necessary to open it. The little boy, curious to see what was on the other side, grabbed the handle and pushed.

A moment later, Hughes looked up in surprise from his bed to see a small boy staring up at him. “Hi,” said the boy. John Holmes, who was then on duty, dashed into the room, picked the boy up, and started to whisk him out.50 The startled Hughes asked who the boy was.

“That’s E.J.,” Holmes answered, adding that the child was Hughes’s nephew.51 The boy went by his initials, and Holmes did not know his full name. Holmes was starting out of the room when he met Jean coming down the hall, a big smile on her face. She took her nephew in her arms and carried him back into Hughes’s bedroom, where she introduced them. She was amused by the incident and laughed as she took E.J. back with her to another part of the house.

Hughes did not think it was funny.

“Well, how did he get in here?” he asked Holmes when they were alone.52

Holmes made a quick examination and explained to Hughes that the boy had been able to simply push the door open. Hughes was skeptical. He thought Holmes had slipped up and left it open, allowing the first uninvited stranger in years inside to see him. He wanted a full report and Holmes obediently prepared one, closing with the fact that fresh tape had been applied to the door and frame and that the bedroom was once again secure.53

The more time they spent with Hughes, the more adept the aides became in recognizing his moods. As George Francom put it, “We didn’t disturb him with a lot of things which normally a normal person would have liked to know about.”54 They had also perfected their sympathetic responses to Hughes’s bizarre demands, handling with equal facility his simultaneous wars on germs and on Wall Street. Romaine Street had sent in another Mormon to ease the staff workload, bringing to four the number of attendants who looked after Hughes’s every need around the clock. The extra man was needed because Hughes’s withdrawal was continuing. Not only had he shut off all personal contact with his lawyers, the tool company executives, and all other outsiders, but now he used the telephone less and less, relying more on the aides to act as both voice and ears to the world at large. Messages to and from Operations and Hughes executives were transmitted through the aides. The latest addition to the staff was Levar Beebe Myler. Like many of the other Mormons in the organization, the forty-year-old Myler had been born and raised in Utah. After working as an air force mechanic during the Second World War, he took several odd jobs in the West, and entered first Los Angeles City College and then Idaho State College with the intention of becoming a mathematics teacher. In 1950, after one year of college, Myler returned to Los Angeles. When he learned of a job opening at Romaine Street through the Mormon church’s employment office, he applied and was hired as a driver. For the first few years, he chauffeured actresses, delivered RKO films, ran other errands, and did “whatever needed to be done.”55 In the late 1950s, he was appointed to the “President’s staff,” the designation Bill Gay had given to the cadre of helpers who were assigned to Hughes personally.

And for the first time now, the asylum had its own one-man “medical staff”—Dr. Norman F. Crane, a Beverly Hills internist who had once shared offices with Dr. Verne Mason, the physician who treated Hughes following his 1946 plane crash and went on to head the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Crane’s duties were quite unlike those of most doctors. He did not treat Hughes for his mental disorders. He did not give him thorough physical examinations. He did not treat him for any serious physical ailments. Rather, Crane’s practice was limited largely to supplying the prescriptions for Hughes’s drugs.56 In the beginning it was Dr. Mason who furnished the prescriptions, but that responsibility had been taken over gradually by Crane.

During Crane’s periodic visits to Bel Air, two changes occurred in Hughes’s drug habit. For more than fifteen years he had been taking Empirin Compounds, including one containing codeine. And for more than a decade he had been taking, orally, one-grain codeine tablets. Now Hughes was provided with one-grain codeine tablets that could be dissolved in water and injected by syringe. In addition, he was given Valium, a nonnarcotic, but habit-forming tranquilizer. The prescriptions were written in the names of the aides—especially Holmes, Crawford, and Francom—and filled at designated pharmacies. The Horton & Converse drugstore on Wilshire Boulevard, where Crawford began filling prescriptions in the 1950s, remained a favorite.57 Another was the Roxbury Pharmacy on Olympic Boulevard in Beverly Hills.58

Hughes himself had fallen into a fixed routine. He usually slept until midafternoon, waking at two or three o’clock and receiving a glass of fruit juice for breakfast. His reading had picked back up, and he read then or watched an afternoon movie on television. If he decided to read, it was a weekly newsmagazine, Time or Newsweek, a recent newspaper, or more often, bulky manuals of aircraft specifications. Using a powerful, black-handled magnifying glass, he scanned the columns of type and specifications like a detective in search of a clue. He was farsighted and very much needed eyeglasses, but he refused to wear them, or even submit to an eye examination. In the early evening he watched the news and then studied TV Guide, selecting a series of television shows and late movies to watch until dawn. He rarely screened movies at Bel Air. Los Angeles television stations were serving up a steady diet of the films he liked—adventure movies with a lot of action and little romance. When the last movie ended, Hughes ate his one meal of the day, usually a steak and a vegetable, topped off with his favorite dessert, French vanilla ice cream. He ate slowly, sometimes taking as long as two and a half hours to finish a meal. Then he turned to business, reading memoranda from the field and dictating replies. In the early-morning hours, when many Americans were arriving at work, he dropped off to sleep.

Except for visits to the bathroom, Hughes remained in his double bed, which he later exchanged for a metal hospital bed he ordered specially. He seldom washed. His hair fell down his back. His beard trailed onto his chest. And he was naked most of the time. His sealed chamber was barred to all but a few authorized people: the aides, the cooks, his doctors, a few trusted functionaries from Romaine Street like Oran Deal—who dutifully picked up and disposed of Hughes’s trash each day—and Jean Peters. Jean usually visited twice a day, once in the late afternoon and again for twenty or thirty minutes late at night. Her visits were arranged through the aide on duty. Hughes did not like to be interrupted during a television show or while occupied in one of his rituals. When ready to see his wife, he summoned the aide: “Would you ask Mrs. Hughes if she could visit now?”59 Jean would make her way from the other side of the house, draw one of the overstuffed chairs up close to his bed, and tell him about her day and her plans for the next. Hughes would respond by telling her about his day. To win her sympathy, he often complained of a “very bad day, didn’t eat as much as he wanted to, didn’t feel good.”60 If Jean had enjoyed a good day, the aides recalled, then Hughes invariably reported the opposite.

The secrecy that cloaked Hughes’s life was so complete that no word leaked out indicating the true state of the marriage. What little did appear in print suggested that the two were—in their own eccentric way—happily married. A September 1962 article in Life said that “according to one of the few friends who still see Jean Hughes, life with Howard is a ‘lonely one,’ but she has apparently adjusted to it. She genuinely loves Howard, and despite his strange ways, theirs is a good marriage.”61

THE VICTOR AND THE SPOILS

Despite the failure of the TWA manhunt, John Sonnett, the architect of TWA’s case, was determined to keep the pressure on Howard Hughes. By ducking the subpoena, Hughes had both complicated and delayed TWA’s case and convinced Sonnett of the wisdom of his course. Clearly, Hughes was deeply afraid of being forced into the open. In the spring of 1962, Sonnett hit on a new avenue of attack.

If TWA could not find Hughes, perhaps the tool company could be forced to disclose his whereabouts. Sonnett drew up interrogatories—a series of formal written questions requiring written answers under oath—focusing on Hughes’s residency and applied to the court for an order compelling the tool company to respond. Judge Charles M. Metzner had appointed a special master, J. Lee Rankin, former solicitor-general of the United States under Eisenhower, to represent him at pretrial proceedings and depositions, and it was to Rankin that Sonnett appealed. If Rankin approved, Hughes’s wholly owned company would have to reply or risk a contempt citation. Sonnett’s timing could not have been better. By avoiding the subpoena, Hughes had impressed the court as one who held himself above the law. While TWA executives were submitting to months of questioning by Hughes’s attorneys, Hughes was beyond the reach of his opponents. On April 17, 1962, Rankin granted Sonnett’s motion and gave TWA the right to question the tool company about Hughes’s whereabouts. July 1 was the deadline for a reply.

The next day, April 18, Sonnett filed a second TWA lawsuit against Hughes and the tool company, this one a $35-million damage claim in the New Castle County Chancery Court in Wilmington, Delaware, the state where both the tool company and TWA were incorporated. In going to Wilmington, Sonnett sought to apply pressure on Hughes by taking advantage of an unusual provision in Delaware law. In Delaware civil cases, the stock of a defendant can be seized and sequestered by the court while the lawsuit is being heard. Thus, if Hughes failed to appear, the court could order his stock sold to satisfy any judgment. The day the complaint was filed, TWA obtained an order seizing Hughes’s 25,000 shares of Hughes Tool Company stock. The stock could not be voted or sold without approval of the court. For the first time, Hughes’s ultrasecret corporate umbrella was technically under the control of an outsider.

Of TWA’s two legal maneuvers, the court order requiring the tool company to divulge Hughes’s location posed the gravest immediate threat to Hughes. Unlike the manhunt, which could be foiled, the residency questions had to be answered or Hughes would run the risk of inviting a default judgment. As he would so often, Chester Davis appealed to the special master for an extension, and when that was denied, appealed once again to Judge Metzner for more time. On July 27, the judge extended the tool company’s deadline until August 27.

Hughes was running out of time. Would he answer? When August 27 came and went, Sonnett thought not. But the next day, Davis surprised him. He had in his possession, Davis said, a letter from Hughes authorizing acceptance of the long-delayed subpoena calling for Hughes’s appearance for a deposition. Rather than respond to the court order to disclose Hughes’s residence, Davis had chosen a lesser evil, and one that would buy him more time. Davis asked that the document not be made part of the court record. Sonnett was intrigued. A few days later, when he got a look at it, Sonnett was puzzled by Hughes’s so-called authorization. On a standard eight-by-eleven sheet of white paper, bearing no letterhead or any other identifying mark, was a simple declaration: “Mr. Chester C. Davis. You are hereby authorized to accept service on my behalf.” The paper was signed: “Howard R. Hughes.”62 There was no date, no address, no mention of the case, nothing at all to bear out the authenticity of the document.

On September 6, 1962, Sonnett rocked Judge Metzner’s courtroom in Foley Square by charging that the Hughes authorization was a fraud. Sonnett had called in Charles A. Appel, Jr., a handwriting expert, who concluded that the signature on the paper was not Hughes’s. Sonnett told the judge: “It is beyond doubt that somebody in the Hughes Tool Company willfully, knowingly, purposefully, in order to mislead counsel for TWA and this court, submitted a forged document. I think on that ground alone your Honor should strike the answer and give us a default judgment.”63 Although Sonnett did not know it, Hughes’s signature had been forged by a Romaine Street lieutenant. Whether it was the first time his signature had been forged, is uncertain, but it would not be the last. Still, Judge Metzner was in no hurry. Earlier that morning, he had learned that the subpoena calling for Hughes’s court appearance had finally been served. Davis had accepted it for his client in Los Angeles. “If Mr. Hughes appears on September 24th,” the judge asked, “then hasn’t all of this been moot?”64 He took no action on TWA’s forgery charges. The stage was set for Hughes’s deposition.

It is unclear whether Davis was aware of Hughes’s mental state and that he was totally incapable of appearing in a courtroom. Davis had never met Hughes, had only talked to him a few times on the telephone. Whatever the case, Davis initiated a series of evasive actions and counterattacks to keep Hughes out of court. By deluging the court with motions, he won two postponements. But on October 29, Rankin, the special master, set a mid-February appearance date and warned that there would be no more extensions.

Davis then appealed to the United States Court of Appeals, claiming, as he had all along, that the CAB, not a federal court, was the proper forum to hear antitrust charges. The motion was denied. Ten days later, Davis hurriedly filed a similar motion before Judge Metzner. This was also denied. Time was running out again. Hughes was to appear at 10 A.M. on February 11, 1963, in the United States Courthouse in Los Angeles to give his testimony. In deference to his hearing problem, special amplifying equipment and a set of foamrubber padded earphones were provided in the courtroom. To almost no one’s surprise on February 11, Hughes did not appear.

Sonnett had been been right. Now he moved swiftly in New York for a default judgment. It seemed certain that the lawsuit would never even advance to a hearing on its merits. By defaulting, Hughes had given TWA a victory without a contest.

On May 3, 1963, Judge Metzner awarded a default judgment to TWA and dismissed Hughes’s $366-million countersuit. Contending that Hughes’s deposition was essential to the case, the judge said his failure to appear was “deliberate and willful and justifies the court entering a default judgment.”65 Metzner referred the case back to the special master to establish the amount of the damages, which TWA said could run as high as $145 million. The only ray of hope for Hughes in the otherwise crushing defeat was Judge Metzner’s inaction on TWA’s motion for a court order forcing Hughes to sell his 78-percent stock interest in TWA: “The propriety of granting this prayer for relief will be determined [later] by the court.”66 Chester Davis took the only option he had—he appealed the decision to the United States Court of Appeals.

Admirers and critics of Howard Hughes might disagree in their evaluations of his intelligence and business acumen, but on one point there is no argument. He was exceptionally strong-willed and stubborn. Once he engaged in a fight, he stayed to the end, and so it was in the TWA struggle. In the spring of 1964, as he awaited the decision of the Court of Appeals, Hughes launched a legal counterattack against TWA.

On April 29, 1964, Hughes Tool applied to the CAB for permission to acquire $92.8 million in notes outstanding from the loan agreements executed at the time the voting trust was imposed. It was a bold stroke. If the CAB approved, Hughes could buy out the lenders, dissolve the voting trust, and regain control of TWA. The securities were 6.5-percent sinking-fund notes held by the Equitable Life Assurance Society and the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. In addition to serving notice on TWA that the battle still raged, this latest move also proved that Hughes, close to bankruptcy in 1960, had weathered the storm. The tool company was once again producing profits to underwrite the rest of his empire.

But before the CAB could act, the United States Court of Appeals on June 2 affirmed Judge Metzner’s default judgement and, if anything, came down even harder on Hughes for his “intolerable” conduct in the case.67 The three-judge panel ruled that Hughes’s “deposition was absolutely essential to the proper conduct of the litigation. Yet he and [the tool company] seized upon every opportunity to forestall this event. Hughes and [the tool company] seemed to look upon the entire discovery proceedings as some sort of a game, rather than as a means of securing the just and expeditious settlement of the important matters in dispute.”68 Last, the court dismissed Hughes’s claim that his conduct at TWA had been “immunized” from antitrust law by the CAB, ruling that the CAB’s approval of his control of TWA “did not carry with it approval of every transaction which [the tool company] might choose to effect in the exercise of its control.”69 Hughes had lost the second round. Davis began preparing an appeal to the United States Supreme Court.

Five weeks later, the CAB handed Hughes a stunning, if temporary, victory. Acting on his April 29 application with extraordinary speed, the board voted to allow Hughes Tool Company to reassume control of TWA by acquiring the $92.8 million in notes from Equitable and Metropolitan. The board’s only condition was that Hughes would first have to offer a plan divesting himself of control in Northeast Airlines, since one person could not control two airlines. The CAB order was Hughes’s greatest coup. That the decision was made without a full-scale CAB investigation, and despite the pending TWA lawsuit, and in violation of the CAB’s own 1960 dictum that said Hughes would not be permitted to run TWA ever again without a “searching inquiry” by the agency, was a measure of Hughes’s restored political influence at the CAB. TWA was enraged. Tillinghast found the CAB order “deeply disturbing.”70 In view of the lawsuit, he was “astonished” that the agency could issue an order “without any hearing.”71 TWA appealed.

The CAB maneuver was brilliant, but in the end not enough to reverse the tide of battle. On December 7, 1964, the United States Court of Appeals in New York set aside the CAB order, claiming that the agency had acted improperly. In March of 1965, the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal in TWA v. Hughes, meaning that the judgment against Hughes was left to stand. One by one, the avenues of appeal were sealed off. Now only one remained—appealing to the Supreme Court the decision setting aside the CAB order. But Hughes could not have been hopeful. Rejected consistently by the courts, he was beginning to worry about what the case might eventually cost. After more than four years, his goal of recapturing TWA was even more distant.

In October of 1965, the Supreme Court, confirming Hughes’s worst fears, announced that it would not review the Court of Appeals decision which overturned the CAB order. The battle was virtually over. Still to come were only hearings before the special master to establish the amount of damages he would have to pay TWA. More important, it now seemed impossible for him ever to control TWA again. Faced with that prospect, he decided early in 1966 to sell out.

With airline stocks booming, the timing was perfect. A group of brokerage firms headed by Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith was organized to handle the sale. Documents were forwarded to Romaine Street, which sent them on to Bel Air, where Hughes signed them, authorizing the sale of his TWA shares. On the morning of May 3, 1966, the Hughes era at TWA ended. His 6,584,937 shares were snapped up at $86 a share in little more than an hour. After brokers’ fees, Hughes received a check for $546,549,171, making the sale one of the largest stock transactions in history. By a curious irony, Hughes owed this great good fortune to his enemies—the men who had forced him to put his stock in trust back in 1960. Under new management, TWA had rolled up record profits, more than $215 million in the last five years, or more than double the profits the airline earned in Hughes’s fifteen-year reign.* The airline’s stock was selling at near its all-time high. Had Hughes sold out in December of 1960, when the lenders forced his hand, and when TWA stock was going for about $13 a share, he would have come away with a check for about $85 million. His enemies had given him a $460-million windfall. Even so, there was no rejoicing at Bel Air. There were still the two TWA lawsuits—in federal court in New York, where a special master was conducting hearings to assess damages against Hughes, and in the state court in Wilmington. In addition, the incredible profit from the stock sale created a special problem for Hughes. Not only would he have to pay a substantial federal capital-gains tax on his more than half-billion dollars, he also faced a stiff California income tax.

For years, Hughes had been feuding with California tax authorities, who insisted that he should pay the state income tax. Even though he had lived almost continuously in Los Angeles since 1925, Hughes always maintained that he was a resident of Texas and not subject to the California tax. “I am a Texan and always will be,” he had protested in 1944 to one California tax man.72 Not buying the argument, California levied the tax, and Hughes, under protest, paid. But now, if he remained in the state he would face a tax bill running into the millions of dollars. As he often did when he was anxious about taxes, Hughes turned for advice to Mickey West, his tax lawyer in Houston. West prepared a list of states and foreign countries with favorable tax structures, and while West did not “presume” to tell Hughes where he should live, he did stress that it was “highly advisable that he physically depart from California.”73

And why not? There were no compelling reasons to remain in California, certainly no business reasons. Hughes no longer met anyone from the outside world; his own men communicated to him by memoranda, which, of course, he could receive anywhere. Hughes considered a number of potential locations—the Bahamas, the Mediterranean, England, Las Vegas—finally settling, incredibly, on Boston, a city he had known only slightly as a student in the Fessenden School forty-six years ago. Equally surprising, he did not want to fly. He wanted to go by train.

Hughes had George Francom call Robert Maheu to work out the security and transportation. Maheu lined up two private Pullman cars and began the complicated negotiations with several railroads for transporting the cars cross-country. The aides began to worry. Hughes had not told them why he was leaving California or what his plans were. He told the newest aide at Bel Air, Howard L. Eckersley, only that he wanted to move. The thirty-nine-year-old Eckersley, another Mormon, had joined the aide corps in 1964 after Levar Myler suffered a serious heart attack. Eckersley required no orientation: he was very familar with how to attend to Hughes. He had once operated the movie projector in Bungalow 4. Like his co-workers, Eckersley had a lackluster record before going to work for Hughes. Raised in Utah, he had attended Brigham Young University, the University of Washington, UCLA, and the University of Utah twice, accumulating credits in industrial psychology but no degree. Afterward, he worked for a finance company and then spent three years as an industrial psychologist for the state of Utah. Feeling “dead-ended,” he talked to a friend who worked for Hughes Productions in Hollywood and in 1957 went to work in Operations as a message clerk. Like Holmes, Crawford, and Francom, Eckersley could talk about aviation with Hughes. He was an amateur pilot.

None of the aides wanted to leave California. They were unsettled by the idea of traveling three thousand miles to a new place of work for an indeterminate length of time, without their families. As usual, there was no way of knowing how long Hughes might stay in Boston, but they feared the worst. Several remembered Holmes’s unhappy Montreal-Bahamas experience in 1957, when Hughes had stretched a trip of “seven to ten days” into six months. By mid-July, Maheu had completed arrangements for the journey. The two private railroad cars, under tight security, sat ready at the Union Pacific terminal in Pomona, a suburb in eastern Los Angeles County. Not a word had leaked that the reclusive industrialist was about to make a cross-continent journey. On the night of July 16, 1966, Maheu passed word to Bel Air that everything was set.

The next night, Hughes, Holmes, Crawford, Francom, and Eckersley drove the fifty miles from Bel Air to Pomona to board the train. It was the first time Hughes had been outside in four and a half years.