A lthough we don’t really know how the brain generates the mind, we do have a pretty good understanding of what different regions of the brain do and how they are connected to one another by various pathways.

Popular science will tell you that the major distinction inside your head is “right brain” versus “left brain.” Please delete that thought from your memory banks. You will hear people say, “I am a right-brained person.” Rubbish. Although the right and left sides of the brain have some differences, they actually have far more things in common. More important, the two sides of the brain are always working together. It’s not like the right brain and left brain work independently. You only have one brain at work.

The way you really need to think about the brain’s anatomy is in a hierarchical way: superficial brain (cortex) versus deep brain (subcortex). You are about to read a very gross oversimplification of the brain’s architecture, but for your purposes (as a trader or investor), it’s all you really need to know.

Some people like to think that trading is all about logic: analyzing all available data, considering the various pros and cons of different courses of action, and then coming to a logically sound conclusion. If only it were that simple!!

Sure, intellectually smarter people do, by and large, make for better traders. Sound logical reasoning is a valued asset for any trader. And the more practical wisdom you have gathered from real-world experiences over the years also helps. But clearly intelligence is not the whole picture.

In fact, there are plenty of very successful traders who sport very normal intelligence quotients (IQs). There have also been bloody geniuses who failed miserably trying to trade the markets. Take, for example, Sir Isaac Newton, the man who single-handedly solved the riddle of gravity and then went on to figure out the laws of motion for the entire universe. Were you aware that Newton (despite knowing so much about gravity, falls, and crashes) was wiped out by the 1720 stock market crash because his emotions got the best of him in a bubble market? Emotionally charged with excitement by a peaking market, Newton purchased stocks at precisely the wrong time.

Poor Newton. He fell for the same old temptation that to this day still propels many bright, but novice, investors and traders into ruin: enthusiastically buying at market peaks and selling in a panic, when it is too late and the market has already hit a new low. It’s an emotional pattern as old and true as time itself. Logically, we all know to buy low and sell high. Emotionally, we often do the reverse.

Here is a great quote from Buck Rogers (the IBM Buck Rogers, not the science fiction one): “People buy emotionally, then justify with logic.”

This quote gets to the fact that people all too frequently make purchasing (or investing) decisions based purely on emotions, with little logic behind them. They may well rationalize their decision afterwards by using logic, but the decision itself is often made on emotion, with logic only playing a secondary role.

Ask yourself this: The last time you bought a new gadget, let’s say a mobile phone, did you choose the make and model based on an absolutely complete review and comparison of all the handsets available on the market? Did you really read, analyze, and do a side-by-side comparison of all the detailed specs, features, and prices of the phones there were to choose from?

Or did you only briefly look at the main specs and then buy the phone because it “looked cool” (a sleek design, a catchy marketing campaign, or perhaps it’s the make that is all the rage right now)? Did you actually buy the phone based more on a “feeling” that it was the right one? Did you even buy it simply because you desired it?

They don’t call it “buyer’s remorse” for nothing! You make a purchase based on your feelings, but it’s only after you get home and unpack your new phone that you realize there are a few shortcomings to it . . . things that you did not know about, or even contemplate, prior to the purchase. Maybe the speaker phone is not quite loud enough, and it turns out that it’s the most important feature for your telephoning needs. Or maybe several days later you learn about a new phone model that is about to be released that is even more appealing and “cool” than the one you just bought. If only you had investigated a little more! And of course the store knows all about buyer’s remorse. That’s why it has a 15 percent restocking fee!

Oftentimes we don’t realize that this process is happening in the moment, because rarely do we think long and hard about how deeply our emotions are influencing us. We just feel them.

Why does this happen? It’s actually simple anatomy.

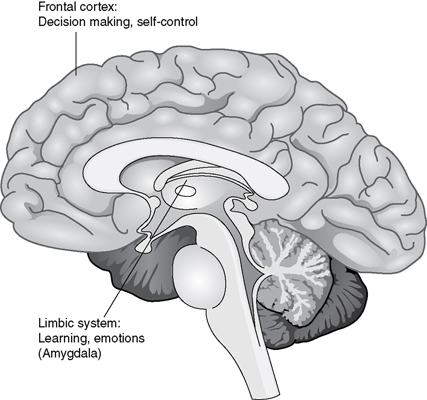

Like I said, our brains have two main parts: an outer shell and an inner core. The brain’s shell is the cerebral cortex and is the outermost layer of the brain. The cortex near the front of the brain is the part we use purposefully, while other cortical areas are hard at work without our even being aware of them (receiving, interpreting, and processing information). The core, on the other hand, is located underneath the shell; it is composed of the limbic system and amygdala and is often referred to as the subcortex.

The core of the brain is where emotions and memories are formed and kept, while the shell is where complex thoughts, decisions, and behaviors are orchestrated and initiated. See Figure 3.1.

The core is tucked away in the center of the brain and is primeval. It is where most of the basic and primitive mental functions reside—our sense of survival, fear, anger, hunger, sex drive, and so on. The core is primarily designed to makes decisions very quickly and in a very black and white manner. The core does not “think.” It reacts!

What happens if you are walking along in the jungle and suddenly you see a tiger step out from the brush? You flee as fast as you can, naturally. This decision to immediately flee is all related to your brain’s anatomy. Again, your memory (the last time I came across a tiger, it killed and ate my brother) and your feelings (I miss my brother) are located in your core, and it is your core that allows you to flee such a dangerous or hostile situation without giving it a second thought.

Figure 3.1 Basic brain anatomy: the core versus the shell.

In evolutionary terms the cortex, or shell, is a much more recent development. The shell of our brains is also what separates us humans from other animals, including other primates. The shell is what gives humans intelligence and the spark of creativity. The cortex, especially in the frontal areas, is “the CEO of the brain”: it plans, interprets, organizes, draws conclusions based on prior experiences, forms theories and hypotheses, weighs pros and cons, and makes decisions.

Another primary purpose of the shell is to regulate and modulate what the core is doing. For example, if the core tells us to be afraid because we hear a loud bang, the shell will analyze the situation and decide whether the bang is truly a danger that we should run away from, or if, instead, it is from a totally harmless source and can be filtered out and ignored, or even if the bang is actually a call of distress from somebody we love and who needs our urgent help, meaning we should actually be rushing toward the bang, not away from it!

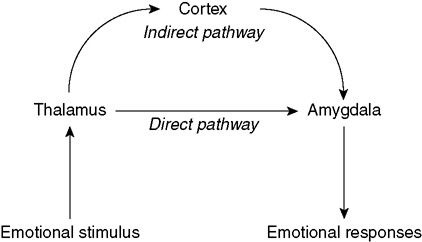

There are two main brain pathways, or circuits, that transmit and handle various stimuli. In everyday life humans often use the indirect pathway to make important decisions. That is, emotional stimuli are routed through the core (especially via an area called the thalamus), to the shell/cortex (which analyses them). The cortex then sends appropriate responses to a core area called the amygdala. These pathways are illustrated in Figure 3.2.

This indirect pathway is slow, but it is precise, in that the data can be carefully scrutinized before being acted upon. Humans have this unique ability in that they can use the cortex to sort out various complicated emotions and perceptions and make good decisions in carrying out their responses (behaviors).

However, a lot of times this flow of emotional data gets “short circuited” through the direct pathway, entirely bypassing the cortex. Emotional stimuli automatically trigger responses with the cortex being totally left out. The result is a very fast response, based largely on emotions and without much thought or logic going on. While lightning fast, the downside of this direct pathway is that it offers only a very crude analysis of the incoming data.

Figure 3.2 The two pathways for managing emotional stimuli.

For example, imagine you are a lost hiker trying to find your way out of the wilderness. You are out of water and are slowly becoming dehydrated under the blazing hot sun. As you continue on your way looking for rescue, out of the corner of your eye you see a large snake. Immediately you are frightened. You stop and prepare to flee. After all, the last thing you need right now is a bite from a poisonous snake.

But then, as you look closer, you realize that is no snake at all. It turns out to be a root that has somewhat the shape, size, and color of a snake! No longer frightened, you continue on your way—until you remember that roots have moisture in them. Moisture you desperately need. You run back over to the root, pick it up, and start chewing on it. What you first perceived as a danger turned out to be a godsend.

Your first reaction to the stimulus, to stop and prepare to flee, used the very crude, but very fast, direct pathway in the brain, the one where the cortex is left out. But eventually your cortex caught up: you employed the indirect pathway in your brain, and hence you were able process more detailed information and make a better judgment call.

Of course, if it had been a large poisonous snake, you would have been very grateful for the crude and fast direct pathway. So it really is nice to have a healthy balance of both of these systems working at all times.

That is, it takes both the logical brain and the emotional brain (along with healthy doses of wisdom, experience, and just plain luck) to be successful at finding your way out of a wilderness . . . and into successful market trading!

But there are times when the cortex gets left out, or at most does not get involved until after a decision has already been made and executed through the rapid pathway. In the case of the lost hiker, for example, he could very well have dashed away in the opposite direction before his cortex realized that it was a root and not a snake. In a case such as this, the fast and crude short-circuiting of information through the primeval region of the brain can be harmful. This improper or untimely short-circuiting through the direct pathway happens to even the best and wisest of brains. In fact, some people have programmed their brains to act in this manner on a regular basis.

The good news and most important message of this chapter is this: the shell part of your brain can be trained to better sense, interpret, and use raw emotions, as well as to modulate its own responses to them. This type of training is called cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and we will have an entire chapter discussing it, including the newest and hottest form of cognitive therapy, called CBM: cognitive bias modification.

Some people may need to learn how to temper or limit their emotional reactions, while others may need to learn how to tap into them better. That is, some individuals have probably trained their brains to depend too heavily on the indirect pathway, always looking for a logical answer.

Take for example Star Trek’s Mr. Spock. Totally devoid of emotion and relying purely on logic, he would probably never have survived in the real world (let alone market trading). While calmly analyzing the percentage chances of being eaten by that saber-toothed tiger about to attack him, he’d already have been devoured for lunch!

Most of us are not like Mr. Spock. For most of us the ingrained power of the older and deeper parts of the brain (our emotions) often and easily overpowers the logical, analytical, and newer parts of the brain. And it is for this reason that traders find themselves doing things that make no logical sense in retrospect but that make perfect emotional sense at the time.

This pattern (emotions getting in the way of sound logical thinking) is just part of being human and how we developed as a species. The point is not to get rid of our emotions entirely but to appreciate and understand them, manage them better, and tap into them when that is called for. We don’t want our feelings to dominate or control our God-given human intelligence and ability to think logically, but we equally don’t want our emotions to be totally squashed or ignored by our intellect. Pure rationality with no appreciation of emotions can be just as deadly for your trading as sheer emotion, unbridled and unchecked by sound reasoning. Remember, when there really is a poisonous snake or tiger crossing your pathway, you do want your anxiety to take over you and cause you to jump back!

George Soros, regardless if you agree with his political beliefs or not, certainly has been one of the better hedge-fund managers and traders of modern times. In his 1995 book, Soros on Soros: Staying Ahead of the Curve, he describes how he would make trading decisions based on when he would get a backache.

I rely a great deal on animal instincts. When I was actively running the fund, I suffered from backache. I used the onset of acute pain as a signal that there was something wrong in my portfolio. The backache didn’t tell me what was wrong—you know, lower back for short positions, left shoulder for currencies—but it did prompt me to look for something amiss when I might not have done so otherwise.1

Soros is not nuts when he says this. What he may or may not have clearly understood is that his back is directly connected to his brain by nerves and that emotional stress or dysregulation in his brain can indeed cause somatic or bodily sensations, such as pain, GI symptoms, and so forth. In fact, there is a whole field of medicine devoted to the study of the two-way highway between the brain and the body: psychosomatic medicine.

Anyway, the point is that emotions (a.k.a. “gut feelings,” sensations, and so on) are very important and should not be ignored altogether. Figuring out how to appreciate, decipher, manage, and use your raw emotions to your advantage is very, very important to successful trading.

Just how important are gut feelings? The nerve that connects your gut to your brain is called the vagus nerve, a.k.a. the tenth cranial nerve. It turns out that about 80–90 percent of the fibers in the vagus nerve are afferent (relaying data toward the brain) and only 10 percent are efferent (sending data away from the brain). More simply put, the vast majority of the traffic on the highway that runs between the gut (as well as other organs) and the brain is, in fact, going toward the brain, and only a small portion is travelling away from the brain. So, quite literally, your gut is feeding neuronal information to your brain all the time and in huge quantities. Your gut loves to talk to your brain. To an extent, it probably pays to listen to your gut when trading!

Of course too much of a good things is never good. Although they have a very legitimate role in every investor’s arsenal, intuition and gut feelings perceived and mediated by the deeper aspects of your brain should always play a subordinate role to, and should never dominate, the CEO of your brain (that is, the cortex).

Canadian journalist and author Malcolm Gladwell has sold millions of copies of his book Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (2005)2, in which he proposes that quick and spontaneous (impulsive) decisions can be just as good as carefully planned, deliberate and analytically derived decisions. While he is certainly a very popular pseudoscientist, Gladwell is by no means an academic or a researcher. His theories clearly start to break down and prove themselves flawed if applied to trading the markets or other forms of complex, high-stakes, fast-paced emotional-rollercoaster activities.

In a rebuttal to Gladwell’s book, journalist Michael LeGault wrote Think: Why Crucial Decisions Can’t Be Made in the Blink of an Eye (2006).3 Unlike Gladwell, LeGault argues in Think that America (and indeed the entire Western culture) is in decline because of a current intellectual crisis. LeGault asserts that snap and spontaneous decisions are detrimental to our society; he maintains that relying on emotion and gut instinct, instead of critical reasoning and facts, is ultimately a threat to our freedom and way of life.

The truth, of course, is that humans have to adeptly use and combine both their intuitive and their analytical powers if they want to succeed at anything, including market investments. You, as a trader, need to draw on both anatomical areas of your brain: the shell and the core. You need to feel and you need to think. The challenge is to strike the right balance between thinking and feeling at any given moment.

The human brain . . . what a mighty machine. Although it only comprises about 2 percent of your total body weight, your brain actually consumes 20 percent of the oxygen you breathe in and 20 percent of the total calories you burn. There is a myth that you only use 10 percent of your brain. You actually use your whole brain all the time—it’s just that you are not aware of most of your brain’s activity and function. It’s not like 90 percent of your brain is lying dormant and wasting away, waiting for you to find a magic switch to turn it on. That’s a pipe dream: that somehow, if you could tap into and harness the dormant 90 percent of your brain, you would be 10 times as productive, smart, clever, or what have you.

What this 90 percent number really means is that the vast majority of what is going on around you at any given moment is filtered out and totally ignored by the 10 percent of your brain that is aware of things. Your body’s mainframe cannot afford to waste time or energy on interpreting meaningless information and background noise. Your brain would go into information overload if it had to devote equal attention and energy to every single stimulus that it could possibly pick up from your various senses.

The deeper core of the brain does a lot of the unconscious filtering out, deciding what is important for your higher brain to make sense of and act upon. This deeper brain structure sounds an alarm any time it senses something out of the ordinary, and it alerts the cortex to it. By first filtering out the millions upon millions of stimuli that are going on and, for the most part, remaining the same around you, your core can bring to your shell’s attention any changes or anything unexpected in front of you.

There is one more key anatomical area of the brain we need to map out in this chapter in order for the rest of the book to make sense. Buried deep in the brain’s core is a structure called the nucleus accumbens. What is important to know about this structure is that it’s the seat of reward, pleasure, and addictive behaviors. Both basic and more luxurious (motivated) rewards (such as food, drink, sex, shelter, pleasant aromas, music, pretty faces, drugs, and so on) create “feel-good” experiences by activating neurons in the nucleus accumbens. These neurons are programmed to deliver “shots” of the feel-good neurotransmitter dopamine every time they are activated.

The nucleus accumbens is essential for the survival of our species. Turn off pleasure, and you basically turn off the will to live. However, chronic or excessive stimulation of the brain’s pleasure center drives the process of addictive behaviors, and with prolonged stimulation of these neurons, the signal attenuates and gets weaker. Consequently you have to consume/take/do more of the same “drug” to get the same effect—you are building up tolerance. And so you consume more.

You can probably see, then, how the nucleus accumbens figures prominently in the brain of an unregulated investor or a gambler who is enjoying these activities because of the pleasurable sensation they bring. And you can see how this vicious cycle, once activated, can be hard to break.

The key thing for traders to realize about the nucleus accumbens is that money (or, more specifically, the desire or idea of making money) causes the neurons in this reward network to fire like wild. Again, this deep-brain network was created and designed with a clear and useful purpose in mind: survival of the species. And although it runs on and is enhanced by pleasure derived from sex, good food, or being successful at doing something, its neurons can easily be hijacked by excessive behavior and lead to disaster.

Interestingly, research has shown that this reward network in the brain gets especially excited about the anticipation of rewards, even more so than the rewards themselves! It turns out that the thrill of anticipating rewards (looking forward to having good sex, a delicious meal, or making money) is actually more stimulating to the reward system and brings more euphoria than the actual achieving or fulfilling of those things. So our reward system actually rewards us for wanting to capture uncertain rewards and to take risks to do so. Ironically, this means it also causes us to expect that the future will be more wonderful than it actually is, once it arrives. Basically, our brains are tricking us into a reinforcing reward system that never quite meets our expectations.

Think of the heroin addict who, upon seeing an empty syringe at the doctor’s office, begins to feel intense and irresistible cravings to use some dope. Just the mere sight of this visual cue causes the addict to feel a rush of euphoria in his nucleus accumbens and the rest of the reward pathway. The reward pathway in this addict has become a runaway train: The developed behavior of “shooting up” is throwing fuel onto the fire by continuing to reinforce the reward pathway. At some point the heroin addict may not even get much of a “high” any more from using the drug, but the reward system is so hyperactive that he still has a huge urge to use whenever he sees the syringe or has other cues presented to him (social cues, for instance).

As we will see later in this book, this reward network (which we all come prewired with) can become especially problematic for futures traders who are trading for the sole purpose of getting a rush out of trading. Their anticipation and reward circuits get carried away. These traders will start placing trades in response to their own set of cues, when, in fact, they should not be placing a trade at all. And it turns out (as we shall see) that some traders are more likely to take on this maladaptive behavior than others. Their personality profile puts them at greater risk of falling prey to the vicious cycle of throwing fuel onto the positive-feedback system of rewards, and this, in the end, diverts them from making money in the markets.

Naturally there is a lot more to the anatomy of the human brain than what you just read; again, this is a gross oversimplification. But these are the essential points you will need to know as you read the rest of this book and apply it to your market trading.

Mental Edge Tips

- Striking the right balance between logic and emotion is paramount.

- Don’t let your raw and unexamined emotions get in the way of your logical, deductive, analytical thinking, and likewise don’t let your innate Mr. Spock get in the way of your gut feelings and intuitions. There will be times for each!

- Your brain’s reward center is designed to trick you into thinking that pleasures will be more enjoyable than the anticipation of them. This is an extremely strong reinforcing pathway and can become very problematic for some traders.