6

THE DIRTY SOUTH

The Deele might have been over, but as far and Kenny and I were concerned, we were just getting started.

In 1988, the industry had discovered us. Our records simply exploded that year. By the end of the year, we had two Top Ten hits with Karyn White and two Top Ten hits with Bobby Brown. Ultimately, we ended up with five Top Ten songs on Bobby Brown’s album Don’t Be Cruel, which hit number one on the album charts, sold more than twelve million copies, and was the best-selling album of 1989. We made number one on the R&B charts with a group called the Mac Band for MCA. We wrote and produced “The Lover in Me” for Sheena Easton, another Top Ten hit. We did “Dial My Heart” with the Boys on the Motown label and made the Top Twenty. We were cutting hits with another member of New Edition, Johnny Gill, and had more projects lined up than we could do. We were making culture.

After all that, we were officially the hot new songwriters on the scene. Pebbles and I moved out of the Highland Terrace into a little house in West Hollywood with three floors, a sauna, and an elevator. I bought all new furniture. I was beginning to feel like a citizen. I had a couple of cars now, and so did Pebbles. We were starting to live well. Her daughter Ashley spent a lot of time with us, and then Pebbles got pregnant with our first child.

We were hitting our stride, but then, in the first six months of 1989, three large earthquakes rocked Los Angeles. Neither Kenny nor I had ever been through anything like that, but Kenny in particular was really affected. He was frightened enough that he wanted to move. At the same time, Pebbles and I were having our own issues with LA, which had nothing to do with earthquakes. Suddenly, Los Angeles seemed like a small town and we felt hemmed in. Our success gave us the confidence to think about other possibilities—because of how we’d gotten into the business, we didn’t feel tied to any city. We started to talk about relocating, so that Kenny and I could begin our own label.

Kenny, Pebbles, and I brought a map into the studio and pinned it to the wall. Where would we go? How about Texas? Nice homes were affordable in Dallas and Houston, but it didn’t seem right for the music. We thought about the Bay Area, where Pebbles was from, but quickly rejected that idea too. Indianapolis, Kenny’s hometown? Scratch. Cincinnati? Scratch again. We talked about New York City, but hadn’t had much luck making records in that town. The only time we recorded there we made “Refuse to Be Loose” with the great Siedah Garrett, who’d written “Man in the Mirror” for Michael Jackson; it was the only record we made during that period that wasn’t a hit.

The three of us stood there looking at that map, and I do not remember which one of us said Atlanta, but after that, nothing was the same.

Atlanta was not on the pop music map. It was a large Southern city, but it didn’t feel like the old South. It was the birthplace of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., and the city where civil rights leaders Andrew Young and Maynard Jackson had been elected mayor. Atlanta had this robust history and an upwardly mobile black community. It felt like a city full of dreamers, a place where things could happen and a place that hadn’t been born yet musically.

It was a city that, in many ways, reflected what was going on with our music. Postdisco rhythm and blues in the MTV world had taken on a pop sheen, losing much of the raw, ghetto funkiness of the music I grew up playing. Like the black community itself, our music had taken on elegance, class, and dignity, without sacrificing any of the essential black ingredients—grit, sass, and soul. The more we thought about it, the better the idea of Atlanta sounded. We could own that town in a way we never could Hollywood. We would have first shot at all the talent and instantly be the biggest tree in the forest. It wasn’t some fully formed strategy. None of us were from Atlanta or had relatives there. None of us had even really spent any time in the town, but Atlanta it was.

For a while, Kenny and I had spoken about having our own record company. It seemed like the obvious next step. It would give us control over our creative decisions, instead of being at the mercy of A&R executives. We never really considered the business side of the equation, other than assuming we would make more money if we had our own label. We came up with the name LaFace while driving down Sunset Boulevard and talking about how all the hot new restaurants in town were “La” something—La Place, La Dome, La Anything. We made a contraction of our names into LaFace. Forming our own label seemed obvious to me, and Kenny went along.

In our years of working together, Kenny and I had learned everything about how to write, record, and produce catchy songs. Because of everything we’d been through together, we had a lot of confidence that we could translate those skills of making catchy records into discovering sticky talent for ourselves. Until now, we’d been following the lead of others, producing and writing what they asked us to; at LaFace we’d be following our own lead—we were about to get a crash course in the art of discovery, with ourselves as the teachers. I have no idea what made me think we could do it, but I didn’t have any doubts.

We had made a lot of our hits for MCA Records, so the next day I called the president of MCA, Irving Azoff. I told him I wanted to move to Atlanta and start the Motown of the South, LaFace Records. He loved the idea. I asked for $600,000. Not only did he say yes to the money, he also offered to book the travel, arrange the hotel rooms, and introduce us to Joel Katz, Atlanta’s international power broker. Two days later, the money was in our account.

I had never really been to Atlanta, other than passing through on tour. As I drove around the town with a real estate agent and saw the place, I started to grow fascinated. We could have some pretty decent lives here. We found this ritzy, gated subdivision in North Atlanta built around golf courses called Country Club of the South that felt right. Kenny found his house, and Pebbles and I got a place. Kayo came along, as did Kenny’s friend Daryl Simmons.

The stucco house that Pebbles and I bought was quite grand. The great room had twenty-foot ceilings, and a sweeping staircase led upstairs. The eight-thousand-square foot, five-bedroom house sprawled over a corner lot, occupying an acre and a half with beautifully landscaped gardens. We used a decorator from Atlanta and did the place in a combination of California shabby chic mixed with Southern charm. We finished out the terrace level with a movie theater, an exercise room, an extra bedroom, and a beauty salon that opened to the pool.

These were richly emotional days. Pebbles and I ran off to Las Vegas and got married. We were young and in love. She was pregnant with our son, Aaron. We brought her daughter Ashley with us to Atlanta, and Antonio Jr. came down from Cincinnati to live. I had always sent his mother money and did my best to stay in touch, but I had been largely an absentee father and I hoped to make up for that in some way. He started high school that fall in Atlanta. After all these years, I was finally in a position where I could buy some things. I was glad to buy my mother a house in Cincinnati, and she never had to work again. She and her sister Katrina were constant visitors at our new home in Atlanta.

Between Pebbles’s career and Babyface’s solo work, we were big-time for Atlanta. There was a splash in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. TV news covered us. When we moved, we rented one of those giant car carriers that auto dealers use to transport new cars and filled it up with our cars; Benzes, Range Rovers, Porsches. I remember that thing pulling up in the Country Club, a seriously uptight, exclusive little enclave. Back then, I didn’t give it a thought, but now I wonder, what the hell did the neighbors think?

My life had completely changed. I was running a record company and living in a mansion with my new family. I wasn’t rich—I went to Atlanta with $40,000 in the bank. We moved into this giant place that didn’t have curtains up yet. We felt like we were living in a fishbowl. That first night, Pebbles, Ashley, and I went out to dinner, and a terrible loneliness descended on us. We had moved to a city where we knew absolutely no one. What had we done to ourselves? And what were we going to do?

The first thing was to get the record company funded. Our intended deal at MCA fell through when Irving Azoff grew bored running a label and quit his job. Our industry godfather Clarence Avant, the same man who steered producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis to the top, took us to see Mo Ostin at Warner Brothers, Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss at A&M Records, and even arranged a meeting with David Geffen, who sent a car to the studio one Sunday afternoon to take us to his Malibu place for lunch.

I walked in and was greeted by a tall guy wearing an apron. “Hi, I’m David,” he said. I thought he was David Geffen. He pointed us to the deck and went back in the kitchen. When a short, casually dressed man came out and said hello, I looked puzzled and asked him who he was. “David Geffen, you schmuck,” he said.

Over lunch, Geffen was the charming host. He regaled us with tales of the record business and concluded by saying he wanted to make a deal with us.

A couple of days later, Clarence called to tell us David had changed his mind. “There’s one last meeting I want you to take,” he said. “I want you guys to meet Clive Davis.”

Clive Davis? I read his book when I was eighteen years old. He was the man behind Sly and the Family Stone, Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, Herbie Hancock’s Head Hunters, Chicago, and Blood, Sweat, and Tears. He had made Janis Joplin a star. I knew he was the guy.

We went to Clive’s Beverly Hills Hotel bungalow, where he had the air conditioner set to full chill. Everybody else had wined us and dined us, but we went to meet Clive around noon and he had a plate of cookies out. Where the fuck was lunch? We told him we were hungry and he ordered some sandwiches.

Clive was running Arista Records and had Whitney Houston and Kenny G, both at the height of their careers; otherwise, the label was not making an impact on youth culture. That didn’t matter to us—we loved him. He played us some records, we talked shop, held a nice, friendly meeting. Clarence called back and told us Clive wanted to make the deal. He would pay the million-dollar advance we wanted plus cover our overhead while we built a staff that the record company funded. I felt official for the first time.

Atlanta was not quite ready for us. There was no music business. There was no place you could rent a luxury car. Hell, there weren’t even rehearsal studios or equipment rentals.

We looked at every studio in town—and there weren’t many—and sort of settled on Cheshire Bridge Studios, where we’d cut Bobby Brown and Johnny Gill. The studio owner paid a visit to my home, where he let me know what a top dog he was while he flicked his god damn cigarette ashes on my Oriental rug. When Kenny suggested building a studio on my property, we got the builder together with a studio designer and made a two-bedroom guesthouse that was a replica of the main house with a studio, named LaCoco Studios, after our Lhasa Apso puppy, Coco. We were up and running in four months. The first thing we did was finish Pebbles’s next record, which had been going slowly because she was pregnant. Meanwhile, Kenny and I kept flying back and forth from Los Angeles, finishing his next Babyface album.

Once we had the studio built, the house turned magical. It became the castle of my kingdom, a busy hive of creative activities that went on day and night. My label was my life, and as it was a small, family-size company, we blended our social and professional lives seamlessly. I wanted to be around that kind of energy, right in the middle of it.

I made my home the center of everything. We kept a chef on duty around the clock in the main house. The terrace level was always humming with people watching movies, shooting pool, using the small demo studio, or hanging out in the beauty salon. It was our little recreation center, and we drew around us not only the artists and musicians, but the trainers, the hairstylists, all the kinds of creative people we needed. When the neighbors complained I was running a business in their residential community, I told the fellow they sent to interview me that I was a musician and I had a studio. My neighbor is an accountant—does he have a calculator? They left me alone after that. There were a lot of people coming to the studios, cars parked around and activity, but I never worked on weekends. I needed to make that commitment to my family and it was a strict rule.

After we’d set up shop, we quickly started checking out the local scene. Joyce Irby of Klymaxx, whom I knew from Solar Records and who had moved to Atlanta several years before, introduced me to Dallas Austin, a nineteen-year-old wonder boy I met at Cheshire Bridge. We instantly became good friends and started to spend a lot of time together in the studio. He already had a couple of hits, and when we opened LaCoco, Dallas came around a lot. He had a very different style from ours, hipper than we were. By this time, our sound had saturated radio, and I knew we had to broaden what we were doing. We’d had something like fifty songs on the radio; what we were doing was no longer new. Meeting Dallas was a breather, and it happened at the perfect time. With Dallas, we got another swing at the ball. I was already scouting for new sounds when we found Dallas. The first thing he did for me was a remix for a Pebbles song called “Backyard” featuring Salt-N-Pepa. When I heard what he did, I realized he was the hot young guy and I was now the older cat. I became the teacher who was really the student.

We were pulling together a clique, and Atlanta was getting to be our town. About the same time, Bobby Brown moved to town. He was officially Bobby Brown and quite the celebrity. We got him to make an appearance on a Babyface video we shot in Los Angeles. Babyface also finally scored his first hit record on his own. Tender Lover, our second Babyface album, released in July 1989, was an across-the-board smash, launched by Top Ten pop hits, “Whip Appeal” and “It’s No Crime.”

Before we left Los Angeles, we had signed a group called After 7 to Virgin, although we wound up recording them in Atlanta. The group was built around two great vocalists, Melvin and Kevon Edmonds, who also happen to be Kenny’s brothers. We made a Top Twenty hit in August 1989 by After 7 with “Heat of the Moment,” a song I wrote about seducing a secretary in my office bathroom.

To get things out of the house, Kenny, our assistant Sharliss Asbury, and I rented an office space in Norcross. We hung the LaFace logo on the wall and opened for business. I dressed in a suit every morning and went to the office, feeling special about life. Everything was great, except one thing: I knew nothing about business. Outside of Uncle Rueben’s barbershop and my stint at Duro Bag, my entire life had been spent playing and making music. My business skills were nonexistent; I had never given a thought to the business side of the record business. All I knew how to do was make records. I had never worked at an office—what the fuck do they do there? One day, I dictated a letter to Sharliss and she stopped in the middle. “If you want a copy for your files,” she said, “you’re going to have to get a Xerox machine.” Step by step, we figured this stuff out and started to build an administrative staff.

A meeting at the LaFace office in Atlanta (Randall Dunn)

I never stopped to consider what I knew or didn’t know about what I was trying to do. I assumed we would figure everything out as we went along, as I always had. I had the confidence of ignorance, and what I didn’t know wasn’t going to stop me. I was running on instinct and had started a record company simply because I thought that it was the next step up the ladder.

The first act we signed was Damian Dame, a male-female duo that we moved from California to Atlanta and recorded in LaCoco. It was a good album with tracks I really liked; “Right Down to It” and a heavy rhythmic number called “Gotta Learn My Rhythm.” We took a small team to New York to present the album to Clive’s entire group. Our presentation to the Arista staff was a moment of immense pride for us. We did the entire album—the photos, the cover design, the video, everything. We had their photos blown up on poster boards. We took great pains to make sure this event went off completely professionally. This was LaFace’s first release—a celebrated moment at Arista. We played the album and the video and we left. We turned it over to Arista to do the promotion, marketing, and sales. “Exclusivity” was a big R&B chart-topper when it was released in July 1991.

Around that time, Clive asked me and Kenny to produce Whitney Houston. She was making her third album. She was undoubtedly the most popular female vocalist of the day and the biggest-selling act on the label. She had a string of number one hits, but Clive felt she needed to strengthen her grounding in contemporary black music and ease up on the pop songs. So he called LA Reid and Babyface.

Whitney flew to Atlanta and the limo service failed to pick her up. I made the forty-five-minute drive in a mad rush from Alpharetta to the airport, and I am not that good a driver under the best of circumstances. I had never met Whitney before, so I didn’t know what to expect. I was looking around the terminal for maybe a mini-entourage, maybe an assistant, when I saw a lady sitting on a bench alone in sunglasses and a scarf.

“LA?” she said

I made my apologies and whisked her off in my car, only now I was even more nervous. There was nothing in my playbook about driving around with the stars, and I was driving around in my car with Whitney Houston. I small-talked and played the radio. We hit it off instantly. We sang along to the songs on the radio together. That forty-five-minute ride felt like about five minutes.

When I got back to my house, the first thing I did was introduce her to my wife. She and Pebbles started gabbing about shoes and shopping, making that girl pop star connection immediately. We had written “I’m Your Baby Tonight” for her, and Clive found this song, “My Name Is Not Susan,” that he wanted us to produce with her. She knew the songs from the demos and had done her homework. We walked over to LaCoco, and before she stepped into the vocal booth, she stopped.

“Baby, we want to go shopping,” she said. “How long do you think before the mall closes?”

Now, “I’m Your Baby Tonight” has a lot of parts and is a bitch to sing. There was no chance she could finish her singing in the forty-five minutes before the stores closed. “I know the song,” she said. “I don’t know the bridge yet—you guys have to write the bridge—but I know the background parts and I know the lead parts. Let’s do that.”

She went into the studio, cut the lead vocal for the chorus and stacked her vocals, doubling and tripling her original vocal perfectly. Then she laid down the first track of background vocals, the second track of backgrounds, the harmony parts. We stacked them up and flew them through the track. That took her about twenty minutes. I was blown away. That voice coming through my speakers on one of Kenny’s and my songs—we’d produced a lot of records by then, but I had never heard anybody sound that good, ever. Not even close.

“Baby, I really want to go to the mall,” she said. “Let’s get to the lead vocal.”

She got behind the mic and belted that song, nailed it on the first take, right up to the bridge, which we still needed to write. “Okay, baby, give me another try,” she said.

She did it again and nailed it a second time. “Okay, what else you need?” she said.

“I guess we need to write the bridge,” I said, and off she and Pebbles went to the mall.

While they were at the mall, I went down the block to Kenny’s house and we wrote the bridge. When the girls returned from shopping, Whitney went back into the studio and polished off the bridge. Whole song, top to bottom, vocal time spent: one hour.

We finished that song and “My Name Is Not Susan.” Whitney went back to New York. We wrote a song for her called “Miracle,” and Clive wanted us to do another one he found called “Lover for Life.” Whitney came back to Atlanta one week later and she knocked out these two songs like they were nothing—pow, pow—only now we were used to it. Talk about a superpower. The girl would work to the point of exhaustion.

She came back a third time to do some fixes. Aaron had been born and Pebbles was out touring behind her new album. Whitney called from her hotel to tell me her room had been broken into and she felt uncomfortable at the hotel. Could she use the guesthouse? She showed up with her manager and running partner Robyn Crawford. It was late. I put on a movie in the theater to watch and the phone rang. It was Pebbles, who quickly became upset when she learned Whitney was there.

“Whitney’s in my house?” she said. “We’re not having that. My husband is not going to sit in my house late at night watching a movie with another girl.”

I tried to explain, but she threw a tantrum and I started to get angry. I told her she had nothing to worry about, this was completely safe, platonic, and just us musicians. I got loud and Whitney overheard.

“She’s trippin’, huh?” she said.

Whitney offered to leave, but I told her my responsibility was to take care of her and everything would be fine. “I don’t want to be in the middle of y’all’s mess,” she said.

Pebbles kept calling back and finally I took the phone off the hook. I was embarrassed. I pride myself on being a professional. I was starting a business, and was now working with—and entertaining—major celebrity superstars. I didn’t need this bullshit. Whitney went to the guesthouse to sleep.

The next day, Pebbles came home and had attitude with me. She tried having attitude with Whitney, too, but Whitney put out that fire in, like, two seconds. I don’t know what she said, but everything quickly was cool. Whitney invited us all—me, Pebbles, Babyface and his new girlfriend, Tracey (he and his wife had divorced)—to her place, so we all piled on a Delta jet and spent the weekend in New Jersey.

After I submitted the mixes, Clive sent me a five-page letter detailing what he thought was wrong. Clive is Clive and he knows what he is talking about, so you have to take it seriously, but the difficulty was understanding what he was talking about—the range and ambience surrounding her voice, stuff like that. I tried everything, but it still wasn’t right. I told Whitney to come back to Atlanta and sing it again and, this time, I made the vocal a little louder. Clive loved it. I was going through all this and he wanted the vocal more prominent. I ended up using her original vocal, only louder. Clive taught me that with a pop singer like Whitney—as opposed to the R&B ones I had been working with—you have to put the vocal way out in front. That’s her money, her sweet spot.

Whitney spent the next three days staying in the guesthouse, hanging out with my wife. I was glad to have her, but all the work was done; why was she still there? The third day, the phone rang and it was Bobby Brown.

“Whitney there?” he asked. “Let me speak to her.”

She trotted to the phone. “Hi, baby,” she said.

I had no idea that these two had a relationship. I don’t know what he said, but when she hung up the phone, she was giddy as a kid—happy, sparkling, excited. She was no longer just a shining superstar. Bobby made her a person.

“Bobby’s on his way,” she said. He showed up a half hour later in his blue Mercedes station wagon and whisked her off. The girl had been hanging around at my house for three days waiting on Bobby to call.

She had fallen in love with Bobby Brown under my roof. As I watched them ride off into the sunset, the realization sunk in. I became fascinated by this. It seemed so unlikely, but, at the same time, so right. Bobby was a street-smart bad boy and Whitney was an R&B angel. You never would have thought it, but when you saw them together, they fit like puzzle parts. They were R&B royalty.

We went from producing the regal Whitney Houston to making the next record with one of the royal family of R&B, Michael Jackson’s older brother Jermaine. While we were working on Whitney’s record, Arista had suspended the funding for LaFace because we were technically in breach of contract by not working on LaFace. It didn’t matter that Clive had been the one who asked us to work on something other than LaFace. Kenny and I had to go in pocket to cover our overhead while we worked on Whitney’s record, which left a bad taste. So when Clive asked us next to work with Jermaine Jackson, another act on Arista, we told him we would be happy to work with Jermaine, but he would have to become a LaFace artist. Clive arranged to transfer his contract.

Jermaine rented a house in Buckhead and moved to Atlanta with his family. He would come over to the house and work out with me. He wanted me to jog, eat better, to live better. I loved the guy. We started working on his album, talking with him, trying to get ideas of what he liked, writing for him. Then his brother Michael called.

Out of the blue, we received a call from Michael Jackson’s manager, who told us Michael wanted to arrange a meeting to talk about working together. This was Michael Jackson in his moment. His latest album was Bad. This was great, except what were we going to tell Jermaine? We decided to avoid it altogether, simply telling him we had a session in Los Angeles and quietly slipping away for a bit.

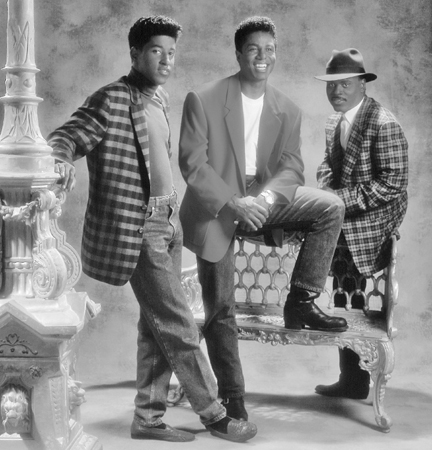

With Kenny and Jermaine Jackson, Atlanta, Georgia, 1990 (©1991, Kevin C. Rose)

A helicopter picked us up at Burbank Airport and took us to Neverland. It was a choppy ride, scary as hell. When the helicopter landed, someone drove up in a golf cart. The first thing he did was hand us confidentiality agreements to sign. Nobody got to see Michael without signing one.

We were taken to his library. The shelves were full of books about fairy tales, but the place hardly looked like a child’s house. It was done very tastefully, not like some first-year basketball player’s house with the black leather couches. We sat nervously waiting when Michael entered through a secret door behind us. “How was your flight in?” he asked.

“It was a little choppy,” I said.

“You were afraid,” he said. “I can tell. It’s in your eyes. You were afraid.” He put his hands up to his mouth, gasped, pointed at me, and started laughing.

That broke the ice. We had never met him before. We didn’t know if we were going to be meeting a weirdo or what, but right away, he was this fun-loving guy, joking around. We laughed from the first moment on. That was his way of relaxing us—pulling a joke on us—and it worked. We felt at home right away. Michael was very childlike, easy to be around. We started talking about music. He asked us what we liked. I don’t even remember what we said, but I asked him what he liked.

“I love Janet’s album,” he said. “You know that song ‘The Knowledge’?” He named four or five songs from Janet’s album, which was produced by Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis. I kept looking at Kenny, wondering why was Michael talking about Jimmy Jam and Terry’s songs to us. Does he know who we are or does he think we’re Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis?

“Those songs are great,” I said, “but we didn’t do them.”

“I know that,” he said. “You asked me what I liked. You know what I love that you guys made? ‘It’s No Crime.’ I love the drums on ‘It’s No Crime.’ I love the whole Tender Lover album, Babyface. You’re amazing.”

He liked our drum sound on one specific song? How could I have been so wrong? He knew who we were. He knew exactly who we were. Michael took us on a tour of every nook and cranny of his incredible Neverland. “You want to have some more laughs?” he said.

He took us to a screening room and ran a short clip of a James Brown concert at the Wiltern Theater in 1983, when Michael was called out of the audience and danced a few steps, mesmerizing the audience in an instant. In the clip, Jackson then whispers in Brown’s ear that Prince is also in the audience, and Brown calls him up, too, only Prince can’t make his guitar work, frantically stripping off his shirt and trying tricks with the microphone stand and making all these poses. After Michael’s dazzling star turn, Prince fell as flat as he could, and Michael enjoyed laughing at the video. After that, he put on a scene from Prince’s movie Under the Cherry Moon, the artsy, black-and-white bomb he made after Purple Rain, and he laughed some more at Prince.

He drove us in his golf cart to lunch, where his twin chefs served bowls of pasta for lunch, only Michael’s pasta was all cut in the shapes of Disney characters.

Michael didn’t want to buy a song. He wanted to pay for our time and have us work with him for three weeks. It was an unusual deal, but it appealed to us.

We went back to Atlanta to continue working with Jermaine and we didn’t say anything. Now we needed to figure out a way to get out of town for a few weeks to work with Michael after Jermaine had moved his family to Atlanta to work with us. Tucked back deep in my mind, I sensed that this could be a headache, so we decided to keep quiet. We worked with Jermaine for a couple more weeks and gave him the news that we needed to go to Los Angeles for three weeks to finish a few projects we were working on. He was cool.

Intimidated beyond belief, we sat in a couple of Los Angeles studios, trying to come up with something for Michael. But sitting there working for Michael, it was impossible to escape the idea that this was the guy who did Thriller, the biggest-selling album ever. How do you top that? How do you hope to match that kind of magnificence? It towered over us. How do you write a song he will like? At the time, Kenny and I were on a roll, but we couldn’t figure this out. Michael would come by and listen. He would like a little bit of this, a little bit of that, but nothing was blowing him away. We kept working.

He would visit. “Just keep playing me everything,” he said. “Play me music.”

He wanted our sound. We owned the charts. Our sound was the hip, cool, hot thing, and Michael wanted to use us the way he did songwriter Rod Temperton of Heatwave after he’d heard Heatwave’s “The Groove Line.” That was how Michael had made his classic breakthrough solo album, Off the Wall. We were so fascinated by him, so intimidated by his talent and stature—Michael Jackson at the absolute height of his Michael Jackson–ness—that we couldn’t get it right. We spent three weeks working night and day, so we had plenty of time to get over any initial jitters. The significance of the assignment simply overwhelmed us. We managed to put together a song called “Slave to the Rhythm” that Michael liked enough to lay down a finished vocal, and he never sang a song he didn’t believe in—he didn’t even bother to try if he didn’t.

I sat across the other side of the glass and watched in what was almost an out-of-body experience as Michael sang our song, top to bottom, twenty-four times in a row, and each take was better than the last. When he was done, I couldn’t tell track eight from track twenty-four—that’s how perfect his performance was. God was in the room and He looked just like Michael Jackson.

During another one of these sessions with Michael, I was called to the phone. I went down the hall and took the call in an office. It was Jermaine. He went crazy on me.

“I heard that you guys were in LA working on Michael’s album,” he said. “I’m sick of this. I came all the way to Atlanta to sign with your company and have you guys do my album. I hired you, and then Michael shows up and steals you. I’m sick of this guy stealing my producers. What kind of guys are you that you would even do this? I want off the label.”

I tried to reason with him a little, calm him down. Leaving the label seemed a little drastic. “No, I’m calling my lawyer,” he said. “I want off the label.” Click. Fuck.

Michael walked in. Kenny had been sitting there while I was on the phone. “What’s the problem?” asked Michael.

I told Michael that it was his brother Jermaine, who was unhappy that we had left him in Atlanta to come out to California to work on Michael’s album. “He’ll get over it,” said Michael.

“That’s not really the problem,” I said. “The problem is that he wants off the label now.”

“Did he sign a contract?” said Michael.

“Yes,” I said.

“Then he’ll have to live with it because those are the rules,” Michael said and walked out.

That Michael Jackson was one shrewd man. He was not wrong, but you didn’t expect that from Peter Pan. You expect a little compassion or something. No. Cold as ice.

We finished only the one song, “Slave to the Rhythm,” during those sessions where Michael laid down lead vocals, and it wasn’t released for another twenty-five years. We had another track nearly done, but he never finished it.

We went back to Atlanta and needed to patch up things with Jermaine. We went over to his house and apologized, explaining that it was a lifetime opportunity for us, because, after all, this was Michael Jackson, at that moment the greatest artist alive. We couldn’t turn that down. We told him we didn’t realize there was any sibling rivalry, but that we now understood how he felt and we only wanted to go back to work with him.

Jermaine was okay with it. We went back to work and what was the first thing Jermaine tells us?

“I want to make a song about my brother,” he said. “I want to talk about how he’s treated me through the years, like how every time I find producers like you guys, he takes my producers. He doesn’t care about his family or anybody but himself.”

He was the artist. We pulled out the lyric pad and drum machines and dialed up some beats. We ended up with a clever song, “Word to the Badd!!,” but we kind of lost our nerve and redid the song to make it more about Jermaine and some girl, not his brother.

We got a call from Clive. He had heard the original version and wanted to put that out.

I wasn’t proud of the record. I was ashamed. As producers and writers, we didn’t write for people; we wrote from our emotions. With Jermaine, our job was to dig into the artist’s mind and try to get his emotions on the record. We had done that, but, in this case, it was Michael Jackson we were talking about. I lost that fight. The big Los Angeles radio station Power 106 started playing the track and it caused a shit storm. Their New York City sister station Z100 jumped on it and, after that, stations across the country picked up on it. Jermaine was dissing Michael on a record—it was hot news for a second. The song was getting requested on radio. It was all over the papers.

I still kept my apartment in Los Angeles, which is where Michael reached me by phone. “You have to stop this,” he said. “You’re the head of the label. You have to kill this. This isn’t good.”

It wasn’t my fight and I wasn’t going to referee a fight between the Jackson brothers. I told him that it didn’t matter if I agreed with him, the matter was between him and his brother and I couldn’t help. Jermaine was insistent that his record be released. Apparently Michael and Jermaine held a meeting at their mother’s home at Havenhurst. I wasn’t there and I don’t know what happened, but when they came out of the meeting Jermaine called me.

“We resolved it,” he said. “The record stays out.”

Then Michael called back. “Jermaine and I had our conversation,” he said, “but I’m telling you, you really need to stop this. This is not good.”

Two days later, the record disappeared off the air, as if it had never been there in the first place. I don’t know what Michael did, I don’t know if Michael did anything, but it went away in a flash.