After reading this chapter, you should be able to

1. explain how positive feedback and negative feedback influence behavior,

2. understand how to implement behavior modification programs,

3. discuss the different types of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation,

4. describe the relationship between intrinsic motivation and external rewards (controlling and informational aspects),

5. detail different ways to increase intrinsic motivation,

6. describe how such factors as scholarships, coaching behaviors, competition, and feedback influence intrinsic motivation, and

7. describe the flow state and how to achieve it.

People thirst for feedback. An exerciser feels like a klutz and hopes for a pat on the back, some telling instruction, and a camera to capture the moment she finally gets the steps right. Similarly, a youngster trying to learn how to hit a baseball after a series of missed swings feels great when he finally connects with the next pitch. To create an environment that fosters pleasure, growth, and mastery, professionals use motivational techniques based on the principles of reinforcement. Reinforcement is the use of rewards and punishments that increase or decrease the likelihood of a similar response occurring in the future. The principles of reinforcement are among the most widely researched and accepted in psychology. They are firmly rooted in the theories of behavior modification and operant conditioning. The late B.F. Skinner, the most widely known and outspoken behavior theorist, argued that teaching rests entirely on the principles of reinforce-

ment.

For example, Skinner (1968) argued that teaching is the arrangement of reinforcers under which students learn. “Students learn without teaching in their natural environment, but teachers arrange special reinforcements that expedite learning, hastening the appearance of behavior that would otherwise be acquired slowly or making sure of the appearance of behavior that might otherwise never occur” (pp. 64–65). Providing students, athletes, and exercisers with constructive feedback requires an understanding of the principles of reinforcement.

Principles of Reinforcement

Although there are many principles related to changing behavior, two basic premises underlie effective reinforcement: First, if doing something results in a good consequence (such as being rewarded), people will tend to try to repeat the behavior to receive additional positive consequences; second, if doing something results in an unpleasant consequence (such as being punished), people will tend to try not to repeat the behavior so they can avoid more negative consequences.

Imagine a physical education class on soccer skills in which a player makes a pass to a teammate that leads to a goal. The teacher says, “Way to pass the ball to the open man—keep up the good work!” The player will probably try to repeat that type of pass in the future to receive more praise from the coach. Now imagine a volleyball player going for a risky jump serve and hitting the ball into the net. The coach yells, “Use your head—stop trying low-percentage serves!” Most likely, this player will not try this type of serve again, wanting to avoid the criticism from the coach.

Reinforcement principles are more complex than you might think, however, in the real world. Often the same reinforcer will affect two people differently. For example, a reprimand in an exercise class might make one person feel she is being punished, whereas it might provide attention and recognition for another person. A second difficulty is that people cannot always repeat the reinforced behavior. For instance, a point guard in basketball scores 30 points, although his normal scoring average is 10 points a game. He receives praise and recognition from the fans and the media for his high scoring output and naturally wants to repeat this behavior. However, he is a much better passer than a shooter: When he tries hard to score more points, he actually hurts his team and lowers his shooting percentage because he attempts more low-percentage shots. You must also consider all the reinforcements available to the individual, as well as how she values them. For example, someone in an exercise program receives great positive reinforcement from staying in shape and looking good. But because of her participation in the program she spends less time with her spouse, which is an aversive consequence that outweighs the positive reinforcer, so she drops out of the program. Unfortunately, coaches, teachers, and exercise leaders are often unaware of these competing motives and reinforcers.

Approaches to Influencing Behavior

There are positive and negative ways to teach and coach. The positive approach focuses on rewarding appropriate behavior (e.g., catching people doing something correctly), which increases the likelihood of desirable responses occurring in the future. Conversely, the negative approach focuses on punishing undesirable behaviors, which should reduce the inappropriate behaviors. The positive approach is designed to strengthen desired behaviors by motivating participants to perform those behaviors and by rewarding participants when those behaviors occur. The negative approach, however, focuses on errors and thus attempts to eliminate unwanted behaviors through punishment and criticism. For example, if an exerciser was late for class, the exercise leader might criticize the person with the hope of producing more on-time behavior in the

future.

Most coaches combine the positive and negative approaches in attempting to motivate and teach their athletes. However, sport psychologists agree that the predominant approach with sport and physical activity participants should be positive (Smith, 2006). We see this in a quote by Louisville basketball coach, Rick Pitino: “You can program yourself to be positive. Being positive is a discipline…. And the more adversity you face the more positive you have to be. Being positive helps build confidence and self-esteem which is critical to succeeding” (Pitino 1998, pp. 78–80). Phil Jackson, eleven-time NBA championship coach, uses a 2 to 1 ratio of positive to negative feedback, although the Positive Coaching Alliance, which trains youth sport coaches, recommends a 5 to 1 ratio. Jackson argues that at the professional level, it is hard to come up with five positives for every negative, but he does understand that players won’t listen to you or react positively if you simply attack them with criticism. He firmly believes that any message will be more effective if you pump up players’ egos before you bruise their egos (Jackson, 2004).

Guidelines for Using Positive Reinforcement

Sport psychologists highly recommend a positive approach to motivation to avoid the potential negative side effects of using punishment as the primary approach. Research demonstrates that athletes who play for positive-oriented coaches like their teammates better, enjoy their athletic experience more, like their coaches more, and experience greater team cohesion (Smith & Smoll, 1997). The following quote by Jimmy Johnson, former coach of the Miami Dolphins and Dallas Cowboys, sums up his emphasis on the positive: “I try never to plant a negative seed. I try to make every comment a positive comment. There’s a lot of evidence to support positive management” (cited in Smith, 2006, p. 40). Reinforcement can take many forms including verbal compliments, smiles or other nonverbal behaviors that imply approval, increased privileges, and the use of rewards (just to name a few). So let’s examine some of the principles underlying the effective use of positive reinforcement.

Choose Effective Reinforcers

Rewards should meet the needs of those receiving them. It is best to know the likes and dislikes of the people you work with and choose reinforcers accordingly:

A physical education teacher might have students complete a questionnaire to determine what type of rewards they most desire (e.g., social, material, activity). This information could help a teacher pinpoint the type of reinforcer to use for each student. Similarly, athletic trainers might develop a list of the types of reinforcements athletes react most favorably to when recovering from difficult injuries. Sometimes you might want to reward the entire team or class, rather than a particular individual, or vary the types of rewards (it can become monotonous to receive the same reinforcement repeatedly).

The kinds of rewards that people receive from others are called extrinsic because they come from external sources (outside the individual), such as the coach or the teacher. Other rewards are called intrinsic because they reside within the participant. Examples of intrinsic rewards are taking pride in accomplishment and feeling competent. Although coaches,teachers, and exercise leaders cannot directly offer intrinsic rewards, they can structure the environment to promote intrinsic motivation. For example, it has been demonstrated that if an environment is more focused on learning, effort, and improvement as opposed to competition, outcome, and social comparison, then participants tend to be more intrinsically motivated (see “Creating a Positive Motivational Climate” on page 128). We further discuss the relationship between extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation later in this chapter.

Creating a Positive Motivational Climate

Research originally conducted in schools (Epstein, 1989) and then applied to sport and physical education (Treasure & Roberts, 1995) has argued that a mastery-oriented climate can foster intrinsic motivation and self-confidence. The acronym TARGET was developed to represent the manipulation of environmental conditions that foster a mastery-oriented environment.

1. Tasks. Focus on learning and task involvement (play down competitive and social comparison aspects and focus on simply learning new skills).

2. Authority. Allow students to participate in the decision-making process (e.g., ask athletes for input on new drills).

3. Reward. Reward for improvement, not social comparison (e.g., reward when athletes improve the number of push-ups they can do regardless of how they rate against others).

4. Grouping. Create cooperative learning climates within groups (have athletes work together to solve problems rather than compete against each other).

5. Evaluation. Have numerous evaluations focusing on personal improvement (evaluate progress and learning, not just who is the best at a given task).

6. Timing. Use proper timing for all of these conditions (provide feedback as immediately as possible after the athlete performs the task).

More recently, research in sport has focused on coach-created motivational climate (Duda & Balague, 2007), parent-created motivational climate (White, 2007), and peer-created motivational climate (Ntoumanis, Vazou, & Duda, 2007). Although in all three cases the focus is on creating more of a mastery-oriented environment (such as the TARGET program just noted), the details are specific to each group forming the motivational climate. But all three approaches focus on creating a motivational climate that fosters equal treatment, cooperation, autonomy, mastery of skills, social support, and effort.

Schedule Reinforcements Effectively

Appropriate timing and frequency can ensure that rewards are effective. During the initial stages of training or skill development, desirable responses should be reinforced often, perhaps on an almost continuous schedule. A continuous schedule requires rewarding after every correct response, whereas on a partial schedule, behavior is rewarded intermittently.

Research has indicated that continuous feedback not only acts as a motivator but also provides the learner with information about how he is doing. However, once a particular skill or behavior has been mastered or is occurring at the desired frequency, the schedule can be gradually reduced to intermittent (Martin & Pear, 2003). To underscore the effects of continuous and intermittent reinforcement, it is important to understand the difference between learning and performance. Research (Schmidt & Wrisberg, 2004) has revealed that giving feedback after every attempt (continuous—100%) is far better for performance during practice than giving it after every other attempt (intermittent—50%). But on tests of retention given the next day without any feedback, participants with only 50% feedback performed better than those given 100% feedback. In essence, feedback after every trial was used as a kind of “crutch,” so that the learner was unable to perform effectively when the “crutch” was removed. Besides reducing the amount of feedback given, coaches might ask athletes to generate their own feedback. For example, after a tennis player hits a couple of balls into the net, a coach might ask him, “Why do you think the ball went into the net?” This forces players to evaluate their own internal feedback, as well as the outcome, instead of relying too heavily on coach feedback.

The sooner after a response a reinforcement is provided, the more powerful the effects on behavior. This is especially true when people are learning new skills, when it is easy to lose confidence if the skill isn’t performed correctly. Once someone masters a skill, it is less critical to reinforce immediately, although it is still essential that the correct behaviors be reinforced at some point.

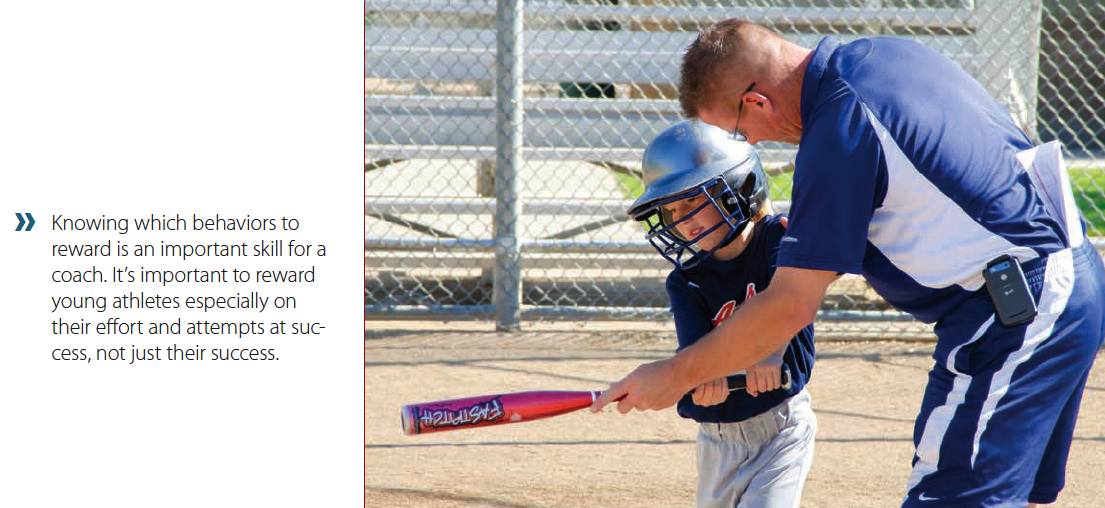

Reward Appropriate Behaviors

Choosing the proper behaviors to reward is also critical. Obviously you cannot reward people every time they do something right. You have to decide on the most appropriate and important behaviors and concentrate on rewarding these. Many coaches and teachers tend to focus their rewards purely on the outcome of performance (e.g., winning), but other behaviors could and should be reinforced, which we will now discuss.

Reward Successful Approximations

When individuals are acquiring a new skill, especially a complex one, they inevitably make mistakes. It may take days or weeks to master the skill, which can be disappointing and frustrating for the learner. It is helpful, therefore, to reward small improvements as the skill is learned. This technique, called shaping, allows people to continue to improve as they get closer and closer to the desired response (Martin & Hrycaiko, 1983). Specifically, individuals are rewarded for performances that approximate the desired performance.

This spurs their motivation and provides direction for what they should do next. For example, if players are learning the overhand volleyball serve, you might first reward the proper toss, then the proper motion, then good contact, and finally the execution that puts all the parts together successfully. Similarly, an aerobics instructor might reward participants for learning part of a routine until they have mastered the entire program. Or a physical therapist might reward a client for improving the range of motion in her shoulder (after surgery) through adhering to her stretching program, even though she still has room for improvement.

Reward Performance, Not Only Outcome

Coaches who emphasize winning tend to reward players based on outcome. A baseball player hits a hard line drive down the third base line, but the third baseman makes a spectacular diving catch. In his next at bat, the same batter tries to check his swing and hits the ball off the end of the bat, just over the outstretched arm of the second baseman, for a base hit. Rewarding the base hit but not the out would be sending the wrong message to the player. If an individual performs the skill correctly, that’s all he can do. The outcome is sometimes out of the player’s control, so the coach should focus on the athlete’s performance instead of the performance outcome.

It is especially important to use an individual’s own previous level of performance as the standard for success. For example, if a young gymnast’s best score on her floor routine was 7.5 and she received a 7.8 for her most recent effort, then this mark should be used as the measure of success and she should be rewarded for her performance.

Reward Effort

Coaches and teachers must recognize effort as part of performance. Not everyone can be successful in sport. When sport and exercise participants (especially youngsters) know that they will be recognized for trying new and difficult skills, and not just criticized for performing incorrectly, they do not fear trying. All they can do is try as hard as possible, and if this is recognized, then they have nothing to fear. Former UCLA basketball coach John Wooden encapsulated this concept of focusing on effort instead of winning:

You cannot find a player who ever played for me at UCLA that can tell you he ever heard me mention winning a basketball game. He might say I inferred a little here and there, but I never mentioned winning. Yet the last thing that I told my players, just prior to tip-off, before we would go out on the floor was, when the game is over, I want your head up—and I know of only one way for your head to be up—and that’s for you to know you did your best…. This means to do the best you can do. That’s the best; no one can do more…. You made that effort.

Interestingly, a study conducted with youth (Mueller & Dweck, 1998) showed that performers who received effort-oriented feedback (“Good try”) would display better performance than those provided ability-oriented feedback (“You’re talented”), especially after failure. Specifically, after failure, children who were praised for effort displayed more task persistence, more task enjoyment, and better performance than children praised for high ability. Thus, effort (which is under one’s control) appears to be critical to producing persistence, which is one of the most highly valued attributes in sport and exercise environments.

Reward Emotional and Social Skills

With the pressure to win, it is easy to forget the importance of fair play and being a good sport. Athletes who demonstrate good sporting behavior, responsibility, judgment, and other signs of self-control and cooperation should be recognized and reinforced. Unfortunately, some high-visibility athletes and coaches have not been good role models and have been accused or convicted of such acts as physical or verbal abuse of officials and coaches, substance abuse, physical or sexual abuse, and murder. One of the reasons that basketball administrators were so dismayed over the 2005 fight between the Detroit Pistons and Indiana Pacers and the fans (which resulted in significant suspensions of several players) was the message it sent to youngsters. Displaying restraint despite being “egged on” by fans is an important social skill that athletes need to learn, because it relates to many life situations. As leaders of sport and physical activity, we have a tremendous opportunity and responsibility to encourage positive emotional and social skills. We should not overlook the chance to reward such positive behaviors, especially in younger participants.

Provide Performance Feedback

Help participants by giving them information and feedback about the accuracy and success of their movements. This type of feedback is typically provided after the completion of a response. For example, an athletic trainer working with an injured athlete on increasing his flexibility while rehabilitating from a knee injury asks the athlete to bend his knee as far as possible. The trainer then tells the athlete that he has improved his flexibility from 50º to 55º since the week before. Similarly, a fitness instructor might give participants specific feedback about proper positioning and technique when they are lifting weights.

When you give feedback to athletes, students, and exercisers, the feedback should be sincere and contingent on some behavior. Whether it is praise or criticism, the feedback needs to be tied to (contingent on) a specific behavior or set of behaviors. It would be inappropriate, for example, to tell a student in a physical education class who is having difficulty learning a new gymnastics skill, “Way to go, keep up the good work!” Rather, the feedback should be specific and linked to performance. Inform the athlete how to perform the skill correctly, perhaps saying, “Make sure you keep your chest tucked close to your body during the tumbling maneuver.” Such feedback, when sincere, demonstrates that you care and are concerned with helping the learner.

There has been a surge of interest in performance feedback as a technique for improving performance in business, industry, and sport (Huberman & O’Brien, 1999; Latham & Seijts, 1999; Tauer & Harackiewicz, 1999). The evidence indicates that this type of feedback is effective in enhancing performance. In fact, it was found that performance increased on average by 53% after performance feedback and indicators of performance excellence had been instituted.

Benefits of Feedback

Feedback about performance can benefit participants in several ways, and two of the main functions are to motivate and to instruct. Motivational feedback attempts to facilitate performance by enhancing confidence, inspiring greater effort and energy expenditure, and creating a positive mood. Examples include “Hang in there,” “You can do it,” and “Get tough.” A second way that feedback can be motivating is by serving as a valuable reinforcement to the performer, which would in turn stimulate positive or negative feelings. For example, individuals receiving specific feedback indicating poor performance might become dissatisfied with their current level of performance. This feedback can motivate them to improve, but they should also experience feelings of satisfaction that function as positive feedback when subsequent feedback indicates improvement. A third motivational function of feedback relates to establishing goal-setting programs. Clear, objective knowledge of results is critical to productive goal setting (see chapter 15) because, in essence, effective goals are specific and measurable. Thus, individuals benefit from getting specific feedback to help them set their goals.

Instructional feedback provides information about (a) the specific behaviors that should be performed, (b) the levels of proficiency that should be achieved, and (c) the performer’s current level of proficiency in the desired skills and activities. When skills are highly complex, the instructional component of knowledge of results can be particularly important. Breaking down complex skills into their component parts creates a more effective learning environment and gives the learner specific information on how to perform each phase of the skill.

A recent development in feedback is represented in a technique called the Method of Amplification Error (MAE). Method of Amplification Error is based on the assumption that participants can learn to correct their movements through their mistakes. In essence, participants are asked to amplify their principal error during a given performance. Through this instruction, they achieve a better understanding of what not to do; therefore they are more capable of readjusting the entire motion during subsequent attempts. Studies (e.g., Milanese, Facci, Cesari, & Zancanzro, 2008) have supported the effectiveness of MAE against other instructional techniques.

Types of Feedback

Verbal praise, facial expressions, and pats on the back are easy, effective ways to reinforce desirable behaviors. Phrases such as “Well done!” “Way to go!” “Keep up the good work!” and “That’s a lot better!” can be powerful reinforcers. However, this reward becomes more effective when you identify the specific behaviors you are pleased with. For instance, a track coach might say to a sprinter, “Way to get out of the blocks—you really pushed off strongly with your legs.” Or an aerobics instructor might say to a participant who is working hard, “I like the way you’re pumping your arms while stepping in place.” The coach and the instructor have identified exactly what the participants are doing well.

Guidelines For Using Punishment

Positive reinforcement should be the predominant way to change behavior; in fact, most researchers suggest that 80% to 90% of reinforcement should be positive. Despite this near consensus among sport psychologists about what fosters motivation in athletes, some coaches use punishment as the primary motivator (Smith, 2006). For example, school achievement for athletes is often prompted by a fear of punishment, such as having one’s eligibility taken away because of poor grades. However, Seifried (2008) presents a view of the pros and cons of using punishment based on empirical research. (A reaction to this article is presented by Albrecht, 2009.) A summary of Seifried’s arguments is presented next.

Support of Punishment

Although a number of educators argue against the use of punishment by coaches, others (e.g., Benatar, 1998) argue that due to the closeness of coaches and athletes, punishment can serve a useful educational purpose (i.e., maintain stability, order, mastery). Punishment certainly can control and change negative behavior (Smith, 2006), and it has advocates among coaches and teachers who use punishment to improve learning and performance. A number of other arguments support the use of punishment in athletic settings:

Criticisms of Punishment

Several different arguments have been put forth to suggest that punishment severely lacks any base of support and in fact is related to negative (unproductive) behaviors. These arguments include the following:

Making Punishment Effective

Some coaches assume that punishing athletes for making mistakes will eliminate these errors. These coaches assume that if players fear making mistakes, they will try harder not to make them. However, successful coaches who used punishment usually were also masters of strategy, teaching, or technical analysis. Often those were the attributes—not their negative approach—that made them successful. Although not recommended as the major source of motivation, punishment might be necessary occasionally to eliminate unwanted behaviors. Here are some guidelines for maximizing the effectiveness of punishment (Martens et al., 1981):

Behavior Modification in Sport

Systematic application of the principles of positive and negative reinforcement to help produce desirable behaviors and eliminate undesirable behaviors has been given various names in the sport psychology literature: contingency management (Siedentop, 1980), behavioral coaching (Martin & Lumsden, 1987), and behavior modification (Donahue, Gillis, & King, 1980). These terms all refer to attempts to structure the environment through the systematic use of reinforcement, especially during practice. In general, behavioral techniques are used in sport and physical activity settings to help individuals stay task oriented and motivated throughout a training period. In what follows, we highlight a few studies that have used behavioral techniques in sport settings and then offer some guidelines for designing behavior programs.

Negative Approaches to Motivation: What Not to Do

Unfortunately, many coaches attempt to motivate their athletes predominantly through fear, threats, criticism, and intimidation. Although these methods often are effective in the short term, they typically backfire in the long term. These are some typical (not recommended) ways that coaches have tried taking a negative approach to motivation:

Evaluating Behavioral Programs

The evidence to date suggests that systematic reinforcement techniques can effectively modify various behaviors, including specific performance skills and coaching and teaching behaviors, as well as reduce errors. Behavioral techniques have successfully changed attendance at practice; have increased output by swimmers in practice (Koop & Martin, 1983); have improved fitness activities (Leith & Taylor, 1992) and gymnastics performance (Wolko, Hrycaiko, & Martin, 1993); have reduced errors in tennis, football, and gymnastics (Allison & Ayllon, 1980); and have improved golf performance (Simek, O’Brien, & Figlerski, 1994). Other programs have effectively used behavioral techniques to decrease off-task behaviors by figure skaters (Hume, Martin, Gonzalez, Cracklen, & Genthon, 1985) and to change or develop healthier attitudes toward good sporting behavior and team support (Galvan & Ward, 1998). Let’s look closely at a few examples of successful behavioral

programs.

Feedback and Reinforcement in Football

In a classic study that provides a good first example, Komaki and Barnett (1977) used feedback and praise to improve specific football performance skills. Barnett, who coached a Pop Warner football team, wanted to know if his players were improving in the basic offensive plays. He and Komaki targeted three specific plays (plays A, B, and C) run from the wishbone offense (a formation that requires specific positioning of the running backs and quarterback) and the five players (center, quarterback, and running backs) responsible for their proper execution. For their study they broke each play into five stages. For instance, one play included (1) a quarterback–center exchange, (2) a quarterback–right halfback fake, (3) a fullback blocking the end, (4) a quarterback decision to pitch or keep, and (5) quarterback action.

After collecting data during an initial baseline period (10 practices or games), the coach systematically reinforced and provided feedback for play A, play B, and play C. This feedback included

To test the effectiveness of the behavioral program, the authors compared the percentage of stages performed correctly for each play during the baseline and reinforcement (about 2 weeks) periods. After 2 weeks, correct performances increased on play A from 62% at baseline to 82%, on play B from 54% to 82%, and on play C from 66% to 80%.

Behavioral Coaching in Golf

Another behavioral program targeted the performance of novice golfers (O’Brien & Simek, 1983). This study used a type of behavioral change program known as backward chaining. In this approach, the last step in a chain is first established (e.g., putting the ball into the hole). Then the last step is paired with the next-to-last step (e.g., driving or chipping the ball onto the green), and so forth, with the steps finally progressing back to the beginning of the chain. In the case of golf, the last step in the chain would be putting on the green into the hole. Putting the ball into the hole in the smallest number of strokes is the goal in golf, and the successful putt should therefore be reinforced. As the next step, chipping onto the green is the focus, and putts are made as reinforcement. Then comes the fairway shot, followed by a successful chip and an equally successful putt. The final step involves driving the ball off the tee box, followed in turn by successful completion of the previous three steps.

This behavioral approach using backward chaining was compared with traditional coaching methods used in training novice golfers. Results revealed that golfers receiving the backward chaining instruction scored some 17 strokes lower than golfers in the traditionally coached control group. In essence, the behavioral coaching group scored almost 1 stroke per hole (18 holes) better than the traditional coaching group—an amazing improvement.

Using Feedback During Practice Sessions

Although many coaches provide extensive feedback to their athletes during their practices, unfortunately the types of feedback they provide often do not maximize learning and time on task. Here are some suggestions for providing feedback during practices to maximize its effectiveness.

Recording and Shaping in Basketball

Another behavioral program targeted both performance and nonperformance behaviors (Siedentop, 1980). A junior high school basketball coach was distressed that his players criticized each other so often in practice while failing to concentrate on shooting skills. The coach decided to award points for daily practice in layups, jump shooting, and free-throw drills and for being a team player (which meant that you encouraged your teammates during play and practice). In this system, points were deducted if the coach saw an instance of a “bad attitude.” An “Eagle effort board” was posted in a conspicuous place in the main hall leading to the gymnasium, and outstanding students received an “Eagle effort” award at the postseason banquet.

The program produced some dramatic changes: After just a few weeks, jump shooting improved from 37% to 51%, layups increased from 68% to 80%, and foul shooting improved from 59% to 67%. But the most dramatic improvement was in the team player category. Before implementing the behavioral program, the coach had detected 4 to 6 instances of criticism during each practice session, along with 10 to 12 instances of encouragement among teammates. After only a few sessions, more than 80 encouraging statements were recorded during a practice session. At the end of the season the coach commented, “We were more together than I ever could have imagined.” Another example of a behavioral program to increase attendance and participation in an age-group swimming program is provided on page 136 in “Improving Attendance: A Behavioral Approach.”

Inappropriate Tennis Behaviors

In a more recent study using a case study design (Galvan & Ward, 1998), the aim was to reduce the amount of inappropriate on-court behavior in collegiate tennis players including racket abuse, ball abuse, verbal abuse, and physical abuse (of self). The number of each player’s inappropriate behaviors was posted on the bulletin board in the players’ locker room. To derive these numbers, the investigators observed all challenge matches (competitive matches between teammates) during practice and recorded the inappropriate behaviors. All players were told of their inappropriate behaviors during an initial meeting and baseline period and were provided strategies to reduce these behaviors. All five players who were followed through a competitive tennis season had a significant reduction in inappropriate behaviors, especially the behaviors that they had initially exhibited most frequently. For example, one player had averaged more than 11 verbal abuses per match during the baseline period, and this number decreased to a little more than 2 per match by the end of the season. So, the behavior modification of the posting appeared to work well for this group of collegiate players.

Creating Effective Behavioral Programs

Although the examples demonstrate that behavioral change programs can alter behavior, actually changing behavior in sport and exercise settings can be a tricky proposition. Effective behavioral programs have certain major characteristics:

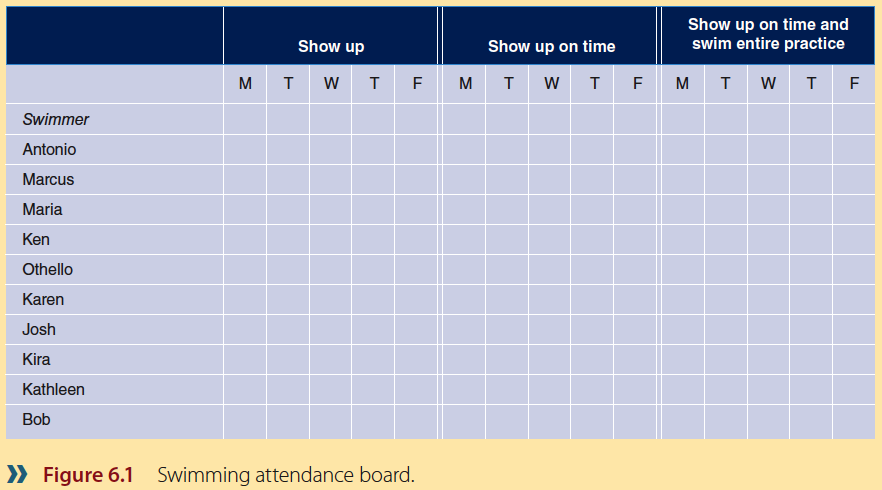

Improving Attendance: A Behavioral Approach

A swimming team was showing poor attendance and punctuality at practices. To solve the problem, the swim coach made an attendance board with each swimmer’s name. She placed the board prominently on a wall by the swimming pool where everyone could see it (see figure 6.1). In the first phase of the program, swimmers who came to practice received a check on the board next to their names. In the second phase, swimmers had to show up on time to receive a check. In the final phase, swimmers had to show up on time and swim for the entire session to receive a check. Results indicated a dramatic increase in attendance at each phase of the study—the increases were 45%, 63%, and 100% for the three phases, respectively (McKenzie & Rushall, 1974). A more recent study (Young, Medic, & Starkes, 2009) found that self-monitoring logs improved attendance and punctuality of intercollegiate swimmers but the effect only lasts about 2-3 weeks. Thus, additional motivation is needed for continued adherence.

Then a public program board was developed on which swimmers could check off each lap of a programmed workout. The group increased its performance output by 27%, equivalent to an additional 619 yards for each swimmer during the practice session! The public nature of the attendance and program boards clearly served a motivational function: Every swimmer could see who was attending, who was late, who swam the entire period, and how many laps each swimmer completed. Coaches and swimmers commented that peer pressure and public recognition helped make the program successful, along with the attention, praise, and approval of coaches after swimmers’ checks were posted on the board.

Clearly, behavioral techniques can produce positive changes in a variety of behaviors. As you apply behavioral techniques, the following guidelines can increase the effectiveness of your intervention programs.

Choosing Target Behaviors and Monitoring Them

Tkachuk, Leslie-Toogood, and Martin (2003) provide some guidelines and suggestions for selecting the behaviors to be changed and for observing and recording these behaviors. These include the following:

Intrinsic Motivation and Extrinsic Rewards

The world of sport and exercise uses extrinsic rewards extensively. Most leagues have postseason banquets in which participants receive such awards as medals, trophies, ribbons, money, and jackets. Elementary school teachers frequently give stickers and toys to reward good behavior in their students. Exercise participants, too, frequently get T-shirts and other rewards for regular attendance and participation in classes. Advocates of extrinsic rewards argue that rewards increase motivation, enhance learning, and increase the desire to continue participation. As noted throughout this chapter, the systematic use of rewards can certainly produce some desired behavior changes in sport, physical education, and exercise settings. However, if rewards are used incorrectly, some negative consequences also can result.

Types of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

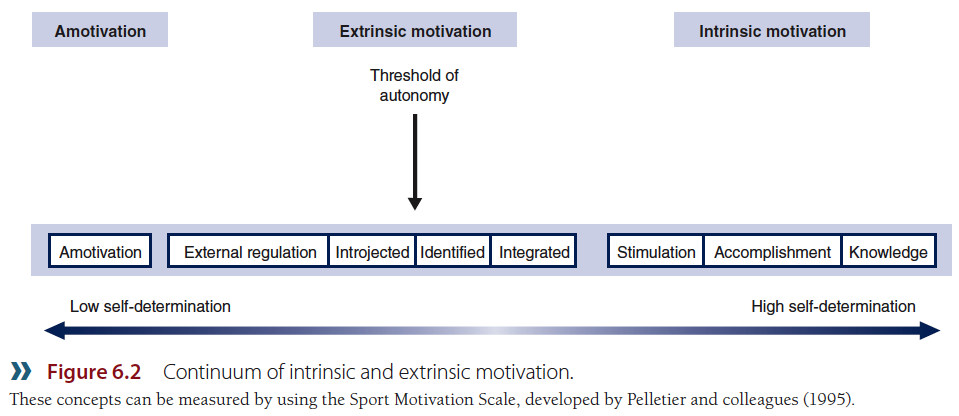

Current thinking views intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on a continuum and further elucidates different types of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (i.e., these constructs are viewed as multidimensional).

Intrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic Motivation

Amotivation

We know that motivation has two sources: extrinsic and intrinsic. With extrinsic rewards, the motivation comes from other people through positive and negative reinforcements. But individuals also participate in sport and physical activity for intrinsic reasons. People who have intrinsic motivation strive inwardly to be competent and self-determining in their quest to master the task at hand. They enjoy competition, like the action and excitement, focus on having fun, and want to learn skills to the best of their ability. Individuals who participate for the love of sport and exercise would be considered intrinsically motivated, as would those who play for pride. For example, when Steve Ovett, British elite middle-distance runner, was asked why he ran competitively, he answered, “I just did it because I wanted to … [get] the best out of myself for all the effort I’d put in” (Hemery, 1991, p. 142). Similarly, Tiger Woods observed that successful golfers “enjoy the serenity and the challenge of trying to beat their own personal records” (Scott 1999, p. 47). In fact, a recent study investigating sustained motivation of elite athletes (Mallet & Hanrahan, 2004) found that athletes were driven mainly by personal goals and achievements rather than financial incentives. But competing against and defeating an opponent is still important for some, as noted by this quote from Sam Lynch, World Rowing champion: “You don’t go for a world record in a race like this. It may come, but winning the title comes first” (Jones, 2002, p. 15). The current view of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is presented in figure 6.2 on page 140, and the different types of motivation are explained in “Types of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation.” We now turn our attention to what happens when we combine extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation.

Passion: A Key to Sustained Motivation

Although the concept of passion has generated a lot of attention among philosophers, it has only recently received empirical attention in the sport and exercise psychology literature. Passion has been defined as a strong inclination and desire toward an activity one likes, finds important, and invests time and energy in. In line with self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2002), it has been argued that when individuals like and engage in an activity on a regular basis, it will become part of their identity to the extent that it is highly valued (Vallerand et al., 2006). Thus, for example, having passion toward playing basketball would mean that one is not merely playing basketball; rather one is a basketball player.

Two types of passion have been identified (Vallerand et al., 2003).

These are key findings regarding passion and sport (Lafreniere et al., 2008; Vallerand et al., 2006):

Factors Affecting Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Both social and psychological factors can affect one’s intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in sport and exercise. Some of the more prominent social factors include (a) success and failure (experiences that help define one’s sense of competency), (b) focus of competition (competing against yourself and some standard of excellence, where improvement is the focus, vs. competing against your opponent, where the focus is on winning), and (c) coaches’ behaviors (positive vs. negative). Self-determination theory argues that competence, autonomy, and relatedness are the three basic human needs, and the degree to which they are satisfied will go a long way in determining an individual’s intrinsic motivation. Therefore, the psychological factors affecting motivation include (a) need for competence (to feel confident and self-efficacious), (b) need for autonomy (to have input into decisions or in some way “own” them), and (c) need for relatedness (to care for others and to have them care for you). Being aware of these factors and altering things when possible will enhance one’s feelings of intrinsic motivation.

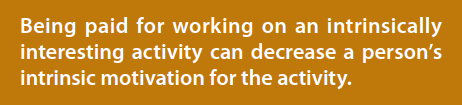

Do Extrinsic Rewards Undermine Intrinsic Motivation?

Intuitively, it seems that combining extrinsic and intrinsic motivation would produce more motivation. For instance, adding extrinsic rewards such as trophies to an activity that is intrinsically motivating (e.g., intramural volleyball) should increase motivation accordingly. Certainly you would not expect these extrinsic rewards to decrease intrinsic motivation. But let’s look further at the effect of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation.

Most early researchers and practitioners saw intrinsic and extrinsic motivation as additive: the more, the better. Some people, however, noted that extrinsic rewards could undermine intrinsic motivation. For example, Albert Einstein commented about exams, “This coercion had such a deterring effect that, after I passed the final examination, I found the consideration of any scientific problems distasteful to me for an entire year” (Bernstein, 1973, p. 88). When people see themselves as the cause of their behavior, they consider themselves intrinsically motivated. Conversely, when people perceive the cause of their behavior to be external to themselves (i.e., “I did it for the money”), they consider themselves extrinsically motivated. Often, the more an individual is extrinsically motivated, the less that person will be intrinsically motivated (deCharms, 1968).

What Research Says

In the late 1960s, researchers as well as theorists began to systematically test the relationship between extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation. Edward Deci (1971, 1972) found that participants who were rewarded with money for participating in an interesting activity subsequently spent less time at it than did people who were not paid. In his quite original and now classic study, Deci paid participants to play a Parker Brothers mechanical puzzle game called SOMA, which is composed of many different-shaped blocks that can be arranged to form various patterns (pilot testing had shown this game to be intrinsically motivating). In a later play period, the time these participants spent with the SOMA puzzles (as opposed to reading different interesting magazines) was significantly less (106 seconds) than the time (206 seconds) spent by individuals who had not been rewarded for playing with the puzzles.

In another early classic study called “Turning Play Into Work,” Lepper and Greene (1975) used nursery school children as participants and selected an activity that was intrinsically motivating for these children—drawing with felt pens. Each child was asked to draw under one of three reward conditions. In the “expected reward” condition, the children agreed to draw a picture in order to receive a Good Player certificate. In the “unexpected reward” condition, the award was given to unsuspecting children after they completed the task. In the “no-reward” condition, the children neither anticipated nor received an award. One week later, the children were unobtrusively observed for their interest in the same activity in a free-choice situation. The children who had drawn with the felt pen for expected rewards showed a decrease in intrinsic motivation, whereas the other two groups continued to use the felt pens just as much as they had before the experiment. When the expected reward was removed, the prime reason for the first group’s using the felt pen was also removed, although they had initially been intrinsically motivated to use the felt pen (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973). This study demonstrates potential long-term effects of extrinsic rewards and the importance of studying how the reward is administered.

Not all studies have shown that extrinsic rewards decrease intrinsic motivation. To the contrary, general psychological studies of the relationship between extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation have concluded that external rewards undermine intrinsic motivation under certain select circumstances—for example, recognizing someone merely for participating, without tying recognition to the quality of performance (Cameron & Pierce, 1994; Eisenberger & Cameron, 1996). However, Ryan and Deci (2000) debated this conclusion, arguing persuasively that the undermining effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation are much broader and wider reaching. Similarly, research conducted specifically within the sport and exercise domains reveals a number of instances in which extrinsic rewards and other incentives do indeed undermine and reduce intrinsic motivation (Vallerand, Deci, & Ryan, 1987; Vallerand & Losier, 1999). Thus, we need to understand under what conditions extrinsic rewards can negatively affect intrinsic motivation.

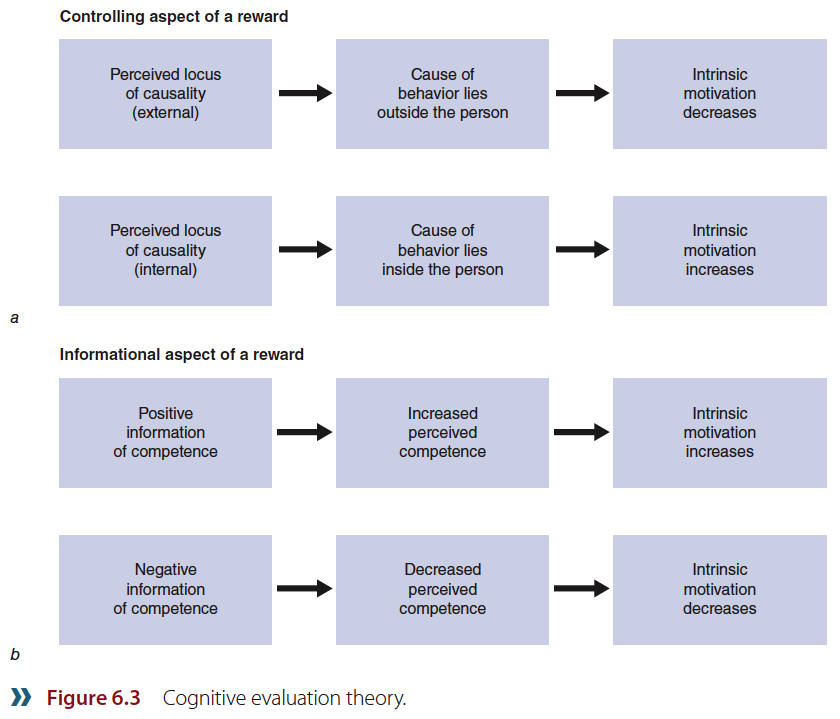

Cognitive Evaluation Theory

To help explain the different potential effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation, Deci and his colleagues developed a conceptual approach called cognitive evaluation theory (CET; Deci, 1975; Deci & Ryan, 1985). CET is really a subtheory of the more general self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Self-determination theory focuses on three basic psychological needs: the needs for effectance, relatedness, and autonomy. In essence, Deci and Ryan (1994) argued that “people are inherently motivated to feel connected to others within a social milieu (relatedness), to function effectively in that milieu (effectance) and to feel a sense of personal initiative in doing so (autonomy)” (p. 7). Therefore, intrinsic motivation, performance, and cognitive development are maximized within social contexts that provide people the opportunity to satisfy these basic needs.

Although SDT focuses on intrinsic motivation, it does not elaborate on what causes intrinsic motivation. Therefore, CET was developed to help explain the variability in intrinsic motivation. In essence, the focus is on the factors that facilitate or undermine the development of intrinsic motivation. Following the orientation of SDT, CET hypothesizes that any events that affect individuals’ perceptions of competence and feelings of self-determination ultimately will also affect their levels of intrinsic motivation. These events (e.g., distribution of rewards, the quantity and quality of feedback and reinforcement, and the ways in which situations are structured) have two functional components: a controlling aspect and an informational aspect. Both the informational and controlling aspects can increase or decrease intrinsic motivation, depending on how they affect one’s competence and self-determination (see figure 6.3).

Controlling Aspect of Rewards

The controlling aspect of rewards relates to an individual’s perceived locus of causality (i.e., what causes a person’s behavior) in the situation. If a reward is seen as controlling one’s behavior, then people believe that the cause of their behavior (an external locus of causality) resides outside themselves, and thus intrinsic motivation decreases.

People often feel a direct conflict between being controlled by someone’s use of rewards and their own needs for self-determination. That is, people who are intrinsically motivated feel that they do things because they want to, rather than for external reward. When people feel controlled by a reward (e.g., “I’m only playing for the money”), the reason for their behavior resides outside of themselves. For example, many college athletes feel controlled by the pressure to win, to compete for scholarships, and to conform to coaching demands and expectations. With the change to free agency in many professional sports, a number of athletes report feeling controlled by the large sums of money they earn. This in turn has led to their experiencing less enjoyment in the activity itself. Research has revealed six salient controlling strategies used by coaches to control athletes’ behaviors, thus undermining intrinsic motivation (Bartholomew, Ntoumanis, & Thogersen-Ntoumanis, 2009). These strategies include the

following:

1. Tangible rewards (e.g., a coach promises to reward athletes if they engage in certain training behaviors)

2. Controlling feedback (e.g., a coach who picks up on all the negative aspects of an athlete’s behavior but says nothing positive and offers no suggestions for future improvement)

3. Excessive personal control (e.g., a coach who interacts with athletes in an authoritative manner, commanding them to do things through the use of orders, directives, controlling questions, and deadlines)

4. Intimidation behaviors (e.g., a coach who uses the threat of punishment to push athletes to work harder or keep athletes in line during training)

5. Promoting ego-involvement (e.g., a coach who evaluates an athlete’s performance in front of their peers)

6. Conditional regard (e.g., a coach who says things to make athletes feel guilty, such as, “You let me down,” “When you don’t perform well…” etc.)

In contrast, if a reward is seen as contributing to an internal locus of causality (i.e., the cause of one’s behavior resides inside the person), intrinsic motivation will increase. In these situations individuals feel high levels of self-determination, perceiving their behavior as determined by their own internal motivation. For example, sport and exercise programs that provide individuals with opportunities for input about the choice of activities, personal performance goals, and team or class objectives result in higher intrinsic motivation because they increase personal perceptions of control (Vallerand et al., 1987).

Informational Aspect of Rewards

The informational aspect affects intrinsic motivation by altering how competent someone feels. When a person receives a reward for achievement, such as the Most Valuable Player award, this provides positive information about competence and should increase intrinsic motivation. In essence, for rewards to enhance intrinsic motivation, they should be contingent on specific levels of performance or behavior.

Moreover, rewards or events that provide negative information about competence should decrease perceived competence and intrinsic motivation. For example, if a coach’s style is predominantly critical, some participants may internalize it as negative information about their value and worth. This will decrease their enjoyment and intrinsic motivation. Similarly, striving for an award and not receiving it will decrease feelings of competence and lower intrinsic motivation.

Functional Significance of the Event

In addition to the controlling and informational aspects of rewards, a third major element in CET is the functional significance of the event (Ryan & Deci, 2002). In essence, every reward potentially has both controlling and informational aspects. How the reward will affect intrinsic motivation depends on whether the recipient perceives it to be more controlling or more informational. For example, on the surface it would seem positive to recognize individuals or teams with trophies. However, although the reward’s message seems to be about the athletes’ competence, the players may perceive that the coach is giving them rewards to control their behavior (i.e., make sure they don’t join another team next year). It must be clear to participants that a reward provides positive information about their competence and is not meant to control their behavior. In general, perceived choice and positive feedback bring out the informational aspect, whereas rewards, time deadlines, and surveillance make the controlling aspect salient.

Consider the example provided by Weiss and Chaumeton (1992) of a high school wrestler. According to the coach, the wrestler had a great deal of talent and potential, had won most of his matches, and had received positive feedback from the coach, teammates, and community. In addition, as a team captain, he had participated in developing team rules and practice regimens. Despite the amount of positive information conveyed about the student’s wrestling competence, the coach was baffled by the wrestler’s lack of positive affect, effort, persistence, and desire. It was only later that the coach found out that the boy’s father had exerted considerable pressure on him to join the wrestling team and was now living vicariously through his son’s success—while still criticizing him when he believed his son’s performance wasn’t up to par. Thus, the wrestler perceived the controlling aspect, emanating from his overbearing father, as more important than the positive feedback and rewards he was getting through his wrestling performance. The result was a perceived external locus of causality with a subsequent decrease in intrinsic motivation.

How Extrinsic Rewards Affect Intrinsic Motivation in Sport

Magic Johnson was once asked if he received any outrageous offers while being recruited by various college basketball teams. He responded, “I received my share of offers for cars and money. It immediately turned me off. It was like they were trying to buy me, and I don’t like anyone trying to buy me.” Notice that what Magic Johnson was really referring to was the controlling aspect of rewards. He did not like anyone trying to control him through bribes and other extrinsic incentives. With the outrageous multimillion-dollar long-term contracts that are currently being offered to many professional athletes, the natural question is whether athletes will lose their motivation and drive to perform at top level. Let’s look at what some of the research has found.

Scholarships and Intrinsic Motivation

One of the first assessments of how extrinsic rewards affect intrinsic motivation in a sport setting was Dean Ryan’s study of scholarship and nonscholarship collegiate football players (1977, 1980). Players on scholarship reported that they were enjoying football less than their nonscholarship counterparts. Moreover, scholarship football players exhibited less intrinsic motivation every year they held their scholarship, so their lowest level of enjoyment occurred during their senior year. Ryan later surveyed male and female athletes from different schools in a variety of sports (1980). Again, scholarship football players reported less intrinsic motivation than nonscholarship football players. However, male wrestlers and female athletes from six different sports who were on scholarship reported higher levels of intrinsic motivation than those who were not on scholarship.

These results can be explained by the distinction between the controlling and informational aspects of rewards. Scholarships can have an informational function—scholarships tell athletes that they are good. This would be especially informative to wrestlers and women, who receive far fewer scholarships than other athletes. Remember that in 1980, few athletic scholarships were available to wrestlers and women. In comparison, some 80 scholarships were awarded to Division I football teams, which would make the informational aspect of receiving a football scholarship less positive confirmation of outstanding competence.

Football is the prime revenue-producing sport for most universities. Consider how football scholarships, as well as scholarships in other revenue-producing sports, can be used. Some coaches may use scholarships as leverage to control the players’ behavior. Players often believe that they have to perform well or lose their scholarships. Sometimes players who are not performing up to the coaches’ expectations are made to participate in distasteful drills, are threatened with being dropped from the team, or are given no playing time. By holding scholarships over players’ heads, coaches have sometimes turned what used to be play into work. Under these conditions, the scholarship’s controlling aspect is more important than its informational aspect, which evidently decreases intrinsic motivation among the scholarship players.

Given the changing trends in both men’s and women’s collegiate sport during the 1980s and 1990s, a more recent study (Amorose, Horn, & Miller, 1994) addressed the role that scholarships have on intrinsic motivation. The investigation showed that among 440 male and female athletes in Division I, the players on scholarship had lower levels of intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, and perceived choice than their nonscholarship cohorts. This occurred with both the men and women, indicating that the growth of women’s collegiate sport may have raised the pressure to win to the level experienced in men’s collegiate athletics. Making more scholarships available to women athletes has reduced the informational aspect of these awards, and the concomitant pressure to win has enhanced the controlling aspect of scholarships, thus decreasing intrinsic motivation.

Along these lines, Amorose and Horn (2000) attempted to determine whether it was the scholarship itself or the actual coaching behaviors that produced changes in intrinsic motivation. In assessing how collegiate athletes perceived their coaches’ behavior, the authors found that changes in feelings of intrinsic motivation were primarily attributable to coaching behaviors rather than to whether an athlete was on scholarship. Specifically, athletes who perceived that their coaches exhibited predominantly positive and instructional feedback, as well as democratic and social support behaviors, exhibited higher levels of intrinsic motivation than athletes who perceived that their coaches displayed predominantly autocratic behaviors. Similarly, Hollembeak and Amorose (2005) found that democratic coaching behaviors produced higher levels of intrinsic motivation whereas autocratic coaching behaviors produced lower levels of intrinsic motivation. Thus, regarding intrinsic motivation, it appears that the type of coach one plays for is more important than whether one is on scholarship.

Competition and Intrinsic Motivation

Competitive success and failure can also affect intrinsic motivation. Specifically, competitive events contain both controlling and informational components, and thus they can influence both the perceived locus of causality and perceived competence of the participants. By manipulating the success and failure that participants perceive on a motor task, several researchers have revealed that people have higher levels of intrinsic motivation after success than after failure (Vallerand, Gauvin, & Halliwell, 1986a; Weinberg & Jackson, 1979; Weinberg & Ragan, 1979). Success and failure have high informational value in competition, and males exhibited significantly higher levels of intrinsic motivation after success than after failure. In contrast, females did not vary much across success and failure conditions, which suggests that competitive success is more important for males than for females (Deaux, 1985). When males succeed, they tend to feel good and to exhibit high intrinsic interest in the task, but when they lose, they also quickly lose interest and intrinsic motivation. Females appear less threatened by the information contained in competitive failure, likely because their egos are not typically as invested in displaying success as are those of their male counterparts. Recent changes in women’s sport, however, suggest that we should reexamine whether the participants still have these kinds of perceptions.

We tend to focus on who won or lost a competition, which represents the objective outcome. However, sometimes an athlete plays well but still loses to a superior opponent, whereas other times someone plays poorly but still wins over a weak opponent. These subjective outcomes also appear to determine an athlete’s intrinsic motivation. People who perceive that they performed well show higher levels of intrinsic motivation than those with lower perceptions of success (McAuley & Tammen, 1989). Winning and losing are less important in determining intrinsic motivation than people’s (subjective) perception of how well they performed. The adage “It’s not whether you win or lose, but how you play the game” applies in determining how a performance affects intrinsic motivation.

In essence, the focus of one’s performance appears to be more important than the actual outcome. For example, Vallerand, Gauvin, and Halliwell (1986b) found that youngsters who were asked to compete against another child (interpersonal competition) on a motor task exhibited less intrinsic motivation than those who were instructed to simply compete against themselves (mastery). Similarly, other research (Kavussanu & Roberts, 1996; Koka & Hein, 2003) indicated that intrinsic motivation was higher when participants viewed the motivational climate of their classes to be more mastery oriented than ego oriented.

Feedback and Intrinsic Motivation

Feedback and intrinsic motivation involve how positive and negative information from significant others affects your own perceived competence and subsequent intrinsic motivation. Vallerand’s (1983) first study investigated varying the amounts of positive feedback to adolescent hockey players who were performing in simulated hockey situations. Players received 0, 6, 12, 18, or 24 positive statements from coaches while performing various hockey skills. The groups who received feedback scored higher in perceived competence and intrinsic motivation than did the no-feedback group, although there were no differences among the various feedback groups. Therefore, the absolute quantity of positive feedback seems less important than the presence of at least some type of positive feedback.

A second study using a balance task also showed that positive feedback produced higher levels of intrinsic motivation than did negative feedback or no feedback (Vallerand & Reid, 1984). A more recent study (Mouratidis, Vansteenkiste, Lens, & Sideridis, 2008) showed that very positive feedback (“You’re one of the best in the class”) compared to mild positive feedback (“You’re about average”) produced significantly more intrinsic motivation and a greater intent to participate in similar activities in the future. These results underscore the importance of the quality of positive feedback and not just the amount.

Principles for the Effective Use of External Rewards

Other Determinants of Intrinsic Motivation

Besides the factors already noted, researchers have found a variety of other factors related to intrinsic motivation (see Vallerand & Rousseau, 2001, for a review). Thus, higher levels of intrinsic motivation appear to be related to

Strategies for Increasing Intrinsic Motivation

Inasmuch as rewards do not inherently undermine intrinsic motivation, coaches, physical educators, and exercise leaders do well to structure and use rewards and other strategies in ways that increase perceptions of success and competence and, by extension, the intrinsic motivation of the participants. Read the following suggestions for increasing intrinsic motivation, and analyze how the use of rewards provides participants with information that will increase their intrinsic motivation and perception of competence.

Flow—A Special Case of Intrinsic Motivation

Some of the most innovative studies of enhancing intrinsic motivation come from the work of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990). Whereas many researchers have tried to determine which factors undermine intrinsic motivation, Csikszentmihalyi investigated exactly what makes a task intrinsically motivating. He examined rock climbing, dancing, chess, music, and amateur athletics—all activities that people do with great intensity but usually for little or no external reward. In sport, Sue Jackson has led the research in this area, studying flow experiences in athletes from a variety of sports. Jackson and Csikszentmihalyi have also collaborated on a book, Flow in Sport: The Keys to Optimal Experiences and Performances (Jackson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). Through their research, Jackson and Csikszentmihalyi have identified a number of common elements that make sport activities intrinsically interesting. These essential elements of the flow state include the following:

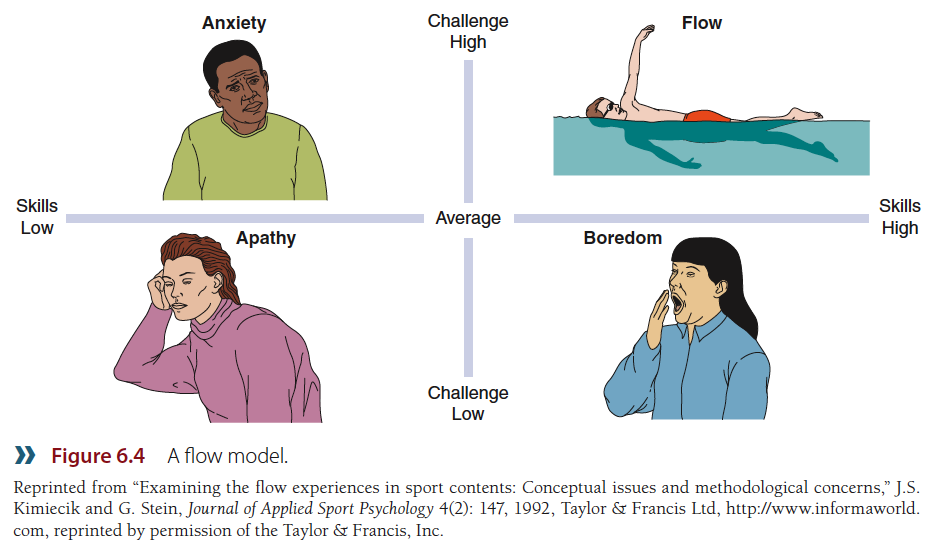

These elements represent the essential features of optimal performances, which athletes have described as “hot,” “in a groove,” “on a roll,” or “in the zone,” a special state where everything is going well and you’re hitting on all cylinders. Csikszentmihalyi calls this holistic sensation flow, in which people believe they are totally involved or on automatic pilot. He argued that the flow experience occurs when your skills are equal to your challenge. Intrinsic motivation is at its highest and maximum performance is achieved. However, if the task demands are greater than your capabilities, you become anxious and perform poorly. Conversely, if your skills are greater than the challenges of the task, you become bored and perform less well.

Figure 6.4 shows that flow is obtained when both capabilities (skills) and challenge are high. For example, if an athlete has a high skill level and the opponent is also highly skilled (e.g., high challenge), then the athlete may achieve flow. But if an athlete with less ability is matched against a strong opponent (high challenge), it will produce anxiety. Combining low skills and low challenge results in apathy, whereas high skills and low challenge result in boredom. Stavrou, Jackson, and Zervas (2007) tested the notion of these four quadrants and the achievement of optimal experience. Results revealed that participants in the flow and relaxation conditions exhibited the most optimal affective states and performance, whereas apathy produced the least optimal states (boredom was between apathy and flow). By structuring exercise classes, physical education, and competitive sports to be challenging and creative, you foster better performance, richer experiences, and longer involvement in physical activity.

How People Achieve Flow

If they knew how, coaches and teachers would likely want to help students and athletes achieve this narrow framework of flow. So the logical question is, How does one get into a flow state? Research studying athletes from different sports (Jackson, 1992, 1995) found that the following factors were most important for getting into flow:

Controllability of Flow States

Can individuals control the thoughts and feelings connected with flow? The athletes interviewed by Jackson (1992, 1995) varied in their responses regarding the controllability of their flow states. Overall, 79% perceived flow to be controllable, whereas 21% believed it was out of their control. Athletes who believed that flow was controllable made comments like these: “Yeah, I think you can increase it. It’s not a conscious effort. If you try to do it, it’s not going to work. I don’t think it’s something you can turn on and off like a light switch” (Jackson, 1992, p. 174). A triathlete noted, “I think I can set it up. You can set the scene for it, maybe with all that preparation. It should be something that you can ask of yourself and get into, I think, through your training and through your discipline” (Jackson, 1995, p. 158).

Some athletes, although considering flow to be controllable, placed qualifiers on whether it would actually occur. A javelin thrower captured this perception in his remark, “Yeah, it’s controllable, but it’s the battle between your conscious and subconscious, and you’ve got to tell your conscious to shut up and let the subconscious take over, which it will because it’s really powerful” (Jackson, 1995, p. 158). A rugby player believed that flow was not controllable in team sports: “It all comes back to the team—everybody, all the guys knotted in together and it just rolls along for 5, 10 minutes, half an hour, going very well, but then someone might lose concentration or go off beat or something and then you’d be out of that situation you were just in, and you can’t have any control over that” (Jackson, 1995, p. 159).

Jackson’s studies suggest that although athletes cannot control flow, they still can increase the probability of it occurring by following the guidelines stated here and focusing on things within their control, such as their mental preparation. Most enlightening is a study by Pates, Oliver, and Maynard (2001), who examined the effectiveness of hypnosis training on flow states and golf putting performance. The hypnosis training involved deep breathing, progressive relaxation, and a multisensory imagery type of experience focusing on best past performance and associated with a trigger cue. Findings revealed that the five golfers studied increased both their putting performance and flow scores after using hypnosis, showing that athletes can be trained to increase their flow experiences. In a study of 236 athletes Jackson, Thomas, Marsh, and Smethurst (2001) also found that flow was related not only to performance but to the psychological skills athletes typically use. Particularly, keeping control of one’s thoughts and emotions and maintaining an appropriate level of activation and relaxation were psychological skills related to flow.

Factors That Prevent and Disrupt Flow

Although we need to understand how to enhance the likelihood of flow’s occurrence, it is equally important to understand what factors may prevent or disrupt it (Jackson, 1995). These factors are identified in “Factors That Prevent and Disrupt Flow”. Despite some consistency in what prevents and what disrupts flow’s occurrence, individuals do experience differences between these situations. The factors athletes cited most often as preventing flow were less than optimal physical preparation, readiness, and environmental or situational conditions; the reasons they gave most often as disrupting the flow state were environmental and situational influences.

Professionals can try to structure the environment and provide feedback to maximize the possibility of athletes reaching and maintaining a flow state. However, participants themselves must be aware of the factors that influence the occurrence of the flow state so that they can mentally and physically prepare for competition and physical activity accordingly. They should distinguish factors that are under their control and that they can change (e.g., physical or mental preparation, focus of attention, negative self-talk) from those they can’t control (e.g., crowd responses, coach feedback, weather and field conditions, behavior of competitors). For example, an athlete can’t control a hostile crowd, but she can control how she reacts both mentally and emotionally to the crowd. Similarly, a physical therapist can’t control patients’ attitudes or how crowded a clinic is, but he can strive to maintain a positive attitude in his interactions with clients. Finally, increasing psychological skills such as arousal regulation, emotion management, and thought control increases one’s likelihood of experiencing flow.

Flow has thus far been presented as a very positive mental and emotional state associated with enhanced performance as well as positive affective states. However, recent research (Partington, Partington, & Oliver, 2009) has shown that the consequences of experiencing flow may not always be positive. The authors argue that one potential negative consequence might be that of contributing to dependence on an activity once associated with a flow experience. In interviewing surfers, they found that some exhibited characteristics of dependence on surfing much like habitual drug users who need to continually increase their dosage to gain the appropriate sensations (i.e., they needed to increase the size and speed of the wave they were surfing to recapture the feelings they had experienced previously). In fact, surfers talked of being addicted to the euphoric feelings they experienced, and were willing to continue to surf despite family commitments, injury, or potential death to replicate these sensations. Some surfers admitted being unable to function normally in society because of their involvement in surfing. This research simply highlights the “dark side” of flow, although in most cases, flow will turn out to be a very positive and performance-enhancing feeling state.

Factors That Prevent and Disrupt Flow

Preventive Factors

Disruptive Factors

Learning Aids

Summary

1. Explain how positive feedback and negative feedback influence behavior.

In discussing two basic approaches to reinforcement—positive and negative control—we recommend a positive approach, although punishment is sometimes necessary to change behavior. Several factors can make reinforcements more effective, including the choice of effective reinforcers, the schedule of reinforcements, and the choice of appropriate behaviors (including performance and social and emotional skills) to reinforce. Punishment has potential negative effects, such as creating a fear of failure or creating an aversive learning environment.

2. Understand how to implement behavior modification programs.

When we systematically use the principles of reinforcement to structure sport and exercise environments, the main goal is to help individuals stay task oriented and motivated throughout a training period.

3. Discuss the different types of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Contemporary thinking views intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on a continuum, from amotivation to various types of extrinsic motivation (introjected, identified, and integrated regulation) to different types of intrinsic motivation (knowledge, stimulation, accomplishment). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation are both viewed as multidimensional.

4. Describe the relationship between intrinsic motivation and external rewards (controlling and informational aspects).

Extrinsic rewards have the potential to undermine intrinsic motivation. Cognitive evaluation theory has demonstrated that extrinsic rewards can either increase or decrease intrinsic motivation, depending on whether the reward is more informational or controlling. Two examples of the effect of extrinsic incentives in sport are scholarships and winning and losing. If you want to enhance a participant’s intrinsic motivation, the key is to make rewards more informational.

5. Detail different ways to increase intrinsic motivation.

Coaches, teachers, and exercise leaders can enhance intrinsic motivation through several methods, such as using verbal and nonverbal praise, involving participants in decision making, setting realistic goals, making rewards contingent on performance, and varying the content and sequence of practice drills.

6. Describe how such factors as scholarships, coaching behaviors, competition, and feedback influence intrinsic motivation.

Research has revealed a variety of factors related to intrinsic motivation. For example, higher levels of intrinsic motivation are found for nonscholarship versus scholarship athletes, for democratic versus autocratic coaches, for recreational versus competitive environments, and for positive versus negative feedback.

7. Describe the flow state and how to achieve it.

A special state of flow epitomizes intrinsic motivation. This flow state contains many common elements, but a key aspect is that there is a balance between an individual’s perceived abilities and the challenge of the task. Several factors, such as confidence, optimal arousal, and focused attention, help us achieve a flow state; other factors, such as a self-critical attitude, distractions, and lack of preparation, can prevent or disrupt flow states. Psychological skills training has also been shown to facilitate flow.

Key Terms

reinforcement

intrinsic rewards

shaping

feedback

motivational feedback

instructional feedback

contingency management

behavioral coaching

behavior modification

backward chaining

extrinsic rewards

intrinsic motivation

integrated regulation

identified regulation

introjected regulation

amotivation

harmonious passion

obsessive passion

social factors

psychological factors

cognitive evaluation theory

locus of causality

flow

Review Questions

1. Discuss the two principles of reinforcement and explain why they are more complex than they first appear.

2. Discuss the differences between the positive and negative approaches to teaching and coaching. As evidenced by the research, which one is more beneficial and why?

3. Discuss three of the potential negative side effects of using punishment.

4. Discuss the different types of reinforcers and the effectiveness of continuous and intermittent reinforcement schedules.

5. Discuss three things other than success that a coach or physical educator might reinforce.

6. Discuss what you believe to be the three most important guidelines for implementing behavioral programs in sport and exercise settings.