20

EPIC LIFE

Quitting the show gave me room to focus on the label, but just because I had more time, it didn’t mean that everything suddenly ran smoothly or that the hits started rolling in. In fact, at first, things only got worse.

When I came back at the top of the year after my Christmas break and the end of The X Factor, I had to deal with the reality that, for the first time in my life, I was no longer that guy. Epic Records was the smallest of the company’s three labels. Columbia had Beyoncé and Adele, the top artists in the world, and RCA had the biggest roster of stars—people like Justin Timberlake and Alicia Keys, not to mention all my former LaFace performers. At Sony Music’s corporate meetings, I was sitting there with no hits, no roster. I’d never known how that felt and I didn’t like it. I didn’t know how to walk the halls and not be the hottest guy. I didn’t feel the same when I walked into a room. I didn’t know what to say, how to talk, what to wear. I felt empty. It was a psychological adjustment, and a painful one at that.

I’d never been cold in my career, not from LaFace to Arista to Island Def Jam. That ten years of Island Def Jam and Arista meant going to the Grammys every year with nominations in many categories. Now I didn’t have a reason to go to the Grammys, because none of my acts were nominated. I didn’t have a reason to go to the American Music Awards. I didn’t have a reason to go to the Billboard Awards. None of my acts were on the show. I was out of the game.

It didn’t help that I was still struggling to assemble a staff. With the craziness of the show behind me, I looked over the team I’d put together and realized that when I was working on The X Factor I’d made a lot of bad staffing decisions I now had to live with. I’d spent years putting together and fine-tuning a team at Island Def Jam, and I hadn’t invested the same energy in team-building at Epic. I was in a company with people I didn’t know well, with artists that for the most part hadn’t done well. I felt that I was punching beneath my weight class.

The worst part, though, was not the corporate dynamic, it was the fact that I remained under the influence of the shallow when it came to finding hits. Despite being aware of how the show had altered my ear for talent, I found it hard to counter that change. Not only did I sign five acts from The X Factor, I signed other acts that resembled The X Factor acts and had failure after failure after failure with them. The one bright spot was that I signed the girl group Fifth Harmony from the show’s second season and they went on to become the most successful act off of the show, developing into a girl band that I quite like. But beyond them, I signed acts because I thought they had a platform and thought maybe it would work for me. It didn’t. I couldn’t get it right.

My bar had lowered too far. When I’d had success in pop music, it had come from being able to fuse and cross genres—R&B and rock, traditional pop and R&B. I’d never worked with cotton-candy, sugarcoated pop music. Coming from the show, I was trying to duplicate that bubblegum pop, only I couldn’t figure it out. I took it as a challenge, remote as it was from my R&B roots: Okay, I can do sugarcoated cotton candy, too, let me show you.

It took that string of failures to show me that I couldn’t do it. I began to question everything—my taste, my sense for talent. Perhaps those two seasons had taken such a toll on me that the music and the world had passed me by. The pace of the music world is unrelenting, and I considered whether I no longer understood what was hot and what was not. I lost interest in most of the talent, and then I lost confidence in myself.

It took Babyface to set me straight.

Kenny and I never stopped talking and always stayed in touch. When I was at Arista, I had negotiated a deal to get Kenny off Epic Records and executive produced an album with him. That was the beginning of our working together again, and when I left for Island Def Jam, I took him with me. But the truth is I never felt that Kenny and I had completely broken up. I think it’s safe to say Kenny is the guy who knows me better than anyone. He is more like a brother than a best friend, and he has been since the day that he walked out in that studio from singing “Slow Jam” with Midnight Star. We became brothers that day and we’ve been brothers ever since. When we fight, we’re fighting like brothers fight. We might fight one day about something or another, but we will always be brothers.

Not only does Kenny know me as a person, he knows me musically, and what he told me was that I was just going through the motions.

“I know you are living this great life,” he said, “the big apartment on the Upper East Side, the big house in the Hamptons, your kids in private school, drivers, cooks, and nannies. You and your family have this wonderful life and you’re just a guy going through the motions, paying the bills keeping up this life, but it has nothing to do with who you are and your soul.

“That’s not who you are,” Kenny told me.

“You’ve painted yourself into a box,” he said. “It’s not who you are. You like to feel it. You like to feel love. As much as nobody likes to feel pain, you get inspired from feeling pain. You wrote certain songs off the pain you felt. You wrote certain songs off the love you felt. You made certain career decisions and signed certain artists because it spoke to where you were in your life at that moment.”

What I heard Kenny telling me was that as long as I wanted to be safe, my music was going to be safe. He was trying to push me out the door. Babyface was saying there was no point to making soulless music. It doesn’t stand for anything but a number on the pop charts.

“We used to write songs in your living room,” he said. “Now when I come in your living room, it’s so quiet I’m afraid to touch the piano because it’s going to disturb the house, because it’s no longer a music environment. It doesn’t feel friendly. I come in and I can look at your piano, but I can’t play it.”

I knew Kenny was telling me the truth as soon as I heard it. As I’d been trying to diagnose my problems, I’d been focusing on the wrong things. I’d paid attention to whether the problem was me and my ear—whether I’d missed the moment and couldn’t get it back. Instead the reality was I’d gotten caught up in a vision of myself that wasn’t me—like one of my artists trying to force a sound that didn’t come naturally. I was trying to make music that I couldn’t relate to, that I had nothing in common with. When I looked at what those artists and signings had in common, I realized that if something wasn’t coming from my heart, I quickly lost interest in it.

Hearing Kenny’s words drove all that home. I thought back about everything we’d been through and how far it had all come. From my mother’s garage in Cincinnati, to my old house in Atlanta, to my office across the halls at Def Jam. The one thing that all those places had in common was that, in my mind, each one conjured my passion—got me excited about my music. That was the feeling that I needed to re-create. It wasn’t enough to identify that my ear had gone saccharine—knowing that was important, but alone it couldn’t do anything. I had to find the sound, the artist who would give me that spark back.

If you’re a record man, musical taste and direction are the determining factors of your career. This isn’t true if you are a business executive, working in finance or in legal or some operational function at a record company; then taste doesn’t matter. But if you’re a record man, it’s all about your taste. I found out that I was not a TV star. I learned that I was a record man.

I sat there, trading glances between Kenny and the piano sitting in my living room, and still hearing his words beating around my head. I was now clear about what my career was, about who I was as a professional. I didn’t start out to be an executive. I started out as someone who loved and cared for music and artists and tried, sometimes desperately, to make music that I could be proud of. I had to do a lot of deep digging and soul searching to figure out how I got lost—and more important, how to get back on track.

To reconnect with my spiritual and musical roots in both the most broad-reaching and deeply personal ways—as well as reignite the Epic brand—nothing could have been better than a Michael Jackson album, and that was exactly the project I launched.

As with most people in the world, Michael’s death in 2009 had hit me hard. So much of the work he’d done had influenced my own tastes. His album Thriller was the pinnacle of Epic Records’ history—and perhaps all of pop music history—and his absence was still felt years after his death.

I had dinner with executor John Branca in Los Angeles to talk over the possibilities of working with the Jackson estate. I convinced him to let me put together an album of the existing unreleased recordings. They delivered all the music and I sat in my office, unpacking the boxes and listening to every demo that Michael Jackson ever made. It was like being left alone with the crown jewels, and I slowly started to sort through what Michael had left behind. I sat alone late into the night in my office overlooking the Upper East Side skyline and listened, feeling the magic of Michael Jackson engulf me.

Because Michael recorded specifically for albums, there were surprisingly few complete pieces sitting around unreleased. Not only were there not as many as I thought there would be, but my first time listening through them, I could see why they hadn’t been released. Still, I kept listening and listening.

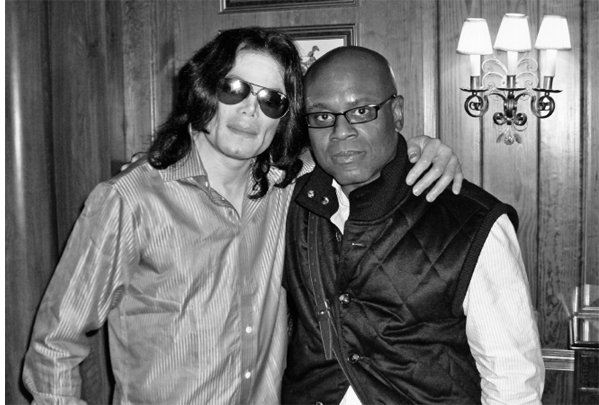

With Michael Jackson at the Dorchester Hotel, London, 2007

A lightbulb went off when I heard a piano demo of songwriter Paul Anka playing and Michael Jackson singing a song called “Love Never Felt So Good.” That one was different, really good, and it had never been finished. It was only a piano and vocal. Now we had something to work with, and that one song sealed the deal for me and made me commit to making an album. I searched through the tapes for all the songs that Michael had sung from top to bottom. A lot of takes were partly finished or only had stacks of background vocals. I found about eighteen and whittled those down to ten, nine by the time I released the album.

Yes, I was, at that point, working with remnants, but remnants from one of the greatest artists who ever lived, and if that doesn’t take your bar up higher, nothing will. Hearing his naked vocals in the studio with all the tracks turned off, hearing just his voice, you could feel his energy and the perfection of his delivery. He was a flawless singer, flawless. He later became known for his dance moves and even some of the craziness that surrounded his life, but at the core of it—back to the very beginning with the Jackson 5—we’re talking about one of the most brilliant singers who ever opened his mouth. That talent never left him. When I got these tapes and I listened to those naked vocals, I realized that this guy was really the greatest and I was back working with the best.

I gave the tapes to Timbaland, who is one of the most incredible producers ever. Timbaland took the tapes, stripped away all of the original music tracks, and built the records around Michael’s vocals. He created the music tracks. It was Timbaland who convinced Justin Timberlake to sing on “Love Never Felt So Good,” which gave the record a boost with contemporary radio, where Michael Jackson is no longer a fixture but Justin Timberlake is.

The whole time, I paid close attention to Timbaland’s work. I spent more time in the studio working on the Michael album than I had in twenty years. I immersed myself for six months. I was in the studio for every mix, day and night, listening intently in the dim light late into the night. I basically kind of took over and I probably even got a little heavy-handed about it, but it was hard to help it—my passion had come back.

When I was searching for a title to the album, I spoke to Babyface.

“This is a Michael album,” he said. “No one titles Michael’s albums. Michael has to title it.”

I wondered what Kenny meant by that, but as I started listening to outtakes of Michael from the This Is It concert movie, I heard Michael talking between songs. “It’s about escapism,” he said. “People want an escape.”

I already had a song called “Xscape” that he wrote and produced with Rodney Jerkins, and now it was my title track and Michael had named the album.

With everything coming together, I had one more, very personal, piece to add. Deep in my own tape vault, where nobody knew it was there, I had “Slave to the Rhythm,” the one song Babyface and I finished with Michael in 1989. We did that music under a private arrangement with Michael and the record company never knew about it. As I pulled that out, dusted it off, and handed it to Timbaland so he could work his magic, I couldn’t ignore the symmetry: I was working to complete a track that Babyface and I had put together almost twenty-five years earlier. Babyface and Michael, working together to bring me back to myself. Kenny and I had always wondered whether this session that we’d worked on all those years ago would see the light of day. Now, sitting there in the studio, with the mixing board in front of me, the song we’d begun more than twenty years before finally finished and jumped from the speakers, I knew it was worth the wait. Satisfied, I stretched my legs out in the engineer’s chair, catching a glimpse of my reflection as it bounced off the darkened studio glass. I knew we had something special, but I wasn’t thinking about any of that—I was too busy having fun.

For the release of the album, we made a groundbreaking holographic Michael Jackson performance of “Slave to the Rhythm” for the Billboard Music Awards, and when it finally dropped, the album sold three million almost as soon as it came out in May 2014.

I was on my way to Japan earlier in the year to preview the album for Sony executives when another act I had signed to Epic blew up. I was sitting on the plane checking iTunes when “Say Something” by A Great Big World hit number one. Ian Axel and Chad Vaccarino were two Brooklyn kids who had studied music business at NYU and released a record on their own that had picked up some steam.

I first heard the band while I was on an equestrian weekend with my family in Miami. My daughter Arianna loves to ride horses. Richard Palmese, a long-standing friend who used to run MCA Records, emailed me a demo and I downloaded the track to my iPod and played it all weekend, debating with Arianna about how good the group was. All my kids, whether they like it or not, work for the label, and I have often relied on Arianna’s opinion, but this weekend I couldn’t help but feel I liked this group a lot better than she did.

Like all my favorite artists, Ian has a distinctive hairdo, his very famous Jewfro, as he calls it. Their voices reminded me of Simon and Garfunkel, not that they had a kind of retro sound, but, without being a copy of that era, they felt as special to me as everything I’d heard back then. They had already tapped into a unique sound all of their own. For me, that was enough. When they came to my office, I didn’t even have them audition for me. For whatever reason, I simply had them play me demos and I listened to their songs. I convinced the band that I would kill for them. I even told them I believed they would be the first act from the new generation of Epic Records to win a Grammy, a boast I later repeated to my staff when I played the group’s music at a meeting. I loved their sound, I loved the way they looked. They had everything I needed. Whatever they would become as performers was yet to be seen, but I was fine with that. We had everything we needed to launch. I had my first something at Epic Records.

We put out their song “This Is a New Year,” and although it was not an out-of-the-park smash, it was a great song to display the band’s talent and enough to set up promotional tours and make them familiar. They did a music video that became a YouTube sensation and was great ground-laying. The next batch of songs they sent me included a number called “Say Something,” a beautiful piano ballad, just their voices and a piano: “Say something, or I’m giving up on you / Say something.” It was just the most beautiful, heartfelt lyric, so sincere, so soulful that it would bring tears to your eyes. It was at that moment that I knew we had something great. I played it for everybody, but I did not release the song as a single right yet.

Then I got lucky. Doug Morris liked to say it is better to be lucky than good, and what happened next had nothing to do with anything I did. The TV show So You Think You Can Dance used a forty-five-second slice of the song in its dance competition. The next day, we sold fifteen thousand units at iTunes. The next day, we sold another fifteen thousand. And the next day. There was no radio play, no music video. The song plays forty-five seconds on a TV show and starts to sell.

But, wait. Christina Aguilera heard the song and asked if she could sing on the record with the guys. She quickly went into the studio with A Great Big World and did the most tamed, beautiful vocal performance that perhaps she’d ever done in her career. She sang on the song with the guys, but she never took over the record. She provided a simple, tasteful complement to the guys. Christina Aguilera is one of the great singers of her generation, and perhaps even underrated in how great she is. You’d be hard-pressed to find someone who’s better than her. Her manager, Irving Azoff, who had always been something of a godfather to me, was kind enough to allow this to happen. A month after the TV show in November 2013, we released the version of the song with Christina Aguilera and A Great Big World, and it starts selling a hundred thousand copies a week. By the time I was on the plane to Japan, the song was on top of iTunes.

I said to myself, Wait a minute, this is actually working. Babyface was right. That was the first moment that I started to find myself again, because this was a song that had a soul. It was a song that had a pulse. It was a song that had real meaning, a song that meant something to my life, to other people’s lives. It wasn’t just an empty, saccharin-filled pop song, but a meaningful ballad so great that Christina Aguilera, who clearly isn’t desperate, who is a big star on The Voice and who has a wonderful career, felt compelled to sing on it. That was the turning point for Epic Records right there.

I started to feel some internal momentum, even if it wasn’t obvious to the industry or the public yet. We began to attract some talented executives. I was listening to all the music that came in, taking every audition that came through the door, still digging for that needle in the haystack, still trying to thread the needle from across the street, still looking for the impossible. That was when I signed the Kongos, an alternative rock band of four brothers who grew up in South Africa and London, but lived in Phoenix. Their father, singer-songwriter John Kongos, had made records in the seventies with Elton John’s producer, and the group was already having great success in South Africa.

Dennis Lavinthal and Lenny Beer of the influential industry tip sheet Hits came to my office, opened up a laptop, and dialed up this song, “Come With Me Now” by the Kongos. It sounded like a smash to me. Things were definitely starting to change.

“I love this band,” I said. “Can I see them?”

“The guys are actually not here,” Dennis said. “They’re in Phoenix. They have another offer from another label that they’re about to take. There’s no chance of you seeing them right now because they’re on their way back to South Africa in the morning, so you can’t physically see them, but you can get on the phone with them.”

Now I faced the challenge of talking on the phone with some guys I’d never met. I wasn’t sure whether they knew me or not, so I had no cachet to play. Why would some alternative rock band out of South Africa know me? I was going to take a shot in the dark. I conferenced up with the guys and told them how great I thought they were and how great I thought their song was. I promised them that I would get their song to number one alternative. I told them they would be the first alternative rock success at our label. We started talking about music and I asked them some questions and discovered they were actually jazz musicians and very familiar with jazz fusion, which I grew up loving, so we shared our enthusiasm for Jaco Pastorius, the Mahavishnu Orchestra with John McLaughlin, Bitches Brew, all that. Instantly we found common ground and ended up having the greatest phone conversation in the world and the guys agreed, without them meeting me or me meeting them, based on the song I heard and my response, to sign with Epic Records.

At the Nickelodeon Kids Choice Awards with Meghan Trainor (Christopher Pol/KCA2015/Getty Images)

We put the record out not more than a week later. Boom. It goes on the radio. This was an alternative rock record, but everybody in the company had their radio on, because KROQ was going to premiere the song. Everybody in the company was excited—the hip-hop department, the pop department, the alternative rock department, every department—and everybody had their radios tuned to KROQ. When “Come With Me Now” came on the air, the entire office exploded. The company started to rejoice. You could feel the energy in the halls. It felt like Epic Records had been reborn.

At Grammy week 2014, the guys came to my hotel room to meet me. I’d finally seen them perform the night before, opening for an act called Imagine Dragons at the Wiltern Theater. I loved them and was so happy we’d signed them. We had a great meeting, sitting in my hotel room, talking about music, listening to songs, looking at videos of their live shows. After they left, their A&R man, Paul Pontius, who I had only recently brought on board the company, stayed behind. He had been with me for many years before at Island Def Jam and was responsible for signing bands like Incubus and Hoobastank. “I got something I want to play you,” he said.

He sent me an MP3. I opened it on my laptop and out came this charming voice: “Because you know I’m all about that bass, that bass . . . no treble.”

I was like, holy shit, play it again. This is a smash. “Paul, who is this?” I asked.

“I don’t know,” he said. “It’s a songwriter out of Nashville and this producer, Kevin Kadish, sent it to me. They’re looking to shop the song for an artist. I just wanted you to hear it.”

“Okay, who’s that singing?” I said.

“That’s the girl that wrote it. That’s Meghan Trainor.”

Meghan Trainor was a nineteen-year-old girl who grew up in Nantucket, but had been living and working as a songwriter for a number of years in Nashville. I couldn’t stop playing it. I knew this was a fucking home run. I couldn’t believe my ears. “Paul, I need to meet this girl,” I said, “so make arrangements to bring her into the office while I’m here in LA. I’ve just got to meet her and she’s got to sing for me.”

“She’s not so much a performer,” he said. “She’s a songwriter.”

Paul went about making arrangements for me to meet her and I kept playing everyone the song, “All About That Bass.” I was hooked on the song, the thing was so catchy and carried this powerful message of empowerment for the plus-size gals. I knew she had something special.

A few days went by, and, meanwhile, I agreed to audition a beautiful female vocalist from Madagascar. She was a gorgeous, young biracial woman with curly hair, skin that glowed. She played piano and sang, then sang along to her demo tapes. Part of me, the old LA, thought this might work, but I was still on the fence. I told her manager that I thought I would like to sign her, but would she bring her back the next day for a second audition. She said they couldn’t come back during the day, but they would return the following night for another audition.

The next day Meghan Trainor showed up at the Epic Records offices in Los Angeles. As usual, I gathered the girls, a couple of the A&R people, put everybody into an office, and Paul brought in Meghan. “How y’all doing?” she said.

She held a ukulele in her hand and exuded warmth and character. The moment she walked into the room, I started smiling. I couldn’t stop smiling and I wondered why. I loved this girl. She talked a little, made everybody laugh, and then started strumming her ukulele and singing “All About That Bass.” I looked around the room and everybody was smiling. The girl from Madagascar disappeared from my thoughts.

Meghan was nothing like any of the artists that I’d ever signed before. She didn’t have Rihanna’s looks. She wasn’t a crooner like Whitney Houston, Toni Braxton, or Mariah Carey. She was something different. And whatever it was, I couldn’t stop smiling. She did two songs and I asked her to step out of the room. She went down the hall to wait in a little room and I asked the people in the room what they thought. Everybody in the room said they loved her, unanimously. Paul went down the hall and told her she had landed a record deal.

When Meghan and her producer came to meet at my office after the deal was done, they told me that now that I loved the song so much, they wanted to keep it and not give it to another artist. I didn’t have to convince Meghan to become a performer, because the truth is, behind every great songwriter there’s an aspiring performer. Because when they’re born, they’re all the same. They’re people who love music and they’re people who have the gift. Maybe somewhere later in life they come to the conclusion that perhaps they shouldn’t be performers, but they’re all performers at first. She wasn’t even twenty years old. She was ready. “All right, baby,” she said. “Let’s go, boo.”

She talks like that. Speaking with Meghan is like eating comfort food. There is something so soulful about her, like there is an old black woman in there somewhere. When she calls you “baby,” it makes you feel good. Meghan didn’t have any doubts; she rose to the occasion immediately.

I was feeling good. I had signed the Kongos and A Great Big World and now I had Meghan Trainor and “All About That Bass.”

Meghan and Paul told me they wanted to make a couple of changes to the song, give it another mix. “I will hear of no such thing,” I said. “You’re not making any changes. By the way, you can’t even mix this. We’re going to put this out just like it is. I don’t want you to breathe on it. Don’t touch a thing. This record is perfection. This record is flawless.”

“But we didn’t mix it yet.”

“I don’t want to hear it. We’re mixing nothing.”

And we put the record out exactly as it was. The demo that Paul played me in my hotel room after the meeting with the Kongos is the very record that knocked Taylor Swift off the top of the charts and became a global smash that sold more than seven million copies. I had my first Epic Records number one. But the statistic that truly blew my mind was when “All About That Bass” became the longest-running number one in the label’s history, eclipsing a record set by “Billie Jean” by Michael Jackson.

At last, everything was happening at the same time and the company started to hit a stride, and in many genres: the alternative field with the Kongos, the pop charts with A Great Big World, a brilliant execution of Michael Jackson’s Xscape album, and, if that wasn’t enough, we signed a kid out of Brooklyn named Bobby Shmurda and his song “Hot Nigga” became the hip-hop phenomenon of the year.

But it wasn’t just that the hits had started coming, it was something bigger than that. As things at Epic took off, I began drawing together the different corners of my career, creating hits but also connecting my past to my present in new and unexpected ways. Such was the case when I signed the rapper Future.

Future was one of the first acts I signed when I got to Epic, but more than just a talent, he’s also steeped in my history. A cousin of Rico Wade of Organized Noize, Future was part of the next generation to emerge from the Dungeon Family in Atlanta. With this background, I knew he would be a different breed of rapper, and I couldn’t have been more right. He sings in a rap style or raps in a singing style—it’s magnetic, hooking you in a totally unique way. After a series of successful mixtapes, he finally released his debut album, Pluto, in April 2012, which included the big hits “Tony Montana,” featuring Drake, and “Magic,” with rapper T.I. He rolled out hit after hit. The true revelation, though, came with his third album, DS2, which exploded to the top of the charts when it was released in July 2015. That launch was a smash, but two months later, he was back with a joint mixtape with Drake, What a Time to Be Alive, that proved just how insatiable his drive is.

Future’s talents also lie beyond his own music. He is equally capable of writing and producing hits with other artists, such as Rihanna and Ciara, and that has quickly cemented him as one of the most important artists on the label. Future is turning out to be the crown jewel of Epic, but to me, my bond with his music extends far beyond these last three years, all the way back to Atlanta.

I had a similar run-in with my past when I signed Travis Scott. T.I., another alumnus of LaFace University, brought him to Epic. Travis is a visionary rock star cut from the Kanye West cloth: graphic designer, director, songwriter, producer, and one the most electrifying performers I have ever worked with. One of the things I saw in him soon after he signed was the sweep and depth of his talent. His creative energy is a force of nature, and even before he’d put out a thing, it was clear he was destined for greatness. We had him on the label for three years before we released his first studio album, Rodeo, in September 2015, but once he was out there, the word of mouth started to take hold pretty rapidly, as his hit single “Antedote” landed him a slot on his first arena tour, with the Weekend. The album made number one on the rap and hip-hop charts, but we had to settle for number two on the pop charts. Like Future he is able to make records for himself as effortlessly as he does for many other artists, including Jay Z, Kanye, and Rihanna, whose single “Bitch Better Have My Money” he co-wrote and produced.

Both Future and Travis are prolific young musicians who constitute the future of Epic Records, but my satisfaction in their success runs deeper than just record sales. Each of them in their own way speaks to my past and where I’d come from. I’d started my time at Epic by chasing the sugar-coated pop that was so unnatural to me, but as I rediscovered my ear for talent, it opened up new possibilities from the entire breadth of my career, reminding me of how I’d gotten to where I am. I was drawing on my history in order to discover new voices and make an impact. With Kenny’s words still echoing in my head, I knew that my instincts and my taste—and above all my drive to make good music—were at the root of this resurgence. I’d brought the music back into my living room and it sounded better than I ever could have imagined.

So my little label was starting to kick in and attract an even higher caliber of both creative and executive talent. Suddenly Epic Records was the place to be.

The real success of a label is measured by its ability to attract talent, and we started to attract real competitive talent. When I first took office at Epic, the label was on the brink of closing the doors and turning out the lights, and we successfully brought it back.

We accomplished this turnaround in difficult times, when the record industry was still adjusting to the realities of selling fewer records, struggling to find its way. This is a much more challenging proposition than when Kenny and I were the songwriters or working with all the different producers. We did this with no help, no mergers, no acquisitions, no big superstars handed to us, no nothing. But I’m like James Brown. I don’t want anybody to give me anything. Open up the door, I’ll get it myself.

Still together after all these years

Today I am trying to dig the roots even deeper into the earth, into the soul. I am surrounding myself with friends and family who represent my musical legacy. When you come to my home, you should feel me, the history of me, who I have been and who I am always going to be. I brought back Mariah Carey and Jennifer Lopez, who both have history not only with me, but with Epic Records as well. I signed Outkast again and brought Puffy and Bad Boy Entertainment to Epic. We are aggressively seeking and finding new talent—that is the lifeblood of the industry and my specialty—but I want to mix and merge that with my life and my work. These artists are more than mere metaphors; they are the giants who helped make me who I am.

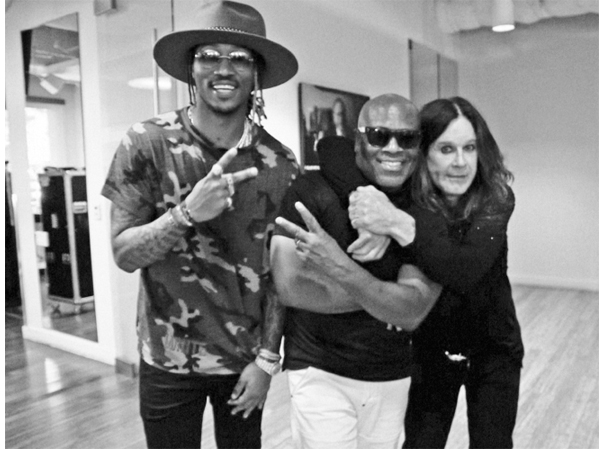

Standing between a legend, Ozzy Osbourne, and a “Future” legend (Anthony Saleh)

That way I will have a much greater chance to see into the future and to attract the future talent, and that was exactly what happened. At the 2015 Grammy Awards, I was back in the audience with acts in the running. Meghan Trainor was nominated for Song of the Year and Record of the Year, the two big ones, and A Great Big World was nominated for Best Group or Duo in Pop. Meghan didn’t win, but damned if A Great Big World didn’t walk away with the trophy, just as I had predicted, the first new generation on Epic to win a Grammy. All that made me happy, and made me feel that we’d gotten our company on track. What we will become is yet to be seen, but from where we have come, it’s clear that we’ve improved. We’re no longer a work in progress. We have progressed.