7

END OF THE ROAD

We had no way of knowing this back then, but LaFace arrived in Atlanta at the perfect time. New sounds were hitting the charts, as hip-hop and rap made inroads into the mainstream. The city was turning into a major metropolitan area quietly, without anyone much noticing outside the South. The new One Atlantic Center in Midtown had marked the beginning of high-rise construction that was suddenly booming. There was a fresh, vital energy that you could practically smell coming off the sidewalks. The city was brimming with possibilities. Atlanta was on the make, and the record industry wasn’t looking there. The musicians in Atlanta were hungry and we were eager to serve them.

We needed to sign our own acts, and there was no telling where we were going to find them. We didn’t really know where to look for talent or even how to look for talent, but if we were going to build our label from the ground up, we were going to have to figure those things out. We started looking everywhere and following up on every lead. The path to finding and putting together the biggest-selling girl group of all time started, of all places, in my living room.

One afternoon, my home audio specialist was lying on the floor, plugging in wires for the sound system he was installing for every room in the house, when he asked me if I knew Ali Hassan. The name meant nothing to me.

“He said he used to be a friend of yours,” he said. “They called him Dee Dee.”

Dee Dee? My best friend from junior high school, whom I’d worked on the riverboat with, was now Ali Hassan and was the sound technician’s barber. We got back in touch immediately and Ali started coming over to my house every Sunday to give me a haircut. Pebbles, who didn’t have a hairstylist in Atlanta, asked Ali one day if he knew any beauticians. He recommended a lady named Marie Davis and offered to have her come over to the house, but Pebbles said she would rather visit her shop.

While Pebbles was at the shop having Marie do her hair, she met Marie’s darling little assistant named Tionne Watkins. She told Pebbles she belonged to a group called 2nd Nature, and Pebbles invited her to bring her group over to audition.

The three girls came over—Tionne, Lisa Lopes, and Crystal Jones. Babyface, Pebbles, and I were there, as was a guitarist and friend of ours named Reggie Griffin. We went into the gym and the girls auditioned one at a time. Tionne, also called T-Boz, sang the Teddy Riley song “Wanna Get with U.” She impressed me with her tomboy look and deep masculine voice.

Then Lisa started rapping and making sound effects with her mouth. These two girls were about the same height, cute as hell. Pebbles, Babyface, and I exchanged looks. The third girl, Crystal, wasn’t as good, but we loved them, and Pebbles had already named them TLC from their first names—Tionne, Lisa, and Crystal.

About the same time, I went to a dance rehearsal for a Damian Dame video at which one of the dancers in the background kept making eye contact with me. After the rehearsal, she came up to me.

“I’m Rozonda and I can sing,” she said.

“What do you sing?” I asked.

“I sing like Anita Baker,” she said, and right there she started singing “Sweet Love” like Anita Baker. She sounded pretty good, too.

“I’ve got some people I want you to meet,” I told her. “Come with me to my house.”

I called Pebbles and told her I had just met the third member and I was bringing her over. Lisa, who was also known as Left Eye, and T-Boz, were there. Crystal was already gone. We walked in and it was like they had known each other a hundred years. I threw her in the room and left. When I came back, they had asked her to join the group and had changed her name to Chilli so they could still be TLC.

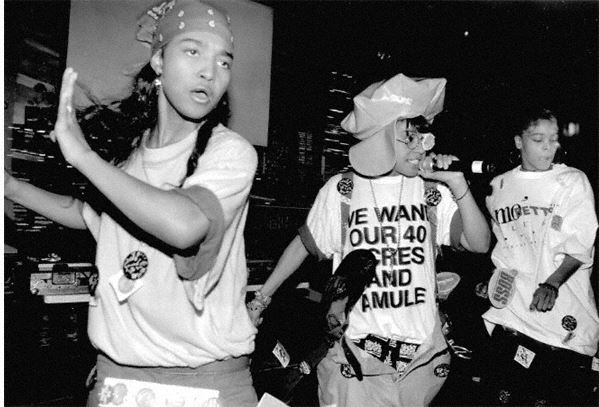

Oooh . . . on the TLC tip (Al Pereira/Getty Images)

As naturally as it came to me at the time, this was practically my first experience with discovering talent and creating recording artists. The fact that I was new at this didn’t occur to me, because I was only trying to find talent for the record label and was doing what I thought any A&R person would do.

TLC became Pebbles’s project and she swooped down on them. She didn’t have an official role at the record company, but she was the unofficial adviser on everything. She still had her own recording career, but she began to make plans to enter talent management on her own, separate from the LaFace operation. She signed TLC to her production company, Pebbitone, in February 1991. They were always spending time together at my home in the beauty salon downstairs, talking, writing, and being girls.

We took them to a concert by Bell Biv DeVoe, a group consisting of the three leading members of New Edition, where we ran into Dallas Austin. We loved Michael Bivins of Bell Biv DeVoe. They had a new style, almost hip-hop-meets-R&B. TLC was like the female version. I told Dallas I wanted him to produce the group’s album and he was all over that. What I didn’t see was that it was love at first sight for Dallas and Chilli that night.

Dallas started recording TLC while Kenny and I were in Los Angeles with Michael Jackson. When we came back three weeks later, Dallas came over to play me the TLC tapes. I don’t know what I expected, but it was like striking gold when you’re barely beginning to dig. He had “Ain’t 2 Proud 2 Beg,” which would be their smash debut release, “What about Your Friends,” and another called “His Story.” All really good. Hit records.

Halfway through the sessions for the first TLC album, Pebbles told me she was thinking of taking the girls to Giant Records, instead of signing them to LaFace. I would be damned if I was going to let TLC leave my house with my producer and my wife to sign with Giant Records. I told her that if TLC left, she could leave, too. I drew a line in the sand. It wasn’t that big a fight. She may have been only messing with my head—she liked to do that—but she signed the group to her company and we made a deal with her. The girls never actually signed to LaFace; our deal was with Pebbitone. Eventually, Kenny and I came in and did two songs for the album, “Baby-Baby-Baby” and “Shock Dat Monkey,” but Dallas was always the architect behind the TLC sound.

With those girls, there was always backstage drama. Pebbles and Chilli stopped getting along, and Pebbles, who ran the group, fired Chilli, although that is not how Pebbles remembers it. We went so far as to hold auditions for her replacement at the house, but Pebbles was out of town on tour. We looked at a cattle call of about fifty girls one afternoon and didn’t find anyone who worked, but it was a nice party. Chilli was reinstated. All this happened before the first single was even released in November 1991. The group went out as an opening act on MC Hammer’s Too Legit to Quit tour. “Ain’t 2 Proud 2 Beg” was the first of three consecutive Top Ten hits off the album, followed quickly by “Baby-Baby-Baby” and “What about Your Friends,” as TLC exploded on the scene.

TLC in concert (©ImageCollect.com/Andrea Renault/Glob Photos, Inc.)

TLC wasn’t simple pop—it was edgy, dangerous, and daring music coming from unapologetically emancipated females. They were young, sexy women, but they turned the tables on male stereotypes. They took B-boy style and made it their own. Their influences were men more than women. The lyrics that Dallas wrote came from a female point of view, but they were about power and superiority; the girls were never victims. A lot of thought went into this by the people making those records, and the group struck a huge cultural chord. They were so profemale they became heroes to their audience.

TLC was only the beginning. That same month I signed TLC, a man who worked for Clive called about a group the label had signed called the Braxtons that Clive was dropping. “I think you and Kenny should see them,” he said.

They were five sisters—Traci, Tamar, Trina, Towanda, and Toni. They came to Atlanta and we auditioned them at one of the local nightclubs. When the girl on piano started to sing, Kenny and I looked at each other. We knew that was a special voice. She sang in a lower register, almost an alto, but I sensed something more in her. We told them we wanted to sign the group, but we really only wanted the piano player, Toni. As we worked out the contract later with their manager, I told him we really only wanted the one, and we wanted to offer her a deal with LaFace Records.

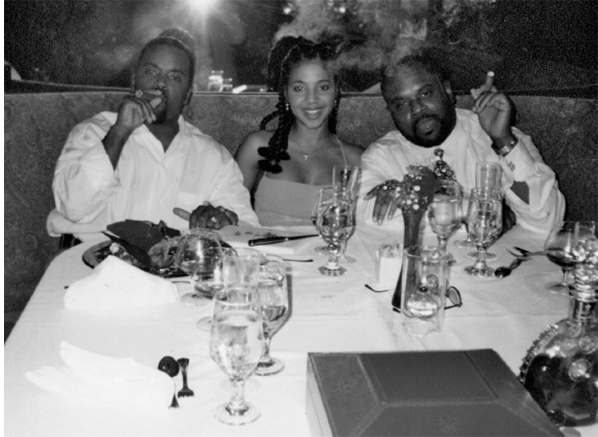

At dinner with Toni and my brother, Bryant, Miami Beach

Toni now had to decide whether to take the contract or stay with her sisters. For years, I didn’t know this, but it turned out that her mother went crazy on her—How dare you leave your sisters? They are your sisters. You’ve been singing together your whole lives. You go to Atlanta and these men want to separate you. And you want to do it? How dare you? She made Toni feel terrible about it, but Toni signed as a solo performer with LaFace Records.

We made these two signings in February 1991, but the label still hadn’t made a true hit. In the eighteen months since we had moved to Atlanta, we had made big records with Pebbles, Babyface, Johnny Gill, Bobby Brown, and Whitney Houston, but they were all for other labels. We were recording the first TLC album, and we thought Toni Braxton could be something. But it was up to me to get the label going. Kenny was mainly involved in composing and recording. I was in charge of running the day-to-day affairs of the company. The label was my dream, not necessarily Kenny’s.

I needed a breakthrough strategy. It kind of started with a dinner I had with Toni Braxton and her manager at a restaurant called Pricci in Atlanta a couple of weeks after we signed her. The manager asked me what my plans were for Toni. I didn’t have any plans, but I started talking, and pretty much on the spot, I devised a plan: We would go find a movie soundtrack that would feature Toni Braxton. That would be the launching pad for her career, and then we’d make her album. They loved the idea. I had no idea where I came up with it. We finished a lovely dinner, said goodnight, and I never thought about it again.

A few months later, I had still forgotten all about what I told Toni and her manager when I called Cassandra Mills, who worked with Irving Azoff, to ask how could I get a soundtrack deal. She told me Eddie Murphy was making a movie called Boomerang to be directed by the Hudlin brothers, Reginald and Warrington Hudlin, premier black film directors.

“You should call them,” she said. “They’ll take your call. They know who you are. Tell them that you want that soundtrack. It’s perfect for you.”

I reached out to them and they invited me to New York City. I flew up by myself and went to meet them at a screening of the Tupac Shakur film Juice. I met Diana Ross at the screening, as I hung around the lobby after the movie trying to meet up, but I didn’t know what either of the Hudlin brothers looked like. I asked Andre Harrell, who had his own label, Uptown Records, and whom I had chatted with before the movie. “That’s Warrington over there,” he said, pointing.

We arranged a meeting for the next day. They told me that the movie was about to start production, a romantic comedy starring Eddie Murphy, Halle Berry, and Martin Lawrence. They were receptive, but had reservations about LaFace and wanted me to arrange a meeting with Arista to make sure we had their support. It took a while to reach Clive—he was attending some convention—but he agreed. I set up the meet at the ultrahip Royalton Hotel, and when Clive assured the Hudlins that Arista Records would back the play, we landed the deal.

With the First Lady of LaFace, Toni Braxton

Kenny and I came up with a wish list for the soundtrack, and at the top of the list was Anita Baker. Not only was she the coolest new singer on the scene, but her demographic fit perfectly with that of the movie. We watched the dailies in New York and would take notes. In this one scene, Halle Berry turned to Eddie Murphy and said, “Love—what do you know about love? Love should have brought your ass home last night.”

Kenny and I traded that knowing look.

We went back to Atlanta and started writing songs. We picked up another piece of dialogue—“There you go again”—and wrote “There U Go” for Johnny Gill. We wrote four songs that we thought would be perfect for Anita Baker, including “Love Shoulda Brought You Home.” We asked Toni Braxton to sing the demos.

We wrote another song, “End of the Road,” which Kenny sang on the demo, and sent them to the Hudlins and Anita Baker. I got a call back from her.

“These songs are really good, but they’re not for me,” she said.

My heart sank. “We wrote the songs specifically for you,” I said. She didn’t budge.

“I believe you,” she said, “but it’s just not for me. I don’t want to offend you guys, but I’m going to have to say no.”

Devastated, I called Reginald Hudlin and told him Anita turned us down. “Well, who’s the girl singing on the demo?” he said. “Let’s keep her. She sounds great.”

We kept Toni on the record. Her vocals were perfect—nobody missed Anita Baker—but we gave one of the songs, “End of the Road,” to a hot boy band out of Philly called Boyz II Men.

When I showed up at the writing session that produced “End of the Road,” in a little hideaway house we kept in Buckhead near Kenny’s apartment, Kenny and Daryl Simmons had already finished about 90 percent of the song, but there was this one little part that needed filling out, a space in the lyric that was missing. I walked in and filled the part. If I hadn’t showed up when I did, they would have filled it without me. It was another song we wrote after watching the dailies, writing songs for specific scenes. Kenny, Daryl, Kayo, and I cut the demo at LaCoco and played the finished demo for the manager of Boys II Men, four teens who were riding high with a big hit record, “Motownphilly,” by Dallas Austin.

Kenny, Daryl, and I flew to Philly and met the guys in the studio at about eleven in the morning on a Sunday. It was one of those memorable days that live in your mind forever. We started by recording their background vocals, all four of the guys at one time. We spread the background parts throughout the track, and it was time to cut lead vocals. First up was Nate Morris, always the guy who started their songs, and when he opened his mouth to sing the first verse, what came out was gold. The song had sounded good with Kenny singing on the demo, but Nate transformed the song in the first bars.

Shawn Stockman took his place behind the mic to sing the second verse. “Do you mind if I play with this a little bit rather than singing exactly the way Kenny sang it on the demo?” he asked.

I told him to go for it, and, as he slid into Kenny’s melody, he massaged it, squeezed it, manicured it, and gave that verse a whole new sound. That hadn’t happened much with us, somebody singing something that differently from the demo, but when Boyz II Men sang the song, they found their own beauty in it.

When we got to the bridge, Wanya Morris, their take-it-home singer, took everything to church. “This time instead / Just come to my bed / And baby just don’t let me go.”

We staggered out of the studio in Philly around five in the afternoon and flew back to Atlanta, where I stayed up all night with our engineer Barney Perkins at LaCoco mixing the song. My trainer showed up at eight o’clock Monday morning for my workout and I was still in the studio when he found me.

“Do me a favor,” I said. “Can you clap on the beat?”

The two of us went into the booth and laid down about four tracks of handclaps. Barney and I mixed the ending so that we faded down the instrumental track and left Boyz II Men singing the chorus, Wanya wailing over the top, and the only thing you can hear is the handclaps by my trainer and me.

As much as I liked the song, I didn’t truly know how good it was until Clive Davis came to Atlanta to listen to music and I played him four or five things, including “End of the Road.” I saw him and his number two guy exchange a look when that song played. I hadn’t seen that look before, but I knew immediately that it was the look of a hit. He had seen God in the room. You know when that’s it.

“That song right there, ‘End of the Road,’” Clive said, “that’s a very special song.”

We used all our relationships for the Boomerang soundtrack. We got Johnny Gill to do “There U Go.” We gave a song to Keith Washington. Grace Jones was in the movie, so we asked Dallas Austin to write a song for her and he came up with “7 Day Weekend.” We flew her in to record. She had demands up to here and we needed to put one of our girls on her case full-time to make sure she got everything she needed. We found this group called PM Dawn who gave us a great song, “I’d Die Without You,” and we got “Hot Sex” from hip-hop legends A Tribe Called Quest. We finished the album and the Hudlins cut the songs into the movie. The first single was “Give U My Heart” by Babyface and Toni Braxton, the closing-title love song that was supposed to have been a duet between ’Face and Anita Baker in June 1992.

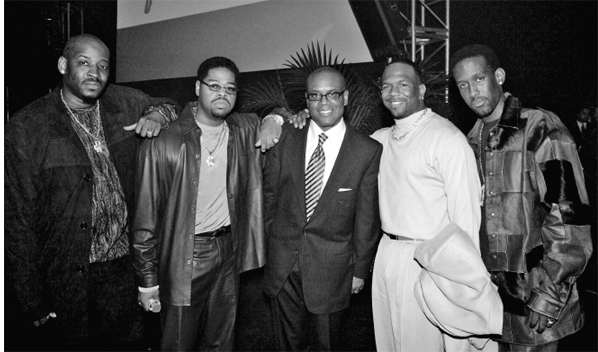

If you hear any noize, it’s just me and the Boyz II Men. (KMazur/Getty Images)

The record started to catch steam and turned into a hit. Next up, we put out “End of the Road,” and it skyrocketed. The damn record held down the number one spot for thirteen weeks, breaking a record set thirty-six years earlier by Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog/Don’t Be Cruel.” “End of the Road” won two Grammys the next year. The third single, “Love Shoulda Brought You Home” was the best of the bunch, and it instantly established Toni Braxton. Her new album was anticipated and her career was launched, just as I told her it would be.

The Boomerang soundtrack sold more than three million copies. The first TLC album, Ooooooohhh . . . On the TLC Tip, did more than two and a half million albums. Now LaFace was established, too. With the successes of Boomerang, TLC, Toni, and Babyface, everything was coming together—Atlanta, LaFace, the music scene. We were in a town that couldn’t feel the pulse of the music industry. It wasn’t a media center like Hollywood or New York. We were successful, but we couldn’t feel it. Not only did we establish LaFace, we put Atlanta on the music map.