“The fortunes of this day,” Sargent wrote after reaching Fort Jefferson, “will blacken a full page in the future annals of America.” And so for a time it seemed. Soon Americans from New Hampshire to Georgia were singing Sinclair’s Defeat, which would become one of the most popular songs in early 19th-century America.

For Washington, St Clair’s report recalled bitter memories. At Monongahela he had commanded the retreating British army’s rearguard. “Here,” he shouted at his secretary, Tobias Lear, “Yes, here on this very spot I took leave of him… I said ‘I will add but one word – beware of surprise.’” Washington soon regained his composure. “General St Clair,” he said, “shall have justice… I will receive him without displeasure. I shall hear him without prejudice.”

In the first congressional investigation in American history, Congress appointed a committee to determine the causes of the catastrophe. On November 4, 1791, St Clair should have been in a fort at Kekionga, awaiting with a garrison of 1,200 US Army regulars the onset of winter. More than 3,000 levies and militiamen, who had accompanied him on his advance, should have long since returned to their homes. He instead had been on a field 44 miles from Kekionga, unsure of his location, unaware of the Indians’ capacities or intentions, with an army of 1,700 starving, freezing, and mostly untrained men.

The committee’s report exonerated St Clair. The campaign’s success had depended upon a complex recruiting and logistical operation. The Americans had grossly underestimated its difficulty. For a campaign to commence at remote Fort Washington, they had allowed less than four months to assemble 4,000 officers and men who had not yet been recruited, and vast quantities of supplies that had not yet even been ordered.

Testimony of the surviving officers addressed the cascading series of supply and training failures that followed the decision. If he had received “cartridge paper in proper time,” St Clair told the committee, his soldiers would not have faced the enemy untrained. The axes available to build the trace and forts, Major David Ziegler testified, “when used would bend up like a dumpling.” The tents, which provided no protection from rain or snow, were “truly infamous.” Much of the gunpowder, ruined from storage in the tents, “would not carry a ball but a short distance.” Ziegler, who had served as an officer in Prussian, Russian and American armies, told the committee that he “never saw such a degree of trouble thrown on the shoulders of any other general that I have served with, as upon General St Clair.”

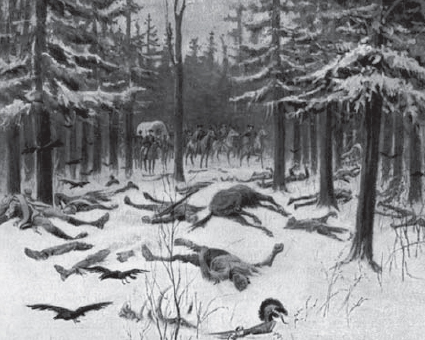

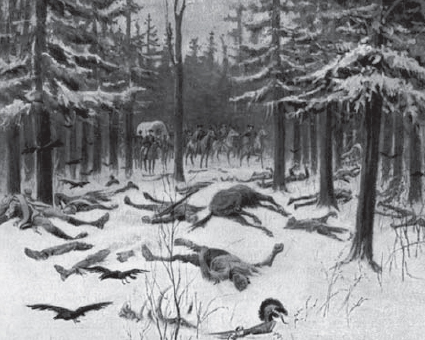

This Rufus F. Zogbaum engraving from Roosevelt’s St Clair’s Defeat shows the brief return of an American force to the battlefield on February 1, 1792. Sargent, who joined the expedition, wrote in his journal, “I was astonished to see the amazing effect of the enemy’s fire… Every twig and bush seems to be cut down, and the saplings and trees marked with the utmost profusion of shot.” (Photograph Courtesy of Harper’s Magazine)

This portrait of Henry Knox by Constantino Brunidi is in the US Capitol. (Architect of the Capitol)

St Clair’s ignorance of the area of operations added to the degree of trouble. Had he known that his road to Kekionga would be only 29 miles shorter than Harmar’s trace, not 55, his campaign likely would have taken a different course. “We had no guides,” he told the committee, “not a single person being found in the country who had ever been through it, and both the geography and topography were utterly unknown.”

The committee paid less attention to the battle itself. Some criticized the American commander for not building breastworks to protect his soldiers. The Indians, St Clair responded, then would have besieged rather than attacked the camp. His army, which had little food, would have had to leave the breastworks and fight the battle that occurred.

St Clair attributed the battle’s outcome to the low quality of his soldiers and overwhelming Indian numbers. Many of his soldiers, he said, “had never been in the woods in their lives.” It was, he added, “probably the first time to many of them that they fired a gun.” It also, he told the committee, “was physically impossible that an army posted as mine was, could be attacked in front and rear, and on both flanks, at the same instant, and that attack be kept up in every part for four hours without intermission, unless the enemy had been greatly superior in numbers.”

The Americans, however, had not been outnumbered. They had fought on a field on which they were especially vulnerable to the tactics the Indians used. By compressing his camp into such a small area, St Clair allowed the Indians to surround his army, and exposed the men in his lines to fire from all directions. By concentrating his artillery in only two locations, he made it possible for the Indians to focus the fire that suppressed it. By dispersing almost 500 men in detached camps and outposts, he allowed the Indians to render more than a quarter of his army unable to assist effectively in the camp’s defense. By failing to clear the surrounding woods, he dramatically diminished the ability of his army’s firepower to inflict on the Indians the casualties that would have forced them to withdraw.

St Clair blamed Knox, Hodgdon, and the army’s contractors for the supply and training failures that doomed his campaign. Many in Congress wanted to expand the committee proceedings into a broader investigation of the activities of Knox and the New York financier William Duer. Duer, a business partner of Knox and a friend of Alexander Hamilton, had aided in the financing of St Clair’s campaign, and received in return the army’s supply contract. In 1792 Duer’s financial empire collapsed. Afraid that further investigation might end in a scandal that would destroy the new national government under the US Constitution, Congress proceeded no further.

This room from St Clair’s house near Ligonier, Pennsylvania, is preserved at Fort Ligonier. (Fort Ligonier Staff Photo, Ligonier, Pa.)

This engraving from Henry Howe’s 1856 Historical Collections of the Great West depicts a December 24, 1791, attack by Indians on the cabin of John Merrill near Bardstown, Kentucky. After her husband fell wounded, the formidable Mrs Merrill saved her family by killing six of the eight attackers with an ax, and wounding another. (Author’s collection)

St Clair continued to serve as Governor of the Northwest Territory until 1802, when he retired to his estate in western Pennsylvania. He later lost his land when those to whom he had loaned money failed to pay their debts. By 1812 he was living in a small log cabin, where he died in 1818. “Mine,” he wrote in 1812, “was a laudable ambition, that of becoming the father of a country, and laying a foundation for the happiness of millions then unborn.”

After the battle of the Wabash, Lieutenant-Colonel James Wilkinson assumed command of what remained of the US Army on the Ohio River frontier. As he acted to ensure that Fort Jefferson and Fort Hamilton could be held, militia forces assembled to protect the larger forts and stations. The emboldened Indians, however, raided deep into the areas of American settlement. In desperate engagements at settlers’ cabins, American men, and often women and children, fought for their lives.

The response in Philadelphia proved the effectiveness of the new national government. As the Washington administration attempted to negotiate a peace treaty with the Indians it acted to create a force that could defeat them if negotiations failed. Congress appropriated funds for a new US Army, and enacted legislation that standardized the organization, equipment, and training of militia forces to conform with those of the US Army. Washington appointed Major-General Anthony Wayne as the US Army’s new leader, who was one of the most celebrated commanders of the Revolutionary War. The actions reassured the western settlers. Despite the Indian attacks, few on the frontier, even in the Northwest Territory, abandoned their settlements. In 1792, Kentucky followed Vermont into the union, as the 15th state.

Wayne then succeeded where St Clair had failed. Prolonged negotiations allowed him time to train his soldiers and to obtain the supplies needed for an effective campaign. The defection of William Wells, who led an effective corps of American scouts, allowed Wayne to advance with information on the area of operations and enemy as accurate as that available to Indian commanders.

The Miami Jean Baptiste de Richardville (Piniwa), and the Wyandot William Walker, Sr., (Sehstahroh) were among the young warriors at the battle who would become important figures in their tribes’ 19th-century histories. In 1790 Walker drew this sketch of the great Wyandot chief Tarhe. (Courtesy of the Wyandot County (Ohio) Historical Society)

In 1793, Wayne built a new headquarters for the US Armyat the site of St Clair’s 13th Camp, named Fort Greeneville. On December 25, 1793, the Americans began building at the site of the battle itself a symbol of national resolve, which Wayne named Fort Recovery. On June 30 and July 1, 1794, 2,000 Indians and British militiamen attacked, but failed to take, the exposed American outpost.

On August 20, 1794, the Americans had their revenge for the battle of the Wabash. At Fallen Timbers they routed an army of Indians and British militiamen. Wayne then constructed at Kekionga the fort that St Clair had failed to build, which would give Fort Wayne, Indiana, its name.

In 1795, the Indians surrendered in the Treaty of Greeneville all of what is now Ohio south of a line through Fort Recovery. In 1796 the British evacuated Detroit. In 1803 a part of the Northwest Territory entered the union as Ohio, the 17th state.

The Indian commanders who had defeated St Clair all opposed any further war with the Americans. Some younger leaders, however, disagreed. In 1805 thousands of Ohio Indians embraced a new religion revealed in visions of the Prophet (Tenskwatawa). He and his brother, Tecumseh, established Prophetstown, an Indian village larger than Kekionga, near the site of St Clair’s 13th Camp. In a campaign of witchcraft accusations, the Prophet’s followers attacked and killed many older Indian leaders.

In 1808 hostility by Americans and many Ohio Indians forced the Prophet and his followers to move to a new Prophetstown in Indiana. There, in 1811, they attacked an American army led by William Henry Harrison. The Americans, however, prevailed at the battle of Tippecanoe.

The War of 1812 followed. In 1813, a British army, and more than 2,000 Indians led by Tecumseh and the Wyandot chief Roundhead, invaded Ohio. An American army, led by Harrison, repelled them. American ships, commanded by Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry, destroyed a British fleet at the battle of Lake Erie.

An American army, which included hundreds of Ohio Wyandots and Shawnee led by Tarhe and Black Hoof, then invaded Ontario. On October 5, 1813, that army, commanded by Harrison, destroyed a British and Indian army at the battle of the Thames. There Tecumseh died, and war on the Ohio River frontier finally ended.