17

MY BEAUTIFUL DARK TWISTED REALITY

One afternoon in October 2008, Usher called me at Island Def Jam. Though we hadn’t worked together since I’d left Arista, we remained close and spoke all the time. Over the years as he’d gotten older, ours had become much more of a friendship—especially since he was on a different label. He even still lived in my old home in Country Club of the South—a house that when he’d first entered at age fourteen, he’d looked around and announced, “Someday I’m going to own this.” Damned if he didn’t buy the place six years later.

As I’d tried to recover from Shakir’s suicide, Usher and I talked quite a bit, and though those first weeks and months getting back on the job had been difficult, support from people like Usher had made the difference. By the time I got the call from Usher that day in the fall of 2008, I was finally beginning to feel like myself again—both at home and at work—using music to bring me back to how all this began. While I had learned a lot about making art from Jay Z, and I now thought much more about the transformative power of music, as I came back from these dark times what I needed most was something catchy and familiar, something that would make me look to the future instead of the past. What I really needed was a new star.

As Usher and I spoke on the phone, he asked if I was going to be in my office all afternoon because he had something he wanted to bring me. We often exchanged gifts, so I had no idea what to expect. Was he bringing me another painting or what? He told me to expect him at four o’clock.

At four on the dot, Usher walked into my office with this adorable fourteen-year-old boy. This kid was beautiful, like a woman can be beautiful and men rarely are, and he turned it on as soon as he stepped into the room. No one introduced him—he just sat down at the piano and started singing, then he took out his guitar and sang some more. He talked a little bit, almost like it was a nightclub act or something—punctuating his performance with pieces of conversation and storytelling before returning to pounding a rhythm on the desk and singing along. I looked over at Usher and gave him a silent “Whoa!”

“This is Justin Bieber,” Usher said.

Fifteen years before, Usher had been the fourteen-year-old standing in front of my desk, and here he was now, an elder statesman of the tribe, the superstar I’d glimpsed all those years before in my office at LaFace, standing there with another kid almost the exact same age as Usher had been when he first met me. Usher didn’t just bring me a kid with an amazing voice, he brought me a born entertainer, someone who would become the biggest of them all. When Usher said he had a gift, he wasn’t kidding.

I always knew that if you left the door open and the lights on, something great will walk into your office. That’s the day it became true. Justin had already started to become famous on YouTube. He built a fan base by putting up videos of himself doing all these classic R&B songs by artists like Ne-Yo and Boyz II Men. I knew what to do.

“I’d like to sign him right away,” I said. “The sooner the better.”

Since he was a minor, it took a couple of days to get his parents involved and signed off. Justin’s manager was an Atlanta-based gentleman I had never met before, Scooter Braun, who discovered Justin from the YouTube videos Justin had posted. Within a week of bringing him to Atlanta, Scooter had Justin singing for Usher.

The next time Scooter and Justin turned up at my office, Justin had grown his hair down almost covering his eyes—a catchy look that was all his own. As with Avril Lavigne’s undershirt, and TLC and the condoms, I always looked for artists who could turn their style into a hook, but I was especially interested in hair. Hairstyles had done a lot for artists I had worked with as diverse as Toni Braxton and Pink, and I could see immediately that Justin’s hair would be every bit as important as his songs, his voice, his face, or his presence. It might not have been an intentional hairstyle, just that he hadn’t had his hair cut in a while, but I knew right at that moment that when this guy hit the marketplace, kids were going to soon be wearing their hair like his. That boy had a hit haircut.

A gift from Usher—the day we signed Justin Bieber, with Usher and manager Scooter Braun

Justin was simply beautiful—his superpower was his face. But his hair and his appearance were only part of his charm. Justin had all this natural charisma that instantly transformed him into his own character. Whereas other artists had to work to develop the persona that they wanted to project, he was loveable and lively from the start, radiating personality.

As I listened to what he was working on in the studio, I was delighted to hear all those pieces I’d been impressed with in person coming through on the recording as well. I loved the demos, especially one song called “One Time” that we got from Tricky, which I knew would be our first single.

On the album, we took Justin more R&B than pop, taking off from the kind of songs he was singing on his YouTube videos. He was a natural-born blue-eyed soul singer, and I’ve always known they can have extraordinary impact, long before I recorded Pink. We didn’t want him crooning and we did include pop songs on the album, but we cast him as an R&B singer. I heard this one song, “U Smile” and immediately wanted it for Justin. Unfortunately, the song belonged to another artist named Musiq Soulchild on Atlantic Records. The song had been written during an Atlantic writing camp, so Atlantic clearly outright owned this song. I didn’t give a damn. I did everything I had to do to acquire the rights. I spoke to everyone I knew at Atlantic and basically bought the song for Justin.

In part because of Justin’s age, but also because his YouTube videos had given him such a strong online fan base, we knew from the start that this record release was going to have a different look and feel to it—we had to figure out how to turn his age into an asset. When we put out the record in July 2009, we didn’t get a ton of radio traction—even though it had been years since Usher first came onto the scene, the stigma against teenage artists was still there. Radio needed to be coaxed to put Justin’s record on the air because his voice sounded so young that program directors thought he was more appropriate for Disney radio or Nickelodeon. Kids sound like kids, and radio doesn’t like that, so we didn’t get a lot of instant radio airplay. But Scooter took Justin on a promotional tour, visiting radio stations, and every time they went to a radio station, the crowd at the station would get bigger and bigger. Scooter and I developed a relationship. He would call and tell me there were thirty kids waiting at the station, and the next week he would call and say there were seventy-five.

In addition to the growing crowds, the video for “U Smile” became an instant hit online, encouraging us to keep using that medium to get Justin out there. On the album, Tricky and The-Dream had come up with a song they called “Baby Baby Baby,” which we shortened to “Baby.” As soon as I heard the song, I knew we would have a runaway smash. At the label, there was some controversy over the choice of the song as the next single. A couple of the executives didn’t think it was the right song. I looked at them like they were crazy, but I was learning to defer to my staff, so I may have allowed the discussion to continue further along than I would have otherwise. One of the other executives settled the matter.

“I only want to know what you think the single is,” she said, speaking to me. “I didn’t come to work here for what anyone else thinks except you.”

We made a video for “Baby” and the track blew straight to number one on iTunes when it was released in January 2010, where it ruled for weeks. The video turned into the biggest music video in YouTube history, with more than a billion plays. This kid, Justin Bieber, was simply an instant phenomenon at that point. Girls went wild. It was Biebermania. These kids went mad for this guy. Everywhere he went, mobs. No artist got more media scrutiny. Everything about him was amplified. Justin coughed, they said he’s got pneumonia.

The more Justin built social media into his approach, the more his persona took on a new life. Justin and Scooter were a couple of the first artists to use Twitter, which he used to announce an in-store appearance at a kids clothing store on Long Island called Justice. The day of the event, Justin kept tweeting, “I’m on my way.” The more he tweeted, the more people showed up at this mall. The place was packed with kids, thousands of them. The crowd grew impolite and police got nervous. They decided to close the mall and arrested the Def Jam sales representative Jim Roppo. Justin, by the way, never showed up.

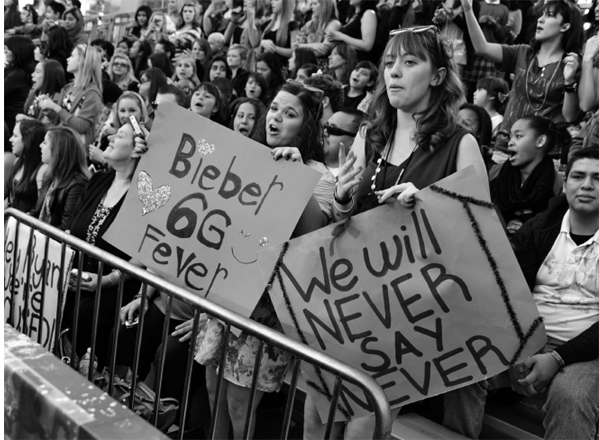

Biebermania outside the premiere of Never Say Never in Los Angeles (Kevin Winter/Getty Images)

It was Friday afternoon and the banks were closed. The cops were taking my mild-mannered sales rep to jail. I got a call telling me all this while I was on my way to a meeting at Mariah Carey’s penthouse. I borrowed whatever cash she had and gave it to my lawyer, who whisked over to spring Roppo before the weekend, but he was too late. Roppo spent the weekend in jail, so we made “Free Roppo” T-shirts. That incident was when we first realized how powerful the Justin Bieber phenomenon had become. And how powerful social media could be.

Justin arrived at the beginning of a new era. Social media had already caught on with his audience faster than it had with the record company marketing geniuses. By the time the Web-driven groundswell had built up behind Justin, radio was late to the game and could only play catch-up. He rewrote the radio-dominant playbook that had ruled pop music until that point. We were finding new avenues for artists to connect with an audience.

While at the time we were still understanding the implications for all this, looking back it’s easy to see what a transformative moment this release was. Justin wasn’t just a new pop star, he broke new ground. In some ways the release was as it always had been—videos, singles, radio—but with Justin we were able to elaborate on that longstanding blueprint in a unique way. His age gave us the opportunity to reach younger kids who weren’t listening to the radio but were just starting out online. That’s not to say that there hadn’t been hits that had begun online before, but a convergence of factors in this moment made Justin the ideal figure to become the first pop star created largely by social media.

For one thing, his age, which before social media would have been a detriment, was part of his success. But more than that, he was one of the first artists who did not hesitate to meet his audience in their own space and on their own terms. Though now it feels commonplace, in 2008 there was a lot of resistance among artists—and their managers, agents, and record companies—when it came to sharing themselves online. At the label, we were still learning about it ourselves, but just like when we were working with an artist who had a vision for the music, we knew when to take a step back. Because he was the same age as these kids, Justin had none of that hesitation, and it fueled every part of his rise, the first real star to emerge from the other side of the digital domain.

Through it all, Justin remained the sweetest kid. He would come to my office and hang, shoot pool, play checkers or backgammon. He was a prankster and he would run around the office like a little boy. Everybody liked Justin. This tidal wave of success was all the more reassuring to me because, after my awful mistake of releasing Lady Gaga, Justin simply walked into my office ready to go. I felt a little vindicated (although if I hadn’t dropped Lady Gaga, I would have had the two most successful artists of the time). Justin may have gotten started by playing his guitar on sidewalks in Toronto, but within a few months of signing with me he’d become the biggest star in the world.

Scooter, Justin, Pete Wentz, Kristinia DeBarge, and Kenny at Island Def Jam’s Spring Collection at Stephen Weiss Studio (Theo Wargo/Getty Images)

By the time we sold a few million copies of his debut album, My World, Scooter announced Justin’s first tour, and one of the first dates they put up for sale, Madison Square Garden, went clean in minutes. The entire tour sold out. He was the king of thirteen- and fourteen-year-old girls (and a few of their cougar mothers, too). I came up with the crazy idea of filming the Madison Square Garden shows for a concert movie. I could tell this was going to be a peak moment, and if Justin was going to be the Beatles, he needed his Hard Day’s Night. Scooter didn’t mind filming the shows, but he didn’t like the idea of making a movie, because he thought too much would be riding on whether the movie was a success or not and he didn’t want to take the risk. I understood his point of view, but didn’t necessarily agree.

“Maybe you don’t know how big your artist is,” I told him.

I’d been around record industry success long enough to understand just how unique a situation this was. Justin was a bona fide teen scream sensation the scale of which I had never before witnessed: packed houses of crying, yelling girls, heavy security details, massive press coverage. I could see this was bigger than simply hit records—that was why we should make the movie. He went off like an atom bomb and I watched from ground zero. I knew that he had what it took to launch a movie, even if Scooter wasn’t convinced.

We found some interest at Paramount Pictures—in fact, they got excited about making a movie with Justin Bieber. Scooter remained apprehensive, but I went ahead and set up a meeting at Paramount. Scooter could be the next David Geffen—that is how brilliant I think he is—but he was very reluctant to make this movie and wasn’t too keen on meeting anybody. Always prompt at our previous meetings, Scooter showed up an hour late. Eventually I dragged him into the room and made a deal for the movie.

We drove up to Hartford, Connecticut, for the first date of the tour. Backstage, Justin was goofing around with video games and playing basketball. A year before, he was this little kid who came to my office and now he was headlining an arena tour with buses and trucks parked outside. And here he was backstage shooting baskets like any other kid his age.

We did a 3-D movie with director Jon M. Chu, shot concert footage over a couple of nights in August 2010 at Madison Square Garden. The kids knew every song on the album and sang along with every lyric. Justin’s vocal performance was excellent and his stage presence was killer, but more than that, he was comfortable. He looked like he’d been doing it his entire life. Justin’s mother had been shooting footage of Justin since he was a baby, which Chu skillfully edited into the concert action. We called the movie Never Say Never, and when it was released the following year, it went on to become a $100 million smash at the box office, still the largest-grossing concert film.

While Justin became a pop artist who successfully blurred the lines with R&B for the Island side, Rihanna experienced similar success with a sound that moved her from R&B to pop for Def Jam. I’d been watching pop and R&B change over the years, but it wasn’t until Rihanna emerged as one of the biggest stars on the label that I came to see just how close to pop it had become and how oversimplified those old categories were.

After we’d signed Rihanna, Jay’s more than capable A&R staff scored a sizable hit on her first album, “Pon de Replay,” one of the songs she’d sang at her audition. After they started work on her second album, Jay’s man Jay Brown came to my office and played me a demo of a song, “SOS,” and I went crazy. That was about all I had to do with her second album, but once that record hit, I paid close attention. I told the A&R people I wanted to hear every song. Before I would have listened to her records only after they were done, but I sensed that she was on the brink, maturing as an artist and also as a person. By the time she went in to record her third album, I saw the opportunity to lift Rihanna to a new level in her career, and with a massive breakthrough only around the corner, she and I started to develop a relationship based on mutual respect and trust.

For her third album, Tricky Stewart and his writing partner, The-Dream, brought us “Umbrella,” a song they’d originally envisioned for Britney Spears until her label rejected the number. They’d also shown it to Mary J. Blige, but the minute Karen Kwak brought the song to me, I knew it was perfect for Rihanna. I had to fight to get the song, but I made them an offer they couldn’t refuse. Jay Z added a memorable rap to the recording and the song topped the charts for seven straight weeks after it was released in March 2007.

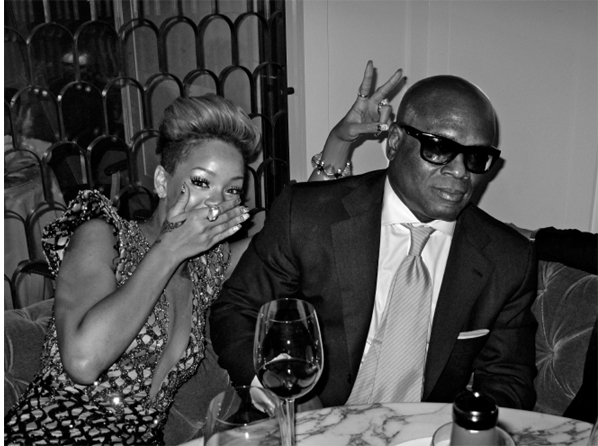

With Rihanna at my Grammy dinner party at Cecconis, Los Angeles

Our relationship really blossomed after “Umbrella.” Rihanna started coming to my office and we would discuss her follow-up. Now that she was officially a superstar, she began to make decisions about her career, communicating more with me about music. From that point forward, I challenged her, and we gradually grew closer and closer, almost like a father-daughter relationship. She is an amazing talent with an extraordinary ear for songs and instinct for her music. One of the few international pop singers since Bob Marley to sing in their native Caribbean dialect, she has a powerful inflection that she doesn’t hide. There’s a freedom in her to live her life and express herself that is incredibly rare, but the more I got to know her, the more I understood that her excitement for life isn’t limited to her art. She has the best taste in everything—from wine to music—and always seems to know what she wants.

I was sitting around my new house in the Hamptons with a couple of my A&R people, smoking some weed and listening to the new Rihanna album in the final stages. When we heard the song “Good Girl Gone Bad,” I knew I had found the title for her album. I had no idea how ironic that would become.

Rihanna invited me to her concert at Staples Center and played me a new song, “Disturbia,” in her dressing room, which I immediately knew would be a smash. We added the cut as a bonus track to the repackaged Good Girl Gone Bad and rushed it out as the next single. I was glad to see her take charge of her own career and that she knew what a hit sounded like.

She was set to perform at the Grammys in February 2009. The producer of the show reached me in my suite at the Beverly Hills Hotel the day before the Grammys. Rihanna had not showed for the rehearsal, he told me. The next phone call came from a publicist who worked for us. “Rihanna just had a car accident,” she said. “That’s all I can tell you right now, but she’s in the hospital.”

As it turned out it wasn’t a car accident, it was her incident with Chris Brown. I never knew much more about what happened than the public did. The details were kept from me. I saw the photos of her battered face the same time everybody else did. I managed to get through to Rihanna at the hospital, but it was a brief conversation. I was able to voice some concern, which I hoped was comforting, but I felt helpless. She was in bad shape and embarrassed, and didn’t want any visitors. All this was happening in her life at the point where she was moving beyond simply being a pop star with some hits into a lady the world cared about. It was tragic.

Several weeks later, her manager called to say Rihanna was coming to New York and wanted to see me, which somewhat surprised me. The fact that she was making my house her first stop in New York showed me that apparently our relationship was stronger than I had realized. It wasn’t until then that I saw just how close we’d become.

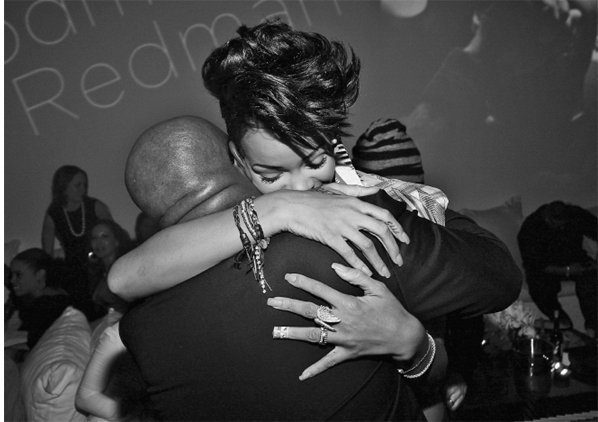

Holding RiRi (Theo Wargo/Getty Images)

She flew into town on a private jet, but the paparazzi still found her. She came straight to my apartment and they swarmed outside my building. I didn’t ask her too much about what happened. We talked mostly about what her next career step would be. I ordered some Caribbean food and we listened to music. I played her a couple of demos, but there wasn’t a lot of talk—most of our communication was telepathic. My only advice to her was to turn to music—it sounded cliché but that was what had gotten me through dark times. She stayed for hours. She already had her own A&R team—which I wasn’t part of, although I was the head of the company. We decided to start working together more.

She had stayed at my house so long, I was late for a meeting with Bon Jovi at a private club up the street. I delicately extricated myself and told her to feel free to stay at my house after I left. Later, Erica told me she stayed another couple of hours.

Sometimes an artist needs help making art, sometimes an artist needs help making a hit, and sometimes an artist just needs help.

While Justin’s and Rihanna’s success reconfirmed everything about my pop music instincts, it was with Kanye West that I’d been able to continue to witness the artistry behind the music, culminating with the album that would become his masterpiece.

Not long after I took over as chairman of Island Def Jam, Kanye quickly became my favorite artist on the label. I had originally known him as a producer. We’d first met when I was the president of Arista Records and he was producing an artist we’d signed named Lupe Fiasco from Chicago. He came with Lupe for his audition, and after I agreed to sign the act, the A&R guy who brought them told me that Kanye was also looking for a record deal. Kanye ended up signing with the Roc-A-Fella label, where he served as house producer and was only reluctantly allowed to experiment with his own recordings. Throughout all of this, it was clear he had talent, but I wasn’t sure that he was ready to step out in front of the mic.

That opinion changed quite a bit after our warm conversation at the Grammys the day I took over at Def Jam. Even though Kanye and I had held only a quick, simple discussion, this time, from those few words we exchanged, I could see he had the drive of somebody who was going to be a star. I had missed that completely at our first meeting. At first glance, Kanye wasn’t someone you would expect to become one of the most important artists of our time, mostly because he wasn’t what you’d come to expect from hip-hop. He carried his beats in a Gucci backpack. He didn’t wear the hip-hop uniform. He was a preppy fashionista. He wasn’t ghetto. His mother raised him well and he went to college. His first album was called The College Dropout. He was a new breed of hip-hop.

With Doug Morris, Bieber, and Rihanna at the launch of Doug’s brainchild VEVO, New York (Theo Wargo/Getty Images)

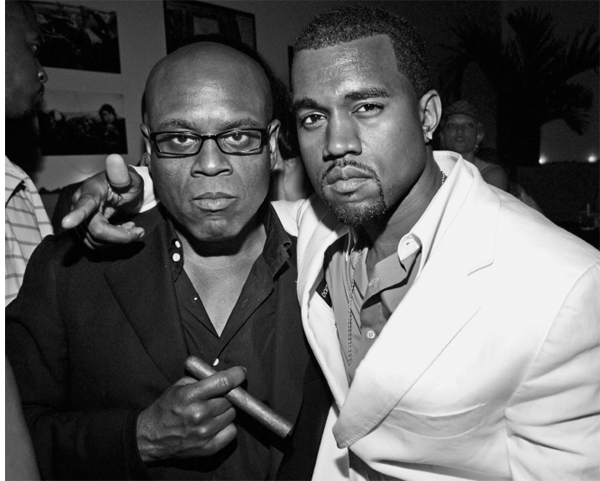

With Kanye at the Soho Grand Hotel, New York (KMazur/Getty Images)

I got a copy of The College Dropout immediately upon joining Island Def Jam and listened to it constantly—in my car, my hotel room, my apartment. It was an album that just stopped me in my tracks—it was that good. He had a song called “Jesus Walks” that took what was basically a straightforward declaration of religious beliefs into the Top Twenty. It wasn’t just some crafty writing and production—it was the emergence of one of the greats. Right from the start it was obvious that nobody was better, nobody was on his level.

During the promotion and marketing of the first album, I got to know Kanye more and I came to understand his vision for both himself and his music with greater clarity. The first album was a hit without me, but going forward, I got a chance to work closely with him—his talent was obvious, and I wanted to do everything in my power to support it. Kanye West was a brand-new artist at that time, and with the company in transition, I didn’t want his album to get lost in the cracks. I spent time with Kanye and made sure that the marketing team stayed involved, always preaching to them that Kanye West was the greatest artist signed to the company—do not fuck this up. Whatever he wants, give it to him. Those were my instructions. If I did anything for Kanye West’s career, it was more when he wasn’t in the room.

Honestly, much as I did with Jay Z, all I did was learn from Kanye. I listened to him, I talked to him, I tried to give him any information I could, but in truth, there wasn’t much that he needed from me when it came to the actual music. He always had a clear sense of where he wanted to go and he looked for talent that would help him get there. Kanye used multiple producers throughout the time that I worked with him, and although he was the primary producer, he used people like DJ Toomp, Mike Dean, Jon Brion, No ID, and Jeff Bhasker—a guy who I thought was one of the great producers, although his name isn’t particularly well known.

Riding with Kanye after his performance at Abbey Road, London

What made Kanye unique, though, was not the diverse list of producers that he worked with, but how willing he was to go beyond the limits of his own knowledge. When an artist is a producer and a performer and they’re in the moment of their success, in the eye of the storm, so to speak, they don’t usually look around for help. They don’t look around for other producers, especially producers whose talents vary so widely from their own. Often they tend to get caught up in their own work instead of asking to hear what someone else thinks. Kanye West may have a public persona of being a very self-focused guy, but the truth about him is that Kanye is always searching for musical growth, always looking for new ideas.

When he makes records, for example, Kanye will have many people come in and out of the room to contribute ideas. His sessions are always crowded, as he surrounds himself with creative people and pulls from these people, feeding off them. He wants to know their opinions and stays open-minded, collaborative. He edits or curates those ideas for his final records. The reason his music grows from record to record is because he allows the influence of other music people into the room. He doesn’t live in a bubble, he doesn’t write in a bubble, and he doesn’t make his records in a bubble.

And then there’s the actual energy he devotes—the man-hours that Kanye West puts into his music are probably unmatched. He is like Steely Dan that way, the pursuit of sonic perfection. He is always searching for a better beat, a better-sounding keyboard, a better lyric, a better chorus to the song. He makes three or four choruses to almost every song. He works at it. It’s always a sound that determines when he’s finished, because Kanye’s sole interest lies in getting it right. I’ve heard different incarnations or iterations of his albums. They sound radically different from the time they start to the time they finish. The early demo tapes sound nothing like the finished product.

The first three albums represented his journey: The College Dropout, Late Registration, and Graduation. The next album in the progression was supposed to be Good Ass Job, but that never got made. Instead Kanye forged ahead into new directions and switched to 808s & Heartbreak, drawing from his personal experience and the changes he was going through as a man. He started to sing and used autotune and other effects, he was making melodies—it wasn’t traditional rap anymore. Sadly, his mom had passed away way too soon, and he put his heavy heart in his music. Our mothers had become friendly—I could understand his pain.

When I went to A&M Studios and sat in the control room and listened to some of the early tracks on 808s & Heartbreak, I couldn’t believe he had come up with such an unpredictable album, and I was excited by his artistic growth and command. I gave him a speech.

“What you’ve done here is you’ve not only changed the course of Kanye, but you’ve also changed the course of music by doing this record,” I said, “and you’re going to see that you’re no longer bound by the rules of hip-hop. You’re now saying that you’re going to take matters into your own hands and you’re now going to do what you want to do creatively, and this album—I don’t know if this is going to be thought of as your biggest album or your most important album, but I tell you what—for my taste, this is the album that defines you as a genius, because you’re now doing what you do.”

I paused for a moment, because I hadn’t planned to launch into a monologue, but I knew that I wanted him to understand how special this was. I’d come to see myself as a protector and an advocate for Kanye, an incubator for his talent. “This isn’t resembling what anyone else does. You’ve let go of all the rules, you’ve thrown away the crutches, and you’re really walking on your own—and you’re walking tall, my friend.”

His response to all my compliments was a simple “Thank you.” No proclamations about being the greatest or entitlement—he didn’t act like my words were just stating the obvious. Despite how he’s viewed by the public, there’s a lot that people don’t understand about him. I knew Kanye’s mother, and he was raised well. The truth is, beneath the persona that Kanye projects, there is a sweet, insecure artist who is eager to prove that he works hard at being great. He’s a student of design, and with that comes a meticulous, exacting nature that leads him to believe fully in the art he’s creating, sometimes to a fault.

After his very public gaffe with Taylor Swift on the MTV Video Music Awards in 2009, Kanye went away, worked at a clothing design firm in Milan, and slipped out of the public eye. He had been gone quite a while when his manager called and said Kanye wanted me to meet with him. I drove in from the Hamptons on a Saturday night to a Manhattan recording studio to see Kanye. He was there with his girlfriend and he was a little bit sad. I could tell he was still embarrassed by the Taylor Swift incident. I think it affected his confidence, because that night he was simply looking for approval. He played me some tracks he had been working on—“Lost in the World,” “Runaway,” and “Power.”

I always find it great when you can hear in the music the change that an artist is going through, and this is something that can make an ordinary pop song into a lasting work of art. With true artists, you can hear when they’re going through a life change. That album, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, was a reflection of him going through a darker period—the Taylor Swift moment, the loss of his mother, probably some more personal things—but you could hear that he’d changed to a different person and he had a different message with a little less humor and a little more anger.

If you listen to “Stronger”—his big pop hit from Graduation, his third album—it was a sort of European underground thing that sampled Daft Punk. But “Power” sounded tribal with the drums and the chants, like he was getting more in touch with the black man that he is, as opposed to “Stronger,” which was the pop star that he aspired to be.

Throughout all his records I could hear these changes, but that day in the studio, as I sat there listening to tracks that would become the cornerstone of My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, was a special moment for me. When I heard those tracks, I knew that this next album was going to be his masterpiece. That’s not to say that he won’t create more than one masterpiece, but that album went beyond everything he’d done until that point.

More than almost any artist I’d ever worked with, with the possible exception of Outkast, I’d been able to watch him change as a person with every record, reinventing everything and yet somehow staying true to his vision and himself, that person who’d greeted me at the Grammys all those years earlier. Regardless of commercial success, seeing an artist I’d believed in achieve that level of personal growth through his music felt rewarding in a way that I’d experienced only a handful of times in my career. It wasn’t about hit singles, or even just about art—though both of those were involved. Instead, it was about evolution, helping an artist come into his own while simultaneously achieving commercial success.

Working with Kanye allowed me to use the lessons of Jay Z—letting him go and simply lending my encouragement—but knowing when to step in and direct an artist’s development was another important skill for me to learn: when to leave my guys alone and when to watch over their shoulders. I never wanted to undermine or criticize the best work of my staff, but I liked to think that my getting involved in the process could be helpful, even inspiring. I was named as executive producer on a couple of his albums—I took my name off 808s & Heartbreak because I didn’t feel I deserved the credit. I was the head of the label and it was a gratuitous credit. I picked singles, made suggestions for music videos. I gave guidance, I gave support, and I marketed him, but for the most part what I did with Kanye was enjoy him. He had his vision, and I recognized that my job was not to interfere but to sit back and help that vision become fully realized.

To me, there’s Prince and Kanye. They are the most creative artists of all time. Kanye is the equivalent of Prince in a different time and space, in a different era of music where the values have changed. Kanye may not be the performer Prince is, but he is equally important. Rap success lives in other places than pop successes, certain cool kids who pride themselves on not being commercial, who want to be the first to discover the hip new thing. Kanye speaks to those people as much as he does to the pop charts. They are an important part of his audience. His success isn’t defined by the charts.

That sense of contributing to a larger cultural conversation was something that I’d been chasing my whole career, and finally, as I hit my stride at Def Jam, I began to feel it. Throughout my career, I usually stayed focused on my own music. While I was generally aware of what was going on in the music world beyond my walls, I always tried not to get caught up in what other people were doing, so that it wouldn’t taint my ears or my efforts with my artists.

Still, there had always been moments within culture that couldn’t be held back. Whether it was the first time I heard Sugar Hill Gang and understood what rap music was, or when I heard the amazing influence that Prince’s sound had on everyone around him, there were always these moments when it felt like the epicenter of culture was shifting a bit, and if you looked at things in just the right way, you could watch that transformation taking place.

That was the case for me in the early ’90s when Dr. Dre released The Chronic and unleashed West Coast rap on the world. I spent days in the studio trying—and failing—to duplicate the drum sound he got on that record. As different as that was from what I was doing at LaFace, it was impossible for me not to take notice, to feel the gravitational pull suddenly coming from the west. A few years later, after my friendship with P. Diddy helped him get Bad Boy off the ground, I felt the pendulum swing once again, only this time it was back east, as every kid was dressing like him and his brand of hip-hop was emblazoned across every magazine, every music video. The shift was palpable and it was real.

But while I’d been watching these trends ebb and flow for years, I’d never actually felt at the center of them myself—never, that is, until Island Def Jam. With artists like Jay Z, Kanye, and Rihanna, I felt for the first time that what I was working on was truly cultural. We were changing the kinds of sounds that got made, the way people thought about the barriers between hip-hop, R&B, and pop. Once again, the epicenter of music had shifted, and I felt proud to watch it in rotation from my seat at the middle.

After all our long, philosophical discussions about music, Jay Z could tell what I was thinking often before I said anything. He had listened to me well, and, it turned out, had absorbed lessons from me, at the same time that I had been learning from him. And when it came to the success of his next record, I had more to do with it than I first realized. The problem was that the success went to another label.

Although he left Def Jam as president in January 2008, Jay Z still owed us another album on his contract. The album was called Blueprint 3, the sequel to The Blueprint 2, his widely acclaimed but not as popular follow-up to his landmark 2001 album The Blueprint. When he felt he was finished with Blueprint 3, he invited me to the studio to listen. I sat at the console and he played the record for me. I told him I loved it and asked him to play it again, sitting there grooving and jamming.

The next day Jay called me at the office. “You didn’t like it,” he said.

“Of course I liked it,” I said. “What do you mean I didn’t like it?”

“No,” he said. “I know you and I know you didn’t like it.”

“Maybe I didn’t hear the big single that I was looking for,” I said.

Jay was right. Although I would never second-guess an artist of his stature and intelligence, we had already done the art piece with American Gangster, and I was looking for the big one. “I was listening in the studio,” I said. “Sometimes I hear better outside of the studio.”

I know my speakers in the office and my car. Sometimes I may hear music a little bit more objectively in my own space, but I was backpedaling and Jay knew it.

“I hear you,” he said, “but I know what I know.”

While he was disappointed by my response, I think he also saw an opportunity to own his future. He stopped recording and decided he wanted off the label. I understood, but on a personal level I was incredibly dismayed; after all we’d been able to accomplish together, to part ways like this wasn’t what I wanted. He was the biggest artist on Def Jam, and I hated to lose him. He went to see Doug Morris and negotiated a deal to buy the album back from the label, something that rarely happens.

After he bought the album back, he went into the studio, reinvigorated now that he had more at stake, more to prove. We’d never spoken about whether he agreed about the need for a big hit single, but my words must have resonated because he came up with two monster hits from his new sessions. One was “Run This Town,” with Rihanna and Kanye West. The other one was “Empire State of Mind,” with Alicia Keys, which became his first number one and a song that went on to become the unofficial anthem of the city of New York. The album was a great big juicy home run.

After the record came out and was a big hit, I reached him on the phone. “You nailed it, didn’t you?” I said.

He knew he did. “Oooh, yes, I nailed it,” he said.

Happy as I was for him, I felt a bit let down—that album was the one that got away. In the end, it was my work as an executive, and honestly, my indifference to the early version of the album, that inspired him to come up with the biggest single of his career. I put a lot of man-hours into coaching, and, in my own way, I pushed him. In pushing him to be better, I also pushed him away. After being so in sync for years and coming to such a clear understanding of what drove us professionally and personally, I think he felt that, for the first time, I wasn’t on the same page.

That Christmas, I went to St. Barts. Jay and Beyoncé ended up staying there at the same time, and one night, he called. “Hey man. I’m in your neck of the woods,” he said. “What are you doing tonight?”

Erica and I joined Jay and Beyoncé at a restaurant for dessert. We adjourned to our house so Jay and I could smoke cigars. Jay knew Usher was on the island so we called him and Usher came over. We sat around a table in the warm evening breeze drinking, talking, smoking a little weed, laughing, and having a good time.

Beyoncé just had a smash with “Single Ladies.” Both she and Jay-Z were on top of the world. They both had the biggest hits of their career. Jay turned to Usher.

“You know, I’m a little bit disappointed in you,” he said.

“Why?” said Usher.

“Because you are one of our greats,” Jay said. “You are supposed to be right now where Beyoncé and I are. Why isn’t that happening?”

Usher shrugged. “I don’t have my guy,” he said.

“Who’s that?” asked Jay.

“LA,” said Usher.

“What do you mean you don’t have him?” asked Jay Z. “He’s sitting right here. He will do anything you want. LA is the reason why my album was so big. I don’t know him nearly as well as you do, so if he can help me, he can help you.”

We sat there until seven in the morning. By then I was so drunk and high, I crashed. I left Jay Z, Usher, Beyoncé, and Erica at the table. The next day Jay called to say he was sorry for overstaying his welcome. I told him there was no such thing, and I was sorry for abandoning everyone. They left at eight thirty in the morning, but it had been a great night.

Jay Z is not the kind of guy to do all the political acknowledgments, thanking this guy and that guy at the label after he’s won awards. The truth is that none of us deserve the credit. But in the dark of the Caribbean night, without even speaking to me, he gave me all the acknowledgment I needed. For all I learned from Jay, I guess I also taught him something, too.