3

THE REAL DEELE

When I came on the scene, Cincinnati had been turning out funk for years. Of course, James Brown had begun it by recording for King Records in Cincinnati and making the city one of the secret hot spots of funk in the country. But over the years, what he’d started had just kept going.

In 1970, Bootsy Collins was a nineteen-year-old bass player working around town in a band called the Pacemakers when James Brown fired his entire band over a pay dispute and hired the Pacemakers on the spot as his new backup group. A year later, Bootsy returned to Cincinnati to begin his solo career when he decided to join Funkadelic instead. Similarly, Roger Troutman and his brothers used to gig around Cincinnati before changing their band’s name to Zapp and being discovered in 1979 by George Clinton of Parliament-Funkadelic.

After everything fell apart with Essence, I was determined to take charge of my musical destiny, and with Cincinnati’s funk history, the first step was getting back there, which took a couple of months. There was never any official discussion about Essence breaking up—everybody simply went their own way. The other guys left for Cincinnati immediately, and Kayo and I stayed in Indianapolis. We lived in our girlfriends’ houses. Candy hid me in her parents’ basement, and we would have to wait for her mother to come home and give her a couple of dollars to go buy some eggs for dinner.

I was in Indianapolis for a couple of months, sleeping here, sleeping there. I stayed on the living room sofa of Candy’s friend Brenda. All the time, I was writing songs. I’d actually started writing when I was about twenty-one years old, late, but I’d never shared my songs with the band, because I was too shy. Now that the band was done, I just wrote on my own. I didn’t have my instruments, but I wrote on a pad and hummed the tunes to myself. Brenda had a copy of the new Diana Ross record, “I’m Coming Out,” and I listened to that record over and over. That record made me realize that music was changing. We were coming out of the disco era. I could hear it. That was disco music, but disco music with a rock flair. “I’m Coming Out” came from someone I think is one of the most talented writer-producers in the world, Nile Rodgers. I slept on Brenda’s couch and listened to “I’m Coming Out” for days until Candy told me I had to leave. It was all coming to an end. It was time to go home.

I bought a round-trip Greyhound bus ticket for fourteen dollars. I cashed in the second half of the ticket when I got to Cincinnati so that I could help buy food for my one-year-old son, Antonio. I was doing what little I could to help support him.

Once we were both back home, Kayo and I started meeting in his mother’s basement, where she let us set up our equipment. One day I sat at the little makeshift bar down there reading an Ebony magazine story about Lionel Richie and the Commodores, how a groupie went all over the country on their bus with him. Talk turned serious and I expressed my strong feeling to Kayo about our need for a handsome, charismatic lead vocalist.

“What about Darnell?” he asked.

I can’t say I knew Darnell Bristol that well in high school. We lived in the same Mount Auburn neighborhood. He used to walk past my house on his way home from school and would always wave. He was one of the Backstabbers in choir class and he could sing. He was tall, good-looking, and skinny, with good hair and light skin. I had always been impressed with him, but I also wondered if he could go the distance. Revisiting it that day with Kayo, though, I thought he might be exactly what we needed, the perfect balance of talent and appeal. Kayo called him.

They talked on the phone and Kayo hung up. “Darnell is interested,” he said. “He’s going to come over.”

“When’s he going to come?” I asked.

“He’s going to come out today,” said Kayo.

While we hung around and waited, I worked on a song. Darnell walked in. I hadn’t seen him since high school. He was the young adult Darnell, not the kid I knew in school, and he looked amazing. And so cool. He had on jeans and boots, and a Members Only jacket, which was hot at the time. He had the Jheri curl, long, shiny ringlets of hair, and he had a striking resemblance to Prince. He hadn’t been playing music professionally—he was working at a car wash with his father—but he had been singing as a hobby and keeping up with all the latest. In fact, he seemed a lot hipper than we were, more in touch with what was happening, his finger more on the pulse.

While we had been waiting on him, I had finished a song that Kayo and I had been writing about President Reagan called “Mr. Clever” (those two would call me Mr. Clever after that for a while). After we talked for some time with Darnell, I pulled out my lyric pad and asked him if he would try the song. He sang the hell out of it.

With Kayo and Darnell in the fold, along with Larry and Tuck from Essence, we added a saxophone player and put together a new edition of Essence. We rehearsed in the basement of Darnell’s mother’s house for a gig we booked in Louisville, Kentucky. At the gig, some of the guys never showed for sound check. The show was a disaster. I knew this group of guys wouldn’t last. It meant so much to me and so little to them. I didn’t even bother to say anything. I simply told Darnell—whom we had taken to calling Dee—and Kayo, “Fuck these guys. Come with me.”

A couple of days later, when we were back in Cincinnati, Kayo and Dee came to my mother’s house, where I was living. She had moved from Madisonville back into the inner city. She had bought herself a little two-bedroom house in Mount Auburn, small but perfect for her and my little brother. Understandably, she was not happy about me coming back at age twenty-four. I didn’t have a dime and had no real plans. I must have seemed like the biggest failure in the world.

One day, when she was at work, Kayo, Dee, and I held a conversation about our future. We talked about how we wanted to put together a serious band, a commercial enterprise with genuine appeal, a group that could land a record deal. That’s when Dee named the band. “Let’s call the band the Deele,” he said.

The Deele would be where I learned everything I needed to know about the music business. This was where I came to understand songwriting, record production, the importance of image, how record companies worked, and what managers did. The Deele was my college education.

Right from the start, I knew our band needed a strong concept behind it. Dee was a huge Prince fan and wanted our band to be similar to the bands that were breaking out of Minneapolis. Prince and his crowd—the Time, Vanity 6, André Cymone, Jesse Johnson, producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis—they had the funk, but they went punk with it and mixed their funk with new wave and rock. It was a new breed. They were leaders, setting the styles and rewriting the rules. They were cultural. We looked at all the fanzines and studied their style. We analyzed the way Prince wrote songs. We checked out the way the Time sported that street-smart sarcasm.

Dee suggested we call Carlos Green, another guy we knew from Mr. Brown’s class in high school. “That crackpot?” I said. “Can he sing?”

I had known him as Carl Green when we were in junior high school. I went to school with his sisters. We used to play football together. He was a funny guy, always cracking up everybody, but I didn’t take him seriously and had no idea if he was talented. But when he showed up at my mother’s house, he had the same energy as Darnell. He was tall, slender, good-looking, had the right hair, the right attitude, and was a Prince fan. It was all there.

We brought back guitar player Steve Tucker—Tuck from Essence—and rehearsed for a few weeks, working up a bunch of songs we had written. Even though I’d been writing for a few years, I was still nervous about my work. The other guys could really write, so I was always a little embarrassed to let them hear what I was doing. I probably wrote fifty songs that nobody heard.

Each one of us took turns letting the band practice at his mother’s home. We went house-to-house after each new mother got tired of hearing the racket. Everything changed. We went from being this drab funk-jazz band to being a kind of Prince knockoff band. We started dressing the part. We played our own original songs. Our only covers were Prince.

I called the owner of the Zodiac in Indianapolis, where Essence used to play for never more than a few people. I told him I had a great new band and I needed a week’s work. “All right,” he said. “Bring them down. I will give you one week. I’m telling you right now that if this isn’t any good, don’t ever call me again. I’m telling you that because I put up with your shit for so long and if this isn’t it, that’s it.”

He gave us a date and we went back to Indianapolis. The first night the Deele played in the Zodiac Lounge, it was about half full. Second night, three-quarters. Third night, the club was packed. Fourth night, the club was filled, with people standing outside. By week two, we were a sensation. We cut back from four shows a night to three and raised our price with no complaints from the club owner. Indianapolis was different this time. Crowds came to see us. The club owner was nicer. The girls were prettier.

The Zodiac was the center of our life. Josie fed us burgers from the kitchen. The Thirtieth Street Big League, the local street enforcers who also frequented the club, were our friends. George, the big gangster who worked the door, would always let us in free. If the owner was at the door, he made us pay. We took a week off while the club featured a third-generation version of the Ohio Players, one that included the original sax player, Satch, but not the star guitarist Sugarfoot. George slipped us in to catch the act and we couldn’t keep our eyes off the Sugarfoot replacement on guitar.

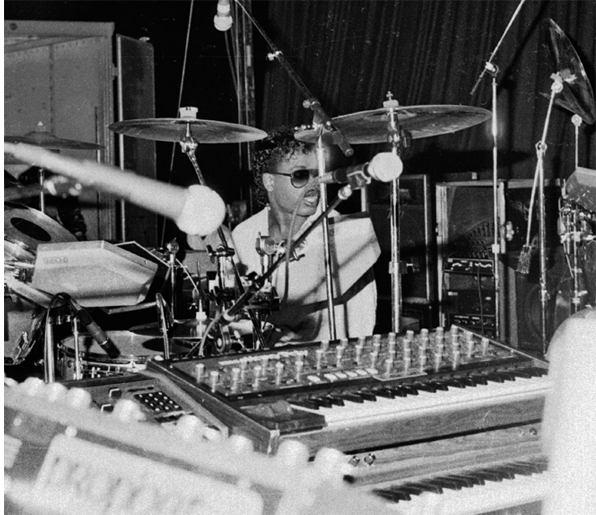

For people who only need a beat (Courtesy of Michael Mitchell/Perspective Image)

He was tall and handsome, had the hair, played wild and crazy, and was all Princed out. We instantly knew he could be our Keith Richards to Dee’s Mick Jagger. We introduced ourselves to him. His name was Stanley Burke, but everybody called him Stick. We talked with him a little bit, and, because he was clearly a better fit, we asked him if he was interested in taking Tuck’s place in our band. He finished the week at the club and never went back to the Ohio Players. We took him over to Kayo’s girlfriend’s house, where we were all living by then, and he joined the band.

We quit the club and concentrated on songwriting. We bought a four-track tape recorder with our earnings. A friend let us set up our gear in his basement, and I stayed down there for hours, learning how to work it. Stick knew how to record on the four-track. After playing for the past four or five years in a Top Forty band, I knew nothing about recording, but we started turning out demos when we weren’t playing at the club. I started to become a master of drum machines and to figure out recording. Stick sent some of our demos to a friend of his, a postal worker in Cincinnati who had a few dollars, and he agreed to pay for some studio time.

We went back to Cincinnati and into the studio to begin working on recordings, but we needed a keyboard player. We were like a rock band—two guitars, bass, and drums—and that didn’t work. At the Zodiac, we’d hired a sideman called Hollywood to play keyboard. Back in Cincinnati, we brought in another friend, Bo Watson, the whiz keyboard man with Midnight Star. He played on our track “Turn It Out” and liked what we were doing so much, he told Midnight Star’s manager, Pablo Davis, who came to the studio to listen with Reggie Calloway, the leader and producer of Midnight Star. They loved the music and told us they wanted to sign our band to their MidStar Productions. Reggie told us if we were signed to a major label, he would produce our album.

The next day, I went back to the studio to watch Midnight Star record, and that’s when I connected with Kenny Edmonds, who would eventually become my songwriting partner and a performer in his own right known as Babyface.

Prior to seeing him in the studio that day, I’d known Kenny a bit, and we’d circled each other a couple of times. When I was in Indianapolis, his band Manchild had a record deal out of Chicago and a regional hit, “Especially for You.” I went to see the band with my friend Toby, who pointed out the dark-skinned, left-handed guitarist at the side of the stage. “The little black motherfucker on guitar is great,” Toby said.

I used to spend time befriending Manchild’s manager, Sid Johnson, and he would play me these incredible demos Kenny made. Sid always told me he was going to introduce me to Kenny, but he never did. When Kenny came to see the Deele at the Zodiac, I recognized him. He was a member of a much more successful band, so seeing him there in the front of the club was a big deal to me. I went up and introduced myself after the set, but we didn’t exchange more than a few words. I didn’t think he liked me.

The next run-in I had with Kenny had come when I was back in Cincinnati and I’d received a call at my mother’s house from Hollywood, our keyboard sideman at the time. He was sitting in a Flint, Michigan, hotel room with Kenny. I played them our demo of “Turn It Out” over the phone. At the time, they were working in a Top Forty band called the Crowd Pleaser full of middle-aged musicians who still thought they had a chance of making it even though they were working at clubs in out-of-it Upper Michigan. The Deele had all gone “breed”—the term we used for the new style out of Minneapolis, an androgynous look that had the men in the Deele wearing makeup and leggings. Next to us, Kenny looked like a square.

Hollywood said Kenny wanted to talk about joining the Deele. “Kenny’s really talented, but he’s not breed,” I told Hollywood. That was the last time I had crossed paths with Kenny.

I walked into the studio in Cincinnati that day just as Midnight Star was beginning to cut a demo for a song called “Slow Jam.” The studio was dark and the singer was barely visible from under the shadows of the vocal booth. I couldn’t make out who it was, but, man, could that cat sing. When he finished the take and walked out of the booth, I recognized him.

It was Kenny, but now he was full breed. He had the London Fog overcoat. His hair had grown out more beautifully than mine. He looked like us.

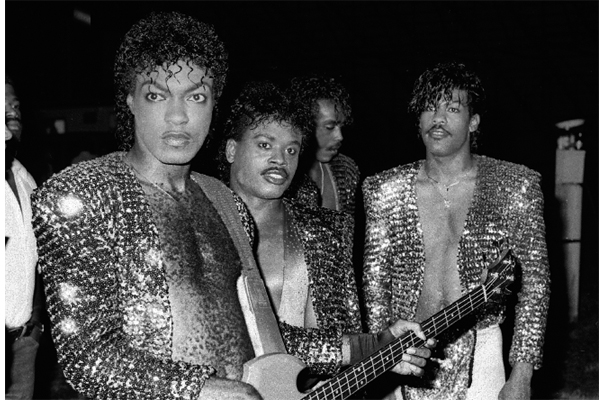

The Deele—full-on ’80s androgeny! (Courtesy of Michael Mitchell/Perspective Image)

“That was amazing,” I told him. He remembered me and told me how much he dug the track I’d played him and Hollywood over the phone. This time, we hit it off immediately.

Kenny was twenty-four years old—three years younger than me. He went to North Central High School in Indianapolis and came from a family of brothers. His mother, Barbara, supervised a pharmaceutical factory, and Kenny had been committed to a career in music since he was in the eighth grade and his father died from lung cancer. Kenny was also signed to MidStar Productions, and they were developing him as both a songwriter and as a potential future solo artist. All of us spent the next several weeks writing songs with the guys in MidStar, including Kenny, who was great with the Teac four-track recorder and produced our demos. He was also one of the best songwriters and guitarists in our crew. Kenny had learned how to overdub background vocals by himself. He made the demos sound like records.

Kenny and I struck up a friendship. We had chemistry. We liked talking to each other, liked being around each other. In this free-flowing writing environment, Kenny was clearly far advanced as a songwriter. Kenny was different, though—he was special—that much was obvious to me. He was so talented, so superior to the rest of us, that I was secretly shocked he liked our stuff as much as he did and that he wanted to work with us. He watched me at one writing session and told me he liked what I was doing and that we should write together. It was his suggestion, and I was somewhat surprised. I knew I wasn’t on his level as a songwriter, but I was eager to work with him and figured I could learn a lot writing with Kenny.

The session began with him playing me his songs. His demos sounded fantastic; they sounded like masters to me. Only later did Reggie Calloway explain to me there wasn’t enough dynamic range on the demos to match the other masters. But even his simplest demos were brilliantly produced. He had been writing for a long time and had stockpiled a lot of material, so at first he was playing me things he had already finished. Eventually, when he would play me something that wasn’t finished, I might offer a suggestion. I might say something like “I love this track, but right at that bar it should have gone to a bridge.” Kenny began to take my ideas and embellish them. Our writing together started as me listening to his music and finding the hole that needed to be filled. He began playing me everything he was working on. It was the beginning of our parallel journey.

We had lived in the same town for five years, worked the same clubs, knew some of the same people, but it wasn’t until we came together that we hit the fast lane and things began to click. Our first big break came when we both signed deals with MidStar Productions.

Although I didn’t notice it at the time, this might have created some tension with the other guys in the band, because after all the years I’d spent with Kayo, Dee, and Carlos, suddenly I was giving Kenny my undivided attention. We were eating meals together, playing Pac-Man.

Kenny stayed in Cincinnati, working on our demos. He went back to Michigan and then came back down and spent a month polishing our demos and writing songs. We wrote “Baby I’m Crazy about You.”

Our living conditions had come a long way from the apartment on Thirty-Eighth Street in Indianapolis. The management company rented us a three-bedroom house, and we set up a demo studio in the basement. It hummed like a factory. Songs were being written at any time of the day by someone. We recorded around the clock. When we weren’t working at the house, we were over with the Midnight Star guys writing with them. They had the rehearsal room, which was like a studio, and everybody’s bedroom had a keyboard, a drum machine, and a tape recorder. We lived in this culture of writing songs. Once during a party at the house, I snuck off to work on a song. I even sang the demo while the party was going on. I fell asleep, but when I woke up, the guys were standing around my room listening to my voice on the tape. I was startled to have them hear my non-singing. We had food, a van, and a little pocket money, and we were surrounded by a newfound bunch of really talented, like-minded people.

We were teaching ourselves songwriting—it was like record camp. Encouraging and inspiring—and sometimes competing with—one another made us an intensive study group in the fundamentals of the craft. As I worked with the other guys, I could feel my confidence grow and discover more that I had to contribute.

We got the demos done and Kenny went back to Michigan. He was aiming for a solo deal, and his involvement in the Deele was up in the air. He would work with us on music, but when we held band meetings, he would have to leave the room. There had been some discussion as to whether he should pose with the other guys for the band photo to go with the demo, but, in the end, he posed separately and we were photographed without him.

When Midnight Star completed production of their new album No Parking on the Dance Floor, their manager, Pablo Davis, and bandleader, Reggie Calloway, went to Los Angeles to turn in the album to Solar Records. While there, they planned to shop our six-song demo for a major deal. Within days, Pablo called and said he had two record labels interested—Quincy Jones’s label, Qwest Records, and Solar Records, run by Dick Griffey. As much as I respected Quincy Jones, Solar felt like home, not only because of Midnight Star being on the label. My high school music teacher Mr. Brown’s group, the Mystics, had moved to Los Angeles, changed their name, and signed with the label. As Shalamar, the group had gone on to become one of Solar’s big acts, although, sadly, Mr. Brown developed the deadly disease lupus, and he never recorded with the group.

Solar Records had been in my sights for a long time. Years earlier, I had sent a demo to Solar and had gotten a rejection letter that I kept as some kind of badge of honor. Even though they turned me down, the fact that I got the letter made me feel like I was in the game in some strange way. Solar was the place.

The first person I called was my mother. I was never a mama’s boy, but it was all about her for me. It mattered to me that she knew I was making it. The second call was Kenny. I reached Kenny on the phone in Midland, Michigan, where he was playing with the old guys, and told him the band had landed a record deal. “We want you in the group,” I said.

It hadn’t been easy. I had to cut a deal with the other members. Kenny asked what he would do and I had to tell him that the offer came with one stipulation—he couldn’t sing any lead vocals. He could play keyboards and help out with backgrounds, but no lead vocals. The matter had been much discussed while Kenny was away in Michigan. Dee and Stick, as singers, were protecting their turf. Carlos, who never saw himself so much as a lead singer, didn’t care, and Kayo had been a hundred percent with me about bringing Kenny on board from the start. Once it was agreed that Kenny wouldn’t sing, everybody was for it.

As I explained this caveat to Kenny, I reminded him that he would be making his own solo album someday and he didn’t need to sing in this band. Kenny had put plenty of work into the tapes that had gotten us the deal, and he was as proud of the music as we were. He had never been the lead singer in any of the groups he belonged to and was happy to play guitar and keyboards, doing background parts. He was glad to know he would be part of the adventure and we wouldn’t be leaving him behind. He was never a guy to get too excited.

“I’ll be there Sunday,” he said.

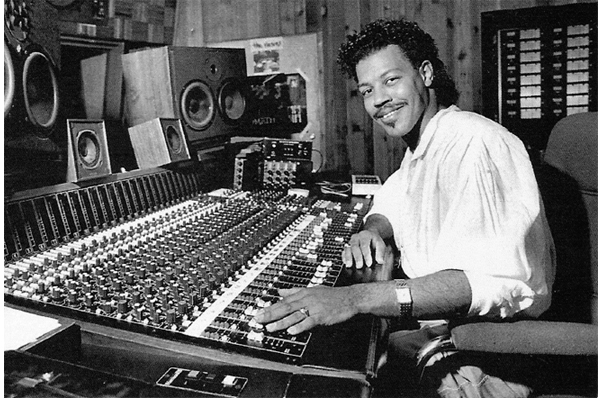

Super producer Reggie Calloway in his office at the board (www.cincinnativiews.net;)

When Kenny arrived in Cincinnati, we immediately started production of our first album. We had enough material for the entire album, but we all continued to write. Reggie Calloway took the helm as the song picker and producer. The first piece he picked to record was a song I wrote with Melvin Gentry of Midnight Star called “Body Talk.” I still wasn’t a great writer, but I did have some good instincts, and the guys always liked my taste and energy. Kenny thought more of my writing than anyone else did. I never did know what he heard in me, but strangely enough, I wrote the band’s first hit. It was just something I was humming when somebody else pointed out that it was a pretty good tune. I finished the song and brought it to the studio the next day.

When we made the demo, Dee didn’t like the song and refused to sing on it. So Carlos, in true Carlos fashion, stepped up and said he would sing it, even though, strictly speaking, he wasn’t the lead singer in the group. Funny how things work out.

When “Body Talk” came on the radio for the first time, I danced around like my crazy uncle Albert did when I was a child. It sounded so good—drums were sharp and tight, Kayo’s bass sounded wicked and funky. And, of course, that was Carlos’s voice coming out of the radio. The song started gaining traction when it was released in January 1984 and climbed all the way to number three on the R&B charts.

The phone rang in my apartment and I answered. A deep voice on the line spoke to me. “Antonio, Dick Griffey,” he said. “I wanted to call and offer my congratulations. You guys have a hit record.”

The Deele and friends—curls activated (Courtesy of Michael Mitchell/Perspective Image)

Chills went down my spine. I had never met or spoken to Dick Griffey before. I certainly knew who he was. Before he was the head of Solar Records, Griffey had been the talent coordinator for TV’s Soul Train, the popular show created by the impresario Don Cornelius. Griffey and Cornelius started Soul Train Records before Griffey split off to start his own label, Solar. He was kind of a junior Berry Gordy at the moment—Solar was like a little Motown, spitting out hip, cool hit records by Shalamar, the Whispers, Lakeside, Dynasty, Klymaxx, and our pals Midnight Star. No Parking on the Dance Floor, the Midnight Star album that Pablo and Reggie had delivered when shopping the Deele demo, went on to become the first long-playing record by a black act to sell more than two million copies, although the record was little recognized outside the black community. “Freak-A-Zoid” was a runaway smash single. The gold record award they gave me for my contributions to that album was the first plaque I received, and I immediately gave it to my mother.

In addition to his deep voice, Griffey spoke with authority—you could tell he was a serious guy. He asked a few questions about how the recording was going and said he looked forward to meeting me in person. As it turned out, I took my first airplane ride and went to Los Angeles to complete production on one unfinished track, to polish off the mix, and to master the album. It didn’t occur to me that I hadn’t been on an airplane until I actually got on one, and I guess I was a little green. Carlos tricked me into pulling down the oxygen mask before takeoff, which caused a minor scene with the stewardess. I met Dick Griffey at the Solar offices, where I also ran into Howard Hewitt, the lead vocalist of Shalamar, as he was leaving the building.

“Body Talk” opened doors for us, most notably an offer to be an opening act for Luther Vandross and DeBarge on a forty-city national tour. Outside of those first few weeks at the Zodiac, our band really hadn’t played live. We concentrated on songwriting and making demos. The opening dates were at Market Square Arena in Indianapolis. Back home. Only, the worst winter ever hit in 1984, and freak snowstorms caused the first shows to be canceled. When we did finally take the stage, nothing worked. Stick went crazy. Kenny couldn’t breathe. The whole thing flew by in a dizzying blur.

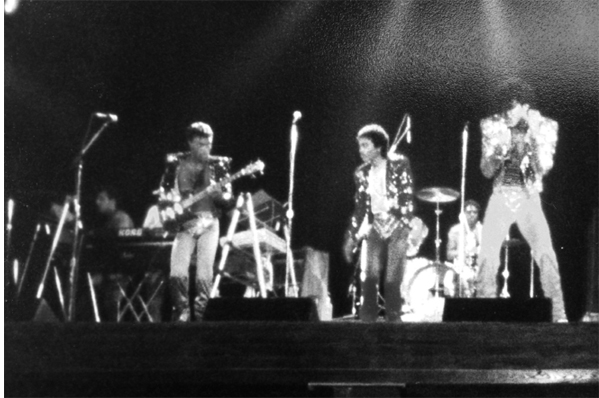

The Deele performing at Bogart’s in Cincinnati, Ohio, 1984 (Courtesy of Sheri Roberson Drye)

We had been working on our image. On the album cover, we were a bit more street, wearing tough-guy leather with an air of confidence and testosterone that rock bands always had. For the show, we wore these cheesy sequined jackets in bright colors that more closely resembled some pop act like the Sylvers or something. We also wore too much makeup. We had been aiming for the androgynous look that Prince and the Minneapolis crowd practiced so well, but Stick and Dee decided to take it a step further. Not only did they cake on the makeup, but they also smeared bright red lipstick on their lips.

After the terrible show, one of the producers took us aside and threatened to throw us off the tour. “I just got word from the boss that if you don’t take off the makeup and lipstick,” he said, “they won’t do one more date with you. We are not doing a Dynamic Superiors.” (The Dynamic Superiors were an openly gay band at the time.)

Kenny and I were the only ones who knew how bad it was, but we kept our disappointment from the other guys. We talked about it privately. Unfortunately, on that tour, we never got any better. We could play, but beyond “Body Talk” we didn’t know how to perform. We didn’t know how to win over an audience that wasn’t giving any love. You have to figure out how to get to them. We had no idea.

In particular, Stick didn’t know we were bad. He always played out of tune and all over the place, but with a confidence that worked. As we struggled, though, Stick developed more and more of an attitude. He was frantic and unpredictable onstage. In Little Rock, Arkansas, Stick decided to try another kind of makeup. He covered himself in whiteface. “You need to change that makeup,” I told him. “You can’t go on the stage with that makeup.”

He didn’t even listen. “Stick, you need to change that makeup,” I repeated.

“Fuck you, LA,” he said.

He did the show with the makeup. He wandered backstage after the show with a girl he picked up from the audience who must have been six months pregnant. He was drinking heavily and passed out on the long bus ride to Houston. We couldn’t wake him. He wasn’t breathing right. Something seemed a little crazy. He looked really sick. We took him to the hospital and they kept him overnight.

We did that night’s show without him and had our first good show. Other people on the tour noticed, too. We held a meeting in Stick’s room to check on his condition.

“We don’t know what is going on with you,” we told him. “You’ve been acting erratically and going off on people and what we think is that you need to take some time off. If you have some issues, we want you to go work them out and then come back.”

Stick felt bad. He knew he had fucked up. He mumbled something about how he was going to get better. He went around the room and gave everybody a hug, but when he came to me, he paused. “Fuck you,” he said. He never came back. You can’t say that to me.

Touring with Luther Vandross and DeBarge was a life-changing experience. We had graduated from the chitlin’ circuit and were now fully professional musicians. We were doing a nationwide tour with one of the greatest singers ever, and we were watching, learning, making friends, and joining this new fraternity of successful artists. We had our own team around us and were on the road. We had found our own style—it landed us a record contract, a smash hit single, and a national tour—but we had made the mistake of tampering with it, and, after a quick course correction, we got back on track. Once we established our groove onstage, we were rolling.

After the forty dates were over, we returned to Cincinnati. We went home to our apartments and relaxed. But when I asked our manager about how much money we had made after five months on the road, the news wasn’t good.

“You guys didn’t make any money,” he said. “You did it for exposure.”

We came back broke. It was heartbreaking and infuriating. I didn’t know what to tell the fellows. We were going to have to move back in with our families. We held a meeting and came to a decision. I would take over running the operation, and our manager, we fired his crazy ass. I knew nothing about managing, but I figured I couldn’t do any worse.

I called our booking agent, a young buck about my age, who told me he could find more work. “The roof’s still kind of hot,” he said.

We went back out on the road. I paid the expenses for the tour out of our money and I took the rest of it and brought it all back home. I rented three apartments on the edge of a golf course in suburban Cincinnati, country club living, and installed two band members in each apartment. I thought I had it made.

We went back to writing and making demos, starting work on our second album. When Midnight Star came back from touring for almost a year—and selling way more records than we did—Pablo told them they were broke, too. They sued him and, as a result, wanted nothing to do with us anymore. They had lost interest in us anyway. Reggie had a way of working in the studio that undermined our confidence. He told Kenny he couldn’t hold his notes long enough. He made record production seem like rocket science, saying things like, “You need to think it through,” and, “I don’t know. Maybe. It’s not an easy thing.”

We’d never been on our own in the studio and didn’t know what to do. We kept writing songs and sending demos to the label. I got a call from Dick Griffey asking when production was going to start. I told him we were having difficulty with our producers. He told me he would work to resolve the issues and come to Cincinnati. The mountain was coming to Mohammed.

This would be the first time someone of Griffey’s status had ever visited our apartments. I was proud to show off the new digs, my palatial two-bedroom apartment, and equally nervous with anticipation. When he walked in, I offered him a beverage. He asked for a glass of white wine. I filled a glass with ice and poured the wine over. He shot me a condescending look and I knew instantly what I’d done. Never serve wine with ice. I needed a few lessons in how to host millionaires.

We went upstairs to my room to listen to music, where I had my studio set up. My bedroom was a cocktail table, my studio equipment, and a sofa bed I rolled out to sleep in at night. Reggie came with him. We played a few songs without much fanfare until they heard “Stimulate.” I caught Griffey and Reggie giving each other the look—That one was pretty good.

Griffey leaned back in the chair. “Who produced the demos?” he asked.

“We did it ourselves,” I said.

“Well, you can produce your own next album,” he said.

That was the beginning of my musical production journey.