19

HERE COMES THE JUDGE

The morning I woke up for my first day at The X Factor in March 2011, I went to the gym, got a facial, put on my Tom Ford suit, and rode down to CBS Television City. I pulled up to a huge crowd of cheering kids, waving signs for Simon and The X Factor. They didn’t know who I was, but they were cheering for Simon’s show. I knew he was a big deal, but I hadn’t seen this firsthand. My first impression of him in the hotel hallway years earlier turned out to be completely accurate. He’s a star.

Simon Cowell and the British impresario Simon Fuller had reinvented the TV talent show, and American Idol had changed the music scene landscape dramatically in the twenty-first century. What they started in England, they took to a global scale, and they broke radio’s stranglehold on the record business. As record executives, we were often at the mercy of radio. If I made a record and the radio programmers decided it was not a hit, that artist never saw the light of day. The two Simons understood that not all music fit on the radio, and that television could make stars, too. They built a platform that could keep artists on television in front of an audience for long enough to catch on, regardless of radio. Simon had started The X Factor in England in 2004. The immensely successful boy band One Direction came off the show. People in the United States watched the British program online. Simon had imported one of his judges from the UK edition, a pretty dance artist named Cheryl Cole, to be a third judge on the US show.

Going in, I assumed that everything about this world would be different from being a record exec with one exception: how I discovered talent. Because I’d been finding stars for twenty years, I’d built a lot of confidence in my instincts, and I didn’t doubt that I’d be able to re-create that skill on camera. What I didn’t realize at the start, but learned very quickly, was that the kind of talent that would audition for a TV talent show was much different from the kind of talent that I was used to seeing—there was a reason these voices were walking into a soundstage and not my office. Further complicating things was that the actual art of discovering someone on a show also proved to be entirely different; as I came to see, the skills that had made me good at making hit records were not the same as those that would make me a good judge on a TV competition show.

I got out of my car, did a couple of red-carpet interviews, and went inside to the large dressing room shared by all three judges. Benny Medina came with me to keep me company. It would have been a very lonely experience without Benny, going to work by myself, not being the boss for the first time in twenty years. To produce a TV show takes a cast of hundreds. I was a little overwhelmed by the size of the enterprise and the massive investment it represented.

I was the first to arrive, and as I sat in the large green room, I had the strange realization that, for the first time, I was the talent. I was not in control of the schedule—my only job was to sit and wait until they were ready for me. When Cheryl Cole arrived, I introduced myself and we chatted briefly, but she was a bit reserved. She went off into her corner. A few minutes later, in walked Paula Abdul. I had heard they were trying to make a deal with her, and they had closed it only the night before the taping. That was an instant relief—somebody I knew. Other than Benny, I didn’t know a soul. I didn’t know the camera people, I didn’t know the makeup artists, I didn’t know the hairstylists, I didn’t know the guy who went to get coffee, I didn’t know anybody. I hadn’t seen Paula in years—our Pebbles-era drama had been forgotten long ago—but we gave each other a big hug, both happy to see each other. She went to her makeup mirror to prep.

About an hour later, Simon walked in. Everybody in the room stood up. Caesar had arrived. This wasn’t the Simon I knew. This was a new Simon. This was Simon the king, the media star, the mogul, the multimillionaire. He seemed twenty-five feet tall with an aura of power and authority surrounding every step.

“Okay, kids, are you ready?” he said. “It’s time for the show to start. Let’s go.”

Ready? We had been given no instructions, no script, no idea of even how the show ran. No conversations, no “you do this, you do that”—we were simply going to start and figure it out as we went.

“This is what we’ll do,” Simon said. “We’ll go out and we’ll introduce ourselves. I’ll go first, then I will introduce Cheryl and pass the mic to her, she’ll talk for a second, then, Cheryl, you’ll introduce Paula. Paula will talk and hand the mic to you, LA, and then you talk for a second. That’s it.”

That was all the stage direction we would receive. We walked out to a jam-packed, loud, screaming audience. I wasn’t sure what to think. I hadn’t experienced the adrenaline rush of being onstage since my days in the Deele. We did exactly what Simon told us to do. Simon introduced himself. They went absolutely wild. Paula introduced herself, and they went wild again. Cheryl introduced herself and they made a little noise. I introduced myself and they politely clapped.

Looking out at the audience, I found it hard to imagine how the next several months were going to go. We would spend the next two months on the road filming the first show and auditioning the nation. We collected candidates from two cattle call free-for-alls in Los Angeles before heading out on a six-city tour and selecting performers for a boot camp. At the X Factor boot camp, each judge would be assigned eight performers to coach, cutting them down to a final four before the end of the first show of the season. Each judge supervised one of the four categories of teams; the Young Boys, the Young Girls, the Overs (older than young), and Groups. The ultimate winner would receive $5 million.

We adjourned to the judges’ table, the cameras started rolling, and they brought on the first talent. Simon bantered with the guy, he sang, and Simon turned to our table.

“Okay, let’s see what the judges say,” he said. “LA, what do you think?”

It was my first time. I sputtered—“Well, I thought you were good” or something—and another judge jumped in. Soon they were talking over each other. It was all very clumsy. For the first time, the thought occurred to me that, wait a minute, Simon did American Idol and X Factor in England, Paula Abdul was an American Idol judge for years, and Cheryl Cole came from X Factor in the UK. I was the only one who didn’t know what he was doing.

We auditioned talent for two hours before taking a break. Backstage, Simon was noticeably upset, but I had no idea what was wrong and figured it must be me. I’d taken on this job, changed my life, and now I was a complete failure. Nobody came up and talked to me, and that made me even more uncomfortable. Simon and his production team were holding a meeting in the corner of the room, and, damn, I was not used to being on the outside. I was used to sitting at that table.

Simon broke up his meeting and came over to talk with us. This time he had more specific instructions, a little form, a little choreography. We went back out, and in a much more orderly manner, we auditioned talent for another six hours. After that, we were steered into the press tent and sat for interviews for another two hours. It was eleven o’clock at night before we were done. It all started again the next day.

I soon learned that the biggest difference between auditions as a record executive and auditions on television is that, as a record executive, I never had to tell people what I thought or why I thought it. Working for a label, I would watch the audition and I would rock my head, but it would throw you off. You never knew whether I was loving it or not. Often I was a little ambiguous on purpose. On television, there could be none of that ambiguity—I had to explain myself in a way that I never had to before. I had to learn how to talk and I had to tell everybody my thought process every step of the way. Every audition, all the way down to the final episode of the final show, it all came down to my opinion. You couldn’t say the same thing over and over. I had to develop a vocabulary, a style, a speech pattern. I had to put hooks in how I spoke and I had to build tension and not give it away too quickly, a yes or a no, stay or go home.

All the time I was judging talent, my mind was buzzing. Instead of focusing intently and developing a vision for the artist in front of me as I always had during auditions, I was concerned with my personal stagecraft and listening to myself, so that I knew exactly what I was going to say. At the same time, questions were scattering around my brain about my role on the show. What did I need to do? Should I try to be funny? Should I try to be smart? I needed to figure out my mojo. Who was the character I was creating? What was the personality? Who was I supposed to be? Was I LA the record executive? Was I supposed to be a comedian? Was I supposed to be the talent expert? Who was my character?

I had thought about all this, particularly my character, quite a bit before I went back for the second day. I’d spent years helping others create their own stage personas and now I was trying to understand my own. I picked up a lot listening to Paula and Simon. I started to figure out what I was supposed to do, even though I wasn’t getting much guidance.

After a couple of takes, Simon looked over at me and he winked. “That was really good, LA,” he said. A couple of producers gave me tips. “Don’t be so quick to say yes and no,” one producer said. “We need you to give it a little pause. We need to create some jeopardy here. We don’t want you to give away your answer quickly. This is television.”

Much as I’d always been eager to learn in my old job, I found every suggestion helpful now. Before we started our six-city tour for auditions, the producers caught up with me while I was with my family—finally giving me some feedback about my character.

“LA, we just wanted to have a word with you about wardrobe,” said one producer, “because the first day you wore your suit and you looked like an executive. The second day, you wore sweaters and were a little bit more casual. We want you to keep your executive profile. We don’t want you to be casual. We want you to be the talent expert, the seasoned executive. That’s the character we want you to play. Otherwise, you’re doing really good and we’ll see you in Chicago.”

This was nothing I didn’t know already, except for the part about the necktie, and I never mind dressing up.

After the second day in Chicago, one of the producers took Simon, Paula, and me aside to shoot some YouTube promos. I wondered about Cheryl, but didn’t say anything. After we finished, Simon asked me what I thought about Cheryl. I told him I thought she was good. Then he asked me about one of the cohosts, Nicole Scherzinger, a singer I knew who recorded for Interscope Records. “Do you think you’d like Nicole better next to you or would you like Cheryl next to you?” he said.

“I like Nicole,” I said.

“Okay, then it’s done,” he said. “We’re sending Cheryl home. Nicole’s going to be the judge.”

What? Did I just get somebody fired? Doubtful. They clearly had already made their decision, but he wanted to run it by me. At the next city, sitting next to me was Nicole. While we were on the tour, all of us became friends. At night we would hang out after the show and maybe have a drink at the hotel bar.

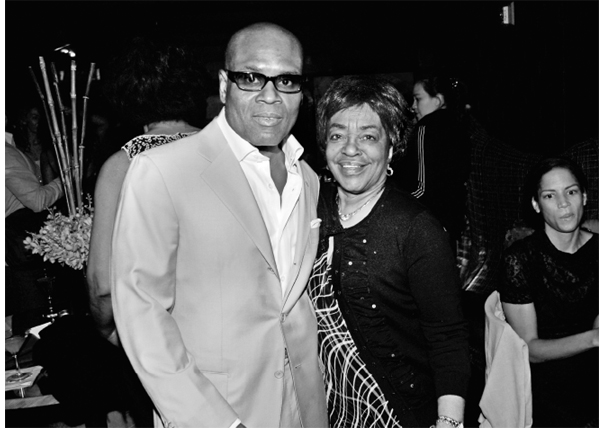

The last day on the road shooting the show, I was woken early in the morning by a phone call from Erica telling me that my mom had died from a heart attack. She had had previous episodes, surgeries, so it was not altogether unexpected, but damn, it hit me hard. I didn’t say a word to anyone. I struggled through the taping, went home to Erica, and flew to Cincinnati to take care of my mother. I told Simon only after I left.

With Mom at my fiftieth birthday celebration, New York

My mother was where I got my people sense. She had unerring insights into people and she was always proud of my accomplishments—my gold records covered the walls in her home—but she was also always straightforward with me if she didn’t like something, which was often the case. She had gotten to know all my children; traveled the world to Japan, China, South Africa; she could shop for what she wanted to shop for. I didn’t visit her in Cincinnati as often as I would have liked, although she was a regular presence at our family functions in Atlanta and New York, and when I did go to see her, I always took a private plane so I could leave when I wanted, worried in the back of my mind that somehow I would get stuck in Cincinnati. I managed to pull myself together and get back with my work, but she never leaves my thoughts. To this day, I can’t bring myself to sell her house.

On the show, I tried to regain my focus. My character began to emerge from my banter with Simon. We became bookends. Simon was on one end, me on the other. Simon was the famous TV executive who had done this for many years and been hugely successful. I was the record executive who had actually discovered famous stars, so I played the professional expert. We would pick on each other. He liked to team up on the girls. Nothing was scripted. I wore cool glasses and expensive suits. When I started The X Factor, Justin Bieber was one of the world’s biggest stars, and we definitely used his name and his association with me to promote The X Factor. The same was true for Rihanna, whose appearance with me as a celebrity mentor with my team was one of the highlights of the first season.

Simon and I developed a genuine chemistry between all the judges. Sometimes there would be backstage wheeling and dealing, such as when you needed to lobby the other judges if you wanted one of your acts to win.

“LA, you’re going to have to help me,” Simon might say. “I really want to keep the girls.”

And we’d bullshit each other. “Okay. No problem, Simon,” I’d say. “I’ll keep the girls.” Get out in front of the cameras and turn on him. “Girls, I’m going to have to send you home.” It was fun.

When I was on break with my family, Simon called from London. “LA, I’ve been sitting in the edit for the past two weeks,” he said, “and I have to tell you, you are fantastic. You are a complete star on this show. You’re going to be the surprise. As I look at the whole thing, you’re the breakout.”

This made me happy. I went through the entire process never knowing, never looking at tape or photographs. I just did the work. I didn’t know how I looked or sounded. Now I was ready for the season.

For the season opener, Simon threw a red-carpet premiere at the Chinese Theater in Hollywood. I was used to music business press, but TV press was a whole different animal. There was a mob, from networks to bloggers. Simon made us sign up for social media (which is why I still have 1.3 million Twitter followers). They did a great job at building up anticipation for the show. I still hadn’t seen anything, and when the lights went down, I saw it for the first time.

The edits were beautiful. I had gone through those auditions in kind of a daze, but the way they cut it together turned out really well. The crowd in the theater was laughing and exploding into applause. “I’ll be damned—I can change my life,” I thought. “I’m a television personality.”

When the show aired the next night, fourteen million people tuned in. The only problem with that was that Simon had crowed to the press that he would have twenty million people watching The X Factor. The press jumped all over him and trumpeted the show as a failure because it didn’t live up to Simon’s exalted expectations. Anytime you can get fourteen million people to do something, it is not a failure, but the press didn’t see it that way. “X Factor doesn’t have the X factor” was the way they saw it.

In spite of the response, I was having a ball, hanging out with Paula, Nicole, and Simon. Some of the crew were becoming buddies and I looked forward to seeing them every day. I loved the whole ritual of getting ready for the show, going to the gym in the morning, working out really hard, deciding what to wear, listening to music to get pumped up and to go on the stage and do the show. A couple of times, I rented out restaurants and threw big dinner parties while we watched the broadcast on large-screen televisions. After the slickly produced season premiere, the show went live every week and each judge guided his or her final four through the season, gave them songs, and coached them.

When I went out in public after The X Factor started running, my life changed completely. All of a sudden, everybody knew who I was. The first time I noticed was when I went to an art exhibit at my children’s school in Brooklyn, and every kid in the place came running over to me. The whole school crowded around, all the grades: “Hey LA, can I have an autograph? How’s Simon? How’s Paula?” My kids loved it. Everybody wanted to take a photograph and my kids jumped into the pictures with me. The little ones were the best. Our audience demographics skewed either very old or very young. The people in between didn’t pay us any attention. At the Starbucks or Footlocker, it was always the young kids that got the most excited.

This was my new life. Finally, after all these years, I was receiving recognition for myself, not for something I did for someone else. For five minutes, I really loved it.

During the summer leading up to the show’s premiere, I’d closed my deal with Sony to start my new post as the chairman-CEO of Epic Records. I was still on the road and doing these long days with The X Factor, but as of July, I was also running a record label. In August, I had the month off the TV show to work at the label, but in September I had to go back to the West Coast and start shooting weekly episodes. It quickly became clear that I had no idea how I was going to do both jobs.

For starters, I needed to build a staff. Only one person came over with me from Island Def Jam because Lucian had been so angry over my departure that he threw large bonuses at my executives to stay, so I was forced to work with executives I didn’t know. But even more dire than the staffing situation was the fact that I’d been hired to breathe new life into Epic. Epic was the ugly stepchild of the company’s prestigious main label, Columbia Records, and had long been in decline since the glory days of Sly and the Family Stone and Michael Jackson’s Thriller. The label had no roster to speak of and it was at an all-time low in the label’s long history. This would require a complete rebuilding effort, a tough task under normal circumstances, but with the show going on, it was much more complicated than I’d ever envisioned.

The show was taped on the West Coast and I worked out of the Epic Records office during the day, but I was going through the motions running the record company while my mind was completely absorbed by The X Factor. Being a record executive is one of the most labor-intensive jobs in entertainment. It’s the staff, the roster, auditions, mixes, marketing meetings, hiring. I could barely take phone calls during the day. Although I had become something of a record industry brand, so to speak, I wasn’t attracting the executive talent I needed, largely because I was now running a label that wasn’t having much success.

Making both of my jobs harder was the fact that finding talent for Epic and finding talent for the show were two very different things. The deeper in we got, the more I understood the difference between talent on a show and at a record company audition. On a TV show audition, something is wrong already because you’re there—it’s pretty much a foregone conclusion that you’re not going to make it in music. Why else would you be trying out for a TV show?

In our shop talk backstage, the judges always said that Prince would have never auditioned for a show like this. Or Bono. You don’t get Jimi Hendrix. You don’t get Led Zeppelin on a show like this. You don’t get Diana Ross, Drake, Lady Gaga, or Kanye West. You get talent who are okay with people telling them what to sing, what to wear, how to dance, when to dance. Nobody could have ever told Madonna what to wear or made Bob Marley sing “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree.” I’d always thrived around artists like Pink or Avril or Mariah, who, even though they wanted to make pop music, all had their own visions for the kind of artist they wanted to be. They were creatively open-minded but with their own strong point of view. On The X-Factor there was little of that vision from the contestants themselves.

Still, working with the contestants on my team had plenty of fun moments. On the show, I sat on my back deck of my Hamptons place next to Rihanna to pick my final four. They auditioned for us and then came back, one at a time, to learn their fate. You would have to build up to it—You were really talented, you were much better in the auditions the first time I saw you, this time you weren’t quite as good, you weren’t as convincing; I’m not certain that you’re a star, but I love your dedication, I love your voice tone, and this is a very tough decision to make. . . . Big pause. “You’re in my final four.”

Of course, they always went crazy. But if you were sending someone home, they would occasionally get a little angry and security would have to escort them away.

One of my favorites was Astro, a fourteen-year-old rapper with an attitude. He stood out right away at boot camp when he refused to sing, dance, or do any ensemble pieces. “I’m a rapper,” he said.

A rebel like that might be the last thing you’d think you would find on a TV show. I loved the kid. Finding material for Marcus Canty, an R&B singer who could really sing, was easy, but getting songs for Astro was always difficult. Sometimes clearing a song with music publishers could be an issue. You might want to sing “When Doves Cry,” but Prince would never allow it. I called Eminem’s manager to see if I could land “Lose Yourself” for Astro from him. It turned out Eminem watched the show and liked the kid, so we could clear the song. I was able to get Michael Jackson’s “Black and White” for him on an all-Michael Jackson show. We had to rewrite the chorus for him, but we nailed it.

Chris Rene was a trash collector and a drug addict in early recovery from Santa Cruz, California. He turned the place out with an original song that the world had never heard, “Young Homie,” and rocked that crowd.

Out of the first season, I signed Chris Rene, and we did an album with him, but “Young Homie” didn’t turn out to be a hit. We also signed Marcus Canty, the soul singer who could sing his ass off, and he didn’t work for us either. I signed the winner of the first season, the girl who took home the $5 million, Melanie Amaro. She came to the office exactly one time and she had about as much drive as a broke-down car. She called me once around eleven o’clock at night to ask if she could get a discount at the Sony store.

Despite enjoying my artists on the show, by the time we were halfway through the first season, I couldn’t ignore the reality that Epic Records had become an increasingly serious project for me. As I built the label, I was hiring executives, and they had to come to the set to hold our meetings. By the end of the first season, my dressing room was filled with Epic executives. I grew impatient to spend time with my label.

As I struggled to balance both the show and the job, the two became entangled in a way that undermined my efforts at Epic. For one thing, how I listened and evaluated talent changed. For my entire career, when I’d discovered talent, there were always aspects about the performers that I liked that I couldn’t articulate. Seeing potential in an artist isn’t always something that you can easily put into clear words. However, as I was forced to do that on the show, I found myself gravitating toward the artists and suggestions that were safer, easier to explain, that had the kind of potential that can be communicated in a fifteen-second sound bite. My feedback became more superficial because it’s what the medium demanded.

But more than that, I didn’t focus on the same things that I once did, because what made for good TV wasn’t necessarily what made for good music. Sure, part of that was because the caliber of artists we had on The X Factor was not what I was used to, but the other, and arguably bigger, part came from the fact that the goals of the show were not consistent with my own standards. Good TV is fueled by conflict—between the judges, between the artists, between the judges and the artists. Almost by definition, the process of competitive auditions lends itself toward this kind of drama, but it doesn’t necessarily produce the artists most capable of making a hit record. It’s a very specific kind of talent and mind-set, one that often rewards a shallower approach.

Initially, I thought I could manage to make a distinction between TV talent and hit record talent, but over time, it started to cloud my judgment. By the end of the first season, it became apparent to me that working on The X Factor had taken me further away from the music rather than closer to it. By joining the show, I’d taken a step away from my passion—the first time that had happened in my career.

As that reality hit home, I had some dark private moments, wondering what I was doing, where my friends were. I found myself fixating on what my artists were thinking and whether or not people like Jay Z or Kanye approved of what I’d done. I worried that Rihanna thought I’d lost my mind, and Mariah assumed I’d abandoned her. Perhaps Jennifer Lopez was wondering why I was trying to be a star, and Justin Bieber figured I didn’t like him anymore. I tend to overthink things, but I couldn’t shake these feelings of being judged by people whose opinions I respected.

And then there was the stardom itself. Of course that had been part of the excitement at the beginning, but the more time I spent in the spotlight, the more I realized that all the clichés about the trappings of fame were clichés for a reason. It didn’t take long for the appeal of the notoriety to wear off. When it did wear off, all that was left was a painful irony: while I was finally getting the credit I’d long sought for my accomplishments, I’d been forced to move away from my passion for music to make that happen.

In spite of all these frustrations, I really did enjoy that first season of The X Factor. In many ways it was an experience that I needed to orient me toward the future. The camaraderie among Simon, Nicole, Paula, and myself was real, and taking on a new life doing television for a year turned out to be the break I needed between Island Def Jam and Epic Records. I’d been on the same grind for so many years and had gone through a lot emotionally. I needed to regain my energy, remember why I’d gotten started in this business to begin with.

With that out of my system following the first season, I was ready to sit down and focus full-time on Epic. I had no desire to stop, no anticipation to stop. I didn’t want to stop. The show had given me focus by reminding me what my true passion was, and going back to TV would be an unwelcome interruption. The only problem was, I’d already committed to doing a second season.

I had no desire whatsoever to do the second season. Zero. In fact, I almost didn’t do it. I waited until the very last day, the final day that the auditions were supposed to start. I spoke to Doug Morris, who told me it was too late to back out.

“But now that I’ve gotten Epic started,” I said, “this is what I want to do. I’m a record man.”

At the Fox upfronts with the X Factor season 2 cast: Demi Lovato, Britney Spears, and Simon Cowell, Central Park, New York (©ImageCollect.com/Globe Photos)

“I told you that before the first season and you went ahead and did it,” he said. “Now you’ve got to finish it.”

I went through the second season, but with a bit of an attitude. The thrill was gone. While I tried to do a good job, I knew the second season would be my last. The second season was a different panel. Simon and I were back, but with us were Demi Lovato and Britney Spears. I became fond of Demi, but I could never get particularly close to Britney, even though she was seated right next to me. I was used to having fun, silly Nicole Scherzinger beside me. Britney was an introvert and not as communicative and, frankly, not a lot of fun. I worried about my stress showing on TV; they say a television camera is like an X-ray. I was already tired of the show. I was ready to get back to my real job.

When the producers phoned—I took the call on camera—to tell me I had been given the Overs to coach, I slammed down the phone and walked out of the room. I wanted to quit right there. The old guys? What am I going to do with the Overs? That’s not my thing. I signed Usher at fourteen, Avril at sixteen, Rihanna at seventeen, Justin Bieber at fourteen, TLC at seventeen. I don’t do adults. I simply didn’t have any interest in it. Once I got into it, I did end up having fun with the talent and even won the second season. My contestant, Tate Stevens, was a country artist, and it turned out that I love country music and didn’t even know it. He introduced me to Garth Brooks songs like “The Dance” and “Friends in Low Places” and taught me the difference between country and bluegrass. That was something brand new.

By the end of the second season, all the realizations I’d had after the first season were still staring me in the face—only this time they were amplified. I was embarrassed about my record label and where it stood. I was embarrassed that I’d paraded myself across the television network like a clown. I was embarrassed that I had this desire to be famous or to connect the dots. I was embarrassed by my decisions. I had reduced myself to being unimportant talent, and that made me upset with myself.

The second season had also complicated things for me at home. Being away from home so much, living in Los Angeles while my family lived in New York, had grown stressful on my wife and kids. I didn’t see them enough. I was trying to do my job on television and working hard on the record company, struggling to stay focused. Meanwhile my wife and family were not impressed or happy that I had become a TV star and was living in Hollywood, which added to my stress.

I will say that I was a decent actor. I wouldn’t win an Academy Award, but, looking back, I covered up my tension and unease. But as soon as the camera went off and my adrenaline came down to earth, there was this unhappy soul. Doing live television in front of a live audience will send your heart racing, and I had tough times at night coming down. I found myself trying vigorously to be normal when the truth was that my adrenaline had me floating. I made the mistake of putting a Google Alert on my name and read everything that was written about me. Some things were good and some, they took you to the cleaners. Either way, it was all having a negative effect on me. For the first time, I could feel my lights dimming, like I had lost my grounding, my all-important sense of self. I needed to get my mojo back.

I pulled something of a fast one on my way out. I gave an interview to Shaun Robinson of Access Hollywood and gave her the exclusive on my leaving the show, provided she held the interview until after we taped the last episode. I never told anybody I was leaving. They aired the interview an hour early and the whole time I was taping the last show, Simon was glaring at me. At the first commercial break, Simon wanted to talk.

“What have you done?” he said.

“Simon, I’ve just had enough,” I said. “I did the best I could do for you and I’ll do anything for you, you know I will, but I really just can’t continue.”

“But why the interview? Why didn’t you tell me?”

“Honestly, you want me to tell you why? Because if I had told you, you would have spun it to the press that you fired me. You can’t give a record man control of the media. We’re cut from the same cloth. I beat you to the punch.”