After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. describe what sport and exercise psychology is,

2. understand what sport and exercise psychology specialists do,

3. know what training is required of a sport and exercise psychologist,

4. understand major developments in the history of sport and exercise psychology,

5. distinguish between scientific and professional practice knowledge,

6. integrate experiential and scientific knowledge,

7. compare and contrast orientations to the field, and

8. describe career opportunities and future directions in the field.

Jeff, the point guard on the high school basketball team, becomes overly nervous in competition. The more critical the situation, the more nervous he becomes and the worse he plays. Your biggest coaching challenge this season will be helping Jeff learn to manage stress.

Beth, fitness director for the St. Peter’s Hospital Cardiac Rehabilitation Center, runs an aerobic fitness program for recovering patients. She is concerned, however, because some clients don’t stick with their exercise programs after they start feeling better.

Mario has wanted to be a physical educator ever since he can remember. He feels frustrated now, however, because his high school students have so little interest in learning lifelong fitness skills. Mario’s goal is to get the sedentary students motivated to engage in fitness activities.

Patty is the head athletic trainer at Campbell State College. The school’s star running back, Tyler Peete, has achieved a 99% physical recovery from knee surgery. The coaches notice, however, that in practices he still favors his formerly injured knee and is hesitant when making cutbacks. Patty knows that Tyler is physically recovered but needs to regain his confidence.

Tom, a sport psychologist and longtime baseball fan, just heard about his dream position, a consulting job. The owners of the Chicago Cubs, fed up with the team’s lack of cohesion, have asked him to quickly design a training program in psychological skills. If Tom can construct a strong program in the next week, he will be hired as the team’s sport psychology consultant.

If you become a coach, an exercise leader, a physical educator, an athletic trainer, or even a sport psychologist, you also will encounter the kinds of situations that Jeff, Beth, Mario, Patty, and Tom face. Sport and exercise psychology offers a resource for solving such problems and many other practical concerns. In this chapter you will be introduced to this exciting area of study and will learn how sport and exercise psychology can help you solve practical problems.

Defining Sport and Exercise Psychology

Sport and exercise psychology is the scientific study of people and their behaviors in sport and exercise contexts and the practical application of that knowledge (Gill & Williams, 2008). Sport and exercise psychologists identify principles and guidelines that professionals can use to help adults and children participate in and benefit from sport and exercise activities.

Most people study sport and exercise psychology with two objectives in mind: (a) to understand how psychological factors affect an individual’s physical performance and (b) to understand how participation in sport and exercise affects a person’s psychological development, health, and well-being. They pursue this study by asking the following kinds of questions:

Objective A: Understand the effects of psychological factors on physical or motor performance

Objective B: Understand the effects of physical activity participation on psychological development, health, and well-being

Sport psychology applies to a broad population base. Although some professionals use sport psychology to help elite athletes achieve peak performance, many other sport psychologists are concerned more with children, persons who are physically or mentally disabled, seniors, and average participants. More and more sport psychologists have focused on the psychological factors involved in exercise, developing strategies to encourage sedentary people to exercise or assessing the effectiveness of exercise as a treatment for depression. To reflect this broadening of interests, the field is now called sport and exercise psychology, and some individuals focus only on the exercise aspects of the field.

Specializing in Sport Psychology

Contemporary sport psychologists pursue varied careers. They serve three primary roles in their professional activities: conducting research, teaching, and consulting (see figure 1.1). We’ll discuss each of these briefly.

Research Role

A primary function of participants in any scholarly field is to advance the knowledge within the field by conducting research. Most sport and exercise psychologists in a university conduct research. They might, for example, study what motivates children to be involved in youth sport, how imagery influences proficiency in golf putting, how running for 20 minutes four times a week affects an exerciser’s anxiety levels, or what the relationship is between movement education and self-concept among elementary physical education students. Today, sport and exercise psychologists are members of multidisciplinary research teams that study problems such as exercise adherence, the psychology of athletic injuries, and the role of exercise in the treatment of HIV. Sport psychologists then share their findings with colleagues and participants in the field. This sharing produces advances, discussion, and healthy debate at professional meetings and in journals (see “Leading Sport and Exercise Psychology Organizations and Journals” on page 6).

Teaching Role

Many sport and exercise psychology specialists teach university courses such as exercise psychology, applied sport psychology, and the social psychology of sport. These specialists may also teach such courses as personality psychology or developmental psychology if they work in a psychology department, or courses such as motor learning and control or sport sociology if they work in a sport science program.

Consulting Role

A third important role is consulting with individual athletes or athletic teams to develop psychological skills for enhancing competitive performance and training. In fact, Olympic Committees and some major universities employ full-time sport psychology consultants, and hundreds of other teams and athletes use consultants on a part-time basis for psychological skills training. Many sport psychology consultants work with coaches through clinics and workshops.

Some sport and exercise psychologists now work in the fitness industry, designing exercise programs to maximize participation and promote psychological and physical well-being. Some consultants work as adjuncts to support a sports medicine or physical therapy clinic, providing psychological services to injured athletes.

Distinguishing Between Two Specialties

A significant distinction in contemporary sport psychology exists between two types of specialties: clinical sport psychology and educational sport psychology. Next we discuss the distinction between these two specialties and the training needed for each.

Clinical Sport Psychology

Clinical sport psychologists have extensive training in psychology so they can detect and treat individuals with emotional disorders (e.g., severe depression, suicidal tendencies). Licensed by state boards to treat individuals with emotional disorders, clinical sport psychologists have received additional training in sport and exercise psychology and the sport sciences. Clinical sport psychologists are needed because, just as in the normal population, some athletes and exercisers develop severe emotional disorders and require special treatment (Brewer & Petrie, 2002). Eating disorders and substance abuse are two areas in which a clinical sport psychologist can often help sport and exercise participants.

Educational Sport Psychology

Educational sport psychology specialists have extensive training in sport and exercise science, physical education, and kinesiology; and they understand the psychology of human movement, particularly as it relates to sport and exercise contexts. These specialists often have taken advanced graduate training in psychology and counseling. They are not trained to treat individuals with emotional disorders, however, nor are they licensed psychologists.

A good way to think of an educational sport psychology specialist is as a “mental coach” who, through group and individual sessions, educates athletes and exercisers about psychological skills and their development. Anxiety management, confidence development, and improved communication are some of the areas that educational sport psychology specialists address. When an educational sport psychology consultant encounters an athlete with an emotional disorder, he or she refers the athlete to either a licensed clinical psychologist or, preferably, a clinical sport psychologist for treatment.

Both clinical and educational sport and exercise psychology specialists must have a thorough knowledge of both psychology and exercise and sport science (see figure 1.2). In 1991, the AASP began a certified consultant program. To qualify for certification as sport and exercise consultants, people must have advanced training in both psychology and the sport sciences. This requirement is designed to protect the public from unqualified individuals professing to be sport and exercise psychologists.

Leading Sport and Exercise Psychology Organizations and Journals

Organizations

Journals

Reviewing the History of Sport and Exercise Psychology

Today, sport and exercise psychology is more popular than ever before. It is a mistake, however, to think that this field has developed only recently. Sport psychology dates back to the turn of the 20th century in the United States (Wiggins, 1984). Its history falls into six periods, which are highlighted here along with some specific individuals and events from each period. These various periods have distinct characteristics and yet are interrelated. Together they contributed to the field’s development and growing stature.

Period 1: Early Years (1893–1920)

In North America, sport psychology began in the 1890s. Norman Triplett, a psychologist from Indiana University and a bicycle racing enthusiast, wanted to understand why cyclists sometimes rode faster when they raced in groups or pairs than when they rode alone (Triplett, 1898). First, he verified that his initial observations were correct by studying cycling racing records. To test his hunch further, he also conducted an experiment in which young children were to reel in fishing line as fast as they could. Triplett found that children reeled in more line when they worked in the presence of another child. This experiment allowed him to make more reliable predictions about when bicycle racers would have better performances.

Another early pioneer was E.W. Scripture, a Yale psychologist who was interested in taking a more scientific data-based approach to the study of psychology, as much of the psychology in these early years was introspective and philosophical (see Kornspan, 2007, for an in-depth examination of his work). Scripture saw sport as an excellent way to demonstrate the value of this “new” scientific psychology and with his students conducted a number of laboratory studies on reaction and muscle movement times of fencers and runners, as well as transfer of physical training. Scripture also discussed early research examining how sport might develop character in participants. Most interesting was the fact that Scripture worked closely with William Anderson of Yale, one of the first physical educators in America. This demonstrates that those in the fields of physical education and psychology worked together to develop sport psychology.

In these early years, psychologists and physical educators were only beginning to explore psychological aspects of sport and motor skill learning. They measured athletes’ reaction times, studied how people learn sport skills, and discussed the role of sport in personality and character development; but they did little to apply these studies. Moreover, people dabbled in sport psychology, but no one specialized in the field.

Highlights

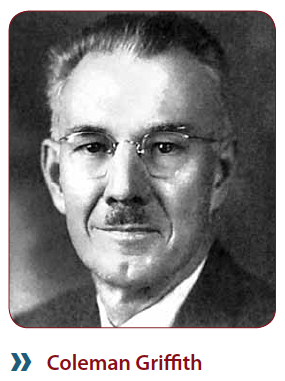

Period 2: Griffith Era (1921–1938)

Coleman Griffith was the first North American to devote a significant portion of his career to sport psychology, and today he is regarded as the father of American sport psychology (Kroll & Lewis, 1970). A University of Illinois psychologist who also worked in the Department of Physical Welfare (Physical Education and Athletics), Griffith developed the first laboratory in sport psychology, helped initiate one of the first coaching schools in America, and wrote two classic books, Psychology of Coaching and Psychology of Athletics. He also conducted a series of studies on the Chicago Cubs baseball team and developed psychological profiles of such legendary players as Dizzy Dean. He corresponded with Notre Dame football coach Knute Rockne about how best to psych teams up and questioned Hall of Famer Red Grange about his thoughts while running the football. Ahead of his time, Griffith worked in relative isolation, but his high-quality research and deep commitment to improving practices remain an excellent model for sport and exercise psychologists.

Highlights

Period 3: Preparation for the Future (1939–1965)

Franklin Henry at the University of California, Berkeley, was largely responsible for the field’s scientific development. He devoted his career to the scholarly study of the psychological aspects of sport and motor skill acquisition. Most important, Henry trained many other energetic physical educators who later became university professors and initiated systematic research programs. Some of his students became administrators who reshaped curriculums and developed sport and exercise science or the field of kinesiology as we know it today.

Other investigators from 1939 to 1965, such as Warren Johnson and Arthur Slatter-Hammel, helped lay the groundwork for future study of sport psychology. They helped create the academic discipline of exercise and sport science; however, applied work in sport psychology was still limited.

One exception to the limited application of sport psychology occurring during this era was the work of Dorothy Hazeltine Yates, one of the first women in the United States to both practice sport psychology and conduct research. Yates consulted with university boxers, teaching them how to use relaxation and positive affirmations to help them manage emotions and enhance performance (Kornspan & MacCracken, 2001). The technique, called the relaxation-set method, was developed by Yates during World War II when she consulted with a college boxing team with considerable success. She later taught a psychology course exclusively for athletes and aviators. Like many of today’s sport psychologists, Yates was interested in scientifically determining if her interventions were effective, and she published an experimental test of her technique with boxers (Yates, 1943). While she did her work in relative isolation, Yates’ research on practice orientation was especially impressive.

Highlights

Period 4: Establishment of Academic Sport Psychology (1966–1977)

By the mid-1960s, physical education had become an academic discipline (now called kinesiology or exercise and sport science), and sport psychology had become a separate component within this discipline, distinct from motor learning. Motor learning specialists focused on how people acquire motor skills (not necessarily sport skills) and on conditions of practice,

feedback, and timing. In contrast, sport psychologists studied how psychological factors—anxiety, self-esteem, and personality—influence sport and motor skill performance and how participation in sport and physical education influences psychological development (e.g., personality, aggression).

Applied sport psychology consultants also began working with athletes and teams. Bruce Ogilvie of San Jose State University was one of the first to do so, and he is often called the father of North American applied sport psychology. Concurrent with the increased interest in the field, the first sport psychology societies were established in North America.

Highlights

Period 5: Multidisciplinary Science and Practice in Sport and Exercise Psychology (1978–2000)

From the mid-1970s to 2000, tremendous growth in sport and exercise psychology took place, both in North America and internationally. The field became more accepted and respected by the public. Interest in applied issues characterized this period, as did the growth and development of exercise psychology as a specialty area for researchers and practitioners. Sport and exercise psychology also separated from the other psychologically related exercise and sport science specializations of motor learning and control and motor development. More and better research was conducted, and this research was met with increased respect and acceptance in related fields such as psychology. Alternative forms of qualitative and interpretive research emerged and became better accepted as the period came to a close. Specialty journals and conferences in the area were developed, and numerous books were published. Both students and professionals with backgrounds in general psychology entered the field in greater numbers. Training in the field took a more multidisciplinary perspective as students took more counseling- and psychology-related course work. The field wrestled with a variety of professional practice issues such as defining training standards for those in the area, developing ethical standards, establishing licensure, and developing full-time positions for the increasing numbers of individuals entering the field.

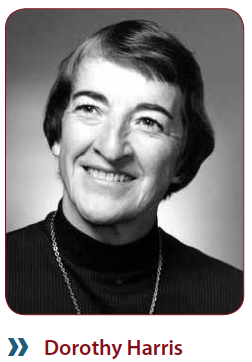

In this period, Dorothy Harris, a professor at Pennsylvania State University, advanced the cause of both women and sport psychology. She helped establish the PSU graduate program in sport psychology. Her accomplishments included being the first American and the first woman member of the International Society of Sport Psychology, the first woman to be awarded a Fulbright Fellowship in sport psychology, and the first woman president of the North American Society of Sport Psychology and Physical Activity. Harris broke ground for future women to follow at a time where few women were professors in the field.

Highlights

Period 6: Contemporary Sport and Exercise Psychology

(2001–Present)

Today sport and exercise psychology is a vibrant and exciting field with a bright future. However, some serious issues must be addressed. Later in this chapter you will learn about contemporary sport and exercise psychology in detail, but some of the key developments are highlighted here.

Highlights

Women in Sport and Exercise Psychology

When one looks at the history of sport and exercise psychology one is struck by the absence of women. This is not uncommon in the history of many sciences, and there are multiple factors that account for this absence. Historically, women were not given the same equal opportunities as their male counterparts. In addition, those women who were involved often had to overcome prejudices and other major obstacles to professional advancement. Finally, women’s contributions have often been under reported in scientific history.

In some excellent developments, Kornspan and MacCracken (2001) identified the important research, teaching, and intervention work Dorothy Hazeltine Yates completed in the 1940s, and the work of Dorothy Harris has also been acknowledged. Vealey (2006), in providing a comprehensive history of the evolution of sport and exercise psychology, has also uncovered some previously ignored contributions of women pioneers in the field. Lastly, Krane and Whaley (in press) and Whaley and Krane (in press) have also conducted a study of eight U.S. women who greatly influenced the development of the field over the last 30 years. These included Joan Duda, Deb Feltz, Diane Gill, Penny McCullagh, Carole Oglesby, Tara Scanlan, Maureen Weiss, and Jean Williams. These women were characterized by a number of common characteristics (e.g., driven, humble, competent, passionate about the field) and helped shape the field by mentoring countless male and female students, producing top notch lines of research, and providing caring, competent leadership (Krane & Whaley, in press). They also faced numerous challenges in their trailblazing efforts such as overcoming department politics and sexism (Whaley & Krane, in press). However, their “quiet competence” prevailed, and these outstanding women have contributed greatly to the history of U.S. sport and exercise psychology.

Finally, contributions of women to sport and exercise psychology are not limited to the United States. Women from around the world, like Russian Natalia Stambulova, German-born Dorothea Alfermann, and Spaniard Gloria Balague, have made important contributions to the field for multiple decades.

One thing is clear. While they may not have been given the credit they have deserved, women have greatly contributed to the development of sport psychology and exercise psychology and are helping drive major advances in the field today.

Focusing on Sport and Exercise Psychology Around the World

Sport and exercise psychology thrives worldwide. Sport psychology specialists work in over 70 different countries. Most of these specialists live in North America and Europe; and major increases in activity have also occurred in Latin America, Asia, and Africa in the last decade.

Sport psychologists in Russia and Germany began working at about the time Coleman Griffith began his work at the University of Illinois. For example, the pioneering work of Russian sport psychologist Avksenty Puni has recently been disseminated to English-speaking audiences and provides a fascinating glimpse of this individual’s 50 year career (Ryba, Stambulova, & Wrisberg, 2005; Stambulova, Wrisberg, & Ryba, 2006). Puni’s theorizing on psychological preparation for athletic competition focusing on realistic goals, uncompromising effort, optimal emotional arousal, high tolerance for distractions and stress, and self-regulation was groundbreaking and far ahead of what was being done in North America at the time. His work certainly demonstrates the importance of looking outside one’s borders for sport psychology knowledge.

The International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) was established in 1965 to promote and disseminate information about sport psychology throughout the world. ISSP has sponsored 12 World Congresses of Sport Psychology—focusing on such topics as human performance, personality, motor learning, wellness and exercise, and coaching psychology—that have been instrumental in promoting awareness of and interest in the field. Since 1970, ISSP has also sponsored the International Journal of Sport Psychology (IJSP).

Credit for much of the international development of sport psychology goes to Italian sport psychologist Ferruccio Antonelli, who was both the first president of ISSP and the first editor of IJSP. Sport and exercise psychology is now well recognized throughout the world as both an academic area of concentration and a profession. The prospect of continued growth remains bright.

Bridging Science and Practice

Reading a sport and exercise psychology textbook and actually working professionally with exercisers and athletes are very different activities. To understand the relationship between the two, you must be able to integrate scientific textbook knowledge (scientifically derived knowledge) with practical experience (professional practice knowledge). We will help you develop the skills to do this so you can better use sport and exercise psychology knowledge in the field.

Scientifically Derived Knowledge

Sport and exercise psychology is above all a science. Hence, it is important that you understand how scientifically derived knowledge comes about and how it works; that is, you need to understand the scientific method. Science is dynamic—something that scientists do (Kerlinger, 1973). Science is not simply an accumulation of facts discovered through detailed observations but rather a process, or method, of learning about the world through the systematic, controlled, empirical, and critical filtering of knowledge acquired through experience. When we apply science to psychology, the goals are to describe, explain, predict, and allow control of behavior.

Let’s take an example. Dr. Jennifer Jones, a sport psychology researcher, wants to study how movement education affects children’s self-esteem. Dr. Jones first defines self-esteem and movement education and determines what age groups and particular children she wants to study. She then explains why she expects movement education and self-esteem to be related (e.g., the children would get recognition and praise for learning new skills). Dr. Jones’ research is really about prediction and control: She wants to show that using movement education in similar conditions will consistently affect children’s self-esteem in the same way. To test such things, science has evolved some general guidelines for research:

1. The scientific method dictates a systematic approach to studying a question. It involves standardizing the conditions; for example, one might assess the children’s self-esteem under identical conditions with a carefully designed measure.

2. The scientific method involves control of conditions. Key variables, or elements in the research (e.g., movement education or changes in self-esteem), are the focus of study, with other variables controlled (e.g., the same person doing the teaching) so they do not influence the primary relationship.

3. The scientific method is empirical, which means it is based on observation. Objective evidence must support beliefs, and this evidence must be open to outside evaluation and observation.

4. The scientific method is critical, meaning that it involves rigorous evaluation by the researcher and other scientists. Critical analysis of ideas and work helps ensure that conclusions are reliable.

Theory

A scientist’s ultimate goal is a theory, or a set of interrelated facts that present a systematic view of some phenomenon in order to describe, explain, and predict its future occurrences. Theory allows scientists to organize and explain large numbers of facts in a pattern that helps others understand them. Theory then turns to practice.

One example is the social facilitation theory (Zajonc, 1965). After Norman Triplett’s first reel-winding experiment with children (see earlier section, “Reviewing the History of Sport and Exercise Psychology”), psychologists studied how the presence of an audience affects performance, but their results were inconsistent. Sometimes people performed better in front of an audience, and other times they performed worse. Zajonc saw a pattern in the seemingly random results and formulated a theory. He noticed that when people performed simple tasks or jobs they knew well, having an audience influenced their performance positively. However, when people performed unfamiliar or complex tasks, having an audience harmed performance. In his social facilitation theory, Zajonc contended that an audience creates arousal in the performer, which hurts performance on difficult tasks that have not been learned (or learned well) and helps performance on well-learned tasks.

Zajonc’s theory increased our understanding of how audiences influence performance at many levels (students and professionals) and in many situations (sport, exercise). He consolidated many seemingly random instances into a theory basic enough for performers, coaches, and teachers to remember and to apply in a variety of circumstances. As the saying goes, nothing is more practical than a good

theory!

Of course, not all theories are equally useful. Some are in early stages of development, and others have already passed the test of time. Some theories have a limited scope and others a broad range of application. Some involve few variables and others a complex matrix of variables and behaviors.

Studies Versus Experiments

An important way in which scientists build, support, or refute theory is by conducting studies and experiments. A study involves an investigator’s observing or assessing factors without changing the environment in any way. For example, a study comparing the effectiveness of goal setting, imagery, and self-talk in improving athletic performance might use a written questionnaire given to a sample of high school cross country runners just before a race. The researchers could compare techniques used by the fastest 20 runners with those used by the slowest 20 runners. The researchers would not be changing or manipulating any factors but simply observing whether faster runners reported using particular mental skills (e.g., imagery). But the researchers would not know whether the goal setting, imagery, and self-talk caused some runners to go faster or whether running faster stirred the runners to set more goals. Studies have limited ability to identify what scientists call causal (cause and effect) relations between factors.

![]()

Coming Off the Bench: A Sport Psychology Consulting Case Study

Jerry Reynolds was referred to Ron Hoffman, Southeastern University sport psychology consultant, at the end of his freshman year of varsity basketball. Jerry had had a successful high school career, lettering in three sports and starting every basketball game. On a full scholarship at Southeastern, Jerry worked harder than anyone else on the team and improved his skills. Still, he did not make the starting five. In the second half of the season’s first contest, Coach Johnson put Jerry into the game. As he moved to the scorer’s table and awaited the substitution whistle, Jerry found that he was much more nervous than ever before. His heart was pounding, and he could not shut off the chatter in his mind. He entered the game and had a disastrous performance. He threw the ball away several times, picked up two silly fouls, and failed to take an open shot. Coach Johnson took Jerry out. After the game, Jerry’s coaches and teammates told him it was just nerves and to relax. But Jerry could not relax, and a pattern of high anxiety and deteriorating performance ensued. After a few more disasters, Jerry rode the bench for the remainder of the season.

Jerry hesitated to see a sport psychologist. He did not think he was mentally ill, and he was somewhat embarrassed about the idea of seeing a “shrink.” Much to Jerry’s surprise, Dr. Hoffman was a regular guy who talked a lot like a coach, so Jerry agreed to meet with him every couple of weeks.

Working with Dr. Hoffman, Jerry learned it was common to experience anxiety when making the transition from high school to college ball. After all, 90% of the players he had defeated in high school were no longer competing. Hoffman also pointed out that after Jerry had started for 3 years in high school, it was no surprise if he had a hard time adjusting to coming off the bench and entering a game cold. He was experiencing a new kind of pressure, and his response to the pressure—his nervousness—was to be expected.

Dr. Hoffman taught Jerry how to relax by using a breathing technique called centering. He taught Jerry to control negative thoughts and worries by stopping them with an image and replacing them with more positive affirmations. Jerry developed a mental preparation routine for coming off the bench, including stretches to keep loose and a procedure to help him focus as he waited at the scorer’s table.

Jerry practiced these psychological techniques extensively in the off-season and refined them during early-season practices and scrimmages. After he was able to come off the bench without falling apart, he worked on taking open shots and quickly resumed playing to his full potential.

That season Jerry accomplished his goal of coming off the bench and helping the team with a solid performance. He did not quite break into the starting lineup, but Coach Johnson expressed his confidence in Jerry by using him in tight situations. Jerry felt happy to be contributing to the team.

An experiment differs from a study in that the investigator manipulates the variables along with observing them and then examines how changes in one variable affect changes in others. Runners might be divided into two equal groups. One, called the experimental group, would receive training in how to set goals and use imagery and positive self-talk. The other, called the control group, would not receive any psychological skills training. Then, if the experimental group outperformed the control group (with other factors that might affect the relation being controlled), the reason, or cause, for this would be known. A causal relation would have been demonstrated.

Any method of obtaining knowledge has strengths and limitations. The scientific method is no different in this regard. The major strength of scientifically derived knowledge is that it is reliable; that is, scientific findings are consistent or repeatable. Not only is the methodology systematic and controlled, but also the scientists are trained to be as objective as possible. One of their goals is to collect unbiased data—data or facts that speak for themselves and are not influenced by the scientist’s personal feelings.

On the negative side, the scientific method is slow and conservative because reliability must be judged by others. It also takes time to be systematic and controlled—more time than most practitioners have. A breakthrough in science usually comes after years of research. For this reason, it’s not always practical to insist that science guide all elements of practice.

Sometimes scientific knowledge is reductionistic.That is, because it is too complex to study all the variables of a situation simultaneously, the researcher may select isolated variables that are of the most critical interest. When a problem is reduced to smaller, manageable parts, however, our understanding of the whole picture may be compromised or diminished.

Another limitation of science is its overemphasis on internal validity. That is, science favors the extent to which results of an investigation can be attributed to the treatment used, usually judging a study by how well scientists conform to the rules of scientific methodology and how systematic and controlled they were in conducting the study. Too much emphasis on internal validity can cause scientists to overlook external validity, or whether the issue has true significance or utility in the real world. If a theory has no external validity, its internal validity doesn’t count for much. Finally, scientific knowledge tends to be conservative.

Professional Practice Knowledge

Professional practice knowledge refers to knowledge gained through experience. Perhaps, for example, you spend a lot of time helping exercisers, athletes, and physical education students enhance their performance and well-being, and in the process you pick up a good deal of practical understanding or information. Professional practice knowledge comes from many sources and ways of knowing, including these:

Although exercise leaders, coaches, and certified athletic trainers ordinarily do not use the scientific method, they do use theoretically derived sport and exercise principles to guide their practice.

For example, volleyball coach Theresa Hebert works with the high school team. She develops her coaching skills in a variety of ways. Before the season begins, she reflects (uses introspection) on how she wants to coach this year. During team tryouts she uses systematic observation of the new players as they serve, hit, and scrimmage. Last season, she remembers, the team captain—a star setter—struggled, so Coach Hebert wants to learn as much about her as possible to help her more this year. To do this, the coach talks with other players, teachers, and the setter’s parents. In essence, the coach conducts a case study. When she and her assistant coaches compare notes on their scouting of the next opponent, shared public experience occurs. Coach Hebert often uses intuition also—for example, she decides to start Sarah over Rhonda today, the two players having similar ability, because it feels right to her. Of course, these methods are not equally reliable; however, in combination they lead to effective coaching. Like her players, Coach Hebert sometimes makes mistakes. But these errors or miscalculations also become sources of information to her.

Professional practice knowledge is guided trial-and-error learning. Whether you become a physical therapist, coach, teacher, exercise leader, or certified athletic trainer, you will use your knowledge to develop strategies and then to evaluate their effectiveness. With experience, an exercise and sport science professional becomes more proficient and more knowledgeable in practical ways.

Professional practice knowledge also has major strengths and limitations. This practical knowledge is usually more holistic than scientifically derived knowledge, reflecting the complex interplay of many factors—psychological, physical, technical, strategic, and social. And unlike science, professional practice knowledge tends to absorb novel or innovative practices.

Coaches, teachers, exercise leaders, and trainers enjoy using new techniques. Another plus is that practical theories do not have to wait to be scientifically verified, so they can be used immediately.

On the downside, professional practice can produce fewer and less precise explanations than science can. Professional practice is more affected by bias than is science and thus less objective. Practical knowledge tends to be less reliable and definitive than scientifically based knowledge. Often a teacher knows a method works but does not know why. This can be a problem if the teacher wants to use the method in a new situation or revise it to help a particular student.

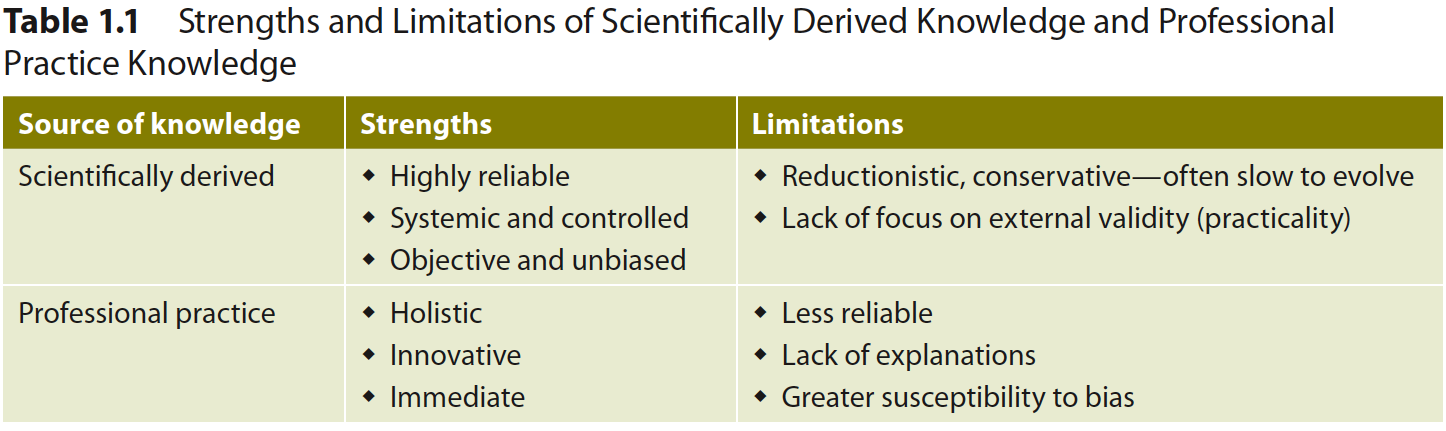

Table 1.1 summarizes the strengths and limitations of both types of knowledge.

Integration of Scientific and Professional Practice Knowledge

The gap you may sense between reading a textbook and pursuing professional activities is part of a larger division between scientific and professional practice knowledge. Yet bridging this gap is paramount, because the combination of the two kinds of knowledge is what makes for effective applied practice.

There are several causes for this gap (Gowan, Botterill, & Blimkie, 1979). Until recently, few opportunities existed to transfer results of research to professionals working in the field: physical educators, coaches, exercise leaders, athletes, exercisers, and trainers. Second, some sport and exercise psychologists were overly optimistic about using research to revolutionize the practice of teaching sport and physical activity skills. Although basic laboratory research was conducted in the 1960s and 1970s, little connection was then made to actual field situations (external validity). The gap must be closed, however, and practitioners and researchers must communicate to integrate their worlds.

Taking an Active Approach to Sport

and Exercise Psychology

To effectively use sport and exercise psychology in the field requires actively developing knowledge. The practitioner must blend the scientific knowledge of sport and exercise psychology with professional practice knowledge. Reading a book like this, taking a course in sport and exercise psychology, or working (as a teacher, coach, or exercise leader) is simply not enough. You must actively integrate scientific knowledge with your professional experiences and temper these with your own insights and

intuition.

To take an active approach means applying the scientific principles identified in subsequent chapters of this book to your practice environments. Relate these principles to your own experiences as an athlete, exerciser, and physical education student. In essence, use the gym, the pool, or the athletic field as a mini-experimental situation in which you test your sport and exercise psychology thoughts and understanding of principles. Evaluate how effective these ideas are and in what situations they seem to work the best. Modify and update them when needed by keeping current regarding the latest sport and exercise psychology scientific findings.

In using this active approach, however, you must have realistic expectations of sport and exercise psychology research findings. Most research findings are judged to be significant based on probability. Hence, these findings won’t hold true 100% of the time. They should work or accurately explain behavior the majority of the time. When they do not seem to predict behavior adequately, analyze the situation to identify possible explanations for why the principle does or does not work and, if the findings are theoretically based, consider the key components of the theory behind the original predictions. See if you need to consider overriding personal or situational factors at work in your practice environment.

Recognizing Sport and Exercise Psychology As an Art

Psychology is a social science. It is different from physics: Whereas inanimate objects do not change much over time, human beings do. Humans involved in sports and exercise also think and manipulate their environment, which makes behavior more difficult (but not impossible) to predict. Coach “Doc” Counsilman (Kimiecik & Gould, 1987), legendary Olympic swim coach and key proponent of a scientific approach to coaching, best summed up the need to consider individuality when he indicated that coaches coach by using general principles, the science of coaching. The art of coaching enters as they recognize when and in what situations to individualize these general principles. This same science-to-practice guiding principle holds true in sport and exercise psychology. Interestingly, some investigators (Brown, Gould, & Foster, 2005) have begun to study contextual intelligence (the ability of individuals to understand and read the contexts in which they work) and its development, which has implications for better understanding how we learn the art of professional practice.

Choosing From Many Sport and Exercise Psychology Orientations

Some coaches believe that teams win games through outstanding defense; other coaches believe teams win through a wide-open offensive system; and still others believe that wins come through a structured and controlled game plan. Like coaches, sport psychologists differ in how they view successful interventions. Contemporary sport and exercise psychologists may choose from many different orientations to the field, three of the most prevalent being psychophysiological, social–psychological, and cognitive–behavioral approaches.

Psychophysiological Orientation

Sport and exercise psychologists with a psychophysiological orientation believe that the best way to study behavior during sport and exercise is to examine the physiological processes of the brain and their influences on the physical activity. These psychologists typically assess heart rate, brain wave activity, and muscle action potentials, determining relationships between these psychophysiological measures and sport and exercise behavior. An example is using biofeedback techniques to train elite marksmen to fire between heartbeats to improve accuracy (Landers, 1985). Hatfield and Hillman (2001) provided a comprehensive review of the research in the area.

Social–Psychological Orientation

Using a social–psychological orientation, sport and exercise psychologists assume that behavior is determined by a complex interaction between the environment (especially the social environment) and the personal makeup of the athlete or exerciser. Those taking the social–psychological approach often examine how an individual’s social environment influences her behavior and how the behavior influences the social–psychological environment. For example, sport psychologists with a social–psychological orientation might examine how a leader’s style and strategies foster group cohesion and influence participation in an exercise program (Carron & Spink, 1993).

Cognitive–Behavioral Orientation

Psychologists adopting a cognitive–behavioral orientation emphasize the athlete’s or exerciser’s cognitions or thoughts and behaviors, believing thought to be central in determining behavior. Cognitive–behavioral sport psychologists might, for instance, develop self-report measures to assess self-confidence, anxiety, goal orientations, imagery, and intrinsic motivation. The psychologists then would see how these assessments are linked to changes in an athlete’s or an exerciser’s behavior. For example, groups of junior tennis players who were either burned out or not burned out were surveyed using a battery of psychological assessments. Burned-out tennis players, compared with non-burned-out players, were found to have less motivation. They also reported being more withdrawn, had more perfectionist personality tendencies, and used different coping strategies for stress (Gould, Tuffey, Udry, & Loehr, 1996a). Thus, links between the athletes’ thoughts and behaviors and the athletes’ burnout status were examined.

Understanding Present and Future Trends

Now that you have learned about the field of sport and exercise psychology, including its history, scientific base, and orientations, you need to understand the significant current and future trends in the area. We briefly discuss 10 trends.

1. More people are interested in acquiring training in psychological skills and applied work. Consulting and service opportunities are more plentiful than ever, and more sport psychologists are helping athletes and coaches achieve their goals. Exercise psychology has opened new service opportunities for helping people enjoy the benefits of exercise. For these reasons, applied sport and exercise psychology will continue to grow into the years to come (Cox, Qui, & Liu, 1993; Murphy, 2005).

2. There is greater emphasis on counseling and clinical training for sport psychologists. Accompanying the increased emphasis on consulting is a need for more training in counseling and clinical psychology (McCullagh & Noble, 1996). Those individuals who want to assume a role in sport and exercise consulting will have to understand not only sport and exercise science but aspects of counseling and clinical psychology as well. Graduate programs are being developed in counseling and clinical psychology, with an emphasis in sport and exercise psychology.

3. Ethics and competence issues are receiving greater emphasis. Some problems have accompanied the tremendous growth in sport and exercise consulting (Murphy, 1995; Silva, 2001). For example, unqualified people might call themselves sport psychologists, and unethical individuals might promise more to coaches, athletes, and exercise professionals than they can deliver. That is, someone with no training in the area might claim to be a sport psychologist and promise that buying his imagery tape will make an 80% free-throw shooter out of a 20% shooter. This is why AASP has begun a certification program for sport and exercise psychology consultants. Ethical standards for sport psychology specialists have also been developed (see “Ethical Standards for Sport and Exercise Psychologists”). Physical education, sport, and exercise leaders should become informed consumers who can discriminate between legitimate, useful information and fads or gimmicks. They must also be familiar with ethical standards in the area.

Ethical Standards for Sport and Exercise Psychologists

Sport psychology is a young profession, and only recently have its organizations—such as the Association for Applied Sport Psychology, and the Canadian Society for Psychomotor Learning and Sport Psychology—developed ethical guidelines. These guidelines are based on the more general American Psychological Association’s ethical standards (2002), and at their core is the general philosophy that sport psychology consultants should respect the dignity and worth of individuals and honor the preservation and protection of fundamental human rights. The essence of this philosophy is that the athlete’s or exerciser’s welfare must be foremost in one’s mind.

The AASP ethical guidelines outline six areas (general principles):

1. Competence. Sport psychologists strive to maintain the highest standards of competence in their work and recognize their limits of expertise. If a sport psychologist has little knowledge of team building and group dynamics, for example, it would be unethical to lead others to believe that he does have this knowledge or to work with a team.

2. Integrity. Sport and exercise psychologists demonstrate high integrity in science, teaching, and consulting. They do not falsely advertise, and they clarify their roles (e.g., inform athletes that they will be involved in team selection) with teams and organizations.

3. Professional and scientific responsibility. Sport and exercise psychologists always place the best interests of their clients first. For instance, it would be unethical to study aggression in sport by purposefully instructing one group of subjects to start fights with the opposing team (even if much could be learned from doing so). Those conducting research are also responsible for safeguarding the public from unethical professionals. If a sport psychologist witnesses another professional making false claims (e.g., that someone can eat all she wants and burn off all the extra fat via imagery), the sport psychologist is ethically bound to point out the misinformation and to professionally confront the offender or report him to a professional organization.

4. Respect for people’s rights and dignity. Sport psychologists respect the fundamental rights (e.g., privacy and confidentiality) of the people with whom they work. They do not publicly identify persons they consult with unless they have permission to do so. They show no bias on the basis of such factors as race, gender, and socioeconomic status.

5. Concern for welfare of others. Sport psychologists seek to contribute to the welfare of those with whom they work. Hence, an athlete’s psychological and physical well-being always comes before winning.

6. Social responsibility. Sport and exercise psychologists contribute to knowledge and human welfare while always protecting participants’ interests. An exercise psychologist, for instance, would not offer an exercise program designed to reduce depression to one group of experimental participants without making the same program available to control group subjects at the end of the experiment. Offering the treatment only to the experimental group would not be socially responsible and, indeed, would be unethical.

4. Specializations and new subspecialties are developing. In the past 30 years, knowledge in sport psychology has exploded. Unlike their forerunners, today’s sport psychologists cannot be experts in every area that you will read about in this text. This has led to the separation of sport psychology as defined here and motor learning or motor control (the acquisition and control of skilled movements as a result of practice) as separate sport science areas. In addition, subspecializations within sport and exercise psychology are emerging (Rejeski & Brawley, 1988; Singer, 1996). Exercise psychology is the most visible growth area. However, other new specializations that are attracting considerable interest include youth life skills development through sport (see chapter 11) and the psychology of performance excellence (applying sport psychology performance enhancement principles to other settings such as music, arts, and business [see Hays, 2009]). We expect this trend toward specialization to continue.

5. Tension continues to exist between practitioners of academic and applied sport psychology. This textbook is based on the philosophy that sport psychology will best develop with an equal emphasis on research and professional practice; however, not all sport psychologists hold this view. Some tension has developed between academic (research) and applied sport psychology consultants, each group believing that the other’s activities are less crucial to the development of the field. Although such tension is certainly undesirable, it is not unique. Similar disagreement, for example, exists in the broader field of psychology. Sport psychologists must continue working to overcome this destructive thinking.

6. Qualitative research methods are receiving more attention. The 1990s reflected a change in the way sport and exercise psychologists conduct research. Although traditional quantitative research is still being conducted, many investigators are broadening the way they do research by using qualitative (nonnumeric) methods. Such methods entail collecting data via observation or interviews; instead of analyzing numbers or ratings statistically, researchers analyze the respondents’ words and stories or narration for trends and patterns. This has been a healthy development for the field.

7. Applied sport psychologists have more work opportunities than ever but only limited chances at full-time positions. On the one hand, they have more opportunities to work with teams and consult with athletes. Many consultants now work part-time with elite amateur athletes through various national sport governing bodies (NGBs) such as the U.S. Tennis Association and U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association. Some NGBs, the U.S. Olympic Committee, and several universities have full-time sport psychology consultants to serve varsity athletes, and many professional teams employ a sport psychologist. On the other hand, however, few full-time consulting positions exist. Furthermore, a person needs advanced graduate training to become a qualified sport psychology specialist. Hence, people should not expect to quickly obtain full-time consulting positions with high-profile teams and athletes simply on the basis of a degree in sport psychology.

Sport Psychology–Business Link

A number of sport psychology specialists have been transferring what they learned in sport to the world of business. Here are two examples:

8. Sport and exercise psychology has become a recognized sport science of considerable utility and is receiving increased attention and recognition all around the world. Many universities now offer sport and exercise psychology courses, and some graduate programs include up to five or six different courses. Research and professional resources are increasingly available to students. However, we believe that the greatest gains are still to come. Physical education teachers, coaches, fitness instructors, and certified athletic trainers have increasing access to information about sport and exercise psychology. With this up-to-date information, physical activity professionals will make great strides toward achieving their various goals. In short, the field of sport and exercise psychology has much to offer you, the physical education teachers, coaches, fitness specialists, and certified athletic trainers of the future.

9. In the general field of psychology, a positive.psychology movement has been embraced by a number of leaders in the field (e.g., Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002). This movement emphasizes the need for psychologists to focus more on the development of positive attributes such as optimism, hope, and happiness in individuals, as opposed to focusing the majority of attention on people’s deficits (e.g., depression). Sport and exercise psychologists have been practicing positive performance for some time, which has opened up new opportunities. For example, leading sport psychologists such as Graham Jones, Jim Loehr, Austin Swain, Shane Murphy, and Steve Bull have taken what they learned in sport to the business world, teaching business people how to enhance their psychological skills and work performance. Similarly, sport psychologist Kate Hays (Hays, 2002; 2009) has helped elite performance artists such as dancers and musicians develop psychological skills, needed for top performance.

10. The importance of embracing the globalization of sport and exercise psychology is paramount for contemporary students of the field and will increase in years to come. New knowledge and best practices are rapidly being developed in a host of European, Asian, and South American countries. In addition to giving us new knowledge developed in other parts of the world, examining sport psychology across cultures allows us to understand which principles generalize across cultures and which are culturally bound. To understand contemporary sport and exercise psychology, a global perspective is essential and will only grow in importance.

Learning Aids

Summary

1. Describe what sport and exercise psychology is.

Sport and exercise psychology is the scientific study of the behavior of people engaged in sport and exercise activities and the application of the knowledge gained. Researchers in the field have two major objectives: (a) to understand how psychological factors affect a person’s motor performance and (b) to understand how participating in physical activity affects a person’s psychological development. Despite enormous growth in recent years, sport psychology dates back to the early 1900s and is best understood within the framework of its six distinct historical periods.

2. Understand what sport and exercise psychology specialists do.

Contemporary sport and exercise psychologists engage in different roles, including conducting research, teaching, and consulting with athletes and exercisers.

3. Know what training is required of a sport and exercise psychologist.

Not all sport and exercise psychology specialists are trained in the same way. Clinical sport and exercise psychologists are trained specifically in psychology to treat athletes and exercisers with severe emotional disorders, such as substance abuse or anorexia. Educational sport psychology specialists receive training in exercise and sport science and related fields; they serve as mental coaches, educating athletes and exercisers about psychological skills and their development. They are not trained to assist people with severe emotional disorders.

4. Understand major developments in the history of sport and exercise psychology.

Sport and exercise psychology has a long and rich history dating back more than 100 years. Its history falls into six periods. The first period, the early years (1893–1920), was characterized by isolated studies. During the Griffith era (1921–1938), Coleman Griffith became the first American to specialize in the area. The third period, preparation for the future (1939–1965), was characterized by the field’s scientific development attributable to the educational efforts of Franklin Henry. During the establishment of the academic discipline (1966–1977), sport and exercise psychology became a valued component of the academic discipline of physical education. The fifth period, multidisciplinary science and practice (1978–2000), was characterized by tremendous growth as the field became more accepted and respected by the public. Interest in applied issues and the growth and development of exercise psychology were evident. Training in the field took a more multidisciplinary perspective, and the field wrestled with a variety of professional practice issues. The final period of contemporary sport and exercise psychology (2001–present) has been distinguished by continued growth worldwide, considerable diverse research, and interest in application and consulting. Exercise psychology flourishes.

5. Distinguish between scientific and professional practice knowledge.

Sport and exercise psychology is above all a science. For this reason you need to understand the basic scientific process and how scientific knowledge is developed. Scientific knowledge alone, however, is not enough to guide professional practice. You must also understand how professional practice knowledge develops.

6. Integrate experiential and scientific knowledge.

Scientific knowledge must be integrated with the knowledge gained from professional practice. Integrating scientific and professional practice knowledge will greatly benefit you as you work in applied sport and exercise settings.

7. Compare and contrast orientations to the field.

Several approaches can be taken to sport and exercise psychology, including the psychophysiological, social–psychological, and cognitive–behavioral orientations. Psychophysiological sport psychologists study physiological processes of the brain and their influence on physical activity. Social–psychological sport psychologists focus on how complex interactions between the social environment and personal makeup of the athlete or exerciser influence behavior. Cognitive–behavioral sport psychologists examine how an individual’s thoughts determine behavior.

8. Describe career opportunities and future directions in the field.

Although there are more career opportunities today than ever before, only limited numbers of full-time consulting positions are available. Sport and exercise psychology is flourishing and has much to offer those interested in working in sport and physical activity settings. Trends point to such future directions as an increased interest in psychological skills training and applied work, more counseling and clinical training for sport psychologists, increased emphasis on ethics and competence, increased specialization, some continuing tension between academic and applied sport psychologists, more qualitative research, and the need to take a global perspective.

Key Terms

sport and exercise psychology

clinical sport psychologists

educational sport psychology specialists

scientific method

systematic approach

control

empirical

critical

theory

social facilitation theory

study

experiment

experimental group

control group

unbiased data

reductionistic

internal validity

external validity

professional practice knowledge

introspection

systematic observation

case study

shared public experience

intuition

psychophysiological orientation

social–psychological orientation

cognitive–behavioral orientation

Review Questions

1. What is sport and exercise psychology, and what are its two general objectives?

2. Describe the major accomplishments of the six periods in the history of sport and exercise psychology. What contributions did Coleman Griffith and Franklin Henry make to sport and exercise psychology?

3. Describe three roles of sport and exercise psychology specialists.

4. Distinguish between clinical and educational sport psychology. Why is this distinction important?

5. Define science and explain four of its major goals.

6. What is a theory and why are theories important in sport and exercise psychology?

7. Distinguish between a research study and an experiment.

8. Identify the strengths and limitations of scientifically derived knowledge and professional practice knowledge. How does each develop?

9. Describe the gap between research and practice, why it exists, and how it can be bridged.

10. Briefly describe the psychophysiological, social–psychological, and cognitive–behavioral orientations to the study of sport and exercise psychology.

11. Why is there a need for certification in contemporary sport and exercise psychology?

12. Identify and briefly describe the six major ethical principles in sport and exercise psychology.

13. What career opportunities exist in sport and exercise psychology?

14. Why do contemporary sport psychologists need to take a global perspective?

Critical Thinking Questions

1. Describe the active approach to using sport and exercise psychology.

2. You are interested in investigating how self-confidence is related to athletic injury recovery. Design both a study and an experiment to do so.

3. Think of the career you would like to pursue (e.g., sport and exercise psychology, coaching, certified athletic training, sport journalism). Describe how the knowledge and the practice of sport psychology can affect you in that career.