DEVILS AND EUROPEANS, 1803–1933

The devil stories I was told as a farm boy were shot through with menace. Devils were as dangerous as the name suggested. In large packs they stalked and harassed pregnant, sick or dying cows and horses. If the stricken animal refused to fall the pack leaders would bite clean through its front legs and the rest would swoop in . . . I can see now that the old men and women who said they knew for a fact that devils attacked animals many times their size were just trying to protect me from the dangers of the bush. But they were also voicing the fears they had inherited from those early convicts who were being literal when they named the carnivores they had newly encountered after the Prince of Darkness.

RODNEY CROOME, HOBART

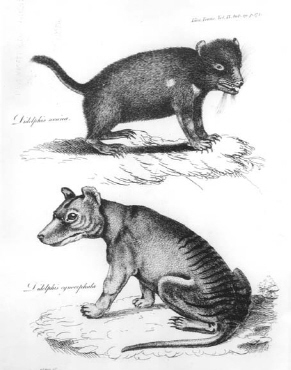

In 1803 an attempt to establish a convict colony at Port Phillip Bay (subsequently Melbourne) proved unsuccessful and led instead to the settlement of the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land. A member of the small founding group was George Prideaux Harris who, in Hobart Town, worked as a lawyer, journalist, surveyor and natural historian. He became the first European to describe and classify the devil, naming the squat, peculiar little animal Didelphis ursina. The name he gave the genus echoes the American opossum, while the species name was intended to reflect its bearlike (ursine) qualities, not least the small round ears. Harris correctly noted a number of similarities between the devil and the thylacine, one being a marsupial trademark, that the rear heels of both are long and callous.

George Prideaux Harris, after whom the devil is named, wrote the first description of the animal in 1806:

These animals were very common on our first settling at Hobart Town, and were particularly destructive to poultry, &c. They, however, furnished the convicts with a fresh meal, and the taste was said to be not unlike veal. As the settlement increased, and the ground became cleared, they were driven from their haunts near the town to the deeper recesses of forests yet explored. They are, however, easily procured by setting a trap in the most unfrequented parts of the woods, baited with raw flesh, all kinds of which they eat indiscriminately and voraciously; they also, it is probable, prey on dead fish, blubber, &c. as their tracks are frequently found on the sands of the sea shore.

In a state of confinement, they appear to be untameably [sic] savage; biting severely, and uttering at the same time a low yelling growl. A male and female, which I kept for a couple of months chained together in an empty cask, were continually fighting; their quarrels began as soon as it was dark (as they slept all day), and continued throughout the night almost without intermission, accompanied with a kind of hollow barking, not unlike a dog, and sometimes a sudden kind of snorting, as if the breath was retained a considerable time, and then suddenly expelled. The female generally conquered. They frequently sat on their hind parts, and used their fore paws to convey food to their mouths. The muscles of their jaws were very strong, as they cracked the largest bones with ease asunder; and many of their actions, as well as their gait, strikingly resembled those of the bear . . . Its vulgar name is the Native Devil.1

George Prideaux Harris, the deputy Surveyor General in the first party of Britons to settle Van Diemen’s Land, drew these devil and thylacine sketches for the Linnean Society of London in 1806. (Courtesy Linnean Society of London)

Fifty years after Harris wrote his description of the devil, the English naturalist and artist John Gould compiled his three-volume Mammals of Australia and his seven-volume Birds of Australia, both brilliant and enduring records. Gould, who predicted the thylacine’s demise nearly a century before its extinction, wrote of the Tasmanian devil:

[I]ts black colouring and unsightly appearance obtained for it the trivial names of Devil and Native Devil. It has now become so scarce in all the cultivated districts, that it is rarely if ever, seen there in a state of nature; there are yet, however, large districts in Van Diemen’s Land untrodden by man; and such localities, particularly the rocky gullies and vast forests on the western side of the island, afford it a secure retreat. During my visit to the continent of Australia I met with no evidence that the animal is to be found in any of its colonies, consequently Tasmania alone must be regarded as its native habitat.

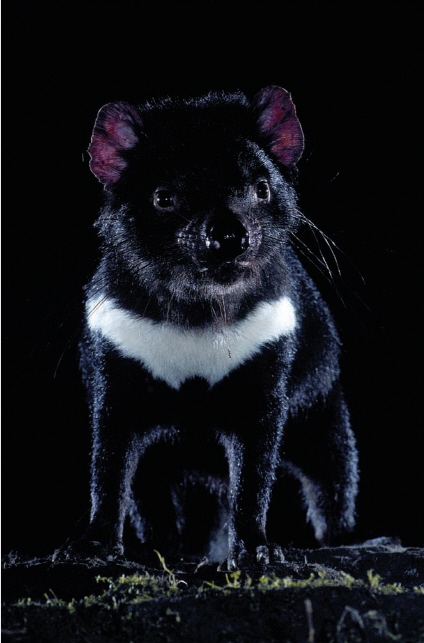

Famous naturalist John Gould described many species of Australian fauna in the mid-nineteenth century and had an array of artists working for him, including Henry Richter who drew this devil from a live specimen in London’s Zoological Society menagerie. Unusually for a Gould work of art, it’s anatomically incorrect, having a small, underslung jaw. (Courtesy David Owen)

In its disposition it is untameable and savage in the extreme, and is not only destructive to the smaller kangaroos and other native quadrupeds, but assails the sheep-folds and hen-roosts whenever an opportunity occurs for its entering upon its destructive errand.

Although the animal has been well known for so many years, little or nothing more has been recorded respecting it than that which appeared in the ninth volume of the Linnean Society’s Transaction from the pen of Mr Harris . . .2

Writing in 1880, author and artist Louisa Anne Meredith did much to publicise the new British colony. Her books were very popular in England and her chatty, hotchpotch style says as much about Victorian readers as it does the animal under scrutiny:

[I]f anyone desires to see a blacker, uglier, more savage, and more untameable beast than our ‘Devil’, he must be difficult to please—that’s my opinion. I suppose those who bestowed such a name on him had pretty good reasons for it, and knew that they only gave the devil his due . . . I’ve heard people say in joke, of others who had very wide mouths, that, when they gaped, their heads were off; but it seems true of this animal, his jaws open to such an extent, and a murderous set of fangs they show when they do open!

The head, which is flat, broad, very ugly, and with little skull-room for brains, takes up one-third the whole length of the beast, which is usually from a foot and a-half to two feet, some being larger. The tail sticks stiffly out, as if made of wood, the feet are something like a dog’s, only more sprawly, and with very big claws. It is an awkward beast, and cannot go much of a pace at the fastest. On fairish ground, a man can easily run one down.

One day I was out with Papa in the back-run, and we found a devil. I started full tilt after him, and came two or three good croppers amongst the rocks to begin with, but I held on, till all of a sudden he stopped short—I couldn’t, so I jumped right over him. He gave a vicious snap at my legs with his big jaws, but, luckily for me, he was a second too late. I turned and knocked him over, and papa came up and finished him— finished killing him, I mean. We don’t show the brutes any mercy; they do too much mischief. The young lambs stand no chance at all with them. So we hunt them down, or set traps, or dig pitfalls—any and every way we can destroy them we do. Why, one winter, some years ago, one of Papa’s shepherds caught nearly one hundred and fifty! They seem to go about in families or parties; for when you catch one, you are tolerably certain of getting six or seven more, one after another, and then perhaps you will not hear of any for a good while. Of course they are much scarcer than formerly, and a very lucky thing, too.

I don’t think I mentioned the fur—but it is not fur, it’s longish, very coarse, black hair, almost like horse-hair; and then as to fleas, they swarm! One of the men brought a dead one to the house one day for Mamma, and it was laid in the garden. Mamma and Lina were soon down on their knees beside it, peeping at its eyes and teeth and ears and all the rest of it; when Lina said, ‘Oh, look; how very curious! There are small, brown scales, like a coat of mail, all over it, under the hair’. Mamma looked where Lina had parted the long hair, and didn’t she jump! Lina’s coat of mail was just a coat of fleas. The post-mortem examination was cut very short, I assure you, the ‘subject’ summarily disposed of, and two or three buckets of water poured on the place where it had lain. A pleasant kind of thing for a pet!

There are two sorts of devils—one is all black, the other has a white tail-tip and a white mark like a cross down the throat and between the fore-legs; but one is just as hideous as the other. I believe you cannot tame them, and I am very sure I shall never try. People who have made the attempt say they are as stupid as they are ferocious, and never seem to know one person more than another, but growl and bite at all alike.3

For all her apparently direct association with devils, many of her descriptions are clearly inaccurate, and it’s of interest that the drawing of the animal accompanying Meredith’s text is a freehand copy of Gould’s original, unattributed and minus the background devils. She—or another—likewise copied the famous Gould lithograph of a thylacine pair, an animal admittedly much harder to locate, let alone sketch.

Louisa Anne Meredith died in 1895. In that year, wealthy Hobart socialite Mary Roberts opened a private zoo at Beaumaris House, close to the town. The contrast between the women is stark. Not only did Mary Roberts like devils, she bred them, and in doing so helped shift its image from diabolical and satanic to merely animal. Roberts achieved international fame for her devotion to animal causes, through activities such as her founding of the Anti-Plumage League. But she also had a highly developed business sense, importing wildlife from all over the world, while exporting whatever Tasmanian fauna she could.

Not unlike George Harris almost a century earlier, in 1915 Mary Roberts wrote about the devil for an academic British audience, this time for the London Zoological Society. It’s an important and accurate document, given the lack of written information about the devil then and universal ignorance of it. The article is titled ‘The Keeping and Breeding of Tasmanian Devils’:

Bipedal young devil and wolverine—the similarities in these unrelated mammals are striking. (Wolverine: Daniel J. Cox, Natural Exposures Inc. Tasmanian devil: The Mercury)

Bipedal young devil and wolverine—the similarities in these unrelated mammals are striking. (Wolverine: Daniel J. Cox, Natural Exposures Inc. Tasmanian devil: The Mercury)

Opposite page: A young adult devil. This backlit photograph was taken in the wild.

Opposite page: A young adult devil. This backlit photograph was taken in the wild.

(Christo Baars) This page: A pair of adults establish the feeding hierarchy at a food site.(Christo Baars) Feeding devils assess the approach of a newcomer. (Nick Mooney)

(Christo Baars) This page: A pair of adults establish the feeding hierarchy at a food site.(Christo Baars) Feeding devils assess the approach of a newcomer. (Nick Mooney)

King’s Run. On the isolated coast of north-west Tasmania, this small shack—Geoff King’s ‘devil restaurant’—has played host to devil watchers from all over the world. Devils are attracted to a staked out, spotlit wallaby carcass.(Tim Dub)

King’s Run. On the isolated coast of north-west Tasmania, this small shack—Geoff King’s ‘devil restaurant’—has played host to devil watchers from all over the world. Devils are attracted to a staked out, spotlit wallaby carcass.(Tim Dub)

King’s Run. On the isolated coast of north-west Tasmania, this small shack—Geoff King’s ‘devil restaurant’—has played host to devil

watchers from all over the world. Devils are attracted to a staked out, spotlit wallaby carcass. (Tim Dub)

King’s Run. On the isolated coast of north-west Tasmania, this small shack—Geoff King’s ‘devil restaurant’—has played host to devil

watchers from all over the world. Devils are attracted to a staked out, spotlit wallaby carcass. (Tim Dub)

Ollie and Donny. Donny and Clyde were orphans raised at the home of David Pemberton, his partner Rosemary Gales and their children Sam, Elsa and Ollie. (David Pemberton)

Ollie and Donny. Donny and Clyde were orphans raised at the home of David Pemberton, his partner Rosemary Gales and their children Sam, Elsa and Ollie. (David Pemberton)

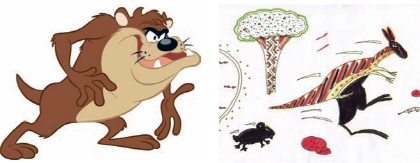

Taz, the indomitable Warner Bros. character. Just five Taz cartoons were made between 1954 and 1964. He was resurrected in 1990 and became a billion-dollar income generator for Warner Bros. (Courtesy Warner Bros. Taz, Tasmanian Devil and all related characters and elements are trademarks of and © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.)

Taz, the indomitable Warner Bros. character. Just five Taz cartoons were made between 1954 and 1964. He was resurrected in 1990 and became a billion-dollar income generator for Warner Bros. (Courtesy Warner Bros. Taz, Tasmanian Devil and all related characters and elements are trademarks of and © Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.)

Aboriginal students at Rokeby Primary School in southern Tasmania wrote and illustrated a Tasmanian devil story in the tradition of Dreamtime legends.

Aboriginal students at Rokeby Primary School in southern Tasmania wrote and illustrated a Tasmanian devil story in the tradition of Dreamtime legends.

(Courtesy Grant Williams, Rokeby Primary School)

Devil Facial Tumour Disease is a virulent cancer of unknown origin and with no known cure. First detected in 1996, it has spread across most of the island, greatly reducing the devil population in some areas and threatening the survival of the species. (Nick Mooney)

Devil Facial Tumour Disease is a virulent cancer of unknown origin and with no known cure. First detected in 1996, it has spread across most of the island, greatly reducing the devil population in some areas and threatening the survival of the species. (Nick Mooney)

Albino devils are extremely rare. This photograph of one crossing a road was taken near Marrawah. (Geoff King)

Albino devils are extremely rare. This photograph of one crossing a road was taken near Marrawah. (Geoff King)

This devil, named Coolah, lived at Fort Wayne Chidren’s Zoo in northern Indiana, United States. He had the distinction of being probably the world’s oldest captive devil, living for seven and a half years, and was the last known captive devil outside Australia. (Courtesy Elaine Kirchner, Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo)

This devil, named Coolah, lived at Fort Wayne Chidren’s Zoo in northern Indiana, United States. He had the distinction of being probably the world’s oldest captive devil, living for seven and a half years, and was the last known captive devil outside Australia. (Courtesy Elaine Kirchner, Fort Wayne Children’s Zoo)

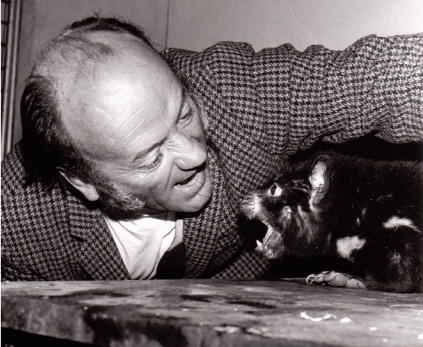

Eric Guiler initiated modern research into the Tasmanian devil; he is seen here enticing a devil to ‘sing’. He also devoted much of his career to searching for the thylacine.

Eric Guiler initiated modern research into the Tasmanian devil; he is seen here enticing a devil to ‘sing’. He also devoted much of his career to searching for the thylacine.

(Courtesy The Mercury)

A devil den and latrine site at the base of a sandstone cliff at Fentonbery. High quality dens such as this probably remain in use for hundreds of years. (Courtesy Billie Lazenby)

A devil den and latrine site at the base of a sandstone cliff at Fentonbery. High quality dens such as this probably remain in use for hundreds of years. (Courtesy Billie Lazenby)

Until I was asked by Mr. A. S. Le Souëf, Director of the Zoological Gardens, Moore Park, New South Wales, early in 1910 to obtain, if possible, Tasmanian Tigers (Thylacinus cynocephalus) and Devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) for the London Zoological Society, I had never thought of keeping either of these animals in my collection; in fact, they were quite unknown to me except as museum specimens, although I had frequently visited remote parts of our island. I have vivid recollections, however, of how, when a young girl at boarding-school in the late [eighteen] forties, some of the girls from Bothwell, near the Lake District, used to give graphic and terrifying accounts of the Tasmanian Devils with their double row of teeth. This belief is not yet exploded, as it was impressed upon me lately with the utmost confidence by a country visitor that such was the case; he not only believed, but said ‘he had seen’. The teeth have been described to me by a scientist as truncated.

Shortly after hearing from Mr. Le Souëf, by means of advertising, writing, etc. I obtained three for the London Society, and having then become thoroughly interested I determined to keep some myself. Since that time a large number have passed through my hands, and more than once I have been ‘a woman possessed of seven devils’.

In April 1911 I received a family (a mother and four young), and again in September of the same year a similar lot arrived. The former were very young, and I had the opportunity of watching their growth almost from their first appearance when partly protruding from the pouch. When sending them, the trapper wrote that ‘the mother was so quiet, I need not be afraid to pick her up in my arms’. The little ones hung from her pouch (heads hidden in it), and she lay still and motionless as if afraid of hurting them by moving, and allowed me to stroke her head with my hand. However timid they may be, and undoubtedly they are extremely so, growling and showing their teeth when frightened, they always evince this gentleness and stillness when nursing little ones.

Mary Roberts owned and operated Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart between 1895 and her death in 1921. She collected animals and birds from all over the world and also maintained a thriving business exporting Australian fauna. She wrote that Tasmanian devils were her favourite creatures. Her insights into their behaviour were in marked contrast to public perceptions of them as stinking vermin. (Courtesy Collection Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery)

The skin of the young, on arrival, had the appearance of a slate-coloured kid glove, the tail darker towards the tip. The hair could be seen growing black and velvety from the head downwards, the latter being hidden in the pouch for some days, and it was interesting to note the progress of the growth of the hair from day to day. The shoulders were covered while the hindquarters were almost, or quite, bare, although a faint streak of white was discernible where the white markings were to come later on. At this early stage, should the mother get up to move about, which she rarely does in the daytime, the young somehow scramble into the pouch again.

This family went later to the London Society, but the second, which came on the 16th of September, I kept for my own pleasure, with the exception of the mother; as she had lost a foot when being trapped, I thought it best to have her destroyed later on. Unfortunately, when they were about half grown one escaped into the garden, and the next morning her mutilated remains were found—she had fallen a victim to our two fox-terriers. The three survivors have been ever since an unfailing source of interest and amusement to my family, to visitors, and myself. When a bone or piece of meat was thrown to them a tug-of-war was always the result, and sometimes a chase into one door and out of the other of the little cave. At other times, while one has been holding on to a bone held in my hand, I have lifted it completely off the ground, while another would cling on round the waist and try to pull it down.

Many visitors from the Commonwealth have heard such exaggerated accounts of the ferocity and ugliness of the Tasmanian Devil (others, again, have believed it to be a myth), that they sometimes express surprise when they see them so lively, sprightly and excited, running out to my call; they then remark, ‘the devil is not so black as he is painted’.

Two of these Devils were latterly kept together as a pair, and for the purposes of this article I will call them Billy and Truganini, after the last two survivors of our lost Tasmanian race.4 These showed no disposition to breed until April 1913, and my observation of them and of many others that I have had in my keeping is, that the disinclination to take up maternal duties is always on the part of the female. I then noticed suddenly a decided change—that Billy would not allow her to come out of their little den; if she did venture when called to be fed, or at other times, he immediately attacked her and would drag her back by the ear, or any other part, but although otherwise cruel, he would carry food in to her. When I called her, it was pitiable to hear her whining; but it was of no avail, for Billy was a relentless tyrant and kept her in strict seclusion for quite ten or twelve days; then early in May he allowed her to be free once more. From thence onward, although they were sometimes peaceable and affectionate, the balance of power was completely on Truganini’s side; she constantly resented his approach by biting and snarling at him: it seemed as if coming events cast their shadows before, and she instinctively felt that he would do the young some injury. From now her pouch was anxiously scanned day by day, but it was some time before I could be sure that it was gradually enlarging. I had been advised by Dr Hornaday, of the New York Zoological Park, that if ever the Tigers or Devils were likely to have young, to remove the male, and as soon as I was certain, I had Billy taken away and placed with the other member of the family. This made Truganini most unhappy, as he was near enough for her to hear him, besides which, the two males fought; so, being cautioned by my family that perhaps my interference might cause a disaster, I yielded and replaced him, doing so with many misgivings. Matters went on much the same until late in September, when to my delight a tail, and at other times part of a small body, could be seen sticking out of the pouch, more especially when she sat up to wash her face, or rolled upon her back; unlike domestic cats, the devils use both paws for washing, placing them together and thus making a cup-like depression which, when thoroughly licked, is rubbed well over the face. Everything looked very promising on the Sunday before Michaelmas Day, when I noticed Truganini carrying large bunches of straw about in her mouth, evidently seeking for a retired place to make a bed, and we had already placed some fern logs in a corner of their yard. As Billy would follow her about and interfere, I had a box put down with a hole cut in the side that she might hide under; but it was of no use, as where she went he would also go, and a scrimmage was the inevitable result. Early next morning, with many misgivings I left home for ten days, only to find on my return that her pouch was empty and that the young had disappeared, and as no remains whatever had been found, I could only conclude that they had been eaten by Billy.

Tasmanian devils at Beaumaris Zoo, c. 1910. (Courtesy Collection Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery)

Thus ended all my hopes and anticipations for 1913. I have not so far related an incident that took place just before the breeding-season. Being hopeful that Truganini might have young in her pouch, and my assistant being as usual very busy, Professor T. T. Flynn, of the Tasmanian University, who is always interested in our marsupials, kindly offered to examine her pouch. As soon as an attempt was made to catch her, Billy grasped the position of affairs and fought to defend her with all his might, even getting behind her in the little cave, putting a paw on each shoulder and holding her tightly, lest she might get into what appeared to him to be the danger zone. By dint of perseverance and a little strategy he was outwitted at last, but our hopes were doomed to disappointment.

Truganini has now passed through another period of retirement, and I am hoping to record shortly a greater measure of success for 1914.

I cannot close this article without a few words in defence of the Tasmanian Devil, as I am sure that it is more or less ‘misunderstood’, and the article with photograph published in the ‘Royal Magazine’ for October 1913 under the name of L. R. Brightwell, F. Z. S., is, I consider, greatly exaggerated both as regards their appearance and character, viz., ‘They are well named, for they tear everything, even sheep, to pieces if they get the chance’.

On several occasions when one of mine has escaped, the only mischief done has been the destruction of a fowl or a duck or two. It would have been just as easy for a wallaby to have been killed if they had had the inclination, about which our fox-terriers would not have hesitated for a minute if a chance had occurred. When in transit to London last year one escaped, and I have been told by the chief officer of the vessel that ‘the passengers were much alarmed as there were children on board, and someone went about with a revolver’. Later I came across the butcher who was in charge at the time, and he appeared to have been rather amused than otherwise, and told me the missing one was discovered at last sleeping under the berth of one of the sailors! I don’t wonder, with the reputation that the devils have, that the passengers were alarmed.5

Mary Roberts had more luck in 1914 when Truganini gave birth to three babies. Billy was again the father but was now kept away from the maternal enclosure. Roberts compiled diary notes, as with these examples:

29th—All three playing like puppies, biting each other and pulling one another about by the ears . . .

30th—Whole family hanging from the mother as she ran out, and one hardly knows which to admire most, her patience and endurance, or the hardihood of the young in holding on and submitting to so much knocking about. The whole process seems very casual and most remarkable . . . The baby devils had the sense of smell very strongly developed; immediately I approached, their nostrils would begin to work and a vigorous sniffing would go on. They were also expert climbers, and although I had some specially constructed yards made, they would get up the wire-netting and walk along the top rail quite easily; at other times they would climb a pear-tree growing in their enclosure and sit in the branches like cats.6

Her article concludes with a section headed ‘General Remarks’:

I have always found devils rather fond of a bath; quite recently, going down to their yard after an illness and finding only a drinking vessel, I ordered a larger one to be put in, and they showed their pleasure by going in at once, sometimes two at a time. I have occasionally poured water from a can over them, when they would run to and fro under it with much enjoyment.

Their sight in daylight is rather defective; they seem to pick up their food more readily by smelling than by seeing, and I think they can see objects better at a distance.

At the present time I have six running together, my own three and three that I bought when in their mother’s pouch. All are tame, frolicsome, and lively. I can go in and have a bit of fun with them, and when I am outside their enclosure they frequently climb the wire-netting to the height of nearly six feet, and get their little black faces close to mine with evident delight. We have tried more than once to get them photographed, but it is impossible to keep them quiet, they are on for a scamper all the time. Recently an adult escaped, and it was discovered by a passing school-boy sitting on a high fence bordering the street, under the shade of some elm-trees, many people passing on the foot-path without observing it. They are, however, always very timid when coming down.

They are fond of the sun, and look well when basking in it, the rays shining through make their ears appear a bright red, fore-feet parallel with the head, hind-quarters quite flat on the ground and turned out at right angles, somewhat as a frog.

My sympathy with my little black ‘brothers and sisters’ is intense, probably evoked by having suffered much mentally owing to the gross cruelties which have come under my notice, the result of capturing them in traps. Frequently three or four have been sent to me in a crate, only to find later on one with a foot shot off or a broken leg. In a consignment received some time ago, a dead one was found; it bore unmistakable signs of a snare previously, round the neck, one foot was gone (an old injury), and finally a recently smashed leg much swollen, the cause of death. I communicated with the S.P.C.A., and since then have had none from that district.

I have derived much pleasure from studying the habits and disposition of the Tasmanian Devils, and have found that they respond to kindness, and certainly show affection and pleasure when I approach them. I have been led to believe that no case of their breeding in captivity has been recorded, and certainly not in Tasmania.

Others who do not know or understand them may think of them as they like, but I, who love them, and have had considerable experience in keeping most of our marsupials, from the Thylacine down to the Opossum Mouse (Dromica nana), will always regard them as first favourites, my little black playmates.7

Mary Roberts wasn’t a trained scientist. But her Beaumaris Zoo not only popularised native animals until then considered loathsome, dangerous and expendable; it also attracted those few scientists who had begun devoting their energies to understanding and protecting the island’s fauna. One was Clive Lord, Director of the Tasmanian Museum, who in 1918 compiled a list of about 50 known descriptions, classifications and drawings of the devil. He expressed concern that native species such as the devil were decreasing in numbers while very little was known about them.

Another was Professor T. T. (Theodore Thomson) Flynn, who occupies an important place in Australian zoology as a pioneering twentieth-century mammalogist. His works on the embryology and early development of native animals are rightly described as classics. In 1909 he had become the inaugural Professor of Biology at the University of Tasmania and for 20 years remained devoted to his research.

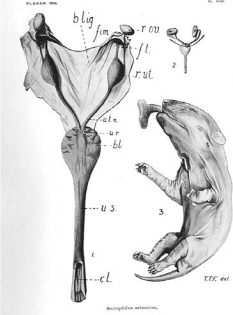

Professor T.T. (Theodore) Flynn, a biology lecturer and researcher at the University of Tasmania from 1909 to 1930, was the father of actor Errol Flynn. Theodore undertook pioneering laboratory work on devils, one result being this fine natural history illustration of the urogenital system and pup on teat. (Courtesy Collection Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery)

One of Flynn’s early publications was ‘Contributions to a Knowledge of the Anatomy and Development of the Marsupiala: No. I. The Genitalia of Sarcophilus satanicus’. His research derived from a single female devil, the first ever to come into his possession—not from Beaumaris Zoo but from Clive Lord. In his introduction Flynn noted that his intention had been to study a number of specimens before publishing his results, but their ‘increased scarcity’ decided him otherwise.8

The research itself was obviously not easy, Flynn noting the ‘unfortunate lack of original communications and papers in Tasmania’.9 His introductory notes are illuminating:

The specimen of Sarcophilus satanicus, of whose genital organs this communication is a description, was forwarded to me through the kind offices of Mr J. E. C. Lord . . . This is the only female which I have as yet obtained and I had originally intended that its description should wait until further specimens had come to hand; the increased scarcity, however, of these animals, together with the discovery of a number of interesting and significant points in the morphology of the genital organs, has influenced me to publish the results earlier than otherwise would have been the case. Portions of the paper can as yet be regarded only as preliminary notes. This is due, in the first place, to scarcity of material, and, in the second, to an unfortunate lack of original communications and papers in Tasmania.

His short, preparatory description further reveals the difficulties of conducting pioneering scientific work under the conditions he experienced:

The specimen was a full-grown female, with three fairly advanced young in the pouch. All had been dead for two days. The pouch-young were fixed entire in corrosive-sublimate-acetic-solution, the genital organs of the mother in picro-sulphuric solution. In this latter case, on sectioning, it was found that what blood there was in the vessels had hardened so much, that it was only with extreme care and difficulty that sections could be cut at all. The hopeless gapping of the razor-edge, with consequent damage to the sections, is well indicated in Fig. 10.10

Guiler provides an interesting snapshot of Flynn and Roberts:

Flynn was a very powerful personality and full of drive and energy which led him into many adventures, creditable and otherwise. He was often at the Zoo in his early days in Tasmania but the [Roberts] Diary entries show a declining enthusiasm and in August 1918 Mrs Roberts records that she had sent an account to Prof. Flynn for the devils, adding that she expected to be paid. In October 1918 she records that she rang the University ‘re the skeletons Flynn has’; he was to ring back the next day but did not do so. Possibly the non-payment for specimens may have been the cause of Mrs Roberts’ annoyance with Flynn but it is not surprising that there was a cooling in their friendship, as Mrs Roberts was most fastidious in all her dealings and Flynn most casual and unbusiness-like in his.11

Among Flynn’s ‘adventures’ were rumoured clandestine sales of thylacines. His family life was messy, including estrangement from his wife and considerable difficulty in managing his headstrong, wild, sexually charged son Errol, destined to become the dashing star of more than 50 Hollywood movies. The first chapter of Errol Flynn’s autobiography is called ‘Tasmanian Devil, 1909–1927’, and it was his Hollywood studio, Warner Bros., that created the irrepressible Looney Tunes cartoon character, Taz the Tasmanian Devil.

Tasmanian Museum director Clive Lord, in his own writings on the devil, observed:

Its hardy nature both in captivity and in its wild state cause one to wonder how it came about that this species became extinct on the mainland within comparatively recent times . . . In the rougher sections [of Tasmania] this species exists in fair numbers and there is every prospect of it remaining an inhabitant of such places for years to come.12

Lord also sounded what might be called an optimistic warning, one that has still not been resolved 200 years after George Prideaux Harris wrote his description of the devil. Towards the end of his life Lord wrote: ‘We, as Australians, have been placed in charge of a wonderful heritage, and it rests with us to respond to the trusteeship which has been granted us.’13

Clive Lord died in 1933 and so did official interest in the devil.