Fig. 2. Crayon portrait (1854) by Samuel Worcester Rowse. Reproduced from The Writings of Henry D. Thoreau. The Walden Woods Project Collection at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods. Courtesy of the Walden Woods Project.

You cannot perceive beauty but with a serene mind.

Written November 18, 1857, in his Journal, vol. X, p. 188

There is just as much beauty visible to us in the landscape as we are prepared to appreciate,—not a grain more. The actual objects which one man will see from a particular hill-top are just as different from those which another will see as the beholders are different.

“Autumnal Tints” in Excursions, p. 256

The cart before the horse is neither beautiful nor useful. Before we can adorn our houses with beautiful objects the walls must be stripped, and our lives must be stripped, and beautiful housekeeping and beautiful living be laid for a foundation: now, a taste for the beautiful is most cultivated out of doors, where there is no house and no housekeeper.

Walden, p. 38

How much of beauty—of color, as well as form—on which our eyes daily rest goes unperceived by us!

Written August 1, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIV, p. 3

There are meteorologists—but who keeps a record of the fairer sunsets? While men are recording the direction of the wind they neglect to record the beauty of the sunset or the rain bow.

Written June 28, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 161

Some love beauty, and some love rum.

Written January 22, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 423

Enough for the season is the beauty thereof. Spring has a beauty of its own which we would not exchange for that of summer.

Written March 23, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 76

In what book is this world and its beauty described? Who has plotted the steps toward the discovery of beauty?

Written October 4, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 371

The ears were made, not for such trivial uses as men are wont to suppose, but to hear celestial sounds. The eyes were not made for such grovelling uses as they are now put to and worn out by, but to behold beauty now invisible. May we not see God?

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 382

All the world reposes in beauty to him who preserves equipoise in his life, and moves serenely on his path without secret violence; as he who sails down a stream, he has only to steer, keeping his bark in the middle, and carry it round the falls.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 317

The forms of beauty fall naturally around the path of him who is in the performance of his proper work; as the curled shavings drop from the plane, and borings cluster round the auger.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 318

I was inclined to think that the truest beauty was that which surrounded us but which we failed to discern, that the forms and colors which adorn our daily life, not seen afar in the horizon, are our fairest jewelry.

Written September 18, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 166

Always the line of beauty is a curve.

“The Service” in Reform Papers, p. 6

Every landscape which is dreary enough has a certain beauty to my eyes.

Cape Cod, p. 25

Why not take more elevated and broader views, walk in the great garden, not skulk in a little “debauched” nook of it? consider the beauty of the forest, and not merely of a few impounded herbs?

“Autumnal Tints” in Excursions, p. 256

The beauty of the earth answers exactly to your demand and appreciation.

Written November 2, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 278

Beauty is where it is perceived.

Written December 16, 1840, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 205

To him who contemplates a trait of natural beauty no harm nor disappointment can come.

“Natural History of Massachusetts” in Excursions, p. 5

I spend a considerable portion of my time observing the habits of the wild animals, my brute neighbors. By their various movements and migrations they fetch the year about to me. Very significant are the flight of geese and the migration of suckers, etc., etc. But when I consider that the nobler animals have been exterminated here,—the cougar, panther, lynx, wolverine, wolf, bear, moose, deer, the beaver, the turkey, etc., etc.,—I cannot but feel as if I lived in a tamed, and, as it were, emasculated country. Would not the motions of those larger and wilder animals have been more significant still? Is it not a maimed and imperfect nature that I am conversant with?

Written March 23, 1856, in his Journal, vol. VIII, pp. 220–221

The very dogs & cats incline to affection in their relation to man. It oft en happens that a man is more humanely related to a cat or dog than to any human being. What bond is it relates us to any animal we keep in the house but the bond of affection? In a degree we grow to love one another.

Written April 29, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 210

I see a fox run across the road in the twilight.… I feel a certain respect for him, because, though so large, he still maintains himself free and wild in our midst, and is so original so far as any resemblance to our race is concerned. Perhaps I like him better than his tame cousin the dog for it.

Written November 25, 1857, in his Journal, vol. X, p. 206

The fox seems to get his living by industry and perseverance.

Written February 2, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIII, p. 124

The musk-rat is the beaver of the settled States.

“Natural History of Massachusetts” in Excursions, p. 13

The moose is singularly grotesque and awkward to look at. Why should it stand so high at the shoulders? Why have so long a head? Why have no tail to speak of?

The Maine Woods, p. 115

The bees are on the pistillate flowers of the early willows,—the honey-bee, a smaller fly-like bee with very transparent wings & bright yellow marks on the abdomen, and also a still smaller bee more like the honey bee. They all hum like summer.

Written April 25, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 491

Yet what is the character of our gratitude to these squirrels, these planters of forests? We regard them as vermin, and annually shoot and destroy them in great numbers, because—if we have any excuse—they sometimes devour a little of our Indian corn.… Would it [not] be far more civilized and humane, not to say godlike, to recognize once in the year by some significant symbolical ceremony the part which the squirrel plays, the great service it performs, in the economy of the universe?

Written October 22, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIV, p. 166

Every man says his dog will not touch you. Look out nevertheless.

Written July 23, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 241

The mice which haunted my house were not the common ones.… When I was building, one of these had its nest underneath the house, and before I had laid the second floor, and swept out the shavings, would come out regularly at lunch time and pick up the crumbs at my feet. It probably had never seen a man before; and it soon became quite familiar, and would run over my shoes and up my clothes. It could readily ascend the sides of the room by short impulses, like a squirrel, which it resembled in its motions. At length, as I leaned with my elbow on the bench one day, it ran up my clothes, and along my sleeve, and round and round the paper which held my dinner, while I kept the latter close, and dodged and played at bopeep with it; and when at last I held still a piece of cheese between my thumb and finger, it came and nibbled it, sitting in my hand, and afterward cleaned its face and paws, like a fly, and walked away.

Walden, pp. 225–226

I am not offended by the odor of the skunk in passing by sacred places. I am invigorated rather.

Written after April 26, 1850, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 62

Whether a man’s work be hard or easy, whether he be happy or unhappy, a bird is appointed to sing to a man while he is at his work.

Written April 15, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 144

My life at this moment is like a summer morning when birds are singing.

Written February 9, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 262

Birds are the truest heralds of the seasons, since they appreciate a thousand delicate changes in the atmosphere which is their own element, of which man and the other animals cannot be aware.

Passage omitted from A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers as published in Linck C. Johnson, Thoreau’s Complex Weave, p. 472

Though I live in the woods I am not so attentive an observer of birds as I was once, but am satisfied if I get an occasional night of sound from them.

To Horatio Robinson Storer, February 15, 1847, while living at Walden, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 175

In Boston yesterday an ornithologist said significantly—“if you held the bird in your hand”—but I would rather hold it in my affections.

Written May 10, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 111

He who cuts down woods beyond a certain limit exterminates birds.

Written May 17, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 6, p. 134

The blue bird carries the sky on his back.

Written April 3, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 423

I once had a sparrow alight upon my shoulder for a moment while I was hoeing in a village garden, and I felt that I was more distinguished by that circumstance than I should have been by any epaulet I could have worn.

Walden, p. 276

I rejoice that there are owls.… They represent the stark twilight and unsatisfied thoughts which all have.

Walden, p. 124

I hear an owl hoot. How glad I am to hear him rather than the most eloquent man of the age!

Written December 25, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 378

I heard a robin in the distance, the first I had heard for many a thousand years, methought, whose note I shall not forget for many a thousand more,—the same sweet and powerful song as of yore. O the evening robin, at the end of a New England summer day!

Walden, p. 312

The first sparrow of spring! The year beginning with younger hope than ever!… What at such a time are histories, chronologies, traditions, and all written revelations?

Walden, p. 310

I hear part of a phoebe’s strain as I go over the railroad bridge—It is the voice of dying summer.

Written August 26, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 295

A man’s interest in a single blue-bird, is more than a complete, but dry, list of the fauna & flora of a town.

To Daniel Ricketson, November 22, 1858, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 528

How much more habitable a few birds make the fields! At the end of winter, when the fields are bare and there is nothing to relieve the monotony of the withered vegetation, our life seems reduced to its lowest terms. But let a bluebird come and warble over them, and what a change!

Written March 18, 1858, in his Journal, vol. X, p. 302

It is surprising that so many birds find hair enough to line their nests with. If I wish for a horse hair for my compass sights I must go to the stable but the hair bird with her sharp eyes goes to the road.

Written June 24, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 6, p. 243

If you would have the song of the sparrow inspire you a thousand years hence, let your life be in harmony with its strain to-day.

Written May 12, 1857, in his Journal, vol. IX, p. 364

As I come over the hill I hear the wood thrush singing his evening lay. This is the only bird whose note affects me like music—affects the flow & tenor of my thought—my fancy & imagination. It lifts and exhilarates me. It is inspiring. It is a medicative draught to my soul. It is an elixir to my eyes & a fountain of youth to all my senses. It changes all hours to an eternal morning.

Written June 22, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 6, pp. 235–236

What a perfectly New England sound is this voice of the crow! If you stand perfectly still anywhere in the outskirts of the town and listen, stilling the almost incessant hum of your own personal factory, this is perhaps the sound which you will be most sure to hear rising above all sounds of human industry and leading your thoughts to some far bay in the woods where the crow is venting his disgust. This bird sees the white man come and the Indian withdraw, but it withdraws not. Its untamed voice is still heard above the tinkling of the forge. It sees a race pass away, but it passes not away. It remains to remind us of aboriginal nature.

Written March 4, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, pp. 11–12

The tinkling notes of gold-finches & bobolinks which we hear now a days are of one character & peculiar to the season. They are not voluminous flowers but rather nuts of sound, ripened seeds of sound.

Written August 10, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 260

Would it not be well to carry a spy glass in order to watch these shy birds—such as ducks & hawks? In some respects methinks it would be better than a gun. The latter brings them nearer dead, but the former, alive. You can identify the species better by killing the bird because it was a dead specimen that was minutely described but you can study the habits & appearance best in the living specimen.

Written March 29, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 6, p. 48

Saw a tanager in Sleepy hollow. It most takes the eye of any bird. You here have the red-wing reversed—the deepest scarlet of the red-wing spread over the whole body—not on the wing coverts merely while the wings are black. It flies through the green foliage as if it would ignite the leaves.

Written May 20, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 6, p. 139

The thrush alone declares the immortal wealth & vigor that is in the forest.… Whenever a man hears it he is young & nature is in her spring.… He deepens the significance of all things seen in the light of his strain. He sings to make men take higher and truer views of things.

Written July 5, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 188

The strains of the aeolian harp & of the wood thrush are the truest & loft iest preachers that I know now left on this earth. I know of no missionaries to us heathen comparable to them.

Written December 31, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 7, p. 216

Who hears the fishes when they cry?

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 37

I am the wiser in respect to all knowledges, and the better qualified for all fortunes, for knowing that there is a minnow in the brook.

“Natural History of Massachusetts” in Excursions, p. 17

Go where we will, we discover infinite change in particulars only, not in generals.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 124

We are independent of the change we detect.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 128

I confess, that practically speaking, when I have learned a man’s real disposition, I have no hopes of changing it for the better or worse in this state of existence.

Walden, pp. 120–121

When my thoughts are sensible of change, I love to see and sit on rocks which I have known, and pry into their moss, and see unchangeableness so established.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 351

All change is a miracle to contemplate; but it is a miracle which is taking place every instant.

Walden, p. 11

I heard that a distinguished wise man and reformer asked him if he did not want the world to be changed; but he answered with a chuckle of surprise in his Canadian accent, not knowing that the question had ever been entertained before, “No, I like it well enough.”

On Alex Therien, the Canadian woodchopper, in Walden, p. 148

The higher the mountain on which you stand, the less change in the prospect from year to year, from age to age. Above a certain height there is no change.

To H.G.O. Blake, February 27, 1853, in Familiar Letters, pp. 210–211

With regard to essentials, I have never had occasion to change my mind.

To H.G.O. Blake, August 18, 1857, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 491

To the sick the doctors wisely recommend a change of air and scenery. Who chains me to this dull town?

“Resistance to Civil Government” in Reform Papers, p. 196

In vain I look for change abroad,

And can no difference find,

Till some new ray of peace uncalled

Illumes my inmost mind.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 295

Perhaps an instinct survives through the intensest actual love, which prevents entire abandonment and devotion, and makes the most ardent lover a little reserved. It is the anticipation of change.

“Love” in Early Essays and Miscellanies, p. 269

It will be perceived that there are two kinds of change—that of the race & that of the individual within the limits of the former.

Written June 7, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 246

Action from principle,—the perception and the performance of right,—changes things and relations; it is essentially revolutionary, and does not consist wholly with any thing which was.

“Resistance to Civil Government” in Reform Papers, p. 72

So is all change for the better, like birth and death which convulse the body.

“Resistance to Civil Government” in Reform Papers, p. 74

Though the woodchoppers have laid bare first this shore and then that, and the Irish have built their sties by it, and the railroad has infringed on its border, and the ice-men have skimmed it once, it is itself unchanged, the same water which my youthful eyes fell on; all the change is in me.

Walden, pp. 192–193

If I could convince myself that I have any right to be satisfied with men as they are, and to treat them accordingly, and not according, in some respects, to my requisitions and expectations of what they and I ought to be, then, like a good Mussulman and fatalist, I should endeavor to be satisfied with things as they are, and say it is the will of God. And, above all, there is this difference between resisting this and a purely brute or natural force, that I can resist this with some effect; but I cannot expect, like Orpheus, to change the nature of the rocks and trees and beasts.

“Resistance to Civil Government” in Reform Papers, p. 85

I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor. It is something to be able to paint a particular picture, or to carve a statue, and so to make a few objects beautiful; but it is far more glorious to carve and paint the very atmosphere and medium through which we look, which morally we can do. To affect the quality of the day, that is the highest of arts.

Walden, p. 90

Th ings do not change; we change.

Walden, p. 328

A man is not to be measured by the virtue of his described actions or the wisdom of his expressed thoughts merely, but by that free character he is, and is felt to be, under all circumstances.

“Sir Walter Raleigh” in Early Essays and Miscellanies, p. 216

We falsely attribute to men a determined character—putting together all their yesterdays and averaging them—we presume to know them. Pity the man who has a character to support.

Written April 28, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 305

The chief want, in every State that I have been into, was a high and earnest purpose in its inhabitants.

“Life without Principle” in Reform Papers, p. 177

Of what consequence, though our planet explode, if there is no character involved in the explosion?

“Life without Principle” in Reform Papers, p. 170

It is an important difference between two characters that the one is satisfied with a happy but level success but the other as constantly elevates his aim. Though my life is low, if my spirit looks upward habitually at an elevated angle it is, as it were, redeemed. When the desire to be better than we are is really sincere we are instantly elevated, and so far better already.

Written after January 10, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, pp. 177–178

Talent only indicates a depth of character in some direction.

Written February 18, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 267

Manners are conscious. Character is unconscious.

Written February 16, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 195

The Gods have given man no constant gift but the power and liberty to act greatly.

“Sir Walter Raleigh” second draft manuscript (Walden Woods Project Collection at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods)

We should make our notch every day on our characters as Robinson Crusoe on his stick. We must be at the helm at least once a day—we must feel the tiller rope in our hands, and know that if we sail, we steer.

Written February 22, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 271

I observe that the New York Herald advertises situations wanted by “respectable young women” by the column—but never by respectable young men—rather “intelligent” and “smart” ones—from which I infer that the public opinion of New York does not require young men to be respectable in the same sense in which it requires young women to be so.

Written April 30, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, pp. 211–212

Do you not feel the fruit of your spring & summer beginning to ripen, to harden its seed within you—Do not your thoughts begin to acquire consistency as well as flavor & ripeness—How can we expect a harvest of thought who have not had a seed time of character?

Written August 7, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, pp. 256–257

Men go to a fire for entertainment. When I see how eagerly men will run to a fire whether in warm or in cold weather by day or by night dragging an engine at their heels, I am astonished to perceive how good a purpose the love of excitement is made to serve. What other force pray—what offered pay—what disinterested neighborliness could ever effect so much?…

There is no old man or woman dropping into the grave but covets excitement.

Written June 5, 1850, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 81

Most men can be easily transplanted from here there, for they have so little root—no tap root—or their roots penetrate so little way that you can thrust a shovel quite under them and take them up roots and all.

Written May 14, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 58

To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates, a life of simplicity, independence, magnanimity, and trust. It is to solve some of the problems of life, not only theoretically, but practically.

Walden, pp. 14–15

How oft en are we wise as serpents without being harmless as doves.

Written February 9, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 185

It is not worth the while to let our imperfections disturb us always. The conscience really does not, and ought not to, monopolize the whole of our lives, any more than the heart or the head. It is as liable to disease as any other part. I have seen some whose consciences, owing undoubtedly to former indulgence, had grown to be as irritable as spoilt children, and at length gave them no peace.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 74

The world rests on principles.

To H.G.O. Blake, December 19, 1854, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 355

You may know what a thing costs or is worth to you; you can never know what it costs or is worth to me.

Written December 27, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, pp. 379–380

In the course of generations, however, men will excuse you for not doing as they do, if you will bring enough to pass in your own way.

Written December 27, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 380

It is insignificant & a merely negative good-fortune to be provided with thick garments against cold and wet—an unprofitable weak & defensive condition—compared with being able to extract some exhilaration—some warm Theven out of cold & wet themselves & to clothe them with our sympathy.

Written November 12, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 7, p. 156

Today I have had the experience of borrowing money for a poor Irishman who wishes to get his family to this country. One will never know his neighbors till he has carried a subscription paper among them.

Written October 12, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 7, p. 102

What is called charity is no charity but the interference of a third person.

Written February 11, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 264

To be supported by the charity of friends, or a government-pension,—provided you continue to breathe,—by whatever fine synonymes you describe these relations, is to go into the almshouse.

“Life without Principle” in Reform Papers, p. 160

Among my deeds of charity I may reckon the picking of a cherry tree for two helpless single ladies who live under the hill—but i’ faith it was robbing Peter to pay Paul—for while I was exalted in charity towards them, I had no mercy on my own stomack.

To his brother, John, July 8, 1838, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 27

You must have a genius for charity as well as for any thing else.

Walden, p. 73

The town’s poor seem to me oft en to live the most independent lives of any. May be they are simply great enough to receive without misgiving.

Walden, p. 328

I require of a visitor that he be not actually starving, though he may have the very best appetite in the world, however he got it. Objects of charity are not guests.

Walden, p. 152

I tried to help him with my experience, telling him that he was one of my nearest neighbors, and that I too, who came a-fishing here, and looked like a loafer, was getting my living like himself; that I lived in a tight light and clean house, which hardly cost more than the annual rent of such a ruin as his commonly amounts to; and how, if he chose, he might in a month or two build himself a palace of his own; that I did not use tea, nor coffee, nor butter, nor milk, nor fresh meat, and so did not have to work to get them; again, as I did not work hard, I did not have to eat hard, and it cost me but a trifle for my food; but as he began with tea, and coffee, and butter, and milk, and beef, he had to work hard to pay for them, and when he had worked hard he had to eat hard to repair the waste of his system,—and so it was as broad as it was long, indeed it was broader than it was long, for he was discontented and wasted his life into the bargain.

On John Field, Irish laborer, in Walden, p. 205

He who gives himself entirely to his fellow-men appears to them useless and selfish; but he who gives himself partially to them is pronounced a benefactor and philanthropist.

“Resistance to Civil Government” in Reform Papers, pp. 66–67

I speak for the slave when I say, that I prefer the philanthropy of Captain Brown to that philanthropy which neither shoots me nor liberates me.

“A Plea for Captain John Brown” in Reform Papers, p. 133

There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root, and it may be that he who bestows the largest amount of time and money on the needy is doing the most by his mode of life to produce that misery which he strives in vain to relieve. It is the pious slave-breeder devoting the proceeds of every tenth slave to buy a Sunday’s liberty for the rest.

Walden, pp. 75–76

I know some who in their charity give their coffee grounds to the poor!

To H.G.O. Blake, May 28, 1850, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 259

Our charitable institutions are an insult to humanity. A charity which dispenses the crumbs that fall from its overloaded tables.

Written January 28, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 299

It is our weakness that so exaggerates the virtues of philanthropy & charity & makes it the highest human attribute. The world will sooner or later tire of philanthropy and all religions based on it. They cannot long sustain my spirit.

Written April 2, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 419

There are those who have used all their arts to persuade me to undertake the support of some poor family in the town; and if I had nothing to do,—for the devil finds employment for the idle,—I might try my hand at some such pastime as that. However, when I have thought to indulge myself in this respect, and lay their Heaven under an obligation by maintaining certain poor persons in all respects as comfortably as I maintain myself, and have even ventured so far as to make them the offer, they have one and all unhesitatingly preferred to remain poor.

Walden, p. 72

I have been your pensioner for nearly two years, and still left free as under the sky. It has been as free a gift as the sun or the summer, though I have sometimes molested you with my mean acceptance of it.

To Ralph Waldo Emerson, January 24, 1843, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 78

How can I talk of Charity who at last withhold the kindness which alone makes charity desirable?

The poor want nothing less than me myself and I shirk charity by giving rags and meat.

Written March 25, 1842, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 391

I would not subtract any thing from the praise that is due to philanthropy, but merely demand justice for all who by their lives and works are a blessing to mankind.

Walden, p. 76

Shall we be charitable only to the poor?

Written after August 1, 1844, in his Journal, vol. 2, p. 117

If you should ever be betrayed into any of these philanthropies, do not let your left hand know what your right hand does, for it is not worth knowing. Rescue the drowning and tie your shoe-strings.

Walden, p. 78

All the abuses which are the object of reform with the philanthropist, the statesman, and the housekeeper, are unconsciously amended in the intercourse of Friends.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 267

Every child begins the world again.

Walden, p. 28

Children appear to me as raw as the fresh fungi on a fence rail.

Written November 7, 1839, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 85

Youth wants something to look up to—to look forward to.

Written in the summer of 1845, in his Journal, vol. 2, p. 205

How unaccountable the flow of spirits in youth. You may throw sticks and dirt into the current, and it will only rise the higher. Dam it up you may, but dry it up you may not, for you cannot reach its source. If you stop up this avenue or that, anon it will come gurgling out where you least expected, and wash away all fixtures. Youth grasps at happiness as an inalienable right.

Written September 16, 1838, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 56

The mother tells her falsehoods to her child, but thank Heaven, the child does not grow up in its parent’s shadow.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 77

How few valuable observations can we make in youth.

Written April 2, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 416

The child may soon stand face to face with the best father.

Written February 12, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 264

I am struck by the fact that the more slowly trees grow at first, the sounder they are at the core, and I think that the same is true of human beings. We do not wish to see children precocious, making great strides in their early years like sprouts, producing a soft and perishable timber, but better if they expand slowly at first, as if contending with difficulties, and so are solidified and perfected.

Written November 5, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIV, p. 217

The senses of children are unprofaned. Their whole body is one sense. They take a physical pleasure in riding on a rail. They love to teter—so does the unviolated—the unsophisticated mind derive an inexpressible pleasure from the simplest exercises of thoughts.

Written July 7, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 291

The child plays continually, if you will let it, and all its life is a sort of practical humor of a very pure kind, oft en of so fine and ethereal a nature, that its parents, its uncles and cousins, can in no wise participate in it, but must stand aloof in silent admiration, and reverence even. The more quiet the more profound it is.

“Thomas Carlyle and His Works” in Early Essays and Miscellanies, p. 237

A child loves to strike on a tin pan or other ringing vessel with a stick, because its ears being fresh sound attentive & percipient it detects the finest music in the sound at which all Nature assists. Is not the very cope of the heavens the sounding board of the infant drummer? So clear and unprejudiced ears hear the sweetest & most soul stirring melody in tinkling cow bells & the like (dogs baying the moon) not to be referred to association but intrinsic in the sound itself. Those cheap & simple sounds which men despise because their ears are dull & debauched. Ah that I were so much a child that I could unfailingly draw music from a quart pot. Its little ears tingle with the melody. To it there is music in sound alone.

Written June 9, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, pp. 82–83

The youth gets together his materials to build a bridge to the moon or perchance a palace or temple on the earth & at length the middle-aged man concludes to build a wood shed with them.

Written July 15, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 223

I suspect that the child plucks its first flower with an insight into its beauty & significance which the subsequent botanist never retains.

Written February 5, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 329

The young man is a demigod; the grown man, alas! is commonly a mere mortal.

Written December 19, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XIII, p. 35

Though the parents cannot determine whether the child shall be male or female yet methinks it depends on them whether he shall be a worthy addition to the human family.

Written November 23, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 398

The voices of school children sound like spring.

Written February 9, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 7, p. 276

Who can see these cities and say that there is any life in them?

Written in New York, September 24, 1843, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 465

Deliver me from a city built on the site of a more ancient city, whose materials are ruins, whose gardens cemeteries.

Walden, p. 264

It is folly to attempt to educate children within a city. The first step must be to remove them out of it.

Written July 25, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 332

I am more and more convinced that, with reference to any public question, it is more important to know what the country thinks of it, than what the city thinks. The city does not think much. On any moral question, I would rather have the opinion of Boxboro than of Boston and New York put together.

“Slavery in Massachusetts” in Reform Papers, pp. 98–99

What is the great attraction in cities? It is universally admitted that human beings invariably degenerate there and do not propagate their kind. Yet the prevailing tendency is to the city life, whether we move to Boston or stay in Concord.

Written fall–winter 1845–1846, in his Journal, vol. 2, p. 147

The light behind the face of the clock on the state house in Philadelphia extinguished at 11 o’clock PM with punctuality to save oil. Those hours are resigned to a few watchmen in the cities, watching for the disgrace of humanity.

Written February 1, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 315

Coming out of town—willingly as usual.

Written July 9, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 297

I don’t like the city better, the more I see of it, but worse.… It is a thousand times meaner than I could have imagined.… The pigs in the street are the most respectable part of the population. When will the world learn that a million men are of no importance compared with one man?

Written on Staten Island to Ralph Waldo Emerson, June 8, 1843, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, pp. 111–112; emended from manuscript letter (The Writings of Henry David Thoreau Manuscript Edition #247, RAR 137 Da, Kungl Biblioteket, National Library of Sweden)

Though the city is no more attractive to me than ever yet I see less difference between a city & and some dismallest swamp than formerly. It is a swamp too dismal & dreary even for me.

Written after July 29, 1850, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 97

I can forego the seeming advantages of cities without misgiving.

Written after August 8, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 359

Whoever has been down to the end of Long Wharf, and walked through Quincy Market, has seen Boston.

Cape Cod, pp. 210–211

It is well known that the chestnut timber of this vicinity has rapidly disappeared within fifteen years, having been used for railroad sleepers, for rails, and for planks, so that there is danger that this part of our forest will become extinct.

Written October 17, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIV, p. 137

The woods I walked in in my youth are cut off. Is it not time that I ceased to sing?

Written March 11, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 385

I fear that he who walks over these fields a century hence will not know the pleasure of knocking off wild apples. Ah, poor man, there are many pleasures which he will not know!

“Wild Apples” in Excursions, p. 288

I find that the rising generation in this town do not know what an oak or a pine is, having seen only inferior specimens. Shall we hire a man to lecture on botany, on oaks for instance, our noblest plants—while we permit others to cut down the few best specimens of these trees that are left? It is like teaching children Latin and Greek while we burn the books printed in those languages.

“Huckleberries,” p. 35

For beauty, give me trees with the fur on.

The Maine Woods, p. 125

We seem to think that the earth must go through the ordeal of sheep-pasturage before it is habitable by man.

The Maine Woods, p. 153

I would rather save one of these hawks than have a hundred hens and chickens. It is worth more to see them soar—especially now that they are so rare in the landscape. It is easy to buy eggs but not to buy hen-hawks. My neighbors would not hesitate to shoot the last pair of henhawks in the town to save a few of their chickens! But such economy is narrow & grovelling. It is unnecessarily to sacrifice the greater value to the less. I would rather never taste chicken’s meat nor hen’s eggs than never to see a hawk sailing through the upper air again. This sight is worth incomparably more than a chicken soup or a boiled egg.

Written June 13, 1853, in his Journal, vol. 6, pp. 197–198

By avarice and selfishness, and a grovelling habit, from which none of us is free, of regarding the soil as property, or the means of acquiring property chiefly, the landscape is deformed, husbandry is degraded with us, and the farmer leads the meanest of lives. He knows Nature but as a robber.

Walden, pp. 165–166

Why should not we, who have renounced the king’s authority, have our national preserves, where no villages need be destroyed, in which the bear and panther, and some even of the hunter race, may still exist, and not be “civilized off the face of the earth,”—our forests, not to hold the king’s game merely, but to hold and preserve the king himself also, the lord of creation,—not for idle sport or food, but for inspiration and our own true recreation?

The Maine Woods, p. 156

The very willow-rows lopped every three years for fuel or powder,—and every sizable pine and oak, or other forest tree, cut down within the memory of man! As if individual speculators were to be allowed to export the clouds out of the sky, or the stars out of the firmament, one by one. We shall be reduced to gnaw the very crust of the earth for nutriment.

The Maine Woods, p. 154

Strange that so few ever come to the woods to see how the pine lives and grows and spires, lifting its evergreen arms to the light,—to see its perfect success, but most are content to behold it in the shape of many broad boards brought to market, and deem that its true success! But the pine is no more lumber than man is, and to be made into boards and houses is no more its true and highest use than the truest use of a man is to be cut down and made into manure. There is a higher law affecting our relation to pines as well as to men. A pine cut down, a dead pine, is no more a pine than a dead human carcass is a man.

The Maine Woods, p. 121

Men & boys are learning all kinds of trades but how to make men of themselves. They learn to make houses, but they are not so well housed, they are not so contented in their houses, as the woodchucks in their holes. What is the use of a house if you haven’t got a tolerable planet to put it on?

To H.G.O. Blake, May 20, 1860, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, pp. 578–579

What are the natural features which make a township handsome? A river, with its waterfalls and meadows, a lake, a hill, a cliffor individual rocks, a forest, and ancient trees standing singly. Such things are beautiful; they have a high use which dollars and cents never represent. If the inhabitants of a town were wise, they would seek to preserve these things, though at a considerable expense; for such things educate far more than any hired teachers or preachers, or any at present recognized system of school education.

Written January 3, 1861, in his Journal, vol. XIV, p. 304

Each town should have a park, or rather a primitive forest of five hundred or a thousand acres, where a stick should never be cut for fuel, a common possession forever, for instruction and recreation. We hear of cow-common and ministerial lots, but we want men-commons and lay lots, inalienable forever. Let us keep the New World new, preserve all the advantages of living in the country. There is meadow and pasture and wood-lot for the town’s poor. Why not a forest and huckleberry-field for the town’s rich? All Walden Wood might have been preserved for our park forever, with Walden in its midst, and the Easterbrooks Country, an unoccupied area of some four square miles, might have been our huckleberry-field.

Written October 15, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 387

But most men, it seems to me, do not care for Nature and would sell their share in all her beauty, as long as they may live, for a stated sum—many for a glass of rum. Thank God, men cannot as yet fly, and lay waste the sky as well as the earth! We are safe on that side for the present.

Written January 3, 1861, in his Journal, vol. XIV, pp. 306–307

If some are prosecuted for abusing children, others deserve to be prosecuted for maltreating the face of nature committed to their care.

Written September 28, 1857, in his Journal, vol. X, p. 51

As some give to Harvard College or another institution, why might not another give a forest or huckleberry-field to Concord? A town is an institution which deserves to be remembered. We boast of our system of education, but why stop at schoolmasters and schoolhouses? We are all schoolmasters, and our schoolhouse is the universe. To attend chiefly to the desk or schoolhouse while we neglect the scenery in which it is placed is to save at the spile and waste at the bung. If we do not look out we shall find our fair schoolhouse standing in a cow-yard at last.

Written October 15, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 387; emended from manuscript Journal (MA 1302, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York)

It would be worth the while if in each town there were a committee appointed to see that the beauty of the town received no detriment. If we have the largest boulder in the county, then it should not belong to an individual, nor be made into door-steps.

Written January 3, 1861, in his Journal, vol. XIV, pp. 304–305

We accuse savages of worshipping only the bad spirit, or devil, though they may distinguish both a good and a bad; but they regard only that one which they fear and worship the devil only. We too are savages in this, doing precisely the same thing. This occurred to me yesterday as I sat in the woods admiring the beauty of a blue butterfly. We are not chiefly interested in birds and insects, for example, as they are ornamental to the earth and cheering to man, but we spare the lives of the former only on condition that they eat more grubs than they do cherries.

Written May 1, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 170; emended from manuscript Journal (MA 1302, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York)

The catechism says that the chief end of man is to glorify God and enjoy him forever, which of course is applicable mainly to God as seen in his works. Yet the only account of its beautiful insects—butterflies, etc.—which God has made and set before us which the State ever thinks of spending any money on is the account of those which are injurious to vegetation! This is the way we glorify God and enjoy him forever. Come out here and behold a thousand painted butterflies and other beautiful insects which people the air, then go to the libraries and see what kind of prayer and glorification of God is there recorded. Massachusetts has published her report on “Insects Injurious to Vegetation,” and our neighbor the “Noxious Insects of New York.” We have attended to the evil and said nothing about the good.

Written May 1, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, pp. 170–171

Children are attracted by the beauty of butterflies, but their parents and legislators deem it an idle pursuit. The parents remind me of the Devil, not the children of God. Though God may have pronounced his work good, we ask. “Is it not poisonous?”

Written May 1, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 171; emended from manuscript Journal (MA 1302, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York)

I thought with regret how soon these trees, like the black birches that grew on the hill near by, would be all cut off, and there would be almost nothing of the old Concord left, and we should be reduced to read old deeds in order to be reminded of such things,—deeds, at least, in which some old and revered bound trees are mentioned. These will be the only proof at last that they ever existed.

Written November 8, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 299

The bream appreciated floats in the pond as the centre of the system, another image of God. Its life no man can explain more than he can his own. I want you to perceive the mystery of the bream. I have a contemporary in Walden. It has fins where I have legs and arms. I have a friend among the fishes, at least a new acquaintance.… Acquaintance with it is to make my life more rich and eventful.

Written November 30, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 359; emended from manuscript Journal (MA 1302, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York)

When the question of the protection of birds comes up, the legislatures regard only a low use and never a high use; the best-disposed legislators employ one, perchance, only to examine their crops and see how many gnats or cherries they contain, and never to study their dispositions, or the beauty of their plumage, or listen and report on the sweetness of their song. The legislature will preserve a bird professedly not because it is a beautiful creature, but because it is a good scavenger or the like. This, at least, is the defence setup. It is as if the question were whether some celebrated singer of the human race—some Jenny Lind or another—did more harm or good, should be destroyed, or not, and therefore a committee should be appointed, not to listen to her singing at all, but to examine the contents of her stomach and see if she devoured anything which was injurious to the farmers and gardeners, or which they cannot spare.

Written April 8, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, pp. 124–125; emended from manuscript Journal (MA 1302, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York)

In my boating of late I have several times scared up a couple of summer ducks of this year, bred in our meadows. They allowed me to come quite near, and helped to people the river. I have not seen them for some days. Would you know the end of our intercourse? Goodwin shot them, and Mrs.———, who never sailed on the river ate them. Of course, she knows not what she did.… They belonged to me, as much as to anyone, when they were alive, but it was considered of more importance that Mrs.———should taste the flavor of them dead than that I should enjoy the beauty of them alive.

Written August 16, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 107; emended from manuscript Journal (MA 1302, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York)

We have heard much of the wonderful intelligence of the beaver, but that regard for the beaver is all a pretense, and we would give more for a beaver hat than to preserve the intelligence of the whole race of beavers.

Written April 8, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 121

The smokes from a dozen clearings far and wide, from a portion of the earth thirty miles or more in diameter, reveal the employment of many husbandmen at this season. Thus I see the woods burned up from year to year. The telltale smokes reveal it. The smokes will become rarer and thinner year by year, till I shall detect only a mere feathery film and there is no more brush to be burned.

Written October 10, 1857, in his Journal, vol. X, p. 83

The Anglo American can indeed cut down and grub up all this waving forest and make a stump speech and vote for Buchanan on its ruins, but he cannot converse with the spirit of the tree he fells—he cannot read the poetry and mythology which retire as he advances. He ignorantly erases mythological tablets in order to print his handbills and town meeting warrants on them.

The Maine Woods, p. 229

I seek acquaintance with Nature,—to know her moods and manners. Primitive Nature is the most interesting to me. I take infinite pains to know all the phenomena of the spring, for instance, thinking that I have here the entire poem, and then, to my chagrin, I learn that it is but an imperfect copy that I possess and have read, that my ancestors have torn out many of the first leaves and grandest passages, and mutilated it in many places. I should not like to think that some demigod had come before me and picked out some of the best of the stars. I wish to know an entire heaven and an entire earth.

Written March 23, 1856, in his Journal, vol. VIII, p. 221; emended from manuscript Journal (MA 1302, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York)

I am thinking by what long discipline and at what cost a man learns to speak simply at last.

Written December 12, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 202

Written February 20, 1842, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 369

Say what you have to say, not what you ought.

Walden, p. 327

The most constant phenomenon when men or women come together is talking.

Written between 1842 and 1844, in his Journal, vol. 2, p. 67

All words are gossip.

Written between 1847 and 1848, in his Journal, vol. 2, p. 380

Men cannot stay long together without talking, according to the rules of polite society.

Written between 1842 and 1844, in his Journal, vol. 2, p. 67

We had nothing to say to one another, and therefore we said a great deal!

To Ralph Waldo Emerson, January 24, 1843, after meeting John L. O’Sullivan, founder and editor of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 77

Surface meets surface. When our life ceases to be inward and private, conversation degenerates into mere gossip.

“Life without Principle” in Reform Papers, p. 169

I have sometimes heard a conversation beginning again when it should have ceased for want of fuel.

Passage omitted from A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers as published in Linck C. Johnson, Thoreau’s Complex Weave, p. 468

The gregariousness of men is their most contemptible and discouraging aspect.

Written April 3, 1858, in his Journal, vol. X, p. 350

We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate. Either is in such a predicament as the man who was earnest to be introduced to a distinguished deaf woman, but when he was presented, and one end of her ear trumpet was put into his hand, had nothing to say.

Walden, p. 52

Do not speak for other men—Speak for yourself.

Written December 25, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 223

In the morning we do not believe in expediency—we will start afresh, and have no patching—no temporary fixtures. The afternoon man has an interest in the past; his eye is divided and he sees indifferently well either way.

Written April 4, 1839, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 69

For my panacea… let me have a draught of undiluted morning air. Morning air! If men will not drink of this at the fountain-head of the day, why, then, we must even bottle up some and sell it in the shops, for the benefit of those who have lost their subscription ticket to morning time in this world.

Walden, p. 138

Have you knowledge of the morning? Do you sympathise with that season of nature? Are you abroad early, brushing the dews aside? If the sun rises on you slumbering, if you do not hear the morning cock crow, if you do not witness the blushes of Aurora, if you are not acquainted with Venus as the morning star, what relation have you to wisdom & purity? You have then forgotten your creator in the days of your youth.

Written July 18, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 312

Morning brings back the heroic ages.

Walden p. 88

Morning is when I am awake and there is a dawn in me.

Walden, p. 90

The day is an epitome of the year. The night is the winter, the morning and evening are the spring and fall, and the noon is the summer.

Walden, p. 301

Many men walk by day, few walk by night. It is a very different season.

Written after July 1, 1850, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 92

Is not the midnight like central Africa to most?

Written February 1, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 315

To see the sun rise or go down every day would preserve us sane forever—so to relate ourselves for our mind’s & body’s health to a universal fact.

Written January 20, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 270

It is day & we have more of that same light that the moon sent us but not reflected now but shining directly. The sun is a fuller moon. Who knows how much brighter day there may be?

Written June 11, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 92

The voice of the crickets heard at noon from deep in the grass allies day to night. It is unaffected by sun & moon. It is a mid-night sound heard at noon—a midday sound heard at midnight.

Written June 29, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 280

The morning hope is soon lost in what becomes the routine of the day & we do not recover ourselves again until we land on the pensive shores of evening.

Written January 8, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 7, p. 227

How swift ly the earth appears to revolve at sunset which at midday appears to rest on its axle.

Written December 21, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 215

We never tire of the drama of sunset.… Can Washington Street or Broad-Way show anything as good? Every day a new picture is painted and framed, held up for half an hour in such lights as the great artist chooses & then withdrawn & the curtain falls.

Written January 7, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 242

The man is blessed who every day is permitted to behold anything so pure & serene as the western sky at sunset while revolutions vex the world.

Written December 27, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 225

If I were to choose a time for a friend to make a passing visit to this world for the first time in the full possession of all his faculties perchance it would be at a moment when the sun was setting with splendor in the west—his light reflected far & wide through the clarified air after a rain—and a brilliant rain-bow as now oerarching the eastern sky.

Written August 7, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 287

Every sunset which I witness inspires me with the desire to go to a west as distant and as fair as that into which the Sun goes down.

“Walking” in Excursions, p. 197

So is not shade as good as sunshine—night as day? Why be eagles and thrushes always, and owls and whippoor-wills never?

Written June 16, 1840, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 129

As the twilight deepens and the moonlight is more & more bright I begin to distinguish myself, who I am & where. As my walls contract I become more collected & composed & sensible of my own existence—as when a lamp is brought into a dark apartment & I see who the company are.

Written August 5, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, pp. 353–354

By moonlight all is simple. We are enabled to erect ourselves, our minds, on account of the fewness of objects. We are no longer distracted. It is simple as bread and water. It is simple as the rudiments of an art.

Written September 22, 1854, in his Journal, vol. VII, p. 51

Nature seems not have designed that man should be much abroad by night and in the moon proportioned the light fitly. By the faintness & rareness of the light compared with that of the sun she expresses her intention with regard to him.

Written June 14, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 269

When man is asleep & day fairly forgotten, then is the beauty of moon light seen over lonely pastures where cattle are silently feeding.

Written June 14, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 268

The night is oracular.

Written October 27, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 156

There is a certain glory attends on water by night. By it the heavens are related to the earth—Undistinguishable from a sky beneath you.

Written June 13, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 260

When I am outside on the outskirts of the town enjoying the still majesty of the moon I am wont to think that all men are aware of this miracle—that they too are silently worshipping this manifestation of divinity elsewhere—but when I go into the house I am undeceived, they are absorbed in checquers or chess or novel, though they may have been advertised of the brightness through the shutters.

Written May 16, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 219

We know but few men, a great many coats and breeches.

Walden, p. 22

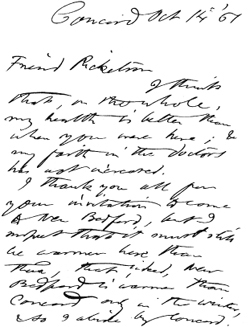

FIG. 3. Edward Emerson’s copy of Daniel Ricketson’s pencil sketch of Thoreau originally drawn on December 12, 1854. The Raymond Adams Collection (The Thoreau Society® Collections at the Thoreau Institute). Courtesy of the Thoreau Society.

No man ever stood the lower in my estimation for having a patch in his clothes.

Walden, p. 22

It is highly important to invent a dress which will enable us to be abroad with impunity in the severest storms. We cannot be said to have fully invented clothing yet.

Written April 22, 1856, in his Journal, vol. VIII, pp. 299–300

I say, beware of all enterprises that require new clothes, and not rather a new wearer of clothes.

Walden, p. 23

We worship not the Graces, nor the Parcae, but Fashion. She spins and weaves and cuts with full authority. The head monkey at Paris puts on a traveller’s cap, and all the monkeys in America do the same.

Walden, p. 25

When I see a fine lady or gentleman dressed to the top of the fashion, I wonder what they would do if an earthquake should happen, or a fire suddenly break out, for they seem to have counted only on fair weather, and that things will go on smoothly and without jostling.

Written July 12, 1840, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 157

The walker and naturalist does not wear a hat, or a shoe, or a coat, to be looked at, but for other uses. When a citizen comes to take a walk with me I commonly find that he is lame,—disabled by his shoeing. He is sure to wet his feet, tear his coat, and jam his hat, and the superior qualities of my boots, coat, and hat appear. I once went into the woods with a party for a fortnight. I wore my old and common clothes, which were of Vermont gray. They wore, no doubt, the best they had for such an occasion,—of a fashionable color and quality. I thought that they were a little ashamed of me while we were in the towns. They all tore their clothes badly but myself, and I, who, it chanced, was the only one provided with needles and thread, enabled them to mend them. When we came out of the woods I was the best dressed of any of them.

Written March 26, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIII, pp. 231–232

How different are men and women, e.g. in respect to the adornment of their heads! Do you ever see an old or jammed bonnet on the head of a woman at a public meeting? But look at any assembly of men with their hats on; how large a proportion of the hats will be old, weather-beaten, and indented, but I think so much the more picturesque and interesting!

Written December 25, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XIII, p. 51

The chief recommendation of the Kossuth hat is that it looks old to start with, and almost as good as new to end with.

Written December 25, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XIII, p. 52

It is generally conceded that a man does not look the worse for a somewhat dilapidated hat.

Written December 25, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XIII, p. 52

Men wear their hats for use; women theirs for ornament.

Written December 25, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XIII, p. 52

Ladies are in haste to dress as if it were cold or as if it were warm,—though it may not yet be so,—merely to display a new dress.

Written December 25, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XIII, p. 52

It is astonishing how far a merely well-dressed and good-looking man may go without being challenged by any sentinel.

Written January 3, 1856, in his Journal, vol. VIII, p. 82

Every day our garments become more assimilated to ourselves, receiving the impress of the wearer’s character, until we hesitate to lay them aside, without such delay and medical appliances and some such solemnity even as our bodies.

Walden, pp. 21–22

I have had made a pair of corduroy pants, which cost when done $1.60. They are of that peculiar clay-color, reflecting the light from portions of their surface. They have this advantage, that, beside being very strong, they will look about as well three months hence as now,—or as ill, some would say.

Written May 8, 1857, in his Journal, vol. IX, p. 359

When I go a-visiting I find that I go off the fashionable street—not being inclined to change my dress—to where man meets man and not polished shoe meets shoe.

Written June 11, 1855, in his Journal, vol. VII, p. 416

I have just got a letter from Ricketson, urging me to come to New Bedford, which possibly I may do. He says I can wear my old clothes there.

To H.G.O. Blake, September 26, 1855, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 385

I just had a coat come home from the tailors—ah me—who am I that I should wear this coat? It was fitted upon one of the Devil’s angels about my size. Of what use that measuring of me if he did not measure my character? This is not the figure that I cut—this is the figure the tailor cuts.

Written January 14, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 7, p. 241

I was pleased the other day to see a son of Concord return after an absence of eight years, not in a shining suit of black, with polished boots and a beaver or silk hat, as if on a furlough from human duties generally,—a mere clothes-horse,—but clad in an honest clay-colored suit and a snug every-day cap. It showed unusual manhood.

Written May 8, 1857, in his Journal, vol. IX, pp. 359–360

I would make education a pleasant thing both to the teacher and the scholar. This discipline, which we allow to be the end of life, should not be one thing in the schoolroom, and another in the street. We should seek to be fellow students with the pupil, and we should learn of, as well as with him, if we would be most helpful to him.

To Orestes Brownson, December 30, 1837, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 20

Which would have advanced the most at the end of a month,—the boy who had made his own jackknife from the ore which he had dug and smelted, reading as much as would be necessary for this,—or the boy who had attended the lectures on metallurgy at the Institute in the mean while, and had received a Rodgers’ penknife from his father?

Walden, p. 51

I served my apprenticeship and have since done considerable journeywork in the huckleberry field. Though I never paid for my schooling and clothing in that way, it was some of the best schooling that I got and paid for itself.

“Huckleberries,” p. 26

FIG. 4. Letter of recommendation for Thoreau as a teacher from Josiah Quincy, president of Harvard University, March 26, 1838. The Raymond Adams Collection (The Thoreau Society® Collections at the Thoreau Institute). Courtesy of the Thoreau Society

Knowledge does not come to us by details but by lieferungs from the gods.

Written July 7, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 291

Knowledge does not come to us by details, but in flashes of light from heaven.

“Life without Principle” in Reform Papers, p. 173

What we do best or most perfectly is what we have most thoroughly learned by the longest practice, and at length it falls from us without our notice, as a leaf from a tree.

Written March 11, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 39

We saw one school-house in our walk, and listened to the sounds which issued from it; but it appeared like a place where the process, not of enlightening, but of obfuscating the mind was going on, and the pupils received only so much light as could penetrate the shadow of the Catholic church.

“A Yankee in Canada” in Excursions, p. 116

Knowledge is to be acquired only by a corresponding experience. How can we know what we are told merely? Each man can interpret another’s experience only by his own.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 365

I have noticed that whatever is thought to be covered by the word education—whether reading, writing or ’rithmetick—is a great thing, but almost all that constitutes education is a little thing in the estimation of such speakers as I refer to.

“Huckleberries,” p. 3

Those things for which the most money is demanded are never the things which the student most wants. Tuition, for instance, is an important item in the term bill, while for the far more valuable education which he gets by associating with the most cultivated of his contemporaries no charge is made.

Walden, p. 50

The audience are never tired of hearing how far the wind carried some man woman or child—or family bible—but they are immediately tired if you undertake to give them a scientific account of it.

Written February 4, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 328

All the branches and none of the roots.

On hearing Emerson remark that most of the branches of knowledge were taught at Harvard, as reported by John Albee in Remembrances of Emerson, p. 30

We spend more on almost any article of bodily aliment or ailment than on our mental aliment.

Walden, p. 108

It is time that we had uncommon schools, that we did not leave off our education when we begin to be men and women. It is time that villages were universities, and their elder inhabitants the fellows of universities, with leisure—if they are indeed so well off—to pursue liberal studies the rest of their lives.

Walden, pp. 108–109

I have never declined paying the highway tax, because I am as desirous of being a good neighbor as I am of being a bad subject; and, as for supporting schools, I am doing my part to educate my fellow-countrymen now.

On spending a night in jail for nonpayment of taxes in “Resistance to Civil Government” in Reform Papers, p. 84

Men have a respect for scholarship and learning greatly out of proportion to the use they commonly serve.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 105

What does education oft en do! It makes a straight-cut ditch of a free meandering brook.

Written after October 31, 1850, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 130

Many College text books which were a weariness & a stumbling block when studied I have since read a little in with pleasure & profit.

Written February 19, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 10

During the berry season the Schools have a vacation and many little fingers are busy picking these small fruits.… I remember how glad I was when I was kept from school a half a day to pick huckleberries on a neighboring hill all by myself to make a pudding for the family dinner. Ah, they got nothing but the pudding—but I got invaluable experience beside.

Written July 16, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 307

I well remember with what a sense of freedom and spirit of adventure I used to take my way across the fields with my pail… toward some distant hill or swamp, when dismissed for all day, and I would not now exchange such an expansion of all my being for all the learning in the world. Liberation and enlargement—such is the fruit which all culture aims to secure. I suddenly knew more about my books than if I had never ceased studying them. I found myself in a schoolroom where I could not fail to see and hear things worth seeing and hearing—where I could not help getting my lesson—for my lesson came to me. Such experience oft en repeated, was the chief encouragement to go to the Academy and study a book at last.

“Huckleberries,” pp. 27–28

Do not think that the fruits of New England are mean and insignificant, while those of some foreign land are noble and memorable. Our own, whatever they may be, are far more important to us than any others can be. They educate us, and fit us to live in New England. Better for us is the wild strawberry than the pineapple, the wild apple than the orange, the hazelnut or pignut than the cocoanut or almond, and not on account of their flavor merely, but the part they play in our education.

Written November 26, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIV, p. 274

It is strange that men are in such haste to get fame as teachers rather than knowledge as learners.

Written March 11, 1856, in his Journal, vol. VIII, p. 205

Who knows whence his education is to come!

To Isaac Hecker, after August 15, 1844, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 158

I am still a learner, not a teacher, feeding somewhat omnivorously, browsing both stalk & leaves.

To H.G.O. Blake, May 21, 1856, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, pp. 423–424

We of Massachusetts boast a good deal of what we do for the education of our people—of our district-school system—& yet our district schools are as it were but infant schools & we have no system for the education of the great mass who are grown up.

Written September 27, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 101

We boast that we belong to the 19th century and are making the most rapid strides of any nation. But consider how little this village does for its own culture—perchance a comparatively decent system of common schools—schools for infants only, as it were, but excepting the half starved lyceum in the winter, no school for ourselves.

Written August 29, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 5, p. 318

With a little more deliberation in the choice of their pursuits, all men would perhaps become essentially students and observers, for certainly their nature and destiny are interesting to all alike.

Walden, p. 99

The poet says the proper study of mankind is man. I say study to forget all that—take wider views of the universe.

Written April 2, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 418

The universe is wider than our views of it.

Walden, p. 320

It is only when we forget all our learning that we begin to know.

Written October 4, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 371

What is hope, what is expectation, but a seed-time whose harvest cannot fail, an irresistible expedition of the mind, at length to be victorious?

Written February 20, 1857, in his Journal, vol. IX, p. 275

Fishermen, hunters, woodchoppers, and others, spending their lives in the fields and woods, in a peculiar sense a part of Nature themselves, are oft en in a more favorable mood for observing her, in the intervals of their pursuits, than philosophers or poets even, who approach her with expectation.

Walden, p. 210

What is this heaven which they expect, if it is no better than they expect? Are they prepared for a better than they can now imagine?

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 379

Consider the infinite promise of a man, so that the sight of his roof at a distance suggests an idyll or pastoral, or of his grave an Elegy in a Country Churchyard.

Written October 3, 1859, in his Journal, vol. XII, p. 369

Most men can keep a horse or keep up a certain fashionable style of living, but few indeed can keep up great expectations.

Written May 6, 1858, in his Journal, vol. X, p. 405

Can I not by expectation affect the revolutions of nature—make a day to bring forth something new?

Written April 18, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 468

We soon get through with Nature. She excites an expectation which she cannot satisfy. The merest child which has rambled into a copse wood dreams of a wilderness so wild and strange & inexhaustible as Nature can never show him.

Written May 23, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 146

Give me the old familiar walk, post-office and all, with this ever new self, with this infinite expectation and faith, which does not know when it is beaten. We’ll go nutting once more. We’ll pluck the nut of the world, and crack it in the winter evenings. Theatres and all other sightseeing are puppet-shows in comparison.

Written November 1, 1858, in his Journal, vol. XI, p. 274

The truest account of heaven is the fairest & I will accept none which disappoints expectation. It is more glorious to expect a better, than to enjoy a worse.

Written January 26, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 290

We must learn to reawaken and keep ourselves awake, not by mechanical aids, but by an infinite expectation of the dawn, which does not forsake us in our soundest sleep.

Walden, p. 90

We may well be ashamed to tell what things we have read or heard in our day. I do not know why my news should be so trivial,—considering what one’s dreams and expectations are, why the developments should be so paltry.

“Life without Principle,” in Reform Papers, p. 170

With what infinite & unwearied expectation and proclamations the cocks usher in every dawn as if there had never been one before.

Written March 16, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 391

Show men unlimited faith as the coin with which you will deal with them, and they will invariably exhibit the best wares they have.

Written January 28, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 233

May I go to my slumbers as expecting to arise to a new & more perfect day.

Written July 16, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 311

Expectation may amount to prophecy.

Written April 2, 1852, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 415

Our circumstances answer to our expectations and the demand of our natures.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 292

Is not the attitude of expectation somewhat divine?—a sort of home-made divineness?

To H.G.O. Blake, May 28, 1850, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 259

They who are ready to go are already invited.

Written July 2, 1840, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 147

Who is old enough to have learned from experience?

Written March 21, 1842, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 385

My only integral experience is in my vision.

To H.G.O. Blake, May 2, 1848, in The Correspondence of Henry David Thoreau, p. 222

All we have experienced is so much gone within us and there lies. It is the company we keep.

Written February 8, 1841, in his Journal, vol. 1, p. 258

In the summer we lay up a stock of experiences for the winter, as the squirrel of nuts. Something for conversation in winter evenings.

Written September 4, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 40

Surely one may as profitably be soaked in the juices of a swamp for one day as pick his way dry-shod over sand. Cold and damp,—are they not as rich experience as warmth and dryness?

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 300

Going a-berrying implies more things than eating the berries.

“Huckleberries,” pp. 26–27

The poet deals with his privatest experience.

Written April 8, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 57

It is a grand fact that you cannot make the fairer fruits or parts of fruits matter of commerce; that is, you cannot buy the highest use and enjoyment of them. You cannot buy that pleasure which it yields to him who truly plucks it.

Wild Fruits, p. 5

The chief want is ever a life of deep experiences.

Written June 8, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 181

Our mother’s faith has not grown with her experience. Her experience has been too much for her. The lesson of life was too hard for her to learn.

A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, p. 77

Methinks my present experience is nothing, my past experience is all in all. I think that no experience which I have today comes up to or is comparable with the experiences of my boyhood.

Written July 16, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 305

Our life is not altogether a forgetting but also alas to a great extent a remembering of that which perchance we should never have been conscious of—the consciousness of what should not be permitted to disturb a man’s waking hours.

Written November 10, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 4, p. 174

The value of any experience is measured, of course, not by the amount of money, but the amount of development we get out of it.

Written November 26, 1860, in his Journal, vol. XIV, p. 274

Do not tread on the heels of your experience. Be impressed without making a minute of it.

Written July 23, 1851, in his Journal, vol. 3, p. 331

There is no such thing as pure objective observation. Your observation to be interesting i.e. to be significant must be subjective.

Written May 6, 1854, in his Journal, vol. 8, p. 98

Early for several mornings I have heard the sound of a flail. It leads me to ask if I have spent as industrious a spring & summer as the farmer & gathered as rich a crop of experience. Let the sound of my flail be heard, by those who have ears to hear, separating the kernel from the chaff all the fall & winter & a sound no less cheering it will be.