Late into the night with our little boat anchored just outside the weedline about thirty metres from shore we heard an ungodly commotion. Spotlight quickly activated to find a Tasmanian devil tearing open the tightly wrapped package of sandwiches which it had somehow managed to get out of an airtight lunch box. In the couple of minutes it took to start the outboard motor and push the boat through the weeds to shore the devil and complete contents of the lunch box were gone. The devil had obviously eaten in silence until it got to the sandwiches. It must have got frustrated with the plastic wrap hence the sudden noisy outburst.

BRIAN GEORGE, SORELL

Long ago, in the Dreamtime, deep in the Tasmanian bush, Wing-go-wing the Tasmanian devil finished eating her dinner. She didn’t, though, have a full stomach and was still hungry. She started hunting again and spied a kangaroo. ‘This would taste just right and fill up the hollow in my stomach,’ she said. Ooroo, the kangaroo, didn’t see Wing-go-wing approaching . . . creeping . . . unseen. Wing-go-wing chased after Ooroo, snapping at its legs. He bounded off as fast as he could, but Wing-go-wing caught hold of Ooroo. Wing-go-wing bit off the bottom of Ooroo’s legs and the end of his tail. Ooroo, though, escaped and bounced into the thick scrub. Wing-go-wing was happy with this little snack and quickly ate what she caught. Ooroo, the now much shorter kangaroo, turned into a pademelon. The pademelon has short legs and a short tail. The pademelon is now always careful of Tasmanian devils and, to this day, wishes it had its longer legs and its longer tail. Wing-go-wing finished her kangaroo nibble but was still hungry. She thought possum would taste nice for dessert. Be-U, the possum, sat in his tree having witnessed what had just happened to Ooroo and he thought he would teach this Tasmanian devil a lesson. Be-U hid behind a stump of an old tree. Wing-go-wing approached, sniffing for possum. Be-U jumped out, holding a sharp stick in one of his paws. He struck Wing-go-wing across the neck and the devil screamed loudly. Be-U, with his other paw, threw white sand at Wing-go-wing and it stuck in the cut. Some of the sand went into Wing-go-wing’s mouth. Be-U scrambled up a tree to see Wing-go-wing below. The devil’s throat was now as white as Mount Wellington snow. From now on other bush animals could see the devil coming before Wing-go-wing could bite them. Wing-go-wing screamed at Be-U. The devil’s voice, though, was now harsh and gravely. The sand had changed the devil’s noise. The other bush animals would hear her coming and know to run away before it was too late. Be-U, hanging by his tail, laughed at Wing-go-wing, and was very happy that he could help his bush friends. But he knew he would always have to be watchful, especially at night, of Tasmanian devils who were hungry . . . and angry . . .1

The Tasmanian devil has the distinction of being the world’s largest living marsupial carnivore, though since an adult male devil seldom weighs more than 12 kilograms the species cannot be compared with dominant placental carnivores in other parts of the world, such as lions, tigers and wolves. Many factors, operating across millions of years, have resulted in the devil occupying this unique position.

These prints on an iced-over creek demonstrate the unusual gait of the devil, which may have descended from an arboreal ancestor that hopped along branches. (Courtesy Nick Mooney)

Australia once formed part of the southern hemisphere super-continent of Gondwana, together with what would become South America, Antarctica, Madagascar, New Zealand, India and Africa. While it is not known precisely how Australia’s marsupials evolved, fragmentary fossil evidence suggests that lineages of protomarsupial stocks originating in South America journeyed across the then-temperate Antarctic landmass. Australia became a continent about 45 million years ago, floating free with a cargo of flora and fauna that would evolve in isolation until the continent collided with the Indonesian archipelago. That isolation enabled marsupials to diversify free of competition, but the ‘floating laboratory’ created competition of another kind, in the form of major climate changes brought about by variation in global weather patterns, Australia’s northward movement towards the equator, and the southern hemisphere ocean, wind and pressure changes created by that movement. Enormous inland seas and tropical forests came and went, periodically giving way to colder, drier conditions.

Although the continent had at times supported big mountain ranges, its general overall flatness provided little protection from the subantarctic winds that scoured away much of its surface. The remaining nutrient-poor soils, increasing surface salinity, decreasing rainfall, and extreme fluctuations between day-time heat and night-time cold, determined the long-term evolution of unique, often sparse, tree, plant and grass forms. Australia’s herbivores developed accordingly. They became either nocturnal or crepuscular (active at dawn and dusk) browsers and grazers. There were none of the vast herds of grazing animals that developed on the lush grasslands of Africa and North America, for example, so there was limited scope for predators.

The devil’s unknown ancestors may well have been tree-dwellers, eating insects, nectar, fruits and young leaves. As those creatures grew larger, their hind legs may have begun to operate in unison to cope with moving along branches, leading eventually to the hopping gait that is characteristic of many marsupials. This may even explain the devil’s unusual gait.

The devil’s specific lineage appears to be a result of dramatic climate change around the middle of the Miocene Epoch (16 million–5 million years ago). Australia had experienced a long period of warm, moist conditions. Inland seas and rivers dominated the continent and supported a great variety of animal, bird and aquatic life. Not surprisingly, many types of predators flourished in that period. But the rapid onset of the first of many ice ages changed that. Colder, drier conditions shrank the forests until, ‘at its peak, far more than half of the continent became technically arid’.2 Major extinctions resulted.

A few carnivores survived. Two were ancestors of the thylacine and the quoll genus, both of them hunters. It may be that specialist scavenging came to be an important niche, with the thylacine in particular ensuring a supply of carrion through its habit of selective feeding. This may be how the devil line arose. The species has no known earlier ancestry, unlike both the thylacine and quoll, which trace back at least 25 million years. The extinct species Glaucodon balabacensis from the Pliocene (around 5 million–2 million years ago) is described as an ‘intermediate form’ between quoll and devil.3 Although this suggests evolutionary experimentation in response to the increasingly dry environment, speculation based on fragmentary fossil evidence must be treated with care.

Australia’s Miocene fossil record was considered poor until, in the early 1980s, the rich Riversleigh fossil deposits in northwestern Queensland were properly surveyed. At some 100 sites, huge numbers of limestone-encased fossils are preserved in ancient cave systems and waterways. ‘Almost half of what we know about the evolution of Australian mammals in the last 30 million years comes from bones found at a single site in the Riversleigh fossil beds. Half of that was unearthed in one hour.’4

Riversleigh was granted World Heritage status, together with the much younger limestone fossil sites at Naracoorte Caves, in southeastern South Australia. There the devil is represented in the extraordinarily rich Fossil Chamber, a huge cave into which animals fell over a period of some 300 000 years, creating a gigantic cone of well-preserved bone deposits. Although Naracoorte and Riversleigh contain a wealth of information yet to be tapped, they have enabled a vivid reconstruction of Australia’s relatively recent but mysterious age of marsupial megafauna.

These giant creatures established themselves as the continent became colder and more arid. They dominated during the most recent Ice Age into the Pleistocene Epoch but were then subject to rapid mass extinction, a process that began about 70 000 years ago and ended when the last of them died away about 20 000 years ago, though these time-spans are as controversial as the reasons put forward to explain the extinctions.

Sarcophilus laniarius is the devil species found in the Naracoorte Fossil Chamber. It was about 15 per cent larger than a modern devil, making its body mass about 50 per cent greater. But caution is necessary. ‘The relationships between the living Tasmanian Devil and the larger Pleistocene form are in doubt . . . The living animal may either be a dwarfed version of S. laniarius or possibly a different species that coexisted with the latter.’5 It was the eminent nineteenth-century palaeontologist Richard Owen (who discovered and classified S. laniarius) who originally proposed the idea of different coexisting sizes, based on fossils discovered in the Wellington caves of New South Wales in 1877.

Giant devil bones have also been found in Queensland, Western Australia, New South Wales and Tasmania. The earliest fossil evidence is from the Fishermans Cliff locality in southwestern New South Wales, where the species is described as S. moornaensis. The first appearances of S. laniarius are in a fossil deposit in the eastern Darling Downs of southeastern Queensland, and in the Victoria Cave deposit in South Australia. Dating these sites is difficult, but the species certainly was present between 70 000 and 50 000 years ago. The Mammoth Cave site in Western Australia, where S. laniarius has also been found, may be as old as 70 000 years. The Devil’s Lair cave deposit in Western Australia is dated at 11 000 to 30 000 years old and shows evidence of both devils and Aboriginal inhabitants. More recent deposits from the Holocene Epoch (the past 10 000– 11 000 years) are found throughout Australia, including on Flinders Island in Bass Strait.

A fragment of a megafaunal devil jaw in the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery in Launceston is about 50 per cent larger than that of the extant species. It would no doubt have been a most efficient carrion eater because, like the present-day devil, it was designed to consume most parts of a carcass including bones.

It is also possible that the giant devil was a hunter as well as a scavenger. Another such hunter was Megalania prisca (ancient giant butcher), an enormous hunting goanna five or more metres long:

The large skull was equipped with numerous recurved, scimitar-like teeth . . . Like its modern counterparts, Megalania probably scavenged from dead animals, but would have also been able to hunt and kill quite large prey . . . It would also have competed for prey with other large carnivores such as the Marsupial Lion, Thylacoleo carnifex.6

There is considerable debate about this latter statement. For a long time it was believed that Megalania prisca, along with the huge terrestrial crocodile Quinkana fortirostrum and the giant snake Wonambi naracoortensis, were the dominant Ice Age land predators—consigning the mammals to a lesser, inferior role. But according to University of Sydney palaeontologist Dr Stephen Wroe, ‘the role of Australia’s fossil reptiles has been exaggerated, while that of our marsupial carnivores has been undersold. The image of an incongruous continent dominated by reptiles in the Age of Mammals has real curiosity value, but it is a castle in the air’7 Wroe’s assessment is based on an exhaustive re-examination of comparative weight and size estimates.

Thylacine evidence reinforces the possibility of different-sized devils coexisting as well as occupying a range of predator–scavenger niches. Seven or so genera of extinct thylacine have been discovered, dating back at least 25 million years, in a range of sizes, from that of a quoll (4 kilograms) up to about 18 kilograms. While the larger species were true hunting carnivores, the smaller species were likely to have foraged for reptiles, small mammals and insects. The relationship between devil and thylacine is close enough to infer similar evolutionary traits in the challenging Australian environment.

The demise of the megafauna was both swift and extensive: virtually everything in excess of about 40 kilograms became extinct. This meant more than 50 species. The carnivore family shrank arithmetically and literally, leaving only the devil, the quolls and a single thylacine species representing medium- to large-sized mammal predators. Indeed, all modern Australian marsupials are true survivors, reflecting ‘the considerable evolutionary fine-tuning that has allowed them to cope with the drastically altered climates and escalating environmental stress of the last five million years’.8 But was there something other than smaller size that spared them from the fate of the megafauna? Climate change, human influence, or a combination of the two, have all been proposed as the agent of the antipodean mass extinction.

Climate proponents argue that at the height of the most recent Ice Age, between 18 000 and 22 000 years ago, the Australian environment had become incapable of sustaining large herbivores. Their world shifted from being cold and dry to warm and dry; the bigger the animal, the less adaptable it was to rapid environmental change. Over a relatively short period of time, Australia’s preponderance of rainforest gave way to open woodland, then to savannah, then to desert. Food and water ran out for all but the smaller, more robust creatures, and for some reason there was a fairly specific cut-off body size.

In the absence of irrefutable evidence, can the climate theory be tested? Modern Australia has long been under the influence of the so-called ENSO effect, being the combined influence of El Niño and the Southern Oscillation, the former disrupting the regular rainfall patterns of the latter through cooling of the upper layer of the southern Pacific Ocean. The result across eastern Australia in particular is drought, sustained over perhaps five years before returning warm sea currents create heavy rains and floods. It’s unpredictable and harsh, and the continent’s arid-adapted wildlife reflects that. But there are a few exceptions. The Daintree tropical rainforest system in far northeast Queensland supports abundant and complex populations of flora and fauna, while Tasmania, a significant area of which is Gondwanan remnant forest, supported the carnivorous devil, thylacine and eastern quoll after their mainland extinctions.

Proponents of the human interference theory believe that migrating waves of people slaughtered the megafauna to such an extent that they became extinct. This would have to have taken place well before the peak in late Ice Age climate aridity (to disprove climate as the culprit), and suggestions are that the megafauna began to be slaughtered about 46 000 years ago. This so-called Blitzkrieg hypothesis infers swift and rampant overkilling, as seemingly happened with the New Zealand moas and North America’s mammoths and mastodons. A less bloodthirsty explanation is that regular slaughter for consumption, together with the introduction of fire management, which significantly altered grazing and browsing habitats, induced the same extinction result but over a far longer period. In this context, Stephen Wroe contends that a significant mid-Holocene increase in human land usage could have been a primary cause.9

Did the devil survive because of its comparatively small size and ability to become even smaller (dwarfism)? Or was its place in the ecosystem assured because it was capable of both hunting and scavenging? Even in the absence of easy-to-catch megafauna, did people not hunt it? Why did the thylacine survive but not the larger marsupial lion?

The subsequent extinction of the devil across mainland Australia is also hard to explain. It appears the animal survived there until as recently as 500 years ago, although the introduction of dingoes some 6000 years ago is generally considered to have marked the beginning of their end. Their predator– scavenger niches overlap; dingoes will forage for young devils; and there have never been dingoes in Tasmania.

There may in addition have been a climatic factor. Devils thrive in temperate, well-covered Tasmania with its abundance of prey in a relatively compact area. Much of mainland Australia, on the other hand, has become an ever more arid and inhospitable environment since the devil survived the megafaunal extinction. Perhaps those conditions affected the mainland species over thousands of years until it was reduced to remnant populations in the east and southeast. Then, and only then, might the devil have succumbed to the dingo.

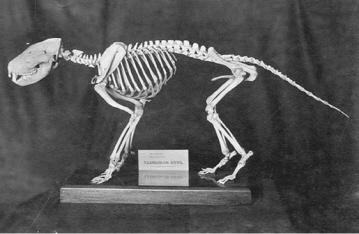

Skeleton of Sarcophilus harrisii, the Tasmanian devil. (Courtesy Collection Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery)

Megafauna-era butchering tools include scrapers of all kinds as well as axes, but it was not until some 10 000 years ago that the Aboriginal people became true hunters, with the invention of the boomerang and spear. It is suggested that prior to those technological advances, animal-taking must have been somewhat opportunistic. The famous Devil’s Lair cave in south-west Western Australia, named for the extinct Tasmanian devil bones found in it, provides a clue.

Devil’s Lair cave is one of the most important in Australian archaeology. By dating human occupation back some 45 000 years,10 it confirms a much earlier human presence in the arid centre. Human markings on the walls may be the oldest on the continent. Cultural artefacts of bone and marl are also among the oldest known. Many extinct species are represented, but it appears that giant kangaroos were the primary food item, followed by wallabies and possums. If the devil was a food source, the scarcity of devil bones in the cave indicate either its rarity or a disinclination to catch and eat it. Of course, devils also live in caves.

There is, however, more recent evidence of the devil as a food source. Archaeological work at Victoria’s Tower Hill Beach kitchen middens records 5000-year-old devil bones. Very few middens with devil bones have been found, but this did not stop one authority from declaring, ‘the Aborigines knew how to hunt it, and they used it for food’.11

Writing in 1910 Fritz Noetling, Secretary of the Royal Society of Tasmania, cited a complete lack of evidence that Tasmanian Aborigines consumed any of the marsupial predators or monotremes. ‘It is undoubtedly very remarkable that even at the low state of civilisation represented by the Aborigines, human beings preferred the flesh of the herbivorous animals, and declined to eat that of the carnivorous.’12 If this is true it may partly explain why in Tasmania devils and humans coexisted for tens of thousands of years prior to European settlement.

One of the greatest finds in Australian cultural history was made at Lake Nitchie, north of Wentworth on the Victoria–New South Wales border, in 1970. A male human skeleton, possibly 7000 years old, lay in a shallow grave. Unusually tall, he was wearing a necklace of 178 pierced Tasmanian devil teeth, collected from at least 47 animals. It has been speculated that the necklace indicates a dwindling population of Sarcophilus, and that it was considerably older than the skeleton. Archaeologist Josephine Flood went further: ‘Indeed, if such necklaces were common, it is not surprising that Tasmanian devils became extinct’.13 It is a startling suggestion, that the animal may have been hunted to extinction for its teeth.

On the other hand, the necklace is one of very few known to exist and required great labour to produce; this suggests it may have been of major significance. It is tantalising to speculate that the devil may therefore have held a special place in at least some societies of the distant past.