Introduction to Personality Traits

Personality traits can be defined as dimensions of individual differences in tendencies to show consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings, and actions. Just as people differ along a spectrum in terms of their cognitive capacities (IQ), age, weight, and height, so too do all people vary in their proneness to certain ideas, moods, and drives.

For instance, some people are innately more emotionally stable and calm, while others are more emotionally labile. Some people are more trusting (perhaps even to the extreme of being naive and prone to being exploited by others), while others are not trusting at all (and hence have few close interactions with others). A person can be optimistic versus pessimistic, dependent versus independent, detail-oriented versus carefree, and so on.

In everyday language all of us frequently describe the temperaments of the people we know and interact with using various adjectives. “He’s an agreeable guy,” or, “She is so gregarious.” In fact, a review of the Oxford English Dictionary finds that there are well over 4,400 different adjectives that can be used to describe human personality traits. Although each of these adjectives is an attempt to describe a personality trait, not every adjective is a personality trait in itself. There are three criteria that must be met for something to be a true personality trait:

1. Enduring—it must not change significantly with time.

2. Pervasive—it must show a consistent pattern across many situations and aspects of life.

3. Distinctive—it must be easily described, assessed, and understood.

Sometimes a particular personality trait is so evident in a person that even the most untrained eye can see it. At other times these traits are inherent, but much more latent, attributes that only can be identified under specific circumstances, that is, when a latent personality trait is brought into play by some challenge or provocation.

Again, as with height or intelligence, all the various human temperamental traits plot out neatly in a smooth and graded fashion around a mean average (that is, the traits of a large number of individuals yield a bell-shaped curve).

The summation of one’s personality traits leads to what can best be described as a personality “type.” Even the ancient Greeks noted four major personality dispositions: sanguine, choleric, melancholic, and phlegmatic. The Greeks thought that four different bodily fluids affect human personality traits and behaviors. Sanguine (blood) referred to the pleasure-seeking and sociable personality, the choleric (yellow bile) individual was ambitious and leaderlike, melancholic (black bile) people were seen as introverted and thoughtful, while those with a relaxed and quiet temperament were labeled by the Greeks as phlegmatic (phlegm). The great Greek physician Hippocrates (460–370 BC) incorporated the four basic human temperaments into his medical theories. From the time of Hippocrates until now, these four temperaments, or slight modifications of them, have been part and parcel of many theories of medicine, psychology, and literature.

People who have personality traits that cluster in a certain type to such an extreme that it frequently results in interpersonal difficulties are said to have a personality “disorder” of one form or another. For example, histrionic personality disorder (previously known as hysterical personality disorder) is defined by extreme emotional lability, self-centeredness, attention-seeking behaviors, flamboyancy, sexual inappropriateness, and shallow self-dramatization.

Besides just grouping and naming personality types, it is important to realize that we can also identify a person’s tendencies to react to circumstances in a particular emotional fashion. Of course we cannot predict with 100 percent certainty how someone with a particular temperament will respond to a specific provocation, but we are able to see that groups of people with certain personality traits tend to think, act, and feel in similar patterns. This is critical to understand.

Consider this analogy using human intelligence: It is impossible to precisely predict which specific questions a high-school student with a particular IQ will miss on her SAT exam. However, we can predict that the students with the highest IQs, in general, will outperform all the other students. We also can predict that the smartest kids will, in general, fare better on the tougher problems. We can even make a fairly educated and accurate prediction of a particular student’s overall score based on her known IQ.

But of course there are many other variables besides raw intelligence that will come into play on exam day, such as what she had for breakfast, how well she slept the night before, how much she studied and retained, and how motivated she is to do well on her exam. Taking into account all these other variables, we can predict with a good deal of reliability which students will perform the best on their SAT. But it takes just one of these other factors to throw our best predictions off. If the student test-taker comes down sick on exam day, for instance, all bets that she will perform at her expected level, given her known IQ, are off.

Likewise, we can predict with some degree of certainty how people with certain personality traits and vulnerabilities will respond or react, given a certain challenge or stressful situation, but there are also plenty of other variables that make bullet-proof predictions impossible.

This brings up another very important point. In general, a person’s unique set of personality traits is generally stable across time. The propensity is for personality to endure and not change much as one ages. Once a person’s brain is fully developed and no longer physically growing (on average this occurs at about age 23), his or her personality traits are—for the most part—determined. They are not exactly set in stone, but they are very hard to change. (We will come back to this critical point in a later chapter, with some evidence that points to the fact that personality can be modified a bit; but for now, be aware of this: since we have little means to change our temperament, our only remaining choice is to better understand it, experience how it affects our lives, and then try our best to adapt to it for the better.)

Given that there are well over 4,000 different words in the English language that can be used to describe a person’s personality, this could lead one to wonder, are they all equally important? Is there some way to discern which personality monikers are most scientifically useful in describing people and in predicting how they will act, feel, or think in certain situations?

Hans Eysenck (1916–1997) was a German-British psychologist and the first “big name” in personality testing. He is still considered the grandfather of modern personality analysis. He applied the statistical process known as factor analysis to human personalities to tease out which traits are most relevant and verifiable. Factor analysis is just a fancy word for using mathematics and statistics to see which things (in this case adjectives describing people) tend to clump together. For example, the adjectives “gregarious,” “talkative,” and “sociable” are not very different from each other. We would expect that those people who are gregarious are also talkative and sociable.

In one of his key early experiments, done in 1947, Eysenck studied the personality traits of enlisted military men. Using a factorial study of the intercorrelations of various traits, he discovered that the two major dimensions of personality variation are:

1. Neuroticism (N)

2. Extraversion (E)

N and E are often referred to as “the big two.” Interestingly, these were the same personality dimensions that had already been described, at least theoretically, by earlier psychologists, such as Carl Jung. Indeed, research dating back to the 1930s by MacDougall and Thurstone had already demonstrated “five factors” of personality—a topic to which we will return in greater detail. But it was Eysenck who was first able to statistically show (based on data, not just theory) that there are two main human personality traits (N and E). For this his name has gone down in history as the foremost pioneer in modern personality research.

Figure 5.1 Plotting two different personality traits on an X-Y axis: neuroticism and extraversion.

It can be very helpful to plot personality on an X–Y axis. Let’s do that with neuroticism (N) and extraversion (E), as shown in Figure 5.1.

In brief, the trait of extraversion (denoted here by the X axis) refers to the speed at which someone experiences his emotional reactions, and in particular, positive emotions. Recollecting the bell-shaped curve we discussed earlier, we can divide the entire population into two groups: those who are on the right of the mean (extroverts) and those who are to the left of the mean (introverts).

What does it mean to be high in extraversion (E)? It does not simply mean someone who is the life of the party. It really refers to someone whose positive emotions, in response to triggers or various life stressors, come on very rapidly and likewise dissipate very rapidly. (Hence, these people are the life of the party because they quickly warm up to others around them.)

Extroverts also relate to the present implications of events. Thus, they often do not plan ahead or prepare for consequences. Basically they live in the moment. Extroverts tend to be more social, warm, and responsive to present life circumstances. Extroverts have an “external locus of control,” which basically means they look for external devices to make themselves happy (music, dancing, sports, other people, or perhaps more pathological external devices, such as drugs and alcohol). When things go wrong, extroverts tend to place external blame instead of taking personal responsibility.

Introverts, on the other hand, are low in extraversion (E). They tend to have slow, or even delayed, positive emotional responses to life events. They are more cool and slow to warm up in social situations. Their emotions come on gradually and also tend to leave that way. They have an “internal locus of control”: They tend to look more inside of themselves for the source of their happiness and meaning (prayer, meditation, contemplation). Also, introverts relate better to the future or past implications of events. They find it difficult to be living in the moment and can have trouble appreciating what is happening right now because of their propensity to overly focus on what happened in the past or what may happen in the future.

Extroverts are more influenced by rewards (that is, they respond well to positive feedback), while introverts are more influenced by punishments (they respond well to constructive criticism) and hence are more prompt in developing conditioned reflexes.

The neuroticism (N) dimension (denoted in Figure 5.1 by the Y axis), on the other hand, deals with the strength and depth of emotional reactions a person has to life stressors or triggers. It especially relates to negative emotions, including anger, anxiety, guilt, and depression. Emotionally, a more neurotic person responds intensely to life events, while the less neurotic responds weakly. To be sure, the words “neurotic,” “neurosis,” and “neuroticism” can be problematic. For one thing, the meaning of these terms has changed somewhat over the last century. Also, in the common vernacular the word neurotic often refers to more of a continual internal angst or anxiety, or a conflict-driven person. When hearing the word neurotic, people may summon up an image of Woody Allen, perpetually fidgety and flustered. But that is not quite what psychologists and psychiatrists currently mean when they use this word and its derivatives.

For instance, a highly neurotic person could be an emotionally stable person at baseline and under normal circumstances, but then dramatically come unglued under pressure. The neurotic, in the context of some life stressors, experiences strong emotional reactions (especially negative ones).

Let me paint a picture of an extreme neurotic. Imagine that an individual is driving along to work, feeling no particular emotions at all, when he comes to a stoplight and is suddenly rear-ended at low speed by a total stranger. In response to this episode of minor inconvenience, his emotions “explode” like a bomb with anger. He goes “ballistic” like a missile. He exits his vehicle screaming and yelling, hurling expletives, and fuming. In fact, so violently has his anger erupted that he’s not even able to perform the basic tasks that we all have been taught to do in this kind of fender-bender situation (pull to the side of the road, exchange insurance information, look for a witness, take a picture, and so on). His exaggerated emotional response is now impairing his ability to function properly and logically do the right thing. Immediately prior to the accident, this neurotic would have been totally logical and had good mental capacity, but now his emotions have totally overridden things. Until he calms down, this neurotic is going to make some mistakes and needs to be careful.

Take the same scenario, but imagine instead this time our driver is very low in neuroticism. Instead of flying off the handle, the driver gets out of his car cool, calm, and collected. He proceeds to do all the right things, very respectfully exchanging insurance information with the other driver and then goes on his way without even showing a sign of emotionality. His negative emotions are clearly more stable under stress.

For this reason we sometimes prefer to use the words “stable” and “unstable” when discussing the neuroticism personality dimension, although this designation might also imply that one side of the mean is “good” and the other side is “bad.”

The truth is (just as in the example of the seven-foot basketball player in Chapter 4) that there can actually be advantages to being a little “neurotic” in temperament. Likewise, being a little too “stable” can land you in hot water if you are not careful. So if, after you take a standardized personality test, you find out that you are on the “unstable and neurotic” side of this particular bell-shaped curve, remind yourself that, since half the human population is there too, it can’t be all bad.

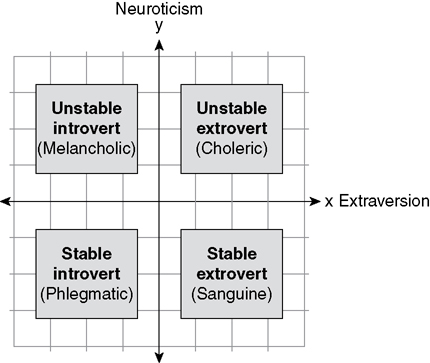

Here’s another important concept to register as you learn about personality. Traits such as extraversion and neuroticism are orthogonal. This means that your position on one of these personality dimensions has no bearing on and does not predict your position on any of the other dimensions. It also means that for any two dimensions being compared, they will divide a population of people into four separate groups, or subcategories (represented by each of the four quadrants on the graph shown in Figure 5.2). Hence, a person may fall into the “unstable (neurotic) extrovert” group, while someone else may be in the “stable introvert” group or one of the other groups represented by the other two quadrants. If fact, it turns out that the four quadrants delineated by these “big two” personality dimensions (neuroticism and extroversion) equate to the four main personality types first described by the ancient Greeks!

We come back soon to these “big two” dimensions (extraversion and neuroticism) in much more detail in subsequent chapters.

Figure 5.2 Four main personality groups are delineated by orthogonally plotting neuroticism versus extraversion on an X-Y axis.

Mental Edge Tips

- Be aware that statistical analysis shows that certain human personality traits are much more important and evident on a mathematical basis than others and that these traits apply to the entire population of human beings. We can plot them out on a bell-shaped curve, and for any one person we can measure how far away he or she is from the average (mean) score.

- Neuroticism and extraversion are the “big two” personality traits. And by plotting these traits on an X–Y axis, we obtain four personality types (one for each quadrant).

- Neuroticism refers to the strength of one’s emotional responses under stress, especially negative ones. Extraversion refers to the speed of one’s emotional responses, especially positive ones.

- There is no “right side” of the mean. Remind yourself again that the critical thing is how far away you are from the mean, and how you are dealing with it.