The Allied victory in World War II placed part of Germany and all of Eastern Europe into the hands of the Soviet Union. By 1947, the Iron Curtain had fallen across Europe, dividing it into democratic and Communist nations. For the next 50 years, the Cold War mentality underscored how nations did business.

The Cold War created a sense of anxiety among Americans, despite the country’s booming economy and status as the leading nation of the Free World. Even as Americans feared a nuclear war with the “Reds,” the United States made giant strides in war technology, developing B-52s and missiles to carry hydrogen bombs to wipe out enemy targets. The Soviets did the same.

A rabidly anti-Communist senator, Joseph McCarthy, was trying to convince the public that “Commies” were destroying the American way of life and conducted hearings that appeared on television. Children in schools practiced air-raid drills and crawled under their desks. The United States and the USSR embarked on a space race after Russia launched the first satellite into orbit in 1957. Overseas, the United States tasked its military and the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) with ensuring that other nations, large and small, stay in line with the Free World.

The Cold War never turned hot between the United States and Soviet Russia, but the two nations equipped and financed small wars and revolutions in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. When the Cuban Revolution put Fidel Castro in power in 1959, it soon became clear that Communists had a foothold in the Americas. Castro’s presence in Cuba seemed to signal imminent revolution all across Latin America and the Caribbean, and for the next 25 years, the United States bolstered anti-Communist governments, regimes that nonetheless were decidedly nondemocratic.

With China under the control of its Communist rulers by 1949, the US government feared that all of East Asia could also go “red.” When Communist North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950, the United States rushed to aid the South and fought an undeclared war against North Korea and China. At the US Department of Defense, a theory in foreign policy began to take hold: that once a small country succumbed to Communist rule, its neighbors would fall like a series of dominoes. This domino theory became the operating principle for American foreign policy during the Cold War years in the 1950s and ’60s, driving the buildup of US forces to fight the Vietnam War.

Then suddenly, for the first time in the war, I experienced the cold, awful certainty that there was no escape. My reactions were trite. As with most people who suddenly accept death as inevitable and imminent, I was simply filled with surprise that this was finally going to happen to me.—Marguerite Higgins

Sometimes the men and women who report the news become news themselves. Celebrity journalists are nothing new in American culture; Elizabeth Cochrane, aka Nellie Bly, captured readers’ imaginations in 1889 with her globetrotting exploits, and Peggy Hull drew quite a following as the girl reporter “who got to Paris.” But none rose faster nor further than Marguerite Higgins, a war correspondent for the New York Herald Tribune, when she went to Korea to report on the Chinese invasion in June 1950, which won her a Pulitzer Prize for international reporting in 1951. Her friend Carl Mydans, a prominent Life magazine photographer, shot a series of pictures and wrote a flattering article that Life ran in a six-page spread on October 2, 1950. Marguerite Higgins became a national sensation.

Mydans’s story neatly summed up how Maggie was “engaged in three separate campaigns” in Korea: one to report on the war; the second, her famous feud with fellow Herald Tribune reporter Homer Bigart; and the third, “ever to deny that sex has anything to do with war correspondence.” In fact, Maggie’s dear friend (and defender) was spot on about her life as a war reporter, and biographers and students of American history and culture have wrangled over the details of her life ever since.

Marguerite Higgins seemed to know what she wanted from life. She cultivated an air of cool detachment, though she claimed to have deep doubts about how she measured up against everyone else. Born in Hong Kong in 1920 to an American father and French mother, she grew up speaking a mix of languages and was teased about her accent when her family moved to Oakland, California. Her father, Lawrence Higgins, like so many well-heeled businessmen, lost his job as a stockbroker when the stock market crashed in October 1929. Though he found other work, Marguerite’s dissolute father succumbed to alcoholism that put a strain on his family. Maggie’s mother, Marguerite Goddard Higgins, got a job teaching French at a tony girls’ school where her daughter could attend tuition-free.

Marguerite’s father resented the life that the Depression had doled out to him, complaining about the “flabby routine of his petite bourgeois life in Oakland, California,” to use his wife’s French words for the lower middle class. He spoke to his daughter of his heroic past during World War I, first as an ambulance driver and later as a pilot, and pointedly raised his daughter to fear nothing and no one. Years later, after Maggie had made a splash as a war correspondent, he told a Time interviewer that he raised Maggie so “that she should always be able to stand on her own feet.” Then Lawrence Higgins said something else:

Marguerite is not so much competitive, as she is a perfectionist. There was only one place for Marguerite and that was the top, regardless as of what she was doing … learning to swim, to play the violin, or whatever she went into. But it was strictly for her own satisfaction, not to beat somebody else out.

From the girls’ school, Maggie went to college at the University of California at Berkeley. She joined a sorority, where she must have shocked a few sisters when she stated she believed in free love. But on large parts of Berkeley’s campus, the “petite bourgeois” attitudes of Oakland didn’t fly. Her interests turned to working for the campus paper, the Daily Californian. Big ideas were always churning at Berkeley, and Maggie met students and professors who didn’t share the same values as her neighbors at home. She mingled with liberals and Socialists who dreamed about a new and different order to American society, and she dated a Communist, a philosophy student named Stanley Moore who was studying for a doctorate.

For a time Maggie worked as a cub reporter for a small-town paper, but the promise of working in big-time journalism lured her to the master’s program at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism in New York. Only 12 slots were open to women when Maggie applied, and she scrambled to get a spot just four days before classes began in the fall of 1941. Off to New York Maggie went, rooming with an artist in Greenwich Village, where bohemian culture flourished.

While she attended grad school, Maggie worked as a stringer for the New York Herald Tribune, then a leading city paper and fierce competitor against the New York Times. She dug around Columbia’s campus for stories and submitted them to the Herald Tribune, which paid her only for the ones they accepted. At some point during her studies she announced that she planned to become more famous than Dorothy Thompson, then the nation’s leading female journalist.

Maggie’s talent for digging out news got her a full-time job at the Herald Tribune after she graduated in 1942, and she began the typical climb up the reporter’s ladder—first on general assignments, next on district news, then the graveyard shift reporting on crime and fires, then to the rewrite desk, and finally to the top as a features writer. Maggie never did become a top-notch writer among American journalists, but several old-timers noticed that no one could equal her skill at getting news, including fresh angles to old stories.

It was a man’s world in the city room at the New York Herald Tribune, even if a handful of women like Maggie Higgins worked there. After hours, a reporter was likely to stroll down the street to the Artists and Writers Restaurant, affectionately called “Bleecks” (pronounced “Blake’s”) after its owner. Over drinks at the bar or in the back room, newspapermen talked shop and tossed around ideas, much as executives and managers at New York’s banks and corporate headquarters gathered in their private dining rooms for drinks and lunch. Maggie Higgins wasn’t welcome in that back room, as women in general were excluded from these sacred male watering holes where they talked shop and made important decisions. Maggie may have considered herself as competent as any male reporter and entitled to the same information, but in the 1940s, most men didn’t see things that way.

Controversy and gossip followed Maggie Higgins from her college years onward. Her outward appearance—bright blue eyes, tall, athletic figure, and curly blond hair—could easily have attracted others. But the simple truth was that most people, women or men, didn’t like Marguerite Higgins. Her single-mindedness and her need for perfection worked against her. But Maggie didn’t care what other people thought. Her raw ambition made her few friends and many enemies. Soon enough, the gossip began: that she stole colleagues’ stories and that she slept with sources, editors, and other reporters, all in her drive to reach the top and stay there.

With America at war in two theaters of operations, Maggie Higgins ached to get overseas as a correspondent. Seeing her wish granted didn’t seem likely; there were plenty of experienced, hardened men at the Herald Tribune who were readily credentialed by the War Department to work in combat zones, including another Californian named John Steinbeck (who went on to become a leading novelist and Pulitzer Prize winner, as Maggie would).

In late 1944, Maggie Higgins got to Europe and soon found her way to the Herald Tribune’s Paris bureau where her skilled French gave her an edge in reporting. Over the fall and winter that year, as the Allies made their final push into Germany and Austria, she traveled with the US Third Army commanded by General George Patton. She got to know lots of military men—from troops on the ground to top brass—and she made enemies. Some of the other women correspondents, some 20 or more years older than Maggie (who was 24), resented her untidiness. She showed no regard for the older women’s standing or experience. She ignored the smudges of carbon paper on her face and wore her uniform with tennis shoes. Worst were the rumors that Maggie Higgins would sleep with a military man or another reporter in exchange for information.

Whatever others may have thought, Maggie earned her editors’ respect and was rewarded for her reporting when the Herald Tribune named her its Berlin bureau chief in 1947. She covered the transformation of Poland from a republic to a Communist society after the Iron Curtain dropped on Europe, and she watched the Berlin Airlift take off in 1948.

Tongues continued to wag about Marguerite Higgins in Berlin, where she fell in love with a married man, General William Hall. More gossip followed; there was a new book out at home with the provocative title, Shriek with Pleasure, written by Toni Howard, another woman reporter who knew Maggie in Berlin. Its protagonist very much resembled Maggie Higgins, and the plot was a “bitchy little story,” according to Keyes Beech of the Chicago Daily News, who worked with Maggie later. When she was transferred to Tokyo as bureau chief in 1950, it looked like a big step back for Maggie, and some in her circle quietly cheered.

Maggie arrived in April to find Tokyo life quiet and boring—until there was a surprise attack in a neighboring country. On Sunday, June 25, 1950, the North Korean People’s Army, backed by Communist China, crossed over the 38th parallel in a full-court offensive against South Korea. That afternoon, Maggie Higgins showed up at the Haneda airfield to fly to Korea. Three other newsmen were there: Beech of the Chicago Daily News, Burton Crane of the New York Times, and Frank Gibney of Time. Gibney suggested that “Korea was no place for a woman,” but Maggie ignored him. After several false starts and a side trip to southern Japan, they found room on an empty C-54 cargo plane that was to return filled with Americans evacuating Seoul. The pilot was amazed that the four didn’t plan to come back with him.

From Kimpo (now Gimpo) Airfield, where grounded planes were on fire, the four reporters hurried on to Seoul where American military advisors worked and lived. Clearly, South Korea was in chaos, as streams of refugees poured into Seoul from the north, just 35 miles away. Maggie recalled the scene thusly:

The road to Seoul was crowded with refugees. There were hundreds of Korean women with babies bound papoose-style to their backs and huge bundles on their heads. There were scores of trucks, elaborately camouflaged with branches….

It was a moving and rather terrifying experience, there on that rainy road to Seoul, to have the crowds cheer and wave as our little caravan of Americans went by…. I thought then, as I was to think often in later days, I hope we don’t let them down.

The South Koreans fought well but were no match for the Russian-made tanks that ground their way along the Uijeongbu corridor toward Seoul. Late in the night, Maggie—relegated to separate sleeping quarters at American headquarters and separated from the other reporters—was called to evacuate along with American soldiers and move south toward a bridge that crossed the Han River. She watched as the bridge exploded into orange flames. It had been destroyed by the disorganized South Koreans in a defensive move to keep the Communists from moving closer. But the South Koreans had miscalculated their timing, leaving thousands of their own soldiers and citizens— and the Americans—trapped on the north bank of the Han. There seemed to be no other way across the river.

In the midst of retreat, an American colonel pointed out to Maggie that she could file a story from a nearby radio truck. She grabbed her typewriter,

put it on the front of the jeep, and typed furiously. Streams of retreating South Korean soldiers were then passing our stationary convoy. Many of them turned their heads and gaped at the sight of an American woman, dressed in a navy-blue skirt, flowered blouse, and bright blue sweater, typing away on a jeep in the haze of daybreak. I got my copy all right. But as far as I know, communications never were established long enough to send it.

The Americans commandeered tiny boats and began to push across the river, pointing rifles at anyone who threatened them. It was havoc all around as people tried to escape. Korean soldiers shot at fleeing boatmen, hoping they would return to shore so they could escape as well. Others stormed the smaller craft and swamped them as they climbed in. Maggie was separated from the other reporters, and she crossed the Han River safely. A single file of refugees then marched up a mountain trail toward Suwon, South Korea’s brand new temporary capital. The group included the Korean minister of the interior, South Korean soldiers, an old man, diplomats, children, and Maggie Higgins.

In the opening assaults of the Korean War, Maggie and the other reporters witnessed—and lived through—four evacuations in 10 days. Maggie saw the very first American death in that war, as 19-year-old Private Kenneth Shadrick lifted his head to take aim and was shot. The reporters could only shake their heads, knowing that these young soldiers had just finished basic training and had no real battle experience. Outnumbered and green, these young men and their commanders had sacrificed themselves. “Are you correspondents telling the people back home the truth?” a 26-year-old lieutenant barked at Maggie. “Are you telling them that out of one platoon of 20 men, we have three left? Are you telling them that we have nothing to fight with, and that it is an utterly useless war?” Maggie did, in a book she titled simply, War in Korea: The Report of a Woman Combat Correspondent.

If Maggie had held communist sympathies during college, she abandoned them when she reported on the Korean War:

We know now that it is fortunate for our world that it resisted Red aggression at that time and in that place. Korea has served as a kind of international alarm clock to wake up the world.

There is a dangerous gap between the mobilized might of the free world and the armaments of the Red world—the Red world which, since 1945, has been talking peace and rushing preparations for war. Korea ripped away our complacency, our smug feeling that all we had to do for our safety was to build bigger atomic bombs. Korea has shown how weak America was. It has shown how desperately we needed to arm and to produce tough, hard-fighting foot soldiers. It was better to find this out in Korea and in June of 1950 than on our own shores and possibly too late.

In the midst of trying to dodge gunfire, evacuate, write stories, and file them on time—yet another challenge—Maggie had problems of her own. Homer Bigart arrived in Korea and pulled rank on Maggie, ordering her to go back to Tokyo. Maggie protested: there was plenty of work for them both. But then Bigart got nasty and threatened to get her fired.

Bigart also told Maggie that she didn’t have a single friend in Tokyo, which both puzzled and bothered her. She wondered what was going on. She learned later that four other news bureau chiefs in Seoul, the so-called “Palace Guard,” who alone had access to General Douglas MacArthur, were furious when she broke the story about American bombings north of the 38th parallel. The four had agreed to release the news together at a later date and now believed that Maggie had gotten the privileged information from MacArthur himself. Maggie insisted she knew nothing of the agreement but she did know about the bombings—from a completely different source.

As Homer Bigart continued to harass Maggie, she sent a message to the bosses in New York asking permission to stay on. Days later, when she still had no answer back, she worried about what to do. She sought out her friend Carl Mydans, the Time and Life magazine photographer, to share her worries. Mydans asked her a piercing question: “What is more important to you, Maggie, the experience of covering the Korean War or fears of losing your job?”

Maggie Higgins stayed on in Korea. In mid-July, as she covered the Battle of Taejon in a jeep scrounged by Keyes Beech, Maggie got a rude shock of her own. The army was expelling her from Korea. She wrote that the news felt as though she’d been hit by gunfire. She was ordered out of the Korean theater of war immediately, and no one could explain why.

Tensions between army brass and war correspondents had arisen in Korea. It looked as though MacArthur’s headquarters thought the press was more hindrance than help to their war effort. Maggie thought that MacArthur’s press chief viewed the press corps as natural enemies. Correspondents were allowed use of the telephone only in the dead of night. It didn’t matter if the line was free of other military traffic during waking hours. The only sure way a reporter could file her stories was to have them flown to Tokyo.

I had already been with the troops three weeks. Now, with an entire division in the line and more due to arrive, the worst had already been endured. Realizing that as a female I was an obvious target for comment, I had taken great pains not to ask for anything that could possibly be construed as a special favor. Like the rest of the correspondents, when not sleeping on the ground at the front with an individual unit, I usually occupied a table top in the big, sprawling room at Taejon from which we telephoned. The custom was to come back from the front, bang out your story, and stretch out on the table top. You would try to sleep, despite the noise of other stories being shouted into the phone, till your turn came to read your story to Tokyo. Then, no matter what the hour, you would probably start out again because the front lines were changing so fast you could not risk staying away any longer than necessary.

General Walton H. Walker had ousted Maggie because she was a female and “there are no facilities for ladies at the front.” Maggie retorted that there was no lack of bushes in Korea. She appealed Walker’s declaration all the way to MacArthur at headquarters and stayed on the job until she was forced to take a train from the battle zone to army headquarters. When she arrived, hoping to make a personal plea to Walker, she was greeted by an army captain who put her in a jeep. The captain, armed with a carbine and a pair of armed soldiers, escorted Maggie directly to the airstrip. As they sped along, the captain “further clarified his views on women correspondents.”

By the time Maggie landed in Tokyo, MacArthur had rescinded the order to expel her from Korea. None other than Helen Rogers Reid, president of the New York Herald Tribune had cabled MacArthur—whose word was law in that part of the world—asking him to permit Maggie to go back to work. MacArthur’s orders read: “Ban on women in Korea being lifted. Marguerite Higgins held in highest professional esteem by everyone.”

Back to work Maggie went. She was eating breakfast at US Army headquarters at Chingdoi, situated in an old wooden schoolhouse, when bullets and grenades blew through the walls.

I started to say something to Martin [Harold Martin of the Saturday Evening Post] as he crouched by the telephone methodically recording the battle in his notebook. My teeth were chattering uncontrollably, I discovered, and in shame I broke off after the first disgraceful squeak of words.

Certain that her life was ending, Maggie felt surprised that death was going to happen to her.

Then, as the conviction grew, I became hard inside and comparatively calm. I ceased worrying. Physically the result was that my teeth stopped chattering and my hands ceased shaking. This was a relief, as I would have been acutely embarrassed had any one caught me in that state.

Fortunately, by the time [Colonel John] Michaelis came around the corner and said, “How you doin’, kid?” I was able to answer in a respectably self-contained tone of voice, “Just fine, sir.”

When the fighting grew desperate and casualties overwhelmed army medics, Maggie picked up glass bottles of blood plasma to administer to wounded soldiers. The grateful commander wrote a letter to the Herald Tribune extolling Maggie’s bravery under fire. From then on, Maggie carried a carbine (rifle) when she rode shotgun in Keyes Beech’s jeep. It would not have done any damage against a Soviet tank, but the carbine represented some kind of defense against North Korean soldiers.

By early August 1950, the North Koreans had pushed so far south that UN forces were squeezed into a small area of southeast South Korea. All the Americans could do was defend themselves until more soldiers, supplies, and aircraft could arrive to rejuvenate them. On September 15, MacArthur struck back at North Korea by staging an amphibious assault on the peninsula’s west coast at Inchon, 30 miles from Seoul.

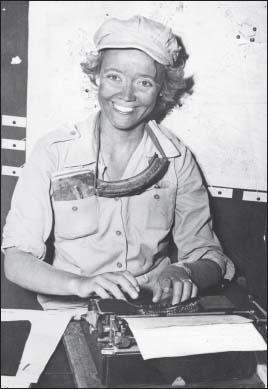

Marguerite Higgins typing in an army office in Korea, her face dirty from working in the field. Marguerite Higgins Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Library

Maggie needed to get to the scene by ship, but the US Navy forbade access because she was a woman. Just as fast, her luck changed when there was a mix-up in paperwork. Maggie found herself allowed to board the USS Henrico, the command ship of a group of transports. She was at sea four days until it was time to drop into a landing craft and go ashore. Her memoir left a blunt, picturesque review of how a fighting man carried out an assault from the sea:

At three o’clock orders went out to lower the rectangular, flat-bottomed craft into the sea, and the squeaks of turning winches filled the air. From the deck I watched the same operation on the other transports, strung out down the channel as far as the eye could travel.

I was to go in the fifth wave to hit Red Beach. In our craft would be a mortar outfit, some riflemen, a photographer, John Davies of the Newark Daily News, and Lionel Crane of the London Daily Express.

There was a final briefing emphasizing the split-second timing that was so vital. The tide would be at the right height for only four hours. We would strike at 5:30, half an hour before dead high. Assault waves, consisting of six landing craft lined up abreast, would hit the beach at two-minute intervals. This part of the operation had to be completed within an hour in order to permit the approach of larger landing ship tanks (LSTs), which would supply us with all our heavy equipment. The LSTs would hit the beach at high tide and then, as the waters ebbed away, be stranded helplessly on the mud flats. After eight o’clock, sea approaches to the assaulting marines would be cut off until the next high tide. It was a risk that had to be taken.

Maggie worked her way down the ship’s side, hanging onto a net as she felt with her feet for the swaying rungs underneath. She “dropped last into the boat, which was now packed with 38 heavily laden marines, ponchos on their backs and rifles on their shoulders” as they waited for the rest of the landing craft in wave number five. Some of the marines were playing cards.

Finally we pulled out of the circle and started toward the assault control ship, nine miles down the channel….

Red Beach stretched out flatly directly behind the sea wall. Then after several hundred yards it rose sharply to form a cliff on the left side of the beach. Behind the cliff was a cemetery, one of our principal objectives.

At the control ship we circled again, waiting for H hour.

Aircraft carriers and navy cruisers bombarded the beach in a final pounding. There was silence, until an air assault swept over the landing craft. Silence again followed, and then another assault. Then more silence.

The control ship signaled that it was our turn. “Here we go keep your heads down!” shouted Lieutenant [R. J.] Shening. As we rushed toward the sea wall an amber-colored star shell burst above the beach. It meant that our first objective, the cemetery, had been taken. But before we could even begin to relax, brightly colored tracer bullets cut across our bow and across the open top of our boat. I heard the authoritative rattle of machine guns. Somehow the enemy had survived the terrible pounding they’d been getting. No matter what had happened to the first four waves, the Reds had sighted us and their aim was excellent. We all hunched deep into the boat.

“Look at their faces now,” John Davies whispered to me. The faces of the men in our boat, including the gin-rummy players, were contorted with fear.

Their boat smashed into the sea wall as bullets whined overhead. The marines still crouched in the boat.

“Come on, you big, brave marines let’s get the hell out of here,” yelled Lieutenant Shening, emphasizing his words with good, hard shoves.

The first marines were now clambering out of the bow of the boat. The photographer announced that he had had enough and was going straight back to the transport with the boat. For a second I was tempted to go with him. Then a new burst of fire made me decide to get out of the boat fast. I maneuvered my typewriter into a position where I could reach it once I had dropped over the side. I got a footing on the steel ledge on the side of the boat and pushed myself over. I landed in about three feet of water in the dip of the sea wall.

A warning burst, probably a grenade, forced us all down, and we snaked along on our stomachs over the boulders to a sort of curve below the top of the dip. It gave us a cover of sorts from the tracer bullets, and we three newsmen and most of the marines flattened out and waited there….

One marine ventured over the ridge, but he jumped back so hurriedly that he stamped one foot hard onto my bottom. This fortunately has considerable padding, but it did hurt, and I’m afraid I said somewhat snappishly, “Hey, it isn’t as frantic as all that.” He removed his foot hastily and apologized in a tone that indicated his amazement that he had been walking on a woman….

Suddenly there was a great surge of water. A huge LST was bearing down on us, its plank door halfway down. A few more feet and we would be smashed. Everyone started shouting and, tracer bullets or not we got out of there.”

Maggie’s typewriter survived the assault, but she never explained how she kept her paper dry.

Maggie made it to the navy’s flagship USS Mount McKinley, the only place any reporter could file a story about the invasion of Inchon. Then she was discovered and forbidden to return to the McKinley between 9 PM and 9 AM, a distinct disadvantage because New York Times reporters could file a story when she couldn’t. She slept on shore, greatly annoyed that the male reporters who bunked on the McKinley had real eggs, not the disgusting powdered kind, for breakfast.

After the Korean War, Marguerite Higgins married General Bill Hall in 1952. They had three children. Their first arrived premature and lived only five days. Maggie’s heart was broken. She had seen death so many times, and she had thought about soldiers’ families who would grieve when an army chaplain knocked on their doors. Following her daughter’s death, she was grateful for “the warmth and new life infused in me by the compassion of others,” she wrote in News is a Singular Thing, her memoir published in 1955. It was the first time that Maggie admitted that she understood what real compassion was.

Just in her mid-30s when she sat down to reflect on the 11 years she’d worked as a war correspondent, Maggie’s words spoke with a growing maturity and self-awareness about the story of her own life.

For the simplest facts—the difficulty of love, the futility of resentment, man’s degradation under tyranny—do not really come through to me until I find them out myself from personal experience … until I made these journeys they meant nothing, for I did not understand how they applied to me and to my times.

It was unusual in the 1950s for a married woman with children to work outside her home. Maggie Higgins did—and she kept her own name on her byline. She traveled back and forth to war zones through the rest of that decade and went to Vietnam 10 times, starting in 1963. That year she won prestige by becoming a columnist for Newsday.

Sometime during her travels to Southeast Asia, she was bitten by a sand flea that infected her with a fatal illness. Doctors couldn’t determine what she had for weeks until they diagnosed leishmaniasis, a flesh-eating tropical disease, but they had no effective way to treat her. (Leishmaniasis is treated today with a round of antibiotics costing less than $10.) As she grew more ill, she was moved to Walter Reed Army Hospital, where Maggie continued to work in her hospital bed.

On January 3, 1966, she died at Walter Reed; she was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. Marguerite Higgins Hall was 45 and left two young children and her husband.

In the later part of the 1900s, Marguerite Higgins became the subject of both popular biographies and scholarly research in women’s history that raised questions. Was Marguerite Higgins the cold, scheming, take-no-prisoners woman portrayed by some of her biographers? Or was Higgins condemned because she was a woman who behaved like a man in going after what she wanted?

In his memoir, Tokyo and Points East, Keyes Beech devoted a chapter to Maggie Higgins. Beech, who liked and respected women, drew an evenhanded assessment of his coworker. Yet in the same passage, Beech’s words reflected a view of women common to men of his generation:

Despite her success, Higgins never gave her readers what they really wanted. What they wanted was the “woman’s angle” on war. To her credit, Higgins never stooped to that. Any one of her dispatches might have been written by a man.

In her quest for fame, Higgins was appallingly single-minded. Almost frightening in her determination to overcome all obstacles. But so far as her trade was concerned, she had more guts, more staying power, and more resourcefulness than 90 percent of her detractors. She was a good newspaperman.

It was a tragedy for the world to lose Marguerite Higgins at such a young age. No doubt there was much more for her to say.