Risk aversion (along with its opposite, risk propensity) is a complex concept, in either psychology or finance. It can be either very fun or very dull to learn about. Go ahead and Google, “Arrow-Pratt Measure of Risk Aversion,” if you want a very dry, impractical, and (at least for your purposes) useless model of risk aversion.

In fact, we all intuitively know what risk aversion means. It refers to the process of making decisions after carefully weighing the risks and benefits associated with the choice. On one end of the spectrum, one person may need to be offered a huge reward to balance even the slightest amount of risk (this is somebody who is highly risk averse). Another person may take incredibly great risks in the hope of only a minimal benefit (a person with very low risk aversion). Most of us fall somewhere in between on the spectrum of risk aversion.

But risk aversion is actually a bit more complex than that. When it comes to risk-taking and the markets, there are two main forces (rewards) at play. First, there is the potential reward of making a monetary profit. Compared to safer (less volatile and less leveraged) financial investments, the futures markets offer speculators the chance to take greater risks in order to satisfy their greed (let’s call it what it is) for money and the nice things money can provide (better food, house, car, clothing, vacations, college education for children). The other potential “reward” in market trading is sensation-seeking: the thrill and excitement that trading itself can offer. These two rewards, making money and excitement-seeking, are not mutually exclusive. In and of themselves they are not necessarily bad. Although money is “the root of all evil,” it can also be the root of a lot of goodness.

these two basic rewards have been programmed into our genes and have been hardwired into our brains. After all, humans are a risk-taking species by nature. Our ancient ancestors originated in East Africa, and within a span of only 100,000 years (which, relatively speaking, is but a blink of the eye in terms of life on this planet) spread over the entire globe. How were our ancestors able to do it? Their “explorativeness” and willingness to take risks is likely one of the keys to the survival and thriving success of our species.

When you stop and think about it, the hunting of large and dangerous game by prehistoric men was a very risky endeavor. In comparison to their prey, our ancestors were small, slow, and had no built-in armor (tusks, thick skin, or the like) or other protective mechanisms (wings to fly away when things got dicey). Compared to market traders sitting behind their computer monitors, these were the real risk-takers! Certainly the huge success and globalization of the human species depended upon these hunters being smart and creative, which was determined by the superior size of their cerebral cortexes. But it still required a lot of risk-taking to make it work. The risks these ancient ancestors took were driven by a desire (greed) for a bigger hunk of meat, but equally so this dangerous hunting probably also provided a sense of thrill and excitement (“the chase,” “the adrenaline rush”). If there were no thrill or rush to the hunt, it’s possible our ancestors may have been satisfied with a life of gathering and eating fruits, nuts, and berries (like most other primates).

When we modern humans make financial or investment decisions and contemplate our own willingness to take on risk, we need to be aware that we do this both out of our propensity for greed and because we like the thrill or the rush of trading. (It’s very akin to sexual intimacy. If there were no thrill or rush, many humans might be less willing to take on the risk of being parents.) Again, it is built into us, and the two rewards (greed and thrill) are closely tied together.

That said, not everyone is amenable to the same degree of risk-taking. Risk-taking is a trait, and there is a wide variability (spectrum or dimension) to the extent people take risks. Futures traders clearly are, relatively speaking, financial risk-takers. They are willing to take longer odds in the hope of making bigger gains. More risk-averse investors, meanwhile, likely have all of their investments in mutual funds or exchange traded funds. The very risk-averse investor, of course, plops all of his or her money into a FDIC-insured savings accounts that pays 1 or 2 percent annual interest.

Further, some of us trade mostly for the prospect of making money (and the things money provides) and don’t get as much of a “high” from trading, while others primarily trade the markets because they get their kicks from the actual trading. Those in this second group are typically the unsuccessful traders and the people who develop addictions to trading the markets. (See Chapter 23 for more on the topic of addictions.)

Most of us probably take risks in trading because of a combination of the two rewards: It’s a chance to make money quickly, and there is some excitement associated with it. But be sure of this: Your average successful futures trader is not an extreme risk taker. The extreme risk taker is the person who gambles his last thin dime in Las Vegas at the roulette wheel, hoping and praying for a miracle.

Think about it: Markets can only go in one of three directions; they can go up, go down, or stay relatively flat. Compare that to how many different slots a roulette ball could land in (there are 38 slots on the American roulette wheel). And while the final outcome of the ball in the roulette wheel depends entirely on Lady Luck, trading the markets actually involves an incredible amount of knowledge, experience, insight, computational ability, planning, pattern recognition and judgment—along with a healthy portion of luck. Genuine market traders are speculators, not gamblers.

The word speculate comes from the Latin word speculatus, meaning “to spy out” and “to examine.” Traders are speculators in the sense that they are risk-takers, but they base their decisions on a lot of research, hard work, insight, and eventual understanding of various forces that drive the markets up and down.

There is no one facet on the NEO-AC that corresponds best to risk aversion versus risk-taking. Rather, research shows risk aversion can best be understood using a composite of several of the personality traits. A 2008 study1 published in Financial Services Review by Cliff Mayfield et al., for instance, found that there is a significant negative correlation between both openness (O) and extraversion (E) and investment-specific risk aversion. That is, people who are high in O and/or high in E are more likely to take risks with investments than people low in O and E. The study also found that personal characteristics influence investors’ perception of risk, and that their perception of risk was determining their investing behavior. As an example, they found that individuals who are more open to new experiences (high in O) tend to engage in long-term investing. However, one major shortcoming of this article was that it did not confirm that this kind of behavior was actually advantageous; that is, it did not confirm that people high in O actually are more successful in their investments by using a longer-term strategy.

A very large and detailed study2 of risk propensity was done by Nigel Nicholson and others at the London School of Business. Using NEO-AC data on 2,041 British financial traders (key point: they were not necessarily successful investors), risk aversion was measured across six different decision domains:

1. Recreational risks (rock-climbing, scuba diving)

2. Health risks (smoking, poor diet, excessive alcohol consumption)

3. Career risks (quitting a job without another to go to)

4. Financial risks (risky investments, gambling)

5. Safety risks (fast driving, motorcycling without a helmet)

6. Social risks (standing for election, publicly challenging a rule or decision)

This study found that a strong Big Five personality pattern emerges for people who are risk takers across all six of these domains: They are high in both E and O and low in N, A, and C. The authors of the study also found, however, that risk-taking is not quite the same across all six decision domains. As an example, there are big reductions over a person’s lifetime in recreational, health, and safety risk-taking behaviors, while there are relatively small reductions or even no changes in career, financial, or social risk-taking behaviors across one’s lifetime. Although the researchers did not speculate on the reason for this discrepancy in risky behaviors, I would propose that it relates to the underlying reason for the risky behaviors. Safety risks, such as racing a motorcycle down the freeway, are more about getting the adrenaline rush going, and there is little other gain or motivation for it. Social and financial risks, on the other hand, involve taking the specified risk with the hope and knowledge that something good and tangible will come of it, something that will make the risk worthwhile.

But we are especially interested in knowing if there is a identifiable personality profile for people who take risks more for the thrill of it versus people who take risks more because they are hoping to get something out of it (greed). Further, is there a different personality profile for traders who go on to develop an addiction to trading compared to people who do not?

On the facet level, Nicholson found that high E5 (excitement-seeking) and high O6 (openness to values) were the greatest predictors of risk-taking in all six of the decision domains as well as in overall risk-taking. Nicholson theorized that high E (especially excitement seeking) and high O supply the “motivational force” for people to take risks, while low N and low A insulate risk takers from concern over negative consequences, and low C lowers the cognitive barriers to taking risks. Nicholson assumes that people low in C will attempt to secure various benefits (monetary or otherwise) by taking risks compared to those high in C, who will pursue the same benefits through disciplined striving, rather than risk-taking.

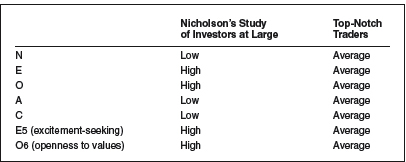

So let’s see how the investors in Nicholson’s study stack up against our top-notch futures traders in Table 16.1.

TABLE 16.1

Comparison of Risk-Taking Traits in Investors at Large Versus Our Top-Notch Traders

So what’s going on here? Is it that futures traders don’t take risks? Not likely. Or is it that successful futures traders, that is, those we tested, are not high-risk individuals? The fact that a high E5 (excitement-seeking) was the most important facet score in determining risk-taking behavior in Nicholson’s study, whereas our cohort of successful futures traders had an average E5 score, says a lot. It tells me that the thrill factor, as a reason for trading, is less important to the successful trader than it is to the average investor. Monetary rewards and likely other psychological rewards and benefits are driving the successful traders. Also, I think that our successful futures traders are not transsituational risk-takers.

Further, the average N and A scores support the notion that our successful traders are better equipped compared to average traders, who have low N and A, to be aware of potential negative consequences associated with risk taking. Those who are low in certain N and A facets don’t possess fear. Fear is good. It’s healthy. Not too much, of course, just enough fear to keep you out of harm’s way. And the successful traders have that.

Don’t confuse fear with anxiety here. When I say successful traders have a healthy dose of fear, I am referring to their C1 facet scores, which are discussed in the next chapter.

Also, the average C score of the successful trader indicates that he or she remains disciplined and works hard and diligently at this very risky endeavor. He or she applies controlled efforts to master the art of trading. Conversely, people with low overall C are more susceptible to “get rich quick” behaviors; that is, they attempt to cut corners, find the easy way instead of the right way, and so forth.

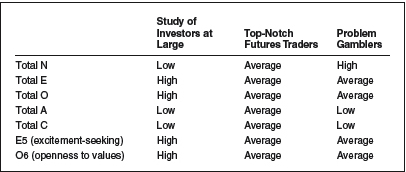

Further interesting comparisons can be made with the personality traits of problem gamblers, a topic of numerous research studies. (See Table 16.2.) You will note that, like the risk takers in Nicholson’s study of investors at large, problem gamblers have low A and low C, but they are high N (especially impulsivity, N5).

Although the column in Table 16.2 under “Top-Notch Futures Traders” reads “average” right on down the line, it is important to keep in mind that there is a degree of variability in some of the facets, and after detailed interviewing with these traders, some patterns emerged. For example, there is great deal of variability in the O4, O5, and O6 scores of successful traders, and from our discussions with these traders a trend seems to emerge. Traders who are high in O5 (ideas) or O6 (values) seem to be especially motivated to get involved in futures trading, not for a rush or thrill, but for a deeper psychological need. That is, they truly enjoy the challenge of learning and mastering something very difficult. Don’t get me wrong, the primary reason they are doing it is to make money (greed). But the pursuit of mastery is also very tempting and very rewarding to them as well.

TABLE 16.2

Personality Comparisons between Investors at Large, Successful Futures Traders, and Problem Gamblers

Interestingly, our discussions with traders find that the O4 (actions) facet of the NEO-AC seems to measure a trader’s level of greed pretty well. O4 is a barometer, not just for the psychological greed or lust of wealth, but also for the actual decision to pursue it. Those who trade first and foremost to find “a bigger hunk of meat” have higher O4 scores. They are willing to go out on a limb (the action) and do something they have never done before in order to haul in a big financial reward. They climb out on the limb, not because of the thrill in tempting the branch to see if it will bear their weight, but because they are in pursuit of some treasured fruit they hope will be found growing at the end of the limb. They take the risk despite the possibility that the branch may break, not because of it. (Keep in mind that for many, if not most, people there are components of both thrill and greed in their risk-taking behaviors. So relatively speaking, “high O4” traders are greedier and less thrill-seeking.)

We already described in detail how greed can be a good thing and how it is even an innate quality that is built into the human species. However, too much of anything (yes, even oxygen) can be bad and potentially lethal. Life and successful living is all about balance. There is a tendency for many aspiring futures traders to be high in O4/greed. My father’s way of putting it is, “traders have bigger greed glands than others.”

Being excessively greedy can clearly be a very unhealthy thing. Going too far out on too thin a limb in search of riper fruit can be very hazardous to your health. While we all have some degree of greed, we need to learn to temper our greed with an appreciation for what we have in our lives. If this greed is not controlled or managed properly, it will surely lead to a trader’s downfall. It is important to recognize and learn to live with your greed, and neither deny it nor exploit it. Our successful traders who are high in O4 have learned to do that. We’ll get back to this in a moment.

Since most legitimate futures traders are not trading the markets purely to get a rush (the way someone gets a rush from driving fast when there is no need or benefit to doing so), the rest of this chapter will discuss risk-taking from the perspective of how high someone scores on the facets O4 to O6. Keep in mind, though, that the other risk-aversion facets, especially E5, can be equally wrapped up in how risky your trading habits may be or become. In general, we have found that the higher your O4, O5, and O6 scores, the less risk averse you are (more willing to take risks), while, conversely, someone with very low O4 to O6 scores is someone who is very risk averse (tends to avoid taking risks). Interestingly, we found successful futures traders all along this spectrum, from high to low risk aversion.

A risk-averse market trader (lower O4 to O6) is going to have difficulty tolerating the concept of larger losses. This person is, from a personality standpoint, much more suited to smaller, more frequent and more controlled trades. Trading in smaller time frames is also more appropriate for these traders, as they are not people who are looking for big and protracted market runs. They are looking to pinpoint the smaller market moves that come and go more frequently. Using smaller time frames allows such a trader to control risk with the holding period.

An effective strategy for these traders is to use very tight stops. That is to say, these are people who will benefit from very close money management. They should more frequently monitor how the market is doing so that they can adjust their stops and positions as needed. These are not people who should enter a position and then go on a long vacation to a remote tropical island where they will have no ability to monitor and manage their risks.

A good analogy here is surfing. Risk-averse traders are those surfers who are looking for the more frequent and reliable, albeit smaller, wave breaks. At the end of the surfing day, they would rather have mounted and ridden many small or medium-sized waves as opposed to waiting for one giant wave.

In comparison, low risk-averse traders (high O4 to O6) hope to catch the mammoth waves; they are more than happy to let the routine, mundane (to them) waves go by as they seek out that monster ride. They have a tolerance for taking such risks.

If you are a relatively risk-adverse market trader, as you are paddling out to where the waves are breaking, pay close attention to where and how the swells are forming (that is, how the markets are moving). Only stand up on your surfboard and ride those waves that you can see and feel are going to be a size to your liking. If you see a potentially huge wave forming or great instability developing in the markets, be careful not to be tricked into riding it (particularly if you also scored high in N5—impulsivity!), as your level of risk aversion is likely ill-prepared for such a ride.

No matter how tempting it looks, it’s probably best if you keep your tummy and head flat on your surfboard and let that giant wave go right on by you. Let the big-wave surfers get their kicks on those giant 30-foot swells—and potentially crash spectacularly into the reef and rocks. Reassure yourself that surely there will be plenty more 7-foot waves yet to come that are more your style and more to your liking. The risk-averse traders are going to be challenged during periods of high market volatility, and it is best for them to stay on the sidelines during those times.

A trader who is less risk averse (high O4 to O6), on the other hand, is someone who is drawn to the possibility of larger wins, with the full understanding that there could be greater drawdowns, bumps, and bruises along the way. They are willing to take big risks in hopes of cashing in on big returns. These traders enjoy the stimulation and challenge of taking bigger risks: They seek them out and even thrive on them!

These are the surfers who, with glee, head to the North Shore of Oahu in late December because they know that’s when and where the big waves are rolling in! They are better suited for taking on larger positions (large relative to the size of their own investment portfolio, not necessarily large in comparison to that of another trader). Trading too small a position (small waves) has the potential to lull the risk-taking trader to sleep. She may lose focus and may potentially make bad decisions simply because she is not paying close enough attention to her positions There is not enough at stake for her to really take interest—at least not until she realizes the trade has gone bust.

Bigger risk-takers are also better at holding onto their positions for longer periods of times. They are able to tolerate the intra-trade instability that is sure to be present. Big bull and bear moves in the market are never arrows that go straight up or straight down. High O4 to O6 traders are better able to ride out the instability and ups and downs that comprise the overall market swing. Their stops can and should be looser.

Risk-taking traders (and especially those who are also high on the N5, impulsivity, scale), should take great care not to enter the market during a period of low volatility. If there are no huge swells forming right now, don’t be tempted to ride the smaller waves just to pass the time or because you are bored. If you do fall into this trap, you can be sure the next big market move is going to start forming at a time when you are not ready to put your full concentration on it. Or you may miss it outright, simply because the small wave distracted you from seeing the big one that is forming. Keep in mind, too, that different markets are historically more prone to volatility than others. Depending on your risk-aversion score, you may fair better in one market over another. Find a surfing location that matches your level of risk aversion.

If you are high in O (again, especially O4 to O6), high in E5 (excitement seeking), as well as high in N, you need to especially watch out for the following common personality trap. Your penchant for excitement and thrills may entice you to make a trade, not because it is the wise thing to do, but because you are looking for a way to instill some action or stimulation in your life. Then, once realizing it was a mistake and that you are in over your head, you panic. Your neuroticism kicks in after one or several losing, high-risk trades. Now, not for excitement seeking, but purely out of anger, anxiety, guilt, depression, or impulsiveness, you make yet another bad decision, which only compounds your loses.

Here’s one final learning point about risk aversion. While innate personality has a lot to do with a person’s risk aversion or risk-taking behavior, it likely is not the whole story. In 2006 researchers at University Hospital Zurich’s Key Brain-Mind Research Center demonstrated3 that risk-taking can potentially be a modifiable behavior. They used low-frequency, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to transiently disrupt the function of a part of the brain’s cortex called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in a group of normal people. They then applied a well known gambling paradigm that provides a measure of decision making under risk. Individuals displayed significantly riskier decision making after disruption of the right, but not the left, DLPFC. These findings suggest that the right DLPFC plays a crucial role in the suppression of superficially seductive options and risk taking. So it appears that this fundamental human capacity, risk taking, can actually be manipulated in normal subjects through cortical stimulation.

Why is this research result potentially important for you? After all, although TMS has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of refractory depression and other mood disorders, it is unlikely that most market traders will ever have their right DLPFC stimulated by a giant magnet. The message to take away is that risk aversion may not be as immutable as was once thought. In fact, I am sure we all know people (if not ourselves) who took bigger risks in their early adult years, only to become more risk-averse as they grew older.

Not only that, but there is also now research showing that risk-aversion behavior can actually change during cyclical patterns in the market. For example, a 2009 research study4 by Daniel Smith and Robert Whitelaw gave us for the first time hard evidence that levels of risk aversion in investors increase during times of economic contractions. This makes intuitive and theoretical sense. (Yet another body of research shows that an individual’s own personal wealth, regardless of size, will not change his level of risk aversion—a rich investor’s risk aversion will not increase or decrease if he loses his personal fortune.)

The point is, risk aversion is not necessarily static, and it is important to monitor one’s own level of risk aversion and be aware that it may change over time or during certain market conditions. If and when your level of risk aversion changes, you should adapt your market strategies accordingly.

Mental Edge Tips

- Openness facets O4, O5, and O6 correspond well to risk aversion, especially the greed component of it.

- You can be a successful market trader regardless of whether your O facets are high or low. The key is that you need to identify trading strategies that match your level of risk aversion. Successful traders look for market volatility that matches their personalities.

- Expected duration of trade, placing appropriate stops, and relative size of trades to one’s overall portfolio are also crucial keys to matching risk aversion to trading.