In chapter 3, we used a simple diagram to explain how reason and faith could be logically and systematically integrated. A single circle was used to represent dogmas or teachings of faith, and a single circle was used to represent dogmas or teachings of reason. But upon first encountering the world of faith, what one notices quickly is not “faith” but “faiths”—alternative, even competing sets of claims regarding what is to be believed. Likewise, upon first encountering the world of reason, what one notices quickly is not a single argument or claim based on reason, but multiple and competing claims. It might perhaps be objected, then, that the diagram in chapter 3 is just too simple to be helpful.

Our view is that the position that we began to explain in chapter 3 is true enough as far as it goes, but it is somewhat incomplete and needs to be made more sophisticated. It turns out that we will need to reconsider the singular groupings of faith and reason, addressing now the subdivisions of each. In other words, instead of “faith and reason”, we now turn to the question of “faiths and reasons”, or “faiths and philosophies”.

A. The Essence of Theism and Its Variations

In addressing this problem, let us begin with the region or circle in our diagram representing faith. As we all recognize, there are several sets of beliefs among people today; often these sets of beliefs are termed “religions”. Those sets of beliefs that have predominated among people and that have collected a number of adherents are often called “the world religions”. The list of “world religions” is greater or shorter depending on the criteria of the people making up the list, but all the lists include at least such sets of beliefs as Buddhism, Hinduism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Three of these sets of beliefs can be grouped together because they have a conception of God that shares many attributes and because they accept revelations of one sort or another. In other words, their basic understandings of God have a lot in common, and their basic teachings or dogmas are founded, they say, on a revelation. To be sure, there is plenty about which Judaism, Christianity, and Islam do not agree, but their basic conception of God is shared. We will have occasion to comment on this shared conception much more in the chapters that follow, but for now we will limit ourselves to saying that all three of these sets of beliefs understand God as the only God and understand God as the transcendent creator of the universe. They also think that God is personal, a being possessed of reason and will, and they think that the universe is causally dependent upon this being. Indeed, they think that God could exist without the world existing but that the world could not exist without God existing. This conception of God is called theism. Thus, we should say that all three of these sets of doctrines are “theistic” because they all three share a fundamental conception of God.

When we use the very term “God”, it is a theistic conception that will come to mind for most of our readers, for we anticipate that most of our readers will have already heard something about God and will have therefore absorbed an idea—probably a rather vague and nebulous one—about God. Probably they will have absorbed this idea from one of the famous three theistic sets of beliefs. It may therefore surprise some of our readers to learn that some of the other “world religions” cannot be termed “theistic”. Clearly polytheism, with its belief in a multiplicity of gods, differs from all theistic religions, but probably the principal alternative to theism in our time is pantheism. We will say a little more about pantheism later on, but for now we will simply say that the principal claim of pantheism is that the world and God are one, so much so that not only could the world not exist without God, but God could not exist without the world. There is thus no transcendent God with reason and will in pantheism, and, therefore, it is not at all obvious that the very word “God” should even be used within pantheism, and some forms of pantheism understandably reject the word. In the world today, some of the Eastern religions are often said to be pantheistic, or at least to contain some elements that are pantheistic.

The three theistic sets of beliefs mentioned above—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—are unique not only because of their common conception of God and God’s relationship to the world, but also because they accept that God has revealed himself to man in a manner that can be grasped fully only through faith and not through reason or philosophy alone. While the fundamental notion of God is similar in these three revelations, there is also much that these three revelations do not share. Consequently, instead of a diagram wherein faith is represented by a single circle, perhaps we should have a diagram wherein faith is represented by three circles, one each for Judaism, for Christianity, and for Islam:

What this diagram is meant to show is that there are some theistic doctrines shared by all three of these sets of beliefs, but there are also some doctrines unique to one of the sets of beliefs, and some unique to two of the three. Thus, that God is the creator and cause of the universe is a theistic doctrine shared by all three; that God spoke definitively through the prophet Muhammad and that this revelation is recorded definitively in the Qur’an is a teaching unique to Islam and not shared by Christianity or Judaism. That the second Person of the divine Trinity was incarnate in the person of Christ Jesus is a teaching unique to Christianity and not shared by either of the other two. That the Book of Jeremiah should belong to the canonical list of sacred texts is a belief shared by both Jews and Christians, but not Muslims. And other examples could be produced for the other regions of the diagram.

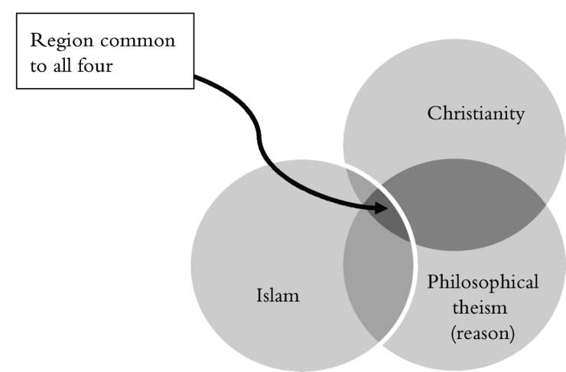

Our diagram is not complete, however, for the diagram in chapter 3 also contained a circle representing reason, and the diagram above does not. The illustrative value of these diagrams begins to break down as one moves beyond three circles, but let us draw a fourth one anyway, as it should still be helpful for explaining our point:

The circle representing “reason” is now also labeled philosophical theism. This is because there are some philosophers in the world who, pursuing only arguments based on reason, have reached conclusions about God that are basically the same as those conceptions of God that are common in the three religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In other words, there are thinkers in the world who do not accept through faith any of the revelations of Judaism, Christianity, or Islam, but who do think that God is the sole cause of the existence of the world and that God is a being with reason and will and who accept the other basic teachings of theism. According to our diagram, then, there are four principal existing options within the world of theism: Judaic theism, Christian theism, Islamic theism, and philosophical theism. These four are fundamental in that they are not reducible to each other, for each group either accepts doctrines from revelation that are incompatible with the other groups (the first three in our list) or rejects all such doctrines from revelation (the latter). All four do share, however, a common core teaching about the nature of God, and for this reason we can refer to the four as being “theistic” or as being the fundamental options within theism.

B. Clarifications regarding Revealed and Philosophical Theism

Now, it can immediately be objected that, just as our diagram from chapter 3 turned out to be too simple, so does this diagram from chapter 4. For there are divisions within, for example, Christianity. There are Protestants, Catholics, and Eastern Orthodox Christians, among others. And then the Protestant Christians can be further divided into Lutherans, Reformed, Methodists, and so forth. Similar divisions exist within Judaism and Islam. Ultimately, it would be impossible to draw an intelligible diagram that included all the possible permutations of revealed theism.

Still, it is not misleading to suggest that these many varieties of revealed theistic religions reduce to three principal ones. To be sure, a person who accepts that Judaism is fundamentally right, for example, will still need to answer the question of just which form of Judaism to follow. But conservative Jews, reformed Jews, and orthodox Jews are all in some sense Jews, just as Methodist Christians, Presbyterian Christians, and Episcopalian Christians are all in some sense Christians. Perhaps one of these subgroups understands its faith better than the others and is to be preferred, but it is still possible to categorize the three fundamental options within the world of revealed theism in this way.

It can also be objected that our new diagram is too simple because it still includes only a single circle for philosophical theism, whereas there are a great many philosophical theists. It is easy enough to argue, though, that while there are some variations among all those philosophers who are philosophical theists, they are in agreement on the most fundamental points and can thus, for present purposes, be classified as a single group. The situation with philosophical theists is rather different from the situation with revealed theists (that is, Jews, Muslims, and Christians). The Jewish, Christian, and Islamic revelations make a great many claims that are incompatible and inconsistent with each other. The region common to all three, while important, is really rather “small”, and hence it would be misleading not to have three circles. Within philosophical theism, the region of agreement is really much “larger”, and hence only a single circle is required.

In addition to the objection that there ought to be more than three circles for theistic religions, and in addition to the objection that there ought to be more than one circle for theistic philosophy, a third and more fundamental objection can be raised: Why limit the diagram to theistic religions and to theistic philosophy only? Why not include nontheistic religions and philosophies? This objection misunderstands our purpose in this book so far, however. Indeed, to this point, we have not given any argument for preferring theism in any of its forms to any nontheistic religion or nontheistic philosophy. What we are doing, instead, is explaining that, for all theists, if faith and reason can be integrated, that integration will need to consist of integrating theistic religion with theistic philosophy or, stated differently, religious theism with philosophical theism. We are outlining what the integration of faith and reason will have to look like for a theist. We have not said that theism is true, let alone that the proposed integration has been achieved. We have only said that if theism should turn out to be true, integrating faith and reason will turn out to correspond to our diagram with four circles. If there is something to be said for our explanation of the problem so far, however, it follows that the arguments that arise in our book as we move along should be supportive of all four of the basic theistic positions that we have listed, and in fact this will turn out to be the case. To be sure, the authors of this book are Christians, and we anticipate that our audience will primarily consist of Christians, and so we will be inclined to use Christian examples and mention Christian matters—especially Catholic ones—as we go forward. Still, there is no denying that almost all our arguments and discussions would support Islam and Judaism as well as Christianity. Indeed, if Thomas Aquinas is the standard-bearer with respect to the Christian position on the integration of faith and reason, it should be noted that Thomas freely borrowed arguments he found in the writings of such Jewish thinkers as Moses Maimonides and such Islamic thinkers as Avicenna. We should not, moreover, be especially surprised that there are some striking similarities in the positions reached, apparently independently, by the Jewish theologian Saadya Gaon and Thomas Aquinas.

In fact, in most of the following chapters what we will be articulating are the arguments simply of philosophical theism. Only rarely will we be appealing to revelation to support theism; we will, for the most part, write as philosophers or natural theologians or philosophical theologians rather than as believers. Since we are in fact Christians, though, we ultimately think that the diagram presented in chapter 3 is just fine. That is, for ourselves, we really do need only one circle for the truths accepted by faith in revelation and one circle for truths known through human reason or philosophy. And we would point out that the believing Muslim, for example, should think that he needs only the diagram from chapter 3 also. The Muslim’s circle representing doctrines accepted by faith in revelation is going to contain some different elements from the Christian’s circle, but the believing Muslim will still need the two circles of faith and reason, as will the believing Jew. The basic outline of the integrative position on faith and reason will apply to all the theistic religions, even if the circle containing the teachings or doctrines known through faith would be somewhat different for each of the three faith traditions.