Arnold Schoenberg and Wassily Kandinsky were authentic politicians of the spirit who changed the most elemental assumptions of their respective cultural domains. Each chose to imagine the possible rather than simply assume it. Each illuminated the realm of experience in his own way and, in the process, contributed to an education of the senses. Their intense, if brief, correspondence is consequently of aesthetic and historical importance. It clarifies not only the remarkable interplay between music and painting in their art but also the attempt of the cultural vanguard to break down the barriers between them. Schoenberg and Kandinsky had their differences. But they were ultimately opposing expressions of a single spirit. Their correspondence illuminates the radical vision of modernism—and that of the age as well.1

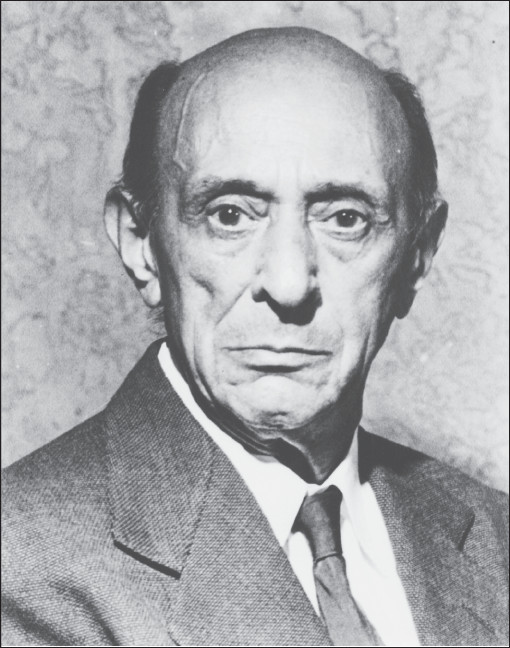

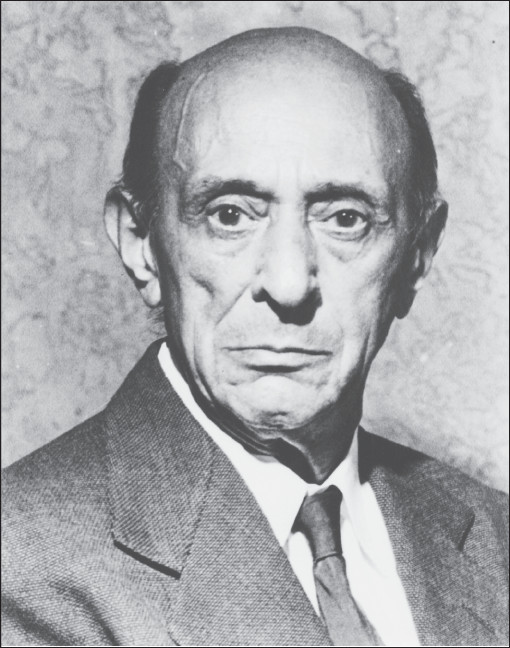

Arnold Schoenberg was eight years younger than Wassily Kandinsky. The father of the composer had died early in life, and the son learned banking before turning to music as a profession and entering the world of Viennese bohemia. Schoenberg was ambitious; believing it would help his career, he converted from Judaism to Protestantism in 1898, only to convert back during the 1930s as a form of political protest. This may explain his unprovoked outburst against the supposed anti-Semitism of Kandinsky, about which he had been informed by Alma Mahler-Werfel,2 and which essentially brought the correspondence between the two artists to an end in 1923.3 In any event, from the beginning Schoenberg participated in the bohemian subculture of Viennese modernism. It was in the famous Café Griensteidl that he encountered Alexander Zemlinsky, the mentor of Gustav Mahler, who became his first teacher in composition and whose sister he married in 1901. His new wife, for her part, soon enough had a tumultuous affair with the young expressionist painter Richard Gerstl, who committed suicide when she broke it off. This was when Schoenberg began painting, and the scandalous context helps explain the obvious erotic frustration, the anxiety-ridden character, and the romantic impulse of his art during this period. Notoriety accompanied him from the start—along with a lack of money. Gustav Mahler became his friend, taught him that music must express the authentic personality of its creator rather a general understanding of the “beautiful,” and tried to help financially by anonymously buying some of Schoenberg’s paintings in 1910. A few years later the young composer swallowed his pride and accepted a grant from the city of Vienna, firmly ruled at the time by its anti-Semitic mayor, Karl Lueger. Yet Schoenberg rejected a professorial position at the University of Vienna in 1912. He stated, in good bohemian fashion, that he did not wish to be tied down. Nevertheless, something else influenced his decision.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Music Division, LC- USZ62–52575

Vienna was known both for its classical past and for the assault on it. The city boasted composers like Mahler and those of Schoenberg’s musical inner circle, including Alban Berg and Anton von Weber.4 But it was also the city in which Hugo Wolf, whose highly sentimental works so enchanted Rosa Luxemburg, had just died. It was the city in which The Blue Danube (1866) still ruled supreme, and in which archreactionary critics like Hans Pfitzner could decry Schoenberg’s “atonal chaos” and later liken his works to cultural bolshevism.5 Vienna mixed grand historical tradition with the experimentalism of the modernists and the provincialism of the narrow-minded petty bourgeois—as becomes so clear in the wonderful novella by Ödön von Horváth, Der ewige Spiesser (1930). Schoenberg’s attitude toward the city of his birth was thus ambivalent. It would always remain, for him, “our beloved and hated Vienna.”6 His music reflected the city’s cultural complexity and was rooted in the legacies of Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, and Mahler. Indeed, beginning with Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht of 1899, in which he first moved away from the major-minor key system, his music involved a constant interchange with these predecessors.

The situation was different with Kandinsky. He had emigrated from Russia to Munich, often called the sister city of Vienna, known for its easy-going style, its liberalism, and its bohemian subculture prior to World War I. But there were no comparable giants of painting in its history. Kandinsky thus viewed his art as a rupture with the canon. It was also only natural that he should have understood Schoenberg’s project in the same terms when he first heard the radically innovative Second String Quartet, op. 10, and the Three Piano Pieces, op. 11, written between 1907 and 1909—works that would prove so important for the composer’s later serial compositions. Alexei von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin, and Gabriele Münter attended the same concert as Kandinsky. They were prominent members of the Neue Künstler Vereinigung of Munich, whose three exhibitions of 1909–11 had introduced the German public to Picasso, Braque, and Derain.7 The association, however, was dominated by a host of mediocre painters employing impressionist techniques, and at the time, under the influence of Franz Marc, Kandinsky had decided to break with it in order to pursue a more antirepresentational path. No wonder then that these major painters should all have been drawn to the Viennese maestro already engaged in an attempt to “emancipate dissonance” through atonality.

Wassily Kandinsky only began painting at the age of thirty. The son of a privileged family, he had decided on an artistic career when he gave up his law practice and the opportunity for a professorial position at the University of Dorpat. The years prior to his encounter with Schoenberg were marked by the production of work in any number of styles.8 Most striking perhaps are the paintings influenced by the poetic quality of Jugendstil, the German version of art nouveau, during its most radical period, as well as the color experiments of the Fauves. The bright and lively works of these early years were often marked by a symbolism derived from exotic visions, fairy tales, and Russian legends. Paintings like Das bunte Leben (1907), which anticipated Kandinsky’s later nonobjective experiments, are indicative. There, on a black background, are images of knights riding through an indeterminate landscape populated by lovers, in which a festival of an indeterminate Volk is taking place. Pastels identify what remain of the natural objects, while their interiority emanates a brightness enhanced by the clash of primary colors. It is legitimate to compare Kandinsky’s canvases of this time to Schoenberg’s most important expressionist works, including Pelleás und Mélisande (1903), as well as to compositions like Gurrelieder (1900) and the song cycle built on Stefan George’s The Book of the Hanging Gardens (1910), which Schoenberg only completed in 1911 and which introduced the atonal style and the emancipation of dissonance.

In the same way that three-point perspective served as the foundation for traditional painting, what is generally known as classical music rested on the diatonic scale and the tonic triad, or the defined key. Wagner, Johannes Brahms, and Mahler had all contributed to freeing dissonance, or movement, from this defining structure, just as stylistic revolutionaries like Manet and his impressionist followers, including Monet (especially in his haystack series), sought to free aesthetic experience from reliance on the representational object and three-point perspective. James Joyce, Marcel Proust, Robert Musil, and Virginia Woolf transformed narrative; they structured plot around the diverse associations of inner life, and transvalued the literary canon in accordance with the logic of their expositions. Verhaeren and others were, in a similar vein, exploding linguistic constraints in the name of free verse while Alfred Jarry, Frank Wedekind, Ibsen, Strindberg, and (later) Brecht were—each after his fashion—engaged in challenging classical theater’s Aristotelian presuppositions. Thus Schoenberg’s and Kandinsky’s works appeared in tandem in an international context rife with modernist assumptions.

Each had heard of the other. But Schoenberg had already produced his first “free atonal” compositions before he ever met Kandinsky, who had also begun experimenting with nonrepresentational modes of painting before their encounter in 1911. The wonderful painting In an Oriental Vein by Kandisky appeared in that same year. 1911 also marked the publication of both Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art and the writing of Schoenberg’s Theory of Harmony (1922), which he dedicated to Mahler. It was also the year that Kandinsky began planning the justly famous Blaue Reiter exhibition, to whose almanac Schoenberg would contribute two drawings and an essay entitled “On the Relation to the Text” (1912). Schoenberg and Kandinsky were many-sided in their aesthetic interests. Both sought to overcome what they considered the “artificial” divisions between different forms of artistic expression. Both also shared a belief in what the painter termed the “inner necessity” and the composer the “inner compulsion” underlying all artistic activity. This impulse generated by the all-embracing “spirit” of art was what Kandinsky used to justify his insistence on the connection between music and painting. He liked to play the cello, and the titles of many works such as Great Fugue (1896), Scherzo (1897), and Composition IV (1908) refer to his belief in the translatability of the genres. Nor was the boundary between music and painting any more fixed for Schoenberg. He had already begun to paint when they met, and in 1916 he entitled one of his Five Pieces for Orchestra, op. 16, “Colors” (Farben). Indeed, this work can be seen as a forerunner of the “sound-color” (Klangfarben) compositions that have become common for contemporary postserial music.9

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC- USZ62–72260

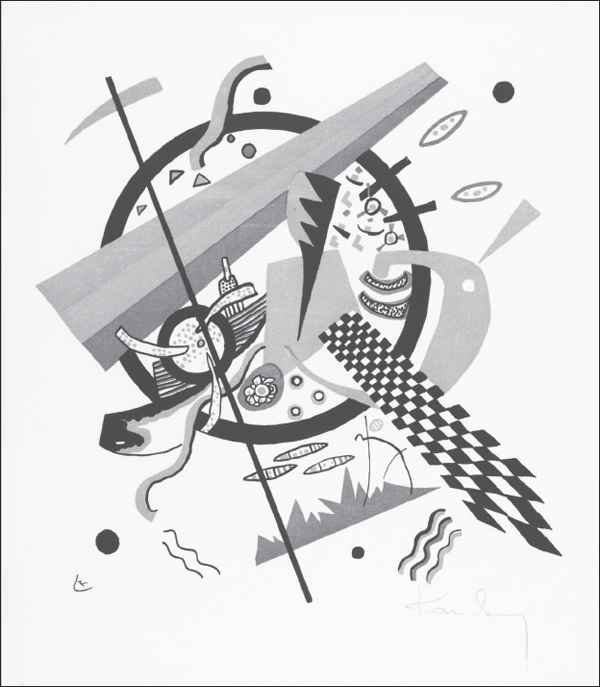

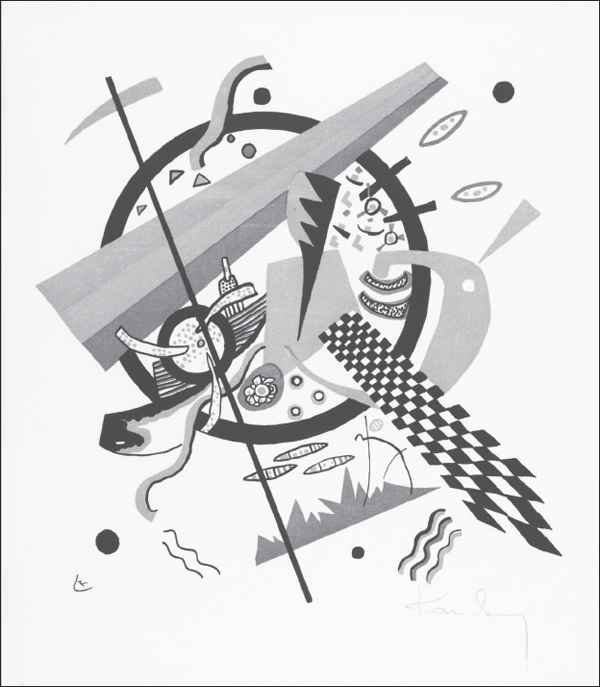

Belief in the translatability of artistic genres led to a concern with their unification. Kandinsky and Schoenberg, like many other modernists, thought that the spirit of art inherently contested the division of labor. Wagner’s ideal of the total work of art became an ideal for Schoenberg in The Lucky Hand (1910) and Kandinsky in The Yellow Sound (1912). These works have rarely been performed and actually evidence far more hyper-romantic, indulgent, and pretentious qualities than many might care to admit. Each, however, turns the component elements of an opera against one another in order to increase the sense of estrangement as well as the active participation of the audience. Their lack of theme, narrative, and plot also constitute an assault on the fixed and finished product of the creative impulse. Illuminating this nonrepresentational spirit by eliminating all external trappings is a technique common to both Kandinsky and Schoenberg. The painter, for example, reduced the work of art first to color and then, following his association with the Bauhaus in 1922, to a preoccupation with geometric forms that defined colored shapes on glowing planes. Small Worlds IV (1922) can be seen as an important transitional work that would ultimately lead Kandinsky to new inventions, like his magnificent late work Around the Circle (1940). This shift is reflected in Kandinsky’s aesthetic theory, as Concerning the Spiritual in Art makes way for From Point and Line to Plane, published in 1926. A parallel development took place when Schoenberg moved from his initial experiments in free atonality to the famous twelve-tone technique, where each tone is dependent on the other, in his Suite for Piano, op. 25 (1921). Indeed, for both artists the aim remained the same: to convey the unique sensation.

The “inner voice” alone should speak. It is what gives meaning to the work’s character and quality. But this voice cannot be grasped by just anyone. Schoenberg thus wrote to Kandinsky on January 24, 1911: “There is no question of my works winning over the masses. All the more surely do they win the hearts of individuals—those really worthwhile individuals who alone matter to me.… One must express oneself! Express oneself directly! Not one’s taste, or one’s upbringing, or one’s intelligence, knowledge or skill. Not all these acquired characteristics, but that which is inborn, instinctive.”10 Both Schoenberg and Kandinsky were preoccupied with the inner life, the expression of unconstrained singularity. Neither was concerned with developing a fixed and finished system. Both, in fact, refused to prize any particular style for its own sake. And this made it possible for them to keep their radicalism intact beyond the changes their styles underwent. Each believed that the inner necessity motivating him would change as the world changed. Each was unafraid to adapt as different forms of modernism became integrated into the cultural framework of modernity. Economizing or suspending artistic effects like melody, which supposedly obscured the “subcutaneous,” or the spirit, was Schoenberg’s aim from the very first. Giving every tone its uniqueness, and only later making each structurally dependent on the others in a given row is an expression of this impulse. The twelve-tone technique, in this vein, has its roots in the early work, and what Schoenberg wrote to Kandinsky on September 28, 1913, had a certain general significance: “I certainly do not look down upon [the

Gurre-lieder] as the journalists always suppose. I have not improved, but my style has simply got better so that I can penetrate more profoundly into what I had already had to say earlier and am nevertheless capable of saying it more concisely and fully.”

11

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Free atonality had initially rendered the distinction between dissonance and consonance, harmony and chaos, meaningless. If not in practice then in theory (which is telling), these terms lost their antinomial character and assumed a dynamic relation to one another. Schoenberg would have agreed with Kandinsky’s statement that “today’s dissonance in painting and music is merely the consonance of tomorrow.” Their art evidenced an “anticipatory consciousness” even as it illuminated, using another term from Ernst Bloch, “the hollow space” of the age. An “atmosphere,” a spirit of expectation, emerges from the emptiness that is reflected in the music of Schoenberg with its “noiseless dynamite, long anticipations, suspended arrival.”12 This interpretation also applies to Kandinsky, who saw colors as metaphorical equivalents of mood states by which the inner reality of the artist might be experienced by an engaged audience. Breaking art off from the world of appearances frees the spirit and thereby makes the inner experience of life the central object of aesthetic concern. The immediacy of experience brings with it an anticipation of what can be. Thus Kandinsky could say in his letter of November 16, 1911, that “I feel more and more strongly in every work an empty space must remain, that is, not bind! Perhaps this is not an ‘eternal’ law, but a law of ‘tomorrow.’”13

The Spirit in Action

Just as Kandinsky’s paintings demand of a viewer the willingness to experience a given mood, Schoenberg’s music “asks of the listener that he or she spontaneously co-compose its inner movement and, instead of contemplation, challenges him or her to engage simultaneously in praxis.”14 Precisely insofar as these artists aimed at eliminating the unifying point of reference, in terms of the musical triad by the one and the consensual object by the other, their works sought to elicit a new connection between the artist and the audience. The meaning of the work ever more surely rested on the sense of subjectivity it generated. “Self-perception” was, as Kandinsky expressed it in his letter of January 26, 1911, “the root of the ‘new art’, or art in general, which is never new, but which must only enter into a new phase—Today!” The music of Schoenberg, no less than the painting of Kandinsky, dared the audience to find out whether unique forms of experience were still possible in the standardized world of modernity, whose nascent culture industry was already seeking the lowest common denominator in order to maximize profits.

Other artists and cultural producers immediately grasped the innovative techniques introduced by Kandinsky and Schoenberg. An unattributed editorial for the journal of the Viennese Secession, Vers Sacrum, in fact noted: “It is jokingly asked today whether artists only work for artists. We answer, quietly, yes! But with the noble title of artists we name not only the people [who] carry around palettes, brushes, but rather those who try to also emapthize anew [nachempfinden] or also recreate [nachzuschaffen] art. We live from the belief that their number is growing.”15 Yet Kandinsky and Schoenberg would surely have been amazed at the millions who now enjoy their art. They were, after all, part of a self-selected avant-garde that was becoming seemingly more radical from day to day. Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, and the artists of the Viennese Secession of 1897 may have exerted a certain influence on the new visionaries. Their use of line led directly to cubism, while their etherealizing of the represented object served as a source for expressionism. By 1911, however, their deep psychological preoccupation with sexuality and the decorative quality in so much of art nouveau had seemingly become domesticated.16 New heroes were already entering the scene: Marinetti, Kokoschka, and a host of others. The Viennese version of art nouveau, popularly known as Secessionstil, could still shock the good bourgeois. Nevertheless, it had already grown too stale for the tastes of revolutionaries like Kandinsky and Schoenberg.

Their experiments stood apart from the conflict raging between those artists concerned with the “functional” and others with the “ornamental” that had so dominated the aesthetic discussions in Vienna as the century drew to a close. Representatives of both tendencies already had been integrated into the status quo. Schoenberg and Kandinsky moved forward by looking back to the nineteenth-century romantics who claimed that the aim of art was less the depiction of some narrative or the imitation of nature than the expression of certain feelings or fantasies. The inner image remained for them the foundation of painting. On April 9, 1911, Kandinsky complained in a letter to Schoenberg: “How immensely fortunate (though only relatively!) musicians are [to be engaged] in their highly advanced art, truly an art which has already had the good fortune to forgo completely all purely practical aims. How long will painting have to wait for this? And painting also has the right (= duty) to it: color and line for their own sake—what infinite beauty and power these artistic means possess!”17

In contrast to painting, however, music had never been forced to define itself in relation to an objective referent. But that did not make its internal rules of construction any less strict. Quite the contrary: historically produced conventions hardened in music perhaps more drastically than in any of the other arts. Embarking on a new artistic direction was no easier for Schoenberg than for Kandinsky. The latter explained his motivation nicely in a letter to his friend on February 6, 1911, by noting that “the human tendency toward the fossilizing of form is shocking, even tragic.” On August 19, 1912, Schoenberg responded:

Progress now becomes identified less with some teleological unfolding of history or linear development of science than with a growing inner awareness of existential questions concerning life’s meaning. Artworks can never fully articulate it. At best they can only offer intimations, or what Karl Jaspers termed “traces” of the “all-encompassing,” “the essence of essences,” or “the god-head.” The ungraspable constantly eludes what the inner compulsion calls on the artist to grasp. There is only the growing knowledge of an unending quest for self-expression and self-perception, evidenced through the invention of ever more complicated techniques. Thus Kandinsky stated in a letter of August 22, 1912, that “‘inner necessity’ is just a thermometer (or yardstick), but one which leads to the greatest freedom and at the same time sets up the inner capacity to comprehend as the only limitation on this freedom.”19

External time devolves into le durée of Henri Bergson, what Edmund Husserl defined in 1905 as the internal consciousness of time, or what Heidegger later called “temporality.” Inner time is divorced from clock time, and the “hollow space” of subjectivity denies any spatial constriction. Mediation between the inner and outer worlds is no longer possible. Experience of the sublime escapes definition by any category or concept. That is the sense in which modernist art becomes autonomous. No longer is there an objective or representational referent for understanding the work. Where Kandinsky’s explosion of the object produced a burst of colors that evoked a cacophony of emotions, Schoenberg sought to subject traditional music to a rigorous and rational critique. But he was no less revolutionary than his friend. Thomas Mann correctly noted that with Schoenberg the “effect is just the converse of rationality. Over the head of the artist, as it were, the art is cast back into a dark mythological realm.”20

Both Schoenberg and Kandinsky resisted the looming triumph of instrumental rationality. They had only contempt for a disenchanted world, and attempted to reenchant it. The ambition to do so is exhibited by Schoenberg’s great opera Moses and Aaron (1928) and his oratorio Jacob’s Ladder, which he composed in 1906, as it is by the nonobjective compositions of Kandinsky.21 Religious preoccupations stayed with Schoenberg throughout his life. Meanwhile, Kandinsky embraced the theosophy of Madame Blavatsky, whose iconography and mysticism helped him find his nonobjective avenues to the absolute, or spirit.22

Kandinsky and Schoenberg wished to retrieve a forgotten past. The contributions of non-western societies informed their work. To be sure, colonial peoples were, following Schiller, identified with the childhood of civilization and a golden age. Like children, the insane, and animals, they were embraced for their supposed innocence and seen as uncontaminated by the worst elements of modernity. In spite of this ethnocentrism, however, the products of nonwestern and premodern art were taken seriously. Early Russian iconography influenced Matisse, Japan touched Van Gogh, and Tahiti inspired Gauguin. Medieval sculptures had a profound aesthetic impact on Ernst Barlach, and the Byzantine mosaics at Ravenna contributed much to The Kiss (1908) and other works of Gustav Klimt’s “golden period.” The interest of modernists in the instinctive, primordial, and mystical gave an international stamp to their project. Their combination of cosmopolitanism and nonconformism led them to challenge European standards for evaluating art to the point where “the arts of subjugated backward peoples, discovered by Europeans in conquering the world, became aesthetic norms to those who renounced it. Imperialist expansion was accompanied at home by a profound cultural pessimism in which the arts of the savage victims were elevated above the traditions of Europe.”23

Modernism treated western conventions as little more than constraints. Kandinsky and Schoenberg invented their own traditions. They joined the other great artists of this cultural vanguard in innovatively employing the contributions of manifold figures and cultures often lost within what had become rigidified and Eurocentric notions of art history. Their views of Africa, Asia, and Latin America were often naive, ill-informed, and sometimes even self-serving and exploitative. Nevertheless, modernism looked beyond Europe for inspiration and—perhaps for the first time—gave art a global imprint.

Antinomies of the Spirit

The world of modernism was still young when Schoenberg was starting to compose and Kandinsky was beginning to paint. They shared certain presuppositions concerning the “inner” genesis of art, its experimental confrontation with convention, and its explosion of a consensual point of reference for the work. Schoenberg undoubtedly agreed with a letter from Kandinsky of February 6, 1911, that stated: “This human tendency toward the fossilizing of form is shocking, even tragic.” Both believed that art was grounded in life. Both sought to break down rigid oppositions between the abstract and the concrete, matter and spirit, and to deny any fixed characteristics of sensory experiences like hearing or seeing. Both viewed the spirit as translatable from one medium into another, and Kandinsky, in particular, considered it possible to hear colors and see music. In all these ways it is legitimate to ask: “Does not the dissolution of the portrayed object correspond to the dissolution of traditional tonality in music? Does not the emancipation of colors and forms (their collisions and disproportions) correspond to the emancipation of dissonance? And do not both correspond to the dissolution of grammar and syntax, which began about the same time.”24

Both Kandinsky and Schoenberg were radicals, and they knew what they wished to transform. They confronted their respective genres with an eye toward a permanent revolution of creativity wherein the subjectivity of the viewer or listener would be constantly pitted against the world of artistic conformity. But they did so with different means and for different ends. Kandinsky may have spoken respectfully about Schoenberg’s often dreamlike portraits and landscapes, so reminiscent of Edvard Munch, but he was suspicious of the extent to which they retained a representational or organizational frame of reference. The assumptions they held in common, furthermore, often meant something different to each of them. Kandinsky wrote Schoenberg on January 18, 1911, for example, that “the independent life of the individual voices in your compositions is exactly what I am trying to find in my paintings.… Construction is what has been so woefully lacking in the painting of recent times, and it is good that it is now being sought.… I am certain that our own modern harmony is not to be found in the ‘geometric’ way, but rather in the anti-geometric, anti-logical way.”25 In his letter of August 19, 1912, however, Schoenberg stated that The Yellow Sound, which apparently shared so much with his own Lucky Hand, was actually “the opposite of construction. It seems that he who constructs must weigh and test. Calculate the load capacity, the relationships, etc.” The composer saw the work of his friend less as a product of construction than a “renunciation of conscious thought” and the expression of an “inner vision.”26

Kandinsky and Schoenberg were antinomial expressions of modernism in its golden age. Kandinsky sought only an empathetic feeling of immediacy on the part of the onlooker. Like others who had come from the Viennese Secession,27 he would have been thrilled to receive appreciation from a child. Especially in his early work, it was the immediacy of experience that he sought to convey. With Schoenberg it was different; he conceded nothing to immediacy and made every possible demand on the intellectual faculties of the listener. Schoenberg noted in his letter of January 24, 1911: “I believe that it will eventually be possible to recognize the same laws in the harmony of those of us who are the most modern as in the harmony of the classics; but suitably expanded, more generally understood.” Kandinsky had a different take on the matter. He understood color as reflecting a particular mood, which an artist simultaneously seeks to express and elicit, and for which any limiting line serves as a constraint. The situation is different for music. The twelve-tone scale constitutes a stringent compositional form capable of giving each tone its singularity by reorganizing musical expression. This was precisely what Thomas Mann understood as the subversive preoccupation with organization on the part of Adrien Leverkuhn, a blending of Nietzsche and Schoenberg, who served as the main character in Dr. Faustus. In contrast, even Kandinksy’s later geometric paintings were never “organized” in the sense that “the musical phenomenon reduces itself to the elements of its structural interconnections.”28

Both may have concerned themselves with the “unlogical,” or what Schoenberg termed the “elimination of the conscious will in art.” But for Schoenberg, this elimination required the logic of composition that he formulated in The Musical Idea and the Logic, Technique, and Art of Its Presentation (1910). The “emancipation of dissonance” necessarily presupposes the harmony it denies. Even with regard to the early atonal work, in this vein, Schoenberg’s music is arguably more analogous to the cubist paintings of Picasso or Braque than to those of Kandinsky. These cubists, in creating the illusion of reducing three dimensions to two, clarified the assumptions behind not just deconstructing the object but reconstructing it as well. Surface and depth blended together and the canvas became a set of transparent fragments. But the object never entirely disappeared; it was merely transfigured. The same holds for the new music. The emancipation of dissonance only makes sense with reference to a preexisting notion of harmony, even if its value has been undercut and its function transformed. Thus, perhaps in spite of Schoenberg’s own wishes, his work retains a positive and objective point of reference.29 Kandinsky’s paintings lack any such referent or moment of positivity. That is also the case for much of the later work in which he rejects the broad expressionist brushstroke, the dramatic black line, the dabs of paint, and the shaded colorings of the abyss in its manifold dimensions. Kandinsky may have moved from color to line. But the step was not as great as it initially appears.30 Geometry merely provides the autonomous laws and axioms within which color gains its effect and the imagination can play. The materials renounced are still never explicitly defined, and his interest in form remains of the immaterial sort originally represented in the early works like Little Pleasures (1909) and Black Lines (1913).

Kandinsky was never concerned with multiplying the representational possibilities of the object in the manner of Schoenberg, whose assault on the triad in the name of a “free atonality” expanded the tonal combinations employed in prior forms of music. Kandinsky was far less preoccupied with the logic of composition than Schoenberg, who has often been called a “conservative revolutionary” (without any political connotations). Tradition played a stronger functional role for Schoenberg, who sought to “break through the limits of a bygone aesthetic,” than for Kandinsky, who believed that the act of aesthetic production, the sense of inner necessity, would reveal what was salient from the past. Kandinsky rejected all “coloristic balancing acts,” traditional techniques, or immanent attempts to transform the visual inheritance of the past. He was intent on making an absolute break, whereas Schoenberg, by way of contrast, considered his twelve-tone system to be the “legitimate heir” to the classical seven-tone system.31 The composer was not, of course, some tradition-bound reactionary. He surely would have agreed with Kandinsky that it is “wrong for the teacher to instruct the pupil in art in the same way a sergeant-major instructs a soldier in the use of firearms.… Rather his task is to open before his students’ eyes the doors of the great arsenal of resources, ie. means of expression in art, and to say: Look!”32

However, for Schoenberg, it was also a matter of teaching students “to express themselves.”33 Knowledge of harmony and counterpoint were necessary for him in a way that the knowledge of classical anatomy was not for the painter preparing an assault on representation. Schoenberg’s work was built on the edifice erected by Brahms. He insisted that, before learning “the new music,” his students should learn the old. Schoenberg would never have accepted Kandinsky’s claim that “once painting no longer recognizes organic-anatomical construction, ie. consistently rejects it in favor of linear-painterly construction, does it not follow that one should exclude from one’s instruction all the preliminary exercises practiced by earlier schools, in particular the mastery of organic-anatomical construction?”34 The precise use of compositional rules was essential for Schoenberg, while for Kandinsky, artistic creation was inherently intent on shattering anything capable of constraining its spirit. The composer employed an unyielding logic, and he considered beauty a mere by-product of the truth generated by art. It was different with his friend. The beautiful was both the means and the end of the work, and for this reason, it could only exist as a fleeting illusion and momentary experience that was still more real than reality itself.

The loneliness, repressed eroticism, and anxiety evident in so many of Schoenberg’s self-portraits, with their use of flat surfaces, direct expression, and bare landscapes have little in common with the brightness and joyful expression of colors in the work of Kandinsky. The playfulness and utopian wonder of the liberated imagination in Kandinsky’s paintings find no parallel either in the music of the maestro or Schoenberg’s still-representational paintings like The Red Gaze (1910). Kandinsky always understood that his art was building an experiential bridge with the viewer; Schoenberg understood his music as a “cry for help.” The inability to grasp the sublime only heightens the momentary intimations of its existence. Just as Schoenberg’s work evidenced an irratio of the ratio, Kandinsky’s forwarded the ratio of the irratio. The concern with freedom demands the preservation of form, just as the preoccupation with a lived fantasy seeks form’s end. The works of Schoenberg and Kandinsky, in this sense, oppose one another within a unifying frame of reference. They complement as well as reflect one another. They are not the same. And that is as it should be: genius is always unique.