CHAPTER 20

LIFE IN EXILE

HOAX

TUESDAY, December 7, 1971, was like any other day in the penthouse suite at the Britannia Beach Hotel on Paradise Island. At 6:45 A.M., Hughes ate a piece of chicken and began watching an Agatha Christie whodunit, Ten Little Indians. An hour and twenty minutes later he counted out eight one-grain codeine tablets, put them in his syringe, added a few drops of water, and injected the solution into his arm. That afternoon he finished watching Ten Little Indians, went on to a western, Tension at Table Rock, took twenty-five milligrams of Valium, and fell asleep.1

In New York City that day, at the offices of McGraw-Hill, Inc., Albert R. Leventhal, a vice-president, announced a publishing coup: McGraw-Hill had acquired “world publishing rights to a 230,000-word transcript of taped reminiscences of Howard R. Hughes.”2 Leventhal said the autobiography of the reclusive industrialist—based on almost one hundred taping sessions—would be published March 27, 1972, and that Life magazine would serialize the book in three installments of ten thousand words each, beginning March 10. Hughes had spent the past year, Leventhal said, working on his memoirs with Clifford Michael Irving, an American novelist living on the Spanish island of Ibiza. The surprise disclosure was accompanied by a press release that McGraw-Hill said had been prepared by Hughes himself to explain his decision to write the book. It stated, in part, “I believe that more lies have been printed and told about me than about any living man—therefore it was my purpose to write a book which would set the record straight.”3

Within hours of the McGraw-Hill announcement, a Hughes Tool Company spokesman branded the autobiography a hoax. Clifford Irving, with eight books to his credit, charitably brushed aside the tool company charge, observing that it “was not malice on their part, it was ignorance. They didn’t know a damn thing about it.”4 McGraw-Hill and Life, among the most respected publishers in the country, stood firmly behind the book. “We never dealt with the Hughes Tool Company,” Donald M. Wilson, vice-president for corporate and public affairs at Life, told reporters. “It doesn’t surprise us that they know nothing of this since Mr. Hughes was totally secretive about the project. We are absolutely certain of the authenticity of this autobiography and we wouldn’t put McGraw-Hill’s and Life’s name behind it if we weren’t.”5 To further authenticate the book, Irving delivered to McGraw-Hill a handwritten memorandum from Hughes affirming the validity of the work, and Osborn Associates, a nationally recognized firm of handwriting experts, concluded that the memorandum was indeed written by Howard Hughes.

Throughout the controversy, an oblivious Hughes continued to watch his films—Deadlier than the Male, The Wrecking Crew, No Highway in the Sky, Bullet for a Badman, and Gunfight in Abilene among others—inject himself with narcotics, and gulp tranquilizers. There were occasional other concerns and instructions dutifully entered in the logs by an aide so that the next shift would be current. On December 12, the subject was pills: “Have Carl or Gordon count out the medicinals so we do not touch bottles. They can be prepared in advance and left in cup in refrigerator.”6 On December 21, pajamas: “He wants his P.J. top neatly folded and placed on his table to the left of the chair.”7 On December 23, it was his pillow: “His head pillow is to be inserted with the hard blue-green pillow next to his back and the open end of the pillow case on his right (not the left as before). Also, carry the pillow by the bottom seam.”8 On Christmas Day came desserts: “Wants to start orange tarts again. Also wants to change the Napoleons so there is cake between custard rather than the flaky pie crust material they now have. The custard and frosting should remain as is.”9 And on January 2, the movies: “HRH says not to get any more Italian westerns.”10

The McGraw-Hill announcement of the autobiography had meanwhile thrown the Hughes organization into turmoil. Those in control knew the book was an elaborate hoax. But how to prove it? There was no way that Hughes could even briefly leave his institutional surroundings and make a public appearance to deny authorship. Although tool company officials continued to insist that Hughes had not written any book, they failed to produce the hard evidence that would discredit Irving. The resulting stalemate would require some dramatic act to convince a skeptical public. The vehicle finally settled on was a telephone interview to be conducted by seven reporters who had known Hughes before he went into isolation and thus could identify his voice and ask questions designed to trip up an impostor. The reporters selected to question the industrialist over a three-thousand-mile telephone hookup between the Britannia Beach Hotel in the Bahamas and a makeshift studio at the Sheraton-Universal Hotel in Hollywood were James Bacon of the Hearst newspapers, Gene Handsaker of the Associated Press, Gladwin Hill of the New York Times, Marvin Miles of the Los Angeles Times, Roy Neal of NBC (who was to act as moderator), Vernon Scott of United Press International, and Wayne Thomis of the Chicago Tribune.

The interview posed certain risks. Hughes might display a telltale sign of his mental state. Yet if the questions were none too probing or hostile, he probably could make it through without any unfortunate disclosures. It was reasonable to expect that the questions would not be searching. The reporters had known Hughes in happier days, before he went into seclusion. Then, too, there was Hughes’s memory. Neither age nor his psychological disorders had affected his remarkable powers of recall, especially about airplanes, a subject the newsmen were sure to focus on since all had known him when he was an active pilot.

The date set for Howard Hughes’s first meeting with the press in more than fifteen years was Friday, January 7, 1972. At 3:15 A.M. that day, Hughes began watching the Len Deighton spy thriller Funeral in Berlin. He watched the first reel of the film, the second reel, the third reel, and then all three once again. At 12:45 P.M. he picked up his cache of narcotics, counted out eight one-grain codeine tablets, dissolved the tablets in water in his syringe, and injected himself. He looked at Funeral in Berlin one more time and then at 6:45 P.M.—exactly six hours after he had shot up—Howard Hughes picked up the telephone and met the press.11

“Good afternoon, Mr. Hughes,” said Roy Neal.

“Good afternoon to you,” Hughes replied.

“One question all of us have at the outset is, where are you speaking from right now, sir?” Neal asked.

“Paradise Island,” Hughes said. “Nassau seems to be a more widely known name. I notice accoutrements here at the hotel [say it] is called Paradise Island, Nassau. That must be because Nassau is a more widely known name than New Providence. But in truth, New Providence is the main island here in this group, and Paradise Island, which used to be called Hog Island, is a part of that group, and that is where I am.”12

The voice was older, the speech more hesitant, but there was no mistaking Howard Hughes. As Jim Bacon observed when his turn came to ask the questions, “I have heard that voice so many times, and the minute you started talking I knew it was Howard Hughes.”13 Just as expected, Hughes handled the aviation questions with the same ease he once employed flying planes. When the subject of his design contributions to Lockheed’s Constellation came up, he was prepared to speak for hours:

I remember clearly the plywood cockpit and this feature that I am discussing—Oh, and another thing there that would be clearly remembered by everyone who worked on that cockpit, was my continual complaints about the width, vertically, of the clear area of glass in the windshield. In other words, I was concerned with the visibility, and there was an everlasting struggle between the engineers of Lockheed who wanted better aerodynamic qualities, and they wanted to keep the cockpit as drag-free as possible. They kept pulling the roof of this windshield down and limiting the total amount of clear glass; do you follow me? And when we finally agreed to a compromise, which was a hard-fought battle, then I was either away from Los Angeles, or Burbank, or where the mock-up was located, for a period—or I didn’t see it for a while—and when I came back, I discovered that they had taken the dimensions that I had agreed upon and made it the dimensions of the total frame itself, so that, in other words, it was not the dimensions of the clear glass at all, it was the dimensions of the clear glass plus about three-fourths of an inch, at least, maybe more, of metal into which this clear glass was clamped, which, of course, cut down the vertical arc of visibility or width of visibility appreciably.14

On and on Hughes talked, a memory machine.

But the machine only remembered certain things. His encyclopedic recall of the aircraft he was so closely associated with—the H-1, the D-2, the flying boat, the Constellation—overshadowed an astonishing failure to answer correctly test questions the reporters asked on a variety of nontechnical subjects.

“Here is a question, one question that we thought you might be probably the only person who would know the answer to, offhand,” Gladwin Hill began. “During your development of the Constellation airplane, you were assisted at some points by a professional pilot whose last name was Martin. Do you remember what his first name was, and what his wife’s occupation was?”

“I don’t think I can help you with this Martin,” Hughes said candidly. “I don’t think I remember Mr. Martin, but I can tell you an awful lot about those [Constellation] mock-up discussions.”

Hughes could not answer Wayne Thomis’s test question either. “I would like to take your memory back a ways to the time of your flights in 1937 and 1938,” Thomis said, “and ask you—the man who assisted you in setting up a good deal of this, particularly with the timers and the FAA, was a man who was an executive with AVCO [Aviation Corporation] and I’m wondering if you remember his name.”

“No,” Hughes said forthrightly. Even when Thomis supplied the man’s first name, Hughes still drew a blank. And he fared no better with Marvin Miles’s test question. “I’d like to ask you one identification question,” Miles said. “I’m sure that you can answer very quickly, and then one other on a larger subject. At the time of your ’round-the-world flight when you—just before you took off from Floyd Bennett Field, a superstitious woman placed a traditional good luck charm on your airplane. I’d like to know if you recall what it was, and where she put it?”

“No, I don’t recall, and it certainly happened without my knowledge,” Hughes said.

“No, sir. You spoke of it in a speech to the Washington Press Club when you returned,” Miles said. “You said that a woman placed a wad of gum on the tail.”

“Well, I want to be completely honest with you. I don’t remember that,” Hughes said.

But perhaps the most devastating failure came when Hughes was asked whether he remembered General George, who had managed Hughes Aircraft Company during its transition from a Hughes hobby to an important defense contractor.

“Well, he was just a friend,” Hughes said. “He never worked for me, did he? I don’t remember General George ever working for me.”15

Hughes’s inability to answer the test questions, although vastly puzzling at the time, was not out of character. He had possessed such charm in the early years that it was assumed by all who met him that he was like other men. If he was somewhat shy and eccentric, he seemed nonetheless to relate well to men and women. The truth is that Hughes never related at all to other people. Only mechanical objects, especially airplanes, or technical matter left an indelible mark on his mind.

Still, despite the memory lapses and the fact that Hughes had not dealt with reporters in years, he played the press conference like a seasoned politician, fielding effortlessly those questions unrelated to people, reeling off one answer after another in his low-keyed, convincing, occasionally wry style. That many times his answers bore scant resemblance to the truth no one seemed to notice. After scoffing at published reports that when he left Las Vegas he weighed less than a hundred pounds, his hair trailed down his back, and he had exceptionally long fingernails (all of which was true), Hughes said he intended to end his self-imposed isolation to put such rumors to rest. “I will tell you one thing,” he said. “I am rapidly planning to come out of it. In other words, I am not going to continue being quite as reclusive, as you call it, as I have been because it apparently has attracted so much attention that I have just got to live a somewhat modified life in order not to be an oddity. I am getting ready to embark on a program of convincing the public that these extreme statements are absurd.”16

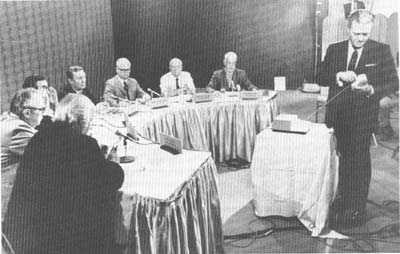

The 1972 telephone press conference. Around the table clockwise are Jim Bacon of the Hearst Newspapers, Marvin Miles of the Los Angeles Times, Vernon Scott of United Press International, Roy Neal of NBC News, Gene Handsaker of the Associated Press, Wayne Thomis of the Chicago Tribune, and Gladwin Hill of the New York Times. Dialing the telephone is Richard Hannah, a Hughes public relations man. Wide World Photos

When questioned about rumors that he chose not to meet people personally because of a germ phobia, Hughes said, “I come in contact with everybody from here to Salt Lake City and Los Angeles and back. I have got a staff that commutes regularly across the country, and I’m in proximity to them constantly, and if I have any fear of contagion, they would certainly bring it here. Anyway, I don’t think this is a particularly contagious-free area that I’m in anyway.”17

To a proposal that he have a face-to-face meeting with the press, Hughes said, “I definitely expect to do it. I have intentions to do it.” Was he considering a return to motion picture production? “I would like to. I have always thought that movies and motion pictures would be something I could do even after my last days, so to speak. I have always thought that in the later years of my life I would like very, very much to make motion pictures that would be worthwhile.” Had he any plans to resume flying airplanes? “Yes. Positively. I definitely expect to recommence the program of flying.”18

When the questioning got around to the purpose of the interview, the Clifford Irving book, Hughes expressed astonishment. “As Mr. Davis said, this must go down in history. I only wish I were still in the movie business, because I don’t remember any script as wild or as stretching the imagination as this yarn has turned out to be. I’m not talking about the biography itself, because I have never read it. I don’t know what’s in it. But this episode is just so fantastic that it taxes your imagination to believe that a thing like this could happen.” As for Clifford Irving himself, Hughes was quite explicit: “I don’t know him. I never saw him. I have never even heard of him until a matter of days ago when this thing first came to my attention.”19

Hughes professed to be at a loss to explain the motive for the Irving book, but he did rise to a question about Robert Maheu. Could, asked one reporter, the book be “a carefully structured plot by the Maheu-Hooper interests to discredit” him? Hughes replied quickly, “My attorney thinks that it could be.” Such was the depth of the bitterness within the organization that Hughes’s only display of anger was directed not at Irving, but at Maheu. Alluding to a lawsuit Maheu had brought against the Hughes Tool Company challenging his dismissal, Hughes charged that “everything he has done, everything short of murder, as a result of being discharged, I don’t suppose any disgruntled employee who was discharged has ever even come close to Mr. Maheu’s conduct.” Asked why he had fired Maheu, Hughes—reflecting the stories he had been fed repeatedly over the past two years—announced flatly: “Because he’s a no-good dishonest son-of-a-bitch, and he stole me blind. I don’t suppose I ought to be saying that at a news conference, but I just don’t know any other way to answer it. You wouldn’t think it could be possible, with modern methods of bookkeeping and accounting and so forth, for a thing like the Maheu theft to have occurred, but, believe me, it did, because the money’s gone and he’s got it.”20

Throughout the two-and-a-half-hour interview, this was Hughes’s only serious blunder.* Otherwise, Hughes conducted himself superbly, only stumbling over those questions relating to people he had once known and long since forgotten. It had been agreed before the interview that the questions and answers would be transcribed and made public Sunday night. On Monday morning, January 10, 1972, newspapers across the country carried the Hughes interview on their front pages, and radio and television stations broadcast excerpts. Within a month, Clifford Irving acknowledged that the Hughes autobiography was the product of his own imagination.

Although Hughes had emerged with his image intact, the press conference touched off another crisis for his organization. So much publicity had swirled about Hughes and his alleged autobiography that the opposition political party in the Bahamas saw an opportunity to embarrass the government of Premier Lynden O. Pindling, the Bahamas’ first black ruler. Not long after the press conference, Cecil Wallace Whitfield, leader of the Free National Movement, announced that he intended to submit a series of questions to the Pindling government concerning the immigration status of Hughes and his aides. Hughes’s residency permit had long ago expired. His staff did not have work permits—all foreigners employed on the islands were required to have them—and they came and left the Bahamas as they pleased. Faced with an election in the coming year, Pindling moved to squelch any controversy by sending immigration officers to the Britannia Beach Hotel to make an inquiry. But when the officials arrived at the hotel on February 15 and asked permission to enter the penthouse, the request was denied. While Hughes’s guards outside the ninth-floor suite stalled for time, aides carried Hughes down an outside fire escape to a floor below. When the immigration officers finally were admitted to the rooms, they found four aides without work permits who were immediately deported. When the immigration inspectors left, the remaining aides carried Hughes back up the fire escape, placed him again in his bed, and waited while arrangements were made for an escape from the Bahamas.

Of prime importance was the need to prevent outsiders, especially hostile ones, from seeing or questioning Hughes in his present condition. This delicate task was entrusted to James O. Golden. A onetime Secret Service agent, Golden had worked in the office of Vice-President Nixon during the Eisenhower administration and had handled security for Nixon during the 1968 Republican National Convention. Later, Golden went to work for Intertel, and shortly after Intertel was retained by Gay and Davis, Golden joined the Hughes Tool Company as security chief for the Nevada properties.

To get Hughes off the islands quickly and in secret, Golden chartered an eighty-three-foot luxury yacht, the Cygnus, owned by a Baltimore advertising executive. At 5:50 A.M. on Wednesday, February 16, the aides placed Hughes on a stretcher and carried him down the hotel’s outside fire escape to the waiting yacht. The skipper, Captain Bob Rehak, took note of Hughes’s shoulder-length hair and his scraggly beard, but a white sheet covered the rest of his body. At first Hughes was left lying on the stretcher in the pilot house, but as the sea began to roll, and the stretcher with it, the aides carried Hughes to a couch in the salon. At one point, Hughes stood up and Rehak saw that he was wearing a bathrobe and nothing else. “He didn’t have a damn stitch on underneath, no pajamas, nothing,” Rehak said. “And that’s when I first noticed his long toenails. They were so long they curled up. Never seen anything like that in my life. I had to look twice. Craziest thing I ever saw. He had on sandals.”21

Nearly twenty-two hours after the Cygnus left the Bahamas, it docked at Sunset Island No. 2 in Key Biscayne Bay, where the Hughes organization had long maintained a rented house. There the boat and its secretive passengers were greeted by United States Customs agents who had been summoned under a special arrangement worked out by Golden. After a cursory inspection of the Hughes party, the agents quietly left. At 7:30 A.M., three and a half hours after its arrival in Florida, the Hughes caravan boarded a leased Eastern Airlines jet and flew to Nicaragua.

Golden had done his work well. In Managua, Turner B. Shelton, the United States ambassador to Nicaragua, had gone right to the top, securing the cooperation of that country’s military strongman, President Anastasio Somoza. Delighted to be of service to one of America’s most famous and wealthiest citizens, Somoza readily waived immigration and customs formalities for Hughes and his aides, an essential courtesy since Hughes did not have a valid United States passport. In addition, Somoza guaranteed that Hughes would be afforded maximum privacy. When reporters began questioning government officials after picking up rumors of Hughes’s presence in the country, Nicaragua’s immigration chief matter-of-factly declared that “officially, nobody named Howard Hughes has arrived.”22

Once again, the Hughes entourage occupied an entire hotel floor, this time the eighth floor—the top, or the ninth floor, was a restaurant—of the 210-room Intercontinental Hotel located five blocks from the center of town. The hotel had been built to command a panoramic view of Lake Xolotan and the presidential palace, with mountains and smoking volcanoes in the distance. The windows in Hughes’s suite were nevertheless sealed at once. The Hughes retinue remained in Managua only twenty-five days, leaving on March 13, the same day that Clifford Irving, his wife Edith, and associate Richard Suskind, pleaded guilty in New York to criminal charges growing out of their bold scheme to bilk McGraw-Hill of $750,000. Before leaving Managua, however, Hughes broke his isolation of fifteen years to meet for about an hour with two outsiders—General Somoza and Ambassador Shelton—aboard a leased airplane. George Francom, an aide present during the conversation, recalled that Hughes assured Somoza “how he liked his country and how appreciative he was of the courtesy of the invitation down there.” Repeating a refrain from the telephone interview two months earlier, Hughes told the general that “he regretted he had fallen into his reclusive ways and he was definitely planning on changing his habits.”23

When Hughes said good-bye around midnight, Shelton and Somoza left the cabin and the jet flew off toward the United States, refueling in Los Angeles—the first time Hughes had been back in that city since he left for Boston six years earlier—and took off forty-five minutes later for the final destination, Vancouver, British Columbia. When the aircraft arrived, Hughes was whisked to the twenty-story Bayshore Inn, whose top floor had been reserved. As soon as he was in his suite overlooking Vancouver harbor, the windows were, as usual, sealed.

Meanwhile, back in Nicaragua, when reporters learned that Hughes had met with two strangers, they besieged Shelton with questions. The ambassador was forthcoming. “He looks extremely well,” Shelton said. “He was wearing a short beard that covers his face and builds into a Vandyke on his chin. His hair is cut short.”24 As for Hughes’s isolation, Shelton said that the industrialist had explained that he was a compulsive worker and did not want to be interrupted by visitors and telephone calls.

The man Shelton saw differed markedly in appearance from the man Captain Rehak had seen on his yacht a month earlier, and there was a good explanation. Forty-eight hours before Shelton and Somoza met Hughes, Mell Stewart had cut Hughes’s hair and trimmed his beard—for the first time in several years—and cut his toenails. In addition, Hughes had taken one of his infrequent showers.25

Following Hughes’s arrival in Vancouver, Richard Hannah of Carl Byoir & Associates, whose principal responsibility as public-relations counselors to Hughes was to make certain that little information was made available about their client, issued a perfunctory press release. “Mr. Hughes is in Vancouver on a business trip,” Hannah announced. “There is no indication of the nature of the business or of how long he intends to remain there.”26 As was the case with so many publicity releases distributed on Hughes’s behalf, this was more than a little misleading. Whatever the reason for shipping Hughes from Managua to Vancouver, it had nothing to do with business. In fact, the groundwork for the most momentous business undertaking in the history of the Hughes empire was being laid at that time not in Vancouver, but more than a thousand miles away, in Los Angeles and Houston.

THE $350-MILLION GIVEAWAY

A decision had been reached by those now running the empire to sell the oil-tool division of the Hughes Tool Company, fountainhead of the family fortune. This family business, founded by Howard Hughes Sr. in 1909, had dominated the American oil-drilling industry for more than a half century, by 1950 controlling about 85 percent of the drill-bit market. More importantly, the oil-tool division had provided young Howard with the abundance of riches required to finance his unsuccessful ventures in filmmaking, airplane manufacturing, and hotel and casino management. No other division of the empire was significantly profitable.

The decision to sell the oil-tool division, according to testimony by Bill Gay, was made at a meeting he attended with Raymond Holliday and Chester Davis. The stated purpose of this gathering of top Hughes executives was to determine how to pay the $145.4-million judgment, plus interest, that had been entered against Hughes and in favor of TWA in the United States District Court in New York. Only a few years earlier Hughes would have had ample cash, or readily marketable securities, to cover the judgment. But no longer. His money, under the management of others, was disappearing at an alarming rate. Still, the assembling of the Hughes high command seemed premature. After all, it would be months before the TWA case was argued before the United States Supreme Court, more months until the court handed down its ruling, and of course it was possible that Hughes would win. As Gay himself put it, “We felt confident that we were going to prevail.”27 Nevertheless, Gay said, the group opted to sell the oil-tool division. Gay did not take any notes during the meeting in which the unprecedented sale plan was formulated, and he could not recall whether either of the other participants had prepared a memorandum proposing other alternatives for raising cash. “I do not believe that we prepared a white paper,” he said.28

With the agreement to sell concluded, it fell to Holliday and Davis to tell Hughes. Although he had been representing Hughes for more than a decade now, Davis had yet to meet Hughes face-to-face, and Holliday had not seen him since the late 1950s. Even though he was the chief operating officer of all Hughes’s enterprises, Holliday had not had a telephone conversation with Hughes in years, and did not even send mail directly to him. Any report or message from Holliday to Hughes was placed in an envelope and mailed to one of the aides. According to Gay, either Holliday or Davis advised Hughes of the decision to sell Hughes Tool, which one—and how—is not known. What is certain is that neither met with him. On at least two occasions that spring and summer, Holliday flew to Vancouver to discuss arrangements for the sale of the oil-tool division, and both times Hughes either refused or was mentally unable to see him. In any event, Holliday, Gay, and Davis pushed ahead, retaining Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith to handle the public stock offering. By the time Hughes began to object, it was too late.

Although Hughes was doing less work than ever, Romaine Street sent another aide, James H. Rickard, to Vancouver to join the industrialist’s personal staff, bringing to six the number of male attendants now looking after Hughes around the clock. Born November 20, 1919, at Powell, Wyoming, Rickard had studied mechanical engineering and business for three years at the University of Wyoming and Montana State College, and then had compiled a checkered employment career before joining Bill Gay’s band of Chevrolet drivers at Romaine Street in October of 1953. After serving as a pilot during the Second World War, Rickard was a construction worker in California, ran a drive-in movie theater in Montana that was a casualty of the state’s climate—“We opened on Memorial Day and it snowed about a foot and a half two weeks later”—sold life insurance in Arizona, and finally returned to California to go to work for Hughes Productions.29 Like so many others at Romaine Street, Rickard was hired through his Mormon connections—his brother-in-law was active in church affairs with Gay. Then in 1957, after four years as a Hughes driver, Rickard took a one-year leave of absence to try his hand at managing a logging and sawmill operation in Bozeman, Montana. That business failed, too—“The lumber market price dropped about $50 about two months after we started”—and Rickard hurried back to Romaine Street.30

In August of 1972, the Hughes caravan, which had already moved twice in seven months, unexpectedly pulled up stakes and returned to Nicaragua, vaguely citing Canadian taxes as the reason for leaving. On Tuesday, August 29, Hughes and his aides boarded a jet and flew back to Managua, again checking in at the Intercontinental Hotel. Nicaragua’s ruler was gratified by Hughes’s return. “I am very pleased that Mr. Hughes has accepted my personal invitation to once again visit with us,” General Somoza said, assuming that Hughes was in Managua by his own choice. “I know that all Nicaraguans will join in extending to him our traditional hospitality.”31 The general did not see Hughes this time. Nor did Raymond Holliday, who flew to Managua only to be turned away a third time.

Hughes probably lacked the strength to be truly difficult, as he would have been in healthier days, but he nevertheless made it clear that he did not want to part with the tool company. He had not visited the Houston plant, which now sprawled over eighty-four acres and employed more than four thousand people, since 1938. He had not met with any tool company officers in fifteen years. He knew almost none of the top executives. Yet his feelings for the company ran deep. He regarded it as a family monument, a living testimonial to his father. If Hughes had one unmistakable emotional concern in all his life, it was the preservation of the oil-tool division of Hughes Tool Company. In his 1925 will, Hughes had pledged to preserve the tool company and carry out the policies of his father “so long as I shall live.”32 He had dangled the tool company as bait before eager investors for three decades, but never seriously considered selling. To have done so would have betrayed the memory of the father he revered. As Hughes himself once put it, an aide recalled, “his father would probably never forgive him if he sold it.”33

His feeble protests notwithstanding, by the late summer of 1972 Hughes was being swept along by a tide of legal and financial paperwork leading to the inevitable sale. Early in September, Securities and Exchange Commission officials in Washington exchanged memoranda on the transaction, which was subject to SEC review since it involved a public stock offering. On September 13, Raymond Holliday signed documents in Houston establishing a new Hughes Tool Company that would be publicly owned, and the following day the incorporation papers were filed with the Delaware secretary of state.

Because of recurring rumors that Hughes was incapacitated and his empire controlled by anonymous underlings, the Securities and Exchange Commission wanted firm evidence that he was alive and well and truly wanted to sell his company. Hughes was of course resisting this, and it was not until September 16, two weeks after the SEC began to study the proposed sale, and two days after the formation of the new Hughes Tool Company, that one of the aides, following a conversation with Hughes, entered this notation on the logs in Hughes’s suite: “HRH said that he wanted to sell the OTD [oil-tool division] and would sign the papers in the presence of the Merrill Lynch people.”34

Moving with unprecedented speed, the clique pushing the sale set September 24 as the date for the viewing. It was agreed that Julius H. Sedlmayr, a group vice-president of Merrill Lynch, and J. Courtney Ivey, a partner in the New York law firm of Brown, Wood, Fuller, Caldwell & Ivey, which was representing the brokerage house, would fly to Managua on Sunday, September 24, and meet with Hughes at 2 P.M.

In the four weeks leading up to the scheduled meeting, Hughes spent his time much as he had in the past two years, injecting himself with narcotics, consuming tranquilizers, and watching movies. There were a few interruptions in the routine, and the usual petty annoyances. On Sunday, September 3, Hughes fell off the toilet and injured his arm and heel. On September 7, he ordered the aides to supply him with “California and Florida orange juice, as well as the Minute Maid,” so that he could make his own taste test. On September 9, he complained that the milk he was being served was not as cold as it had been in Vancouver, and that his pillows were not being folded properly. On September 10, he complained at 8:15 P.M. that his room was too warm, and seven hours later that it was too cold. On September 20 and 21, he submitted to enemas to relieve his constipation.35

During the four weeks, he sat and stared at thirty-five different movies at least once, including Myra Breckinridge, Strange Bedfellows, Executive Suite, and Evel Knievel. One film which had a special hold on him at the time was an hour-and-forty-minute crime thriller, The Poppy Is Also a Flower. Produced for the United Nations in 1966, the film is all about narcotics traffic and drug addiction, and tells the story of how U.N. agents trace the flow of narcotics through the underworld and smash a drug ring. Hughes was mesmerized by the film, with its lively scenes of narcotics agents, drug dealers, and addicts, watching it ten times in the month after he arrived in Managua. A day did not go by without an aide threading the ever-present projector and showing one or two reels of a motion picture. Even on August 29, when Hughes spent most of the day flying from Vancouver to Managua, he still squeezed one film into his schedule. But Sunday, September 24, the day he was to see Sedlmayr and Ivey, Hughes watched no movies. At 5:30 A.M., he swallowed seven of his blue, ten-milligram Valium tablets—twenty-eight times the recommended daily dose for someone his age. As might be expected, he passed out for five hours, then got up, groggily, went to the bathroom, returned to bed, and slept right through the appointed 2 P.M. meeting.36 Sedlmayr and Ivey were then assured that Hughes would see them at 5 P.M. But at five o’clock Hughes was still sleeping, and the meeting had been pushed back to 8 P.M. At 5:30, Hughes woke up, went to the bathroom, then settled into his reclining chair, where he remained for the next three hours. Meanwhile, the aides informed Sedlmayr and Ivey that Hughes would see them at 10 P.M., but that hour, too, came and passed with Hughes still unable to face the men who were going to sell his company.37

Sedlmayr exploded. He told the aides that “he would call the deal off unless he and Ivey personally conferred with Hughes in time to catch a 6:45 A.M. flight back to New York.”38

Still Hughes sat immobile in his chair. Shortly before 1 A.M. on Monday, September 25, he began watching Man in the Middle, a story set in India during the Second World War, depicting the fate of a psychopathic United States Army officer who empties his pistol into a British noncommissioned officer. At 3:45 A.M., Mell Stewart trimmed Hughes’s beard and cleaned him up, a process that took an hour and forty-five minutes. Fifteen minutes later, Hughes, still seated in his reclining chair, received Sedlmayr and Ivey.39 Mickey West, Hughes’s tax lawyer, and Raymond Holliday, who would be the chairman of the board and chief executive officer of the new Hughes Tool Company, had accompanied the Merrill Lynch representatives to Hughes’s suite, but were not invited into the bedroom. For the next thirty-five minutes they sat in the adjoining aides’ office while Sedlmayr and Ivey talked with Hughes. Exactly what took place during those thirty-five minutes is uncertain, but there is no doubt about whose interests were represented and whose were not. Ivey, the Wall Street lawyer, was there to represent Sedlmayr and Merrill Lynch. Mickey West, the Houston lawyer, was there to represent the proposed publicly owned Hughes Tool Company. Only Howard Hughes, who stood to lose one of the most prosperous companies in history, and whose mental condition was diminished by years of drug addiction, was without legal representation. As West put it later, “I don’t know that anyone represented Mr. Hughes personally.”40

A year later, Fortune magazine reported that Sedlmayr and Ivey had “found Hughes, at sixty-six, remarkably unchanged. His black hair now carried a touch of gray and his chin bore a Vandyke that was neatly trimmed; otherwise, he looked pretty much as he had when last seen in public fifteen years earlier.”41 The magazine went on to say that Hughes talked about the tool company “with what at times struck his listeners as nostalgia. Hughes recalled how close he felt to the company and its workers. ‘I want the employes to be treated well,’ he stressed.”42

At any rate, Hughes signed the necessary papers before Sedlmayr and Ivey—his signature was witnessed by Chuck Waldron and George Francom—and they left the bedroom at 6:15 A.M. As they did, Hughes called out to Raymond Holliday, a thirty-four-year veteran of the Hughes organization and the chief executive of the tool company since Noah Dietrich’s firing in 1957, “Raymond, don’t go away. I want to talk to you.”43 But Holliday ignored the call and accompanied Sedlmayr and Ivey to the airport. He would never see Hughes again.

His visitors gone, Hughes resumed movie watching, completing Man in the Middle and going on to The Italian Job, a comedy-suspense film built around the daylight robbery of $4 million in gold ingots from an armored van on the streets of Turin, Italy, and The Adventurers, a Harold Robbins account of the jet set and South American politics laced with sex and pillage. Before the day ended, however, Hughes was having second thoughts about the tool company sale. He fretted about its unseemly haste and wondered whether it might not be delayed until 1973. A postponement this year could be followed by a postponement next year. During his career, Hughes had perfected the practice of delaying decisions until the decisions became irrelevant. He summoned one of the aides and asked him to send a query to Holliday asking why it was necessary to sell the company in 1972. The aide returned to the desk in the office and dutifully recorded Hughes’s request in the log: “How does HRH benefit personally or how does the company benefit whether the stock is sold this year or not?”44 Hughes might as well have whispered into the whirlwind. The scheme to sell the tool company had gained such momentum that it was beyond control. Sedlmayr and Ivey informed the Securities and Exchange Commission that Hughes himself had authorized the sale. When investigators in the agency’s enforcement section raised certain questions about the transaction, the Corporation Finance Division of the SEC, which had processed the paperwork, advised them that the sale had been cleared and was out of their jurisdiction.

The heart of Howard Hughes’s empire, the sprawling Hughes Tool Company works in Houston, shortly before it was sold in 1972. Wide World Photos

Monday, October 16, was like any other day for Hughes in his Nicaraguan hotel room. He watched The Poppy Is Also a Flower once more and A Face in the Rain, swallowed at least six Valium tablets, and fell asleep shortly before noon. In Washington, a registration statement was filed with the SEC providing for the sale of five million shares of stock in a new Hughes Tool Company at $28 a share. The proceeds would total $140 million—less than the company’s pretax earnings over five years during the oil-industry boom of the early 1950s. Under the proposed offering, a new company was to be established called Summa Corporation. All Hughes’s holdings in the existing Hughes Tool Company, including the oil-tool division, would be transferred to Summa. When the stock was to be sold to the public, the newly created Hughes Tool Company would take over the oil-tool division. Summa Corporation would retain all the remaining properties—the Nevada hotels and casinos, the Las Vegas television station, Air West, the Hughes Sports Network, a helicopter-manufacturing division, thousands of acres of undeveloped land, other real estate, and assorted investments. Raymond Holliday would become the chairman of the board and the chief executive officer of the publicly owned Hughes Tool Company. Other longtime Hughes executives also would assume corporate positions in the new company—James R. Lesch, president and chief operating officer, and Calvin J. Collier, Jr., vice-president, secretary, and treasurer. The board of directors would include Ned B. Ball, the president of Merrill Lynch, which was handling the stock offering, and Clinton F. Morse of Andrews, Kurth, Campbell & Jones.

When Hughes learned that the stock in his company was to be sold for $28 a share, he complained to his aides that it should bring $40 or $50. The aides relayed his displeasure to Holliday and Davis. Davis, in turn, “checked it out,” according to Chuck Waldron, and reported back to Hughes that “it looks like we’re getting what is the going price per share.”45

As the weeks slipped by, Hughes was soothed, cajoled, and assuaged time and time again. The message was always the same—it was essential to sell the oil-tool division to satisfy the TWA judgment. No one suggested to him that the sale might not be a wise one. The attitude of Nadine Henley, whose employment with Hughes dated back to 1942, was typical. “If Mr. Hughes wanted to sell something,” she explained later, “he sold it. Mine not to reason why.”46 Hughes, of course, did not want to sell. “But I think he was made to realize,” George Francom said later, “that it was quite necessary or imperative that he do so.”47 Still, Hughes could not understand opposition to delaying the sale for a year. After all, the Supreme Court might overturn the TWA judgment. On December 1, a week before the stock was to be issued to the public, Hughes continued to besiege his staff with questions about postponement. In response to one inquiry, Howard Eckersley typed out a memorandum and handed it to Hughes. The memorandum began, “The OTD [oil-tool division] must be sold this year because it cannot be sold in the same year as the TWA decision.”48 Eckersley, who then was being sought by Canadian authorities in connection with his part in a uranium-mining stock-fraud case, played on Hughes’s obsession with taxes and proceeded to offer a technical—and highly suspect—explanation of why he would receive certain tax benefits only if the company were sold before year’s end.

On Thursday, December 7—seventeen days before Hughes’s sixty-seventh birthday—the five million shares of stock in the new Hughes Tool Company were offered to investors by Merrill Lynch. The stock was snapped up at $30 a share instead of the originally announced $28, giving Hughes $150 million, less underwriting fees and taxes. One week later, on December 14, the last papers completing the transaction were signed and a new Hughes Tool Company, minus Howard Hughes for the first time, commenced business. In his Managua hotel room that day, Hughes again deviated from his customary routine, just as he had the day he was to meet with Sedlmayr and Ivey—he watched no movies. After taking six ten-milligram Valium tablets at 12:30 P.M., he spent much of the rest of the day sleeping.

When the sale of the tool company had first been announced in October, there was, as usual, no official statement from Hughes. However, a member of his staff devoted to perpetuating the Hughes legend was enthusiastic. “The old man’s timing has always been good,” the Hughes man asserted. “He’s got some ideas we don’t know about yet.”49 On the surface there was evidence to support the aide’s statement, at least as far as the timing of the sale was concerned. Since 1924, when Hughes took over the tool company following his father’s death, the company had produced $745.4 million in profits before taxes. But in recent years profits had declined sharply. Earnings after taxes had once reached $20 million a year, but for the years 1967 to 1971, the oil-tool division’s net income averaged slightly under $5 million. The decline was accompanied by a steep downturn in the company’s return on sales. Net income once ran better than 27 percent of sales, but by 1971 the figure was a dismal 5.7 percent.

Because the company’s principal products were drilling bits, used primarily in the oil and gas industry, and tool joints, used to connect sections of oil-and gas-well drill pipe, its fortunes were tied to the health of the oil and gas industry.50 From 1962 to 1971, the number of wells drilled in the United States fell from more than forty-five thousand to twenty-seven thousand—only about half the number of wells drilled during the 1950s.51 The number of drilling rigs at work around the country plunged from 1,636 in 1962 to 975 in 1971. Two of the patents on the Hughes bit and the patent on the tool joint thread were due to expire the following year.52

Surely 1972 was a good time for Howard Hughes to sell his father’s business. As Newsweek put it, “In some respects, it looked as though Hughes was unloading an albatross.”53 But business statistics can be immensely deceptive. Ever since Spindletop the oil business had run in cycles, the prosperous years followed by the lean as regularly as night follows day. Even as Merrill Lynch prepared its stock prospectus for the new Hughes Tool Company, recovery in the oil industry was well under way. Drilling activity was on the upswing, as measured by the tool company’s own drilling index, the bible of the industry. And the increased drilling was already translating into rising profits. During the first seven months of 1972, the tool company’s net income totaled $5.9 million—up 136 percent over its earnings of $2.5 million during the same period in 1971.

One year after Hughes’s stock in the Hughes Tool Company was sold for $30 a share, it was trading at $90. In less than three years, the stock—after a 100-percent stock dividend—was selling at $50 a share. A weakened, confused, and feebly resisting Hughes by this sale had lost more than a third of a billion dollars in the short run. Over a longer span, the tool company sale was even more costly. In the five years after Hughes Tool went public, its net income amounted to $162.5 million—or $12 million more than Hughes received.

January of 1973 brought a huge but not unexpected irony that made the oil-tool division sale all the more poignant. Twenty-seven days after the sale, the United States Supreme Court ruled in favor of Hughes in his twelve-year legal war with TWA. The $145-million judgment was cancelled, and with it all necessity, or pretense, for the sale of his tool company. But Hughes’s catastrophic loss was the gain of others. At fifty-eight, Raymond Holliday, the onetime accountant, severed all ties with Hughes and became chairman of the board and chief executive officer of the publicly owned Hughes Tool Company. Over the next two years, his combined salary and bonus rose 33 percent, from $204,105 to $271,324. More significantly, Holliday secured a fringe benefit that Hughes had stubbornly refused to grant—stock options. In less than three years, Holliday’s options were worth more than $1.5 million. Other tool company veterans fared proportionately as well.

Now that Holliday, Calvin Collier, and other oil-tool managers were all working for the publicly owned Hughes Tool Company and no longer associated with Hughes, the top officer in Hughes’s empire was Frank William Gay. The quiet Mormon had outlasted and outmaneuvered every executive who had sought the top job. His influence and power now reached all corners of the empire. He was the executive vice-president, the highest operating officer in Summa Corporation, the conglomerate that was the holding company for nearly all Hughes’s enterprises. He was a director and a member of the three-member executive committee of Summa. (The others were Nadine Henley and Chester Davis.) He was half of a two-man executive committee (the other was Chester Davis) that ran the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. As the sole stockholder of Hughes Aircraft Company, the medical institute held final authority over operations at one of the country’s ten largest defense contractors with annual revenue of more than $1 billion. Gay was a director of Sands, Inc., Harolds Club, Inc., Hotel Properties, Inc., Sands Country Club, Inc., Desert Inn Improvement Company, and Hughes Sports Network, Inc. He was a vice-president, director, and a member of the three-member executive committee—with Miss Henley and Davis—of Hughes Air Corporation, the company that controlled Air West. And he had further tightened his control over the channels of communication to Hughes and the aides who lived with Hughes around the clock.

Two of those aides fared quite nicely with Gay’s rise in the empire. Levar Myler, the onetime burr-and milling-machine operator who had gone to work for Gay at Romaine Street in 1950, became a director of Summa. He also received a substantial raise, his combined salary and bonus jumping from $60,000 in 1972 to $75,000 in 1973 for work that still consisted largely of receiving and transmitting messages to and from Hughes. John Holmes, the onetime cigarette and wax salesman who had gone to work for Gay at Romaine Street in 1949 and who went on to become Hughes’s chief narcotics courier, was elevated to the Summa board and given even a higher salary than Myler. Both Myler and Holmes were added to the gaming licenses for Hughes’s casinos in Nevada.

Gay also moved other faithful Romaine Street associates into corporate positions. Kay Glenn, his general administrator, became a director of Hughes Air Corporation. Paul B. Winn, an attorney who worked out of Romaine Street and later Gay’s Encino office, and Rand H. Clark, another aide who followed Gay from Romaine Street to Encino, became assistant secretaries of Hughes Air Corporation. Winn also became an assistant secretary of Summa. Like Gay, all were Mormons.

After having yielded to pressure to sell the oil-tool division, Hughes was both annoyed and puzzled by the name given to his new company. It was a sign of how little control he exercised now, as well as the contempt those running the empire had for him, that they named the company Summa Corporation without seeking Hughes’s advice or consent. When he first saw a slip of paper with the name Summa on it—a name chosen by Gay—he asked, “What the hell does that mean? How do you pronounce it? I don’t even know how to pronounce it, Summa, Summa, or what is it?”54 Repeatedly, Hughes complained. He wanted the name changed. At one point he issued orders that no more stationery be printed with the name Summa. “He had in mind using his own initials” as a corporate name, recalled George Francom. The initials HRH “had a dual meaning,” Francom said, “Hughes Resorts Hotels, which he thought would be good.”55 Hughes even dictated a memorandum to Chester Davis asking “why we cannot change the name Summa to HRH Properties.”56 But no one seemed to be listening.

INVALID

By now Hughes was no longer in Nicaragua, but elsewhere, routed by the forces of nature. It was 12:30 A.M. on Saturday, December 23, and Hughes had just called Jim Rickard into his Managua bedroom when the first violent earthquake tremors began to shake the pyramid-shaped Intercontinental Hotel. “He had a large speaker that we used to amplify the movie sound so he could hear and I was just walking by it when it hit,” Rickard recalled later. “I would guess it would be three feet by four feet in size. It was heavy. He was sitting in a lounge chair, in a recliner, with his feet up and I figured it would fall right on his legs and break them, and I grabbed that. The movement was so violent that I probably would have fallen down had I not been holding on to that speaker. After a few minutes, two of the legs cracked off and the table it was sitting on tumbled and I threw it away from him.”57 While Hughes sat impassively in his chair, Rickard rushed back to the aides’ office, where “all the desk drawers had come out and spilled, all the file drawers come out and spilled, and everything just tumbled.”58 Frantically, he placed two telephone calls, the first to his wife in Burbank, the second to Operations at Romaine Street, asking for help. As the lights went out and the tremors continued to rock the building, sending bewildered, half-clothed guests from their rooms into the darkened streets of Managua, Rickard found a flashlight and returned to the bedroom. By this time, falling plaster covered the room and a toppled floor lamp rested across Hughes. When Rickard reappeared, Hughes looked at him and said, “Well, let’s get this mess cleaned up.”59 When George Francom, Howard Eckersley, and Mell Stewart came rushing in to join Rickard, they all urged Hughes, who was wearing only his pajama tops, to get dressed and leave the hotel. “I know all about earthquakes,” Hughes said confidently, “and if you live through the first jolt, then everything’s going to be alright. We’ll stay right here.”60 The aides had no such faith. They finally persuaded Hughes—whose calmness was no doubt due in part to his consumption of the ever-present tranquilizers—to put on a pair of slacks and a sport shirt. Placing the frail industrialist on a stretcher, they carried him down nine flights of stairs and deposited him in the back seat of a waiting Mercedes Benz, where he huddled under a blanket for the rest of the night as the earth opened up and swallowed downtown Managua. Block after block was leveled, nearly six hundred in all. Bodies and debris littered the streets. Other bodies were buried under piles of rubble reaching higher than fifteen feet. Ruptured mains shut off the water supply and fires burned out of control across a third of the city. Communications and electrical service were cut.

The next morning, Hughes’s sixty-seventh birthday, aides drove the Mercedes aimlessly about nearly impassable Managua streets, passing knots of dazed and homeless victims who sat on sidewalks surrounded by their possessions. But most of the survivors clogged roads leading out of the hot, dry capital, taking with them bedding, clothing, and kettles, heading for the homes of relatives in neighboring communities or to emergency campsites being set up around the city. On Christmas Eve, American relief teams began to arrive, bringing with them emergency equipment and medical supplies. A field hospital, flown in from Fort Hood, Texas, was set up on the grounds of General Somoza’s private residence. At the Las Mercedes Airport, emergency flights shuttled in and out, bringing in supplies, carrying away the injured for treatment at hospitals in neighboring Honduras and Costa Rica. One of the few planes that landed without medical equipment or other supplies was a Lear jet dispatched by Romaine Street. Hughes was loaded onto the aircraft, flown to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and then driven to his organization’s rented house on Sunset Island No. 2. On Tuesday, the day after Christmas, he was driven back to Fort Lauderdale, put on a leased Lockheed JetStar, and flown not to Los Angeles, Boston, Vancouver, or the Bahamas, but to London, where he was moved into the penthouse suite at the Inn on the Park, an elegant hotel overlooking Hyde Park and Buckingham Palace. Ninety minutes after Hughes entered his latest bedroom, he was seated in his familiar reclining chair watching a movie, The Deserter, the death and destruction in Managua apparently far from his thoughts. As time and distance separated Hughes and his traveling companions from the destitute survivors of the earthquake, the aides reminisced about the boss’s response under stress. “He was cool, so cool,” Howard Eckersley told a newspaper reporter. “Everyone was saying we must evacuate immediately, but he said no. He wanted to be sure it was absolutely necessary.”61 Although the body count was still going on at year’s end, it appeared that the death toll in Nicaragua would reach six thousand, perhaps higher. Property damage rose to more than $1 billion. Neither Hughes nor those around him looked back, or offered any assistance. Hughes spent the last hours of 1972 watching Dead Eyes of London. Afterward, while he slept through the effects of a codeine injection and six Valium tablets, several thousand miles away a DC-7 cargo plane loaded with twenty-six tons of clothing, food, and relief supplies, lifted off the runway at an airport in Puerto Rico. As the plane headed out to sea and Managua, the engines failed and it plunged into the heaving ocean, killing all five crew members and passengers, including the leader of the mercy mission, thirty-eight-year-old Roberto Clemente, the scrappy Pittsburgh Pirate outfielder and four-time National League batting champion. In Nicaragua, the survivors mourned the death of Clemente and puzzled over the indifference of Howard Hughes, one of the world’s richest men. As a friend of General Somoza lamented, “Hughes still hasn’t sent a damn thing here.” And then he added, perceptively, “I doubt if he will ever come back.”62

Hughes’s failure to respond to this, or indeed to any charitable cause, was consistent with a long, but concealed, tradition. Over the years, Hughes’s public-relations specialists had planted stories extolling his beneficence and his—always anonymous—charitable deeds. It was one of the great Hughes legends woven from fantasy. Even when he was relatively rational, Hughes displayed an amazing lack of concern for other people, unless there was a vested interest. His charity was reserved for those who could return a favor, when the act itself would help him achieve some fleeting ambition, or when it was a legal necessity. As might be expected, his associates now followed the path that Hughes had charted in charitable affairs. On his federal income-tax return for 1965, for instance, Howard Hughes reported charitable contributions totaling $1,375 to the United Crusade, and nothing else.63

Hughes had no sooner settled into his ninth-floor suite at the Inn on the Park than aides began importuning him to meet with Nevada governor Mike O’Callaghan. The Hughes organization’s once-cozy relationship with Nevada gaming officials and politicians had soured in 1971 after Hughes fled the United States. O’Callaghan, a Democrat, was less sympathetic than his Republican predecessor Paul Laxalt, and when Hughes lieutenants submitted revised gaming license applications containing the names of new persons representing the industrialist—notably Bill Gay, Chester Davis, and their allies—gaming officials questioned whether the changes had been made by Hughes or by someone who had seized control of his businesses. In lieu of a face-to-face meeting, they requested a letter in Hughes’s handwriting, and bearing his fingerprints, naming the individuals he wanted in charge of his Nevada hotels and casinos. Hughes submitted the letter, with his fingerprints, and for a while the Nevada authorities were placated. When the Clifford Irving fiasco broke, however, Governor O’Callaghan reiterated his demand for a personal meeting. On January 1, 1972, the aides handed Hughes a message stressing the urgency of the situation:

We are sorry to have to bring this subject up again, but we’re only trying to do the best job we can for you and would not feel that we’d done our best if we hadn’t given you all the facts, so you could make your decision whether you’ll meet with the Governor or not. Mell Stewart has been standing by for a couple of months to do his work (haircut, trim your beard and clip toenails) before he returns home to Utah in a couple of days to see his family. The Governor said that he is planning to be in London on the 5th of January whether you meet with him or not. There can be no further delays. He has put this meeting with you off several times at your request and he now must meet with you before he goes to Legislature. Bill and Chester feels [sic] that if you don’t meet with the Governor when he comes to London on the 5th of January, then you’d better be prepared to liquidate everything in Nevada.64

Hughes still balked at such a meeting. Back in Nevada, gaming officials began sounding tough. Philip P. Hannifin, chairman of the Nevada Gaming Control Board, declared that “recent events focusing upon the authenticity of Hughes’ handwriting should be a clear warning to Nevada that we cannot depend upon such evidence to assure ourselves of the true desire of Hughes,” a reference to the Irving book and McGraw-Hill’s acceptance of a letter purportedly written by Hughes that turned out to be a forgery. Commenting on charges that the state had failed to hold Hughes to the same licensing requirements imposed on all other casino owners, Hannifin noted that “it has been reported that the State of Nevada has entered into partnership with Howard Hughes. If so, it is a partnership that has diminished the integrity and dignity of the state.”65

Relations between the Hughes organization and Nevada officials deteriorated even further when the news media carried accounts of Hughes’s midnight conversation aboard a plane in Managua with Nicaraguan president Somoza. Incensed that Hughes would meet with a Latin American dictator but not the governor of Nevada, gaming authorities refused to approve the requested amendments to the gaming licenses. The dispute dragged on for the rest of 1972 and finally, in London, Hughes consented to meet Governor O’Callaghan during the third week in March of 1973.

Although gradual changes were taking place in his daily routine, nothing major was changing for Hughes. He was consuming so many tranquilizers that no one any longer kept an accurate count. But in one six-hour period, he took at least ten of his “Blue Bombers,” or ten-milligram Valium tablets—about forty times the recommended daily dose for someone his age. Not too surprisingly, then, he was sleeping more and watching fewer movies. On Saturday, March 17, the day of his appointment, Hughes started off at 3:15 A.M. by watching Madame Sin. He had an enema at 4 A.M. and spent the next nineteen hours in bed or in the bathroom.66 At 11:35 P.M. Mell Stewart arrived to trim his hair and beard and clean him up, and at 1:15 A.M. on Sunday morning O’Callaghan and Hannifin were shepherded into Hughes’s darkened bedroom, accompanied by two other men—Bill Gay, who had not been in Hughes’s presence since Hughes placed him in “isolation” in 1958, and Chester Davis, who had never before laid eyes on Hughes. While Gay and Davis sat quietly in the background, O’Callaghan and Hannifin talked for more than an hour with Hughes, who remained seated throughout, a blanket wrapped tightly around his otherwise naked body. The governor came away from the meeting greatly impressed. He told reporters that Hughes had a “commanding personality. There was no doubt in the meeting who was telling the people what to do. When he disagreed, his voice rose. He repeated statements when he wanted to stress a point.” The governor added that “there is every indication that some day he hopes to return to Nevada. It is very clear he likes the state. He has confidence in his holdings. He made the statement how he loves Nevada.”67

After fifteen years in total seclusion, Hughes had embarked on, for him, a whirlwind of social and business intercourse. In fifteen months he had conducted a long-distance telephone interview with half a dozen newsmen, a meeting with a Merrill Lynch executive and a Wall Street lawyer, a session with the president of Nicaragua and the American ambassador, and now a personal conversation with the governor of Nevada, the state’s gaming chief, his own lawyer, and even Bill Gay. What with all these person-to-person dealings after so many years of inactivity, perhaps it was time to fly once again.

With Hughes’s arrival in London, there had been another addition to his personal staff. Jack Real, the former Lockheed executive so close to Hughes in the late 1950s, who had acted as liaison between Lockheed and Hughes through most of the 1960s, moved into the Inn on the Park. Real had gone to work for Hughes in 1971, but he was not an aide. Indeed, his function was difficult to define. He was there because Hughes had asked for him, which made him the first staff member to join the inner circle without being groomed by Romaine Street. His presence in London annoyed Gay and certain of the aides, but little could be done except to isolate him as much as possible, allowing him into the bedroom only when Hughes demanded to see him.

And Hughes demanded fairly often. Real talked to him about airplanes and flying, just as he had done when Hughes was passing through his mental collapse in 1957 and 1958. With his interest quickened, Hughes picked up his aviation publications again, absorbing the advances in aircraft design and performance, and in the spring of 1973, after a thirteen-year absence from the cockpit, he announced that he was about to fly again. His staff was stunned. If Hughes began to venture forth, Romaine Street might lose control. They blamed Real. “It’s easier to take care of him when he is in bed,” one of the aides told Real. “Go home. You’re getting him alive.”68 The “aides got more and more upset and kept trying to get [Hughes] back into his chair,” but Hughes insisted he was going to fly, even if he did not have a valid pilot’s license.69

Real pushed ahead, negotiating for an aircraft through an old friend, Tony Blackman, the chief test pilot and a salesman for Hawker Siddeley. They reached agreement on the lease-purchase of a Hawker Siddeley 748, a twinengine turboprop similar in size to a DC-3. But there was a complication: Hughes wanted to test fly another 748, not the one he intended to buy. Hughes liked to keep the flying time on his aircraft to a minimum, Blackman recalled, “just like a fellow that goes and buys a tailor-made suit and never wears it, he keeps wearing the old suit.”70 Blackman finally secured a military demonstration aircraft for the test. The flight awaited Hughes’s pleasure. Unbeknownst to Blackman as he waited for two weeks, Hughes was drugged and unable to leave his bedroom. “He looked like he was in the outer spaces,” Real said.71

Then one day in May of 1973, Real and an aide drove Hughes to a hangar at Hatfield Airport, located on a huge farm just north of London. With Real on one side and the aide on the other, Hughes got out of the car and slowly walked around the aircraft. After he was introduced to Blackman, Hughes complained that the rivets on the fuselage were not flush with the body. Blackman explained there were flush rivets on the wing tops, where it mattered, and extended rivets on the fuselage for easier maintenance. Hughes, who had built the first flush-riveted airplane, still disapproved. When he got into the 748, Hughes inspected the cabin, entered the flight deck, and settled into the pilot’s seat. Blackman said nothing. He had been told by Real that Hughes would expect to sit in the pilot’s seat. Because the 748’s nose-wheel steering system was on the left-hand side, Blackman was somewhat uneasy. The 748 flight manual called for two pilots. Blackman was nonetheless confident he could fly the plane unassisted, if need be. Still seated, Hughes slipped off his light-blue shirt, unfastened his dark slacks, and dropped them down to his knees. Naked and grinning, Hughes gripped the controls. It was the natural reaction not of an exhibitionist, but of one who had been unaccustomed to clothing for more than a decade.

Warned about Hughes’s germ phobia, Blackman handed him a new radio headphone set still wrapped in cellophane. With Real and the aide back in the cabin and Hughes in the pilot’s seat, Blackman signaled the engineers to tow the plane out of the hangar. The engines were started and Hughes taxied the plane along a zigzag course to the end of the runway. The tower gave clearance, Blackman opened the throttles, and the 748 rolled down the runway and lifted off. For the first time in thirteen years, Howard Hughes was behind the controls of a plane in flight. Blackman unobtrusively acted as a flight instructor, handling the critical maneuvers and those that Hughes neglected. When Hughes experienced difficulty keeping the 748 on course, Blackman politely turned the aircraft in the direction he wanted. They were no sooner airborne, however, than Blackman discovered that Hughes wished only to do takeoffs and landings—take off, circle the field, touch down, and take off again. Black man had two concerns. He did not want to offend Hughes—he hoped to sell him some airplanes. Yet he wanted to stay alive. When they made the first passes at the field, Blackman, who controled the throttles throughout, kept the speed up and each time pulled up without touching down. “As we were approaching what I thought was certain disaster,” he said, “I would pull the stick back and we’d bow up.”72 When Blackman took exception to one landing—they nearly ran out of runway—Hughes observed that Blackman was not the first to criticize his landings. Late that night they finally returned the 748 to its hangar.

A second flight was arranged across the English Channel to Ostend, Belgium, and back. When Hughes, Real and an aide arrived at Hatfield Airport late one night in June, it was raining and visibility was poor. Blackman tried to persuade Hughes to cancel the flight, but Hughes insisted. Blackman reluctantly agreed, but asked a friend and copilot to accompany them. The flight plan called for a stop at Stansted Airport. By the time they reached the field, the weather was so bad that the ground lights were not visible beyond fifty feet from the runway. After landing, Blackman could barely find the taxi ramp. Blackman then turned to Hughes and told him that if he wanted to fly to Belgium, he would have to go back and sit in the cabin and allow his copilot to come up to the cockpit. As the rain pelted down on the plane, Real, Hughes, and Blackman argued. When Blackman declared there would be no flight unless Hughes left the cockpit, Hughes turned to Real and said, “Well, I can fly. Tell him to get off the thing.”73 Eventually, Real convinced Hughes to leave the cockpit and he went back into the cabin and lay down. Blackman and his copilot placed the 748 on automatic pilot, flew to Ostend, turned around, and returned to Stansted.

A third flight followed in July, this time in a de Havilland 125, a twin-jet executive aircraft in which Hughes felt more comfortable. He told Blackman that the de Havilland made the 748 feel like a truck. Each time they flew, Real sent a report to Romaine Street to be included in the records that accounted for every minute Hughes spent in a plane. Real advised Romaine Street following the flight that “On July 17, HRH took off from Hatfield Airport at 1828 and landed at 2015 (he made seven takeoffs and landings at Stansted Airport). The airplane was a DH 125-400, License No. G-AYOJ.”74

Their fourth flight late in July, again in the De Havilland, was to Woodford, northeast of London, where Blackman’s club was located. As in the previous flights, Blackman backed up Hughes at the controls. But this time, despite his obvious frailty, Hughes appeared more alert than on earlier outings. When they taxied along the runway, Blackman pointed out his lodge near the landing strip. Hughes, who had given Blackman the impression that he was tired of living in hotel rooms, said he would like to visit the lodge for a few weeks. Blackman thought it could be arranged. It certainly would be more convenient, for Hughes would be living right next to his plane. After their flight that day, Blackman took Hughes to see a mock-up of a new Hawker Siddeley aircraft. Chuck Waldron, the aide who accompanied Real and Hughes on the flight, recalled that Hughes spent some time inspecting it. “He walked up the steps into the mock-up and through the airplane and back down, around the building; checked all the different parts of that big hangar where they had their mock-up.”75 Mentally, Hughes was in fine form. It was, said Real, “the best day in the four years that I’d spent with him.”76

But on August 9, Hughes’s flying days came to an abrupt end, and with them any hope of moving from his hotel room to Blackman’s lodge at Woodford or anywhere else. Exactly what happened that day is unclear, but somehow Hughes fell in his bedroom and fractured a hip. The aides later offered conflicting versions, but all said that no one was with Hughes at the time. Eckersley said Hughes “got up and went to the bathroom in the night and just tripped on a rug. There wasn’t anything to trip on. He just fell down and hurt himself.”77 Francom said, “he got up to go to the bathroom and he was still in a semi-sleeping condition, and he reached for the bathroom door to open it and missed it or something and lost his balance. I think there was a sideboard or table near the door, and I think he hit his hip on that when he fell back.”78 Waldron said, “he was coming out of the bathroom and made a quick turn to turn the light off or something and popped his hip and fell down.”79

The first non-Hughes doctors to examine the industrialist since he left Las Vegas were dismayed at his physical condition. Dr. William Young, a London radiologist, visited Hughes in his Inn on the Park bedroom on August 11 to take X-rays. When he arrived, Dr. Young said, “I observed Mr. Hughes naked in a dimly lighted room, lying on a bed and covered with paper toweling. I observed Mr. Hughes’ skin to have a parchment-like quality. Mr. Hughes had long toenails and fingernails resembling that of a Chinese mandarin. Mr. Hughes was quite emaciated. In positioning Mr. Hughes for X-ray, we were instructed to keep paper toweling between Mr. Hughes, our hands and the X-ray plates, because we were told Mr. Hughes was concerned about germs.” Dr. Young, who had seen Japanese prison camps during the Second World War, likened Hughes’s malnourished condition to that of prisoners he had examined then.80

At first the aides attempted to persuade Dr. Walter C. Robinson, a prominent orthopedic surgeon, to perform the operation in Hughes’s bedroom. When Dr. Robinson refused, Hughes was finally admitted to the London Clinic on August 12. Dr. E. Freeman Johnson, the anesthesiologist, described Hughes as “extremely emaciated, to an extent which would have taken some months at least to have developed. Mr. Hughes appeared to be much older than his 67 years of age and, in my opinion, Mr. Hughes would have found it very difficult to have done anything more than simply walk, even had his hip not been broken.” While administering the anesthetic, Dr. Johnson said he became quite concerned about the “very poor state” of Hughes’s teeth—many of which were loose—fearing that “during the surgery one of [the] teeth might break loose and be aspirated into Mr. Hughes’ lung.”81 Dr. Robinson affirmed the views of his colleagues, saying that prior to surgery he found Hughes “extremely emaciated and dehydrated.”82

Dr. Robinson inserted a steel pin in Hughes’s left hip. The operation was an unqualified success and Hughes should have been up and walking within a few weeks. Instead, when he returned to his darkened bedroom at the Inn on the Park, he crawled back into bed and never left it again without assistance.

That December, in Dayton, Ohio, Hughes was inducted into the Aviation Hall of Fame, joining fifty-two other pioneers of the air who had been similarlycited, including Orville and Wilbur Wright, Edward V. Rickenbacker, William Mitchell, Henry (Hap) Arnold, Charles A. Lindbergh, Wiley Post, and Jacqueline Cochran Odlum. Hughes, naturally, was not present for the ceremony, but he was represented by Edward Lund, the flight engineer and only other surviving member of his 1938 around-the-world flight crew. Lieutenant General Ira C. Eaker, another member of the Hall of Fame and a former Hughes Tool Company executive, spoke briefly, calling Hughes “a modest, retiring, lonely genius, often misunderstood, sometimes misrepresented and libeled by malicious associates and greedy little men.”83