I've gotten a lot of expert advice over the years. Lots of it has been valuable. Lots of it has been reasonable but completely contradictory to the other advice. It's a wry old bit of humor that you get three beekeepers in a room and you'll get four different points of view on almost any issue. I learned that early. I'm a researcher by trade and temperament, so I don't mind cracking books, asking questions, reading websites. In most cases, you start seeing where the advice overlaps and where it doesn't. There's some actual research, but most of the knowledge of any beekeeper, myself included, is a mix of received wisdom, observation, anecdotal conclusions, half-baked theories, and unproven certainties.

At first, as a beginner, I was looking for the “one right way” to handle bees. By the second or third book, though, the conflicts started causing me a lot of anxiety as I tried to make them into a coherent whole that I could follow. From there came the disillusionment of trying to determine whether any of the authors really knew what they were talking about. I began despairing slightly about whether I'd ever be able to master this.

At some point, though, the conflicts among experts freed me. Getting stuck eventually led to a conclusion: “Maybe there isn't just one way that works.”

I began tallying the things the authors all agreed about. For the short term, at least, I'd accept these things as probably true. Where they disagreed was where I was free to think, experiment, and figure out what seemed to make the most sense, but even some of that I discarded. For example, I had hoped that bees could be raised naturally, organically, without using a bunch of chemicals to keep them healthy. The books weren't promising. Each had a chapter about serious bee diseases and the chemicals that should be used to treat them. Eventually, through experience and seeking out new information, I found that it was possible to raise bees without that stuff.

I learned that there was an awful lot that could be learned from books, but that it wasn't enough. I, so analytically focused on problem-solving, had to stop, listen, watch, and learn from the bees themselves. I can't train them to do their jobs, but they've done a fairly good job of training me to do mine.

Having grown up in Michigan, I knew all about the football rivalry with Ohio colleges, so I got used to hearing Ohio Buckeyes being regularly disparaged. I was surprised, though, to be among Californian beekeepers who likewise badmouthed those “damned buckeyes.”

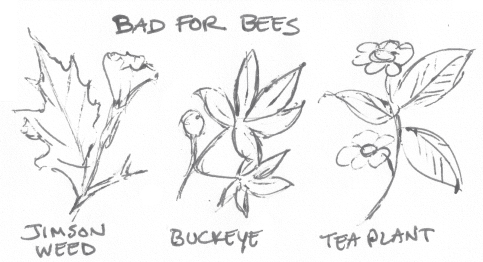

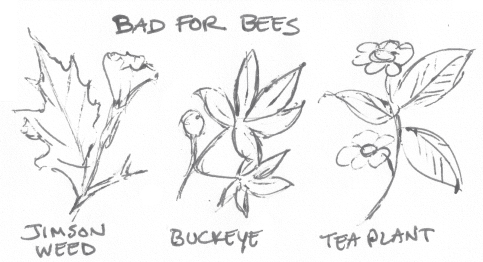

It turned out, though, that they weren't talking about football teams, or even Ohioans—they were talking trash about buckeye trees. It turns out that some buckeye trees can poison bees and destroy colonies. Buckeye pollen can cause developmental defects, resulting in larvae developing into adults without wings. If enough bees in a colony develop that way, the damaged bees can't forage, and the colony starves to death.

The good news is that bees prefer the pollen from other plants if they can find it, and only collect from buckeyes if it's all there is. The bad news is that a number of other plants are also poisonous to bees, including azalea, jimsonweed, plume poppy, and the tea plant.