4

THE SOLAR SYSTEM

I was surprised to receive a phone call at my apartment from the Cincinnati funk legend Bootsy Collins after I got back from tour with the Deele in 1984.

“LA, it’s Bootsy, baby,” he said. “I heard you got that funk. Why don’t you hook me up with some?”

I ran upstairs to my makeshift studio in the bedroom and laid down a beat, threw on some keyboard, added bass. I pumped out a track for Bootsy—the first time I had written by myself since those days of writing in Indianapolis and listening to Diana Ross—and rushed a cassette over to the studio where he was. He took it home, wrote a song to it, and called me back.

“I think I got something,” Bootsy said. “Let’s set up a session and get this thing done.”

We went into QCA Studios in Cincinnati, where we had recorded the Deele’s album, to cut the track. I put down the drums first. Bootsy was playing his own bass part when Kenny walked into the studio, dropping by to check on me and see what was happening. Bootsy looked up from where he was sitting, his bass across his lap.

“Babyface!” he said without missing a beat.

Kenny didn’t laugh. In fact, he gave a slightly sour look, but it stuck with me. That weekend the Deele did a gig in Richmond, Virginia, and when it came time to do his part, where we would usually introduce him as “Kenny Edmonds” to polite applause, we announced “Babyface” and the place went nuts.

We’d shifted his identity. At the time, it seemed mildly inconsequential, but when it led to louder cheers, I realized we had done something significant. The name completes the package.

After the show, the girls all wanted to meet Babyface. With nothing more than a simple name change, he went from being mild-mannered Kenny Edmonds to being a star. I think it gave him more confidence in some crazy way. We had spent a lot of time trying to come up with a nickname for Kenny, but nothing had worked. All of us had nicknames—LA, Dee, Carlos, Kayo—and, after that one crazy moment that afternoon in the studio with Bootsy, now Kenny had one, too.

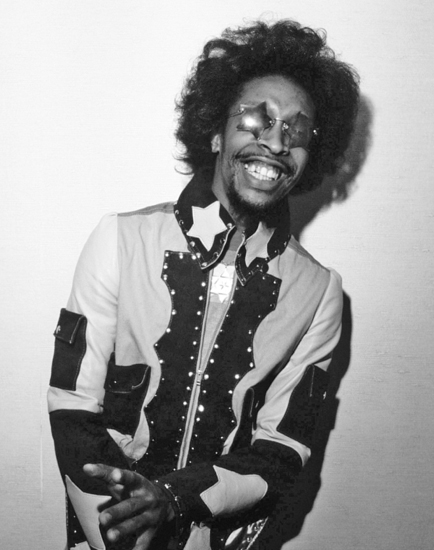

The legendary Bootsy Collins (Richard E. Aaron/Getty Images)

Babyface and I would unlock the mysteries of record production together. We were two young, hungry musicians eager to move forward, ready to expand our roles beyond that of being sidemen in a group, and we found in each other almost immediately a shared sense of purpose and an enthusiasm for learning.

I still worked with Kayo, but Kenny and I were becoming the team. We liked the same things, had the same work ethic. On the road, when the other guys would chase girls, Kenny and I would go back to the hotel room and write. I liked girls, but I liked music more. In Kenny, I found a kindred spirit.

Kenny liked to work during the daytime. I was more of a nighttime person, and I would often finish things at night that he’d started when the sun was still out. Kenny did tons of songs by himself, nothing to do with me, because he was a complete accomplished songwriter. He was a self-contained unit and could start and finish songs without any help. I, however, have always been a collaborator and didn’t often write songs from beginning to end by myself. Sometimes I might sketch out the skeleton of a song top to bottom, but for the most part I did embellishing and producing. Kenny was the poet, while I was more concerned with what a song would sound like.

In public, Kenny was quiet and shy, but privately he loved to debate. Kenny was patient. He always had time to sit down and talk about something. He was never too busy and there was nothing that wasn’t worth discussing. It was great for me to always have someone to talk with. And he had that golden voice.

And we would need it, because the Deele’s second album would be crucial to the band’s fate. The first album by the Deele sold a strong three hundred thousand copies, and “Body Talk” had been a big enough hit on R&B radio that the band’s next record would get a good shot. But we were a long way from made men.

The Deele went to a studio in Columbus, Ohio, to do the second album. I was nervous sitting behind the console as the producer for the first time. Dick Griffey passed me the baton, but there wasn’t any real reason behind that other than I had produced the demos and it was my band. He simply made me the producer. There was a skilled engineer next to me, but I didn’t have confidence. I never asked the guys—I simply took the job—and really didn’t know how they felt about it. As we went through the process and the songs turned out better and better, they grew more comfortable with the situation.

During the sessions, we got a message from Dick Griffey that he had heard the demo to a number Kenny had written called “Sweet November” and he wanted us to do the song. It wasn’t a song that either Dee or Carlos could sing, and when Dick heard the tapes from the sessions he called again, asking why he didn’t hear “Sweet November.” I told him we didn’t have anyone who could sing it, and he was confused.

“But isn’t that Kenny’s voice on the demo?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said, “but he isn’t the lead singer.”

Dick obviously didn’t have time for something that stupid. “This doesn’t make any sense,” he said. “You guys need to get this worked out.”

We held a meeting and Dee and Carlos refused to allow Kenny to sing. I called Dick Griffey and told him the band voted down the song.

“If you want to make a record for me,” he said, “it better have ‘Sweet November’ on it or there won’t be any record.”

I hung up the phone, secretly pleased that he had overruled my foolish band. I was getting closer to Kenny than those guys anyway.

We spent most of the day in the studio working on the song, trying to cut the track. For some reason, I decided to play live drums on the track. Oddly enough, I had not done that since Essence. All the Deele demos and records had been cut using drum machines. I owned every kind of drum machine and had become a master of programming drum sounds and adding live overdubs. I could make drum machines sound better than I could play. I made my beats sound any way I wanted. If I wanted a marching sound, I could create that. If I wanted an ensemble sound or the effect of a single percussionist, I knew how to use the machines in different configurations to create that.

But playing live drums on the “Sweet November” track that day, I couldn’t perform as a musician up to my standards as a producer. My ears had outgrown my ability. I kept speeding up, slowing down. Finally we gave up and I put the song together with drum machines.

I was sitting back in the control room, still shaking with frustration from recording the track when Kenny started to sing. It was like heaven opened up. We had been on tour with Luther Vandross and we had been watching the master of the soul ballad every night. We were inspired in the production of the song by Luther songs like “A House Is Not a Home,” but Kenny was magical. I snapped out of it as I listened in awe to Kenny, overdubbing his vocals and making the song into what I knew would be a hit record.

Once we broke the wall that Kenny could sing, the second album took on a completely different complexion. He sang another song he wrote, “You’re All I Ever Known,” and the most memorable numbers on that album happened to be his two songs.

Not even Kenny’s voice was enough to help the album, unfortunately. When we put out the single of “Material Thangz” in May 1985, it stiffed, so basically the album didn’t sell. The second album barely cracked a hundred thousand.

While we were in Columbus, we got a call from Dick Griffey, asking us to produce Carrie Lucas, a singer with a couple of dance club hits who also happened to be his wife. It was the dumbest song, a parody of “All This Love” by DeBarge. Kenny wrote it about Greg falling in love with Ginny, characters on the daytime TV soap opera All My Children, a favorite show of Kenny’s. We thought the song was a joke, but Dick Griffey heard it and thought it was a smash. We flew to Los Angeles through Chicago and did the session—the first time we were brought in to work with another artist. Now we were officially producers. Now we were Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis.

When we started the third Deele album in 1986, we were still living in Cincinnati. Dick Griffey asked me on the phone one day what I was still doing in Cincinnati. It was our hometown, I told him.

“You can make more money by accident in Los Angeles than you can on purpose in Cincinnati,” he said. “Why don’t you move to LA?”

Two days later, the game was on. I took my credit card—my first American Express card—bought airline tickets, and moved my band to Los Angeles. We also brought Daryl Simmons, who had been around so long we called him Silent Partner. Daryl and Kenny were childhood friends and had started out playing music together in Indianapolis. They’d both belonged to Manchild, before Kenny hooked up with the Deele. When the Deele started touring, Daryl came along to play keyboards and extra percussion. He soon worked his way into writing and playing on the records. By the third Deele album, he was indispensable.

We landed at a Holiday Inn in LA, where I seduced the desk clerk and she took care of everything until I went to the desk at one point and they took my credit card. By then we had picked up some scraggly manager named Dollar Bill Wallet from Cincinnati. He was always a hustler and, for a minute, we thought he was a pretty good manager. But he could never somehow manage to handle the $12,500 credit card bill. I needed my credit card back. He did nothing. We dumped him and called the record company to explain the situation.

The record company put us in an apartment complex called Highland Terraces on Highland Avenue off Hollywood Boulevard, dead center in Hollywood. We had been living in beautiful town houses in Cincinnati we rented for $500 a month. Now the entire band—except for Kenny, who was living with his wife, Denise, at a friend’s place—crammed into one three-bedroom apartment that cost $1,300 per month. But this was Hollywood. And when you’re in Hollywood, you’re in the game, the music industry, the film industry, the television industry, ground zero for the entire glamour profession. Every day I walked down Hollywood Boulevard from our apartment to the studio and drank it in. The rent seemed like a fortune, but I felt proud. I felt like I was living a pretty decent life. I didn’t have a car, but the studio and record company office was within walking distance. We set up our recording gear in the apartment and wrote every day.

We still didn’t have much money, and Dick Griffey offered me $5,000 to sign a contract as producer. He saw Kenny more as an important songwriter and encouraged him to develop a solo album. He put me to work producing other Solar acts like Dynasty and Shalamar. It was a kind of divide-and-conquer master plan, but Kenny and I saw too much strength in our collaboration to be pulled apart.

We were beginning to see ourselves as a team that was capable of finding songwriting work outside the Deele. The Whispers approached Kenny about recording some of his songs and having him produce the sessions, but he told them he wouldn’t do it without me. We wrote “Rock Steady,” copping the title from the brand of keyboard racks we had in our home studio, and never consulted with Griffey about the session. And we begin to rock/Steady rockin’ all night long . . . The Whispers acted as their own executive producers and cut their own deal with us.

When Dick heard “Rock Steady,” he knew what it was. We knew what it was the night we made the record. We knew that the record was superior to anything we’d ever recorded. We spent the night in the studio laying down the rhythm track, drums, bass, keyboards, and guitars, and then brought in the Whispers to sing background vocals. Right then, even before we cut the lead vocal, we knew we had a monster. I sat between those speakers and listened to the sound coming through and I really couldn’t believe what we’d done. We made songs daily, but this one was something different. It felt like God was in the room, and from then on, I’d seek out that feeling every time I was in the studio. Only during truly special sessions, though, would I find it. When it was released in June 1987, “Rock Steady” became our first Top Ten pop hit and was a number one R&B hit. It was the biggest hit of the group’s thirty-year career. To this day, you can’t go to a black wedding reception without hearing it.

I kept looking for a manager for the Deele because the band was an ongoing concern and my hands were full with writing songs and making demos. I ended up hiring a manager for the Deele named Don Taylor, a Jamaican guy who had handled Bob Marley. In fact, when assassins broke into his home to kill Marley, Taylor threw himself across Marley’s body and took five of the six bullets in his back. Marley escaped with a flesh wound to his arm. Taylor survived and moved to Los Angeles, where Dick Griffey introduced him to me. He signed both me and Kenny, but he was another tough guy. It didn’t last long.

He gave me grief over changing Kenny’s name to Babyface. When Taylor showed me the artwork for the album at his office, it said “Kenny (Babyface) Edmonds” on it.

“It’s supposed to say ‘Babyface,’” I said. “What are you doing?”

“That sounds kind of crazy,” he said. “We should make it Kenny ‘Babyface’ Edmonds.”

“Listen, motherfucker, I said it’s Babyface.”

I spoke plainly and loudly, in full shot of secretaries and other people working in the room. He stepped back and looked at me. I didn’t care. All I was thinking about was that I wanted his name changed to Babyface—I’m the art guy; you manage the business. He gave me a long, hard look and walked away, but he called me that night at home.

“I’m sending somebody over to get your little ass,” he said.

“You pay the rent, so you know where I live,” I said and hung up.

Nobody ever showed up. I sued him—because I was a crazy young man. That lawsuit tied things up for a while, until Dick Griffey stepped in, settled the beef, and made everything good.

Dick Griffey was a lot of things to me: a father figure, a tasteful gentleman, a charming ladies’ man, a tough guy you didn’t mess with, a passionate record executive, and a smart businessman. He used to share business strategy with me, explaining legalities, management tactics, and music publishing. He was Griffey U. I learned about artist imaging by watching him and observing the decisions he made. He was careful to sign only good-looking groups. He knew that while one band may play better than another, the one who could get on television had an advantage.

Early in my career, Griffey ingrained in me the ability to discern which artists could be telegenic and which would not. Of course, real music has nothing to do with what you look like, but there was a tendency to find someone who could play the part and come up with the fake music. As you raised the bar on beauty, you lowered it on music.

He could be funny, too. I remember complaining that five guys couldn’t live on the money he was paying us.

“Young man,” he said, “the record business doesn’t pay by the pound.”

It was through Dick that I came to be really comfortable in the studio, because he let Kenny and me use his Galaxy Studios downstairs from the record company office. That was where we got our advanced degree in how to make records. At Galaxy, we worked with a great engineer named John Gass, who taught me about the studio in a way that I hadn’t quite understood before. He showed me about expanding sounds, equalizing and mixing records, really understanding the dimensions of a mix: the highs, the lows, separation, panning—in other words, what gives a record punch and what makes it lush. Night and day, I attended these postgraduate seminars at that console in Dick Griffey’s studio next to John Gass.

Dick liked me. He laughed at me one time in his office when “Two Occasions” was on the charts. “You’re never satisfied,” he said. “Your record is number nine on the charts and what do you have to say about that?”

“It’s not number one,” I said.

Mr. Griffey was my teacher and my role model, my supporter and protector. I patterned myself after him. I studied him carefully and could imitate him flawlessly. I would call up the guys in the band and pretend I was him. “Dick Griffey here,” I boomed over the phone, and the guys would quake in their boots before I broke into laughter. “Hey, it’s me, LA.”

We were having fun and we were learning how to make records, but it all came at a cost. Solar Records was a limited universe. We had to work within a system with only a few acts. Griffey had me tied up with an exclusive contract as a producer, but not Kenny. Griffey saw Kenny as a songwriter and an artist (his first solo album that we did on Solar, Lovers, came out in October 1987). Our reputation was growing, but we couldn’t get anywhere with the other labels, who were all afraid of Griffey’s exclusive contract, whether Kenny was signed or not. Nobody would touch us. What’s more, Griffey never even paid me the $5,000 he promised me.

Griffey was a tough businessman. Kenny once asked him why we didn’t get money for our publishing up front like other writers did.

“You’re lucky because Berry Gordy took all of the publishing,” he said. “At least you get some of your publishing. All this shit isn’t free, Kenny.”

He was telling it how it was. I learned a lot from Dick Griffey, but it made me angry to be shut down by him. As I grew in the business and produced hit records, I started looking around.

About a year after I moved to Los Angeles, in 1988, I quit the label, and then worked hard to get Kenny released. Griffey wasn’t happy to see us leave and there were certain contractual entanglements that needed to be straightened out before we could. That took some time, but I was able to make it happen. It turned out to be the breaking point in my relationship with Dick Griffey, and while that disappointed me personally, I knew it was the right move for us professionally. It was what Babyface and I needed to take our success to the next level.

For the first time, we were on our own.