21

What We Make

My parents were madly in love during my childhood and liked being away from us. Who could blame them? We were kids! “Children are to be seen and not heard!” they’d say with humor and reprimand. They punished us but they didn’t beat the shit out of us and I’m very grateful for that. When they took a break from us to go on vacation, they’d say, “We’re getting away from you guys!” We’d stay at Nonnie and Glenn’s, and sometimes my uncle Mark would give us a ride back to Monroe. A few times, I was put on a Greyhound bus, which was cool.

Mark was my father’s younger brother and came into the world on a visit from Paw Paw to Granny, who had to have been at the height of her longing for him. Paw Paw delivered just on time—you could say he made his mark.

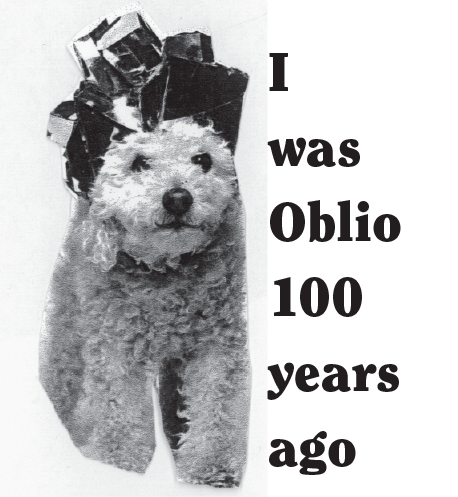

We’d roll down the windows and turn up the radio on those drives in his brown lowrider; “My Sharona” became “Rice-A-Roni” and that was the funniest thing we’d ever heard. I’d take Oblio, our miniature black poodle, and we’d both stick our heads out the window to catch the breeze. I loved Oblio. He was named after a character in my favorite album, The Point! by Harry Nilsson, about a little boy who had a round head in a town where everyone else had pointed heads. It had a point about pointlessness, which is a good point.

One trip, Uncle Mark had his friends in the car when he picked us up, and I was smushed next to a lady in the backseat who was smoking a tiny cigarette with something that looked like a bobby pin, that was pretty when she put it in her hair. We were going to some backwoods place where they taught us how to shoot BB guns and we shot cans off a fence post. I stepped on the cans, crunching them down in the middle of my sneakers to make tap shoes, and danced around while the grown-ups were doing their own thing. That was a fun day.

Uncle Mark, in those days, resembled Tom Waits so much that I’d look at his albums, like Small Change and Closing Time, and ask him if it was him on the album cover. I was six. Albums were a big thing at our house and in our family. I remember showing my dad’s records to a stranger at the front door once. The door was windowpaned, and I could only hold, like, ten at a time, so I flipped them with my little hands. The man was laughing, because I wouldn’t let him in. Even though I could tell he was to be trusted, I couldn’t let strangers in the house when I was alone. Oh, the benign neglect of the seventies, I’m blessed to have been born at that time.

It was around the time the song “Wildfire” was on the radio. The song was about a woman who’d lost her horse in a fire and our narrator, the singer Michael Martin Murphey, is haunted by her ghost. She ran away, calling out “Wildfire,” and that’s basically the song. Those story songs of the seventies could be sentimental and intense but I loved all that. “Get these hard times right on out of our minds / Riding Wildfire . . .”

Uncle Mark would come over for dinner and afterward we all sat on the couch and watched TV or listened to albums. My mom would do what she called her “surgery,” and take the shade off the lamp. She’d beg and demand him, “Come here, come here, come HERE!” and he’d go to her, like a dirty kid who’s been playing outside and the sun’s gone down and he’s not ready for a bath.

She was ready for him to lie on her lap when she had her accoutrements (needle and rubbing alcohol) ready and then she did the surgery, which was popping the bumps on his face. I’d hear screams from both of them. “That was the BEST!” Laughing and screaming with giddy disgust. “GROSS! AHHHHH!!!!” and “I don’t think that one’s ready, but this one is,” and, “Oh! That was a good one!” She hurt him so bad that I remember him leaping off the couch. The naked lampshade, with the bulb exposed, and Uncle Mark, holding his face—and kind of laughing? It was good times. Sometimes I perched on the back of the couch, like a gargoyle, and got my mom anything she asked for.

One afternoon, on a ride back from Shreveport, my mom broke the news about Oblio. She told us that Uncle Mark had left the fence unlocked and Oblio had run across the street and gotten hit by a car. We were all bawling in the front seat and there was nothing in the car to blow our noses with. Then my mom said, “I have some clean underwear in my bag in the back.” I flipped over to the backseat and found a clean pair. “It’s really okay to use your underwear, Mom?” She said that it was and started giggling through her tears. I hopped over the front to share, where we laughed as hard as we cried.

Not long after, I was wandering around the house and ended up by my mom’s old sewing machine side table. I liked to sit on the two-by-two-inch pedal and rock back and forth, like I was on a sideways seesaw; I’d hold on to the outside edges of the top and go as fast as I could, rocking myself dizzy until I had to slow down.

Behind the sewing machine, a little miracle appeared. My mom, who revered a clean house and found her sense of peace in the vacuum, had overlooked something: a petrified piece of Oblio’s poo-poo. It was dried and hard and mostly white and green, and it was absolutely precious to me. I considered it to be from Oblio in heaven. I took it and went upstairs to wrap it in one of Granny’s handkerchiefs, which I kept in the top drawer of my chifforobe. I kept it and revisited it, like a cherished relic, with all the love in my heart.

The very first thing each of us makes in life is our poop and we don’t even have to think to do it because it just happens. What a gift to the mind of a child. This, of course, wears off, and it’s too bad that it smells. One of the first times I got in “big trouble” was when my brother and I were three years old and a smell was coming from our room. The smell was so strong that it woke up my parents. My dad came in and saw us with our shit in our hands and in the crevices of our crib and on our faces: we were happy and proud of what we’d made. My dad didn’t see it that way and he swung us up by our elbows and spanked us.

That was the first time I experienced art producing punishment or shame. Oh shit, that’s funny.