chickens

Chickens, simply going about their daily business, are capable of altering any landscape into one of peaceful serenity.

No farm animal typifies the country-living experience better than a chicken. A few scattered hens lazily picking through the grass, a rooster strutting along the fence rail, or the whole lot scurrying to the child who calls them in for grain—their very presence on the landscape stirs the romanticism of simpler times.

Psychological effects aside, the rewards of keeping chickens are numerous. They’ll bless your home with the finest quality, the tastiest, and the healthiest eggs and poultry you have ever consumed.

Since early domestication, this is the way chicken and eggs were meant to be enjoyed. Your taste buds will be challenged to be satisfied with the grocer’s version ever again.

Knowing that the food at home is superior in all regards, you may soon find yourself turning up your nose at restaurant and take-out meals.

Chickens are also an easy, inexpensive keep. Provided that you already have a small shed, you could be enjoying fresh eggs just a few days from now.

If I had but four sentences to describe the joy of keeping chickens they would be: “Cheap to purchase and to feed. Don’t require much in way of housing. A few minutes per day to care for. Blessings unnumbered as reward.” Where else can you get so much for so little?

Energy-Efficient Poultry

It takes:

Twenty pounds of feed to produce one pound of beef.

Three and one half pounds of feed to produce one pound of protein from eggs*.

Two pounds of feed to produce one pound of chicken.

* The average large egg contains 0.7 pounds of protein.

A Healthier Alternative for Your Family

Purchasing poultry and eggs at your local grocery store is a budget-friendly way to feed your family. Compared to an unknown risk—that raising chickens at home might cost more—you may wonder if the added responsibility is worth all the bother. Setting economics and household budgets aside for later discussion, I assure you that raising your own eggs and poultry is definitely worth the bother. What you don’t pay for today at the grocery store, you may be paying for in the future with your health.

Commercially raised poultry and eggs are reasonably priced due to the volume and efficiency of chicken factories in North America. With highly efficient systems and rigorous demands, these factories have mastered the art of maximum output with minimal waste of labor, space, and feed. Although it may be admirable on the surface (their efficiency facilitates lower grocery bill totals for families), you can’t help but wonder, “At what real cost?”

• Less flavor, nutrition, and freshness.

• Potentially more chemicals, residual antibiotics, unnatural hormones and additives to the end product.

• Our consumption of animals that have led miserable lives.

This is what we have been feeding, for the most part unaware, to our families, the effects and health risks of which are yet to be fully discovered.

Until now.

In the last fifteen years, there has been no escaping monthly news reports across the continent, health articles around the world, and feature film documentaries on the implications of production-raised poultry. Large-scale poultry growers and egg factories are fined or shut down regularly for unsanitary, inhumane, and unethical practices. Many more continue to operate unnoticed. Neither blowing the whistle nor passing judgment on every packing house or poultry factory, the following growing practices are more common in North America than we know.

Red sex-link hens, confined from the age of twenty weeks, spend their lives eating and producing eggs in harsh conditions.

• Meat birds are being fed hormones for fast growth. To deal with unsanitary conditions and stress-related sickness brought on from overcrowding, they are also fed a steady diet of antibiotic-laden feed.

• Laying hens are restricted to cages barely larger than their own bodies, in rooms where lights are left on for twenty-four hours a day, fed production-inducing and antibiotic-laden feed, and then culled the very day they stop laying.

These are possibly the only avenues poultry and egg factory farms have to feed a hungry, budget-conscious nation while still turning a profit. Yet our increasing awareness of these practices make inexpensive eggs and poultry seem less a bargain in the checkout line.

There is a better way.

Growing your own chicken and keeping laying hens buys you peace of mind. You know precisely the quality of the nourishment you are setting upon your dinner table, the humane manner in which that animal has been raised, and who you are supporting through purchase.

The Challenges of Chickens

Raising your own poultry is personally satisfying, but the journey from chick to table will have a few challenges along the way.

Although the positive aspects outweigh the negative, three common annoyances are dust, smell, and noise. The latter two are easily controlled. Dust, however, is inescapable.

Even a flock of ten chickens can create a considerable amount of dust through their litter and dander. This, plus the possibility of disease or virus transfer to other farm animals, is the primary reason poultry should have their own shelter.

A substantial portion of your coop chores will be based on dust removal. As long as the chickens are self-contained and healthy, it is your personal choice either to manage it regularly or to delegate the task to a larger, quarterly cleaning. As you’ve protected other farm animals from poultry dust, don’t neglect yourself during coop cleaning. Wear a surgical mask, or even a kerchief over your nose and mouth, to avoid inhalation of the fine dust. Lung health implications of poultry dust are well-documented as cumulative.

To keep all animals on your farm protected, chickens should have their own shelter.

The final two challenges, smell and noise, are often neighborly complaints. Sharing your farm-fresh eggs across the fence will go a long way to keeping the peace. If your coop is located on a shared property line, add a little extra litter to dramatically reduce coop odors, and avert potential noise complaints by opting out of keeping a rooster. A rooster’s crow begins at the very first show of light, continues throughout the day, and can carry for a mile or more. Unless you are planning on breeding your laying hens and hatching out chicks, the rooster is nothing more than pretty plumage.

Knowing your objective for raising chickens is the first step to selecting a breed that is right for you. While some breeds have been developed for maximum egg production, others excel at quick growth and efficient feed conversion. Chicken breeds are therefore classified as egg layers, meat birds, or dual-purpose. A final class, the exhibition breeds, are beautiful and useful but are not considered top producers for home farms. For your time, space, and money, the first three classifications provide the highest return on investment.

The list of chicken breeds to choose from is extensive. On GoodByeCityLife.com I maintain an ever-growing list of over one hundred known breeds, and I have only scratched the surface. All reputable hatcheries produce catalogs of the most popular breeds for your region, as well as a few fancy and hatchery-developed hybrids. Within each description you’ll discover the hardiness, expected size, and production rates of each breed offered.

CHICKEN FUNDAMENTALS

Although a few breeds’ needs vary in particularity, chickens all require three commonalities in care:

• A commitment to a chore schedule that keeps their coop and equipment clean.

• Access to fresh water and feed at all times.

• Safety from disease, weather extremes, and predators.

Egg Layers

The egg-laying breeds have been developed to provide maximum egg output from the smallest feed intake. Although the hens of these breeds perform best in the controlled environments of large-scale farming, their small-farm use is popular with families looking only for a supply of fresh eggs. Supplementary heat and lighting ensures healthy hens provide a steady supply of eggs in regions where temperatures drop below 60 degrees Fahrenheit.

Should you choose production over personality, the White Leghorn is considered a top layer in her class. These hens are high strung and seldom bond with their keepers, but their feed-to-egg ability is unmatched.

Hens in this class will lay six to seven eggs per week for two years. By their third year, output is decreased to 50 percent or less and the hens are considered spent. Hens are small and the meat can be tough but may be sufficient to flavor a small soup.

The Productive Life of a Laying Hen

A pullet (female chicken) will have eaten twenty-five pounds of feed before she begins laying at twenty to twenty-four weeks.

At thirty weeks she will produce a standard-size egg almost daily.

At seventy-five weeks of age she will go through a molting period (replacing old feathers with new) for approximately eight weeks. During the molt she may not produce at all.

In her first laying year she will supply about twenty dozen eggs. In her second year her eggs will be larger but production will decrease to sixteen to eighteen dozen eggs per year. By the third year she is considered a spent hen and may only lay one egg every three to four days.

Meat Breeds

Very few North Americans raise a pure meat breed for the freezer, opting instead to raise a faster-growing cross. The most popular and easy-to-grow cross is that of a Cornish game (a true meat breed) with the Plymouth Rock (a dual-purpose breed) for its excellence in feed-to-meat conversion. A good cross will eat two pounds of feed for every pound of weight gained. By nine weeks of age the conversion ratio begins to deteriorate.

The drawback to growing these crosses is that they can neither be bred nor kept long-term. Each time you need to replenish your freezer’s supply of poultry you’ll be back at the hatchery placing another order.

It is in this class you will find the breeds that fulfill the romanticism of country life, as well as the needs of a small farm or homestead. All dual-purpose breeds produce and grow at similar rates, have interesting personalities, and are easily trained. If your goal is to become self-sufficient, you could order a rooster to match your hens and eliminate future hatchery orders.

Early American settlers developed the most common of these breeds, producing weather-hardy laying hens and cockerels that grow to broiler size.

Although not as efficient at feed conversion as a meat breed cross, the dual-purpose cockerel finishes as a delicious three-pound meal for your dinner table by eighteen weeks. The hens, most of which you’ll keep for two years, produce 75 to 80 percent of a dedicated egg-laying breed’s volume.

The oldest and most popular breeds in this class are the Plymouth Rock, the Rhode Island Red, the Delaware, and the New Hampshire. Hatchery-specific hybrids and crosses are also popular in this class and are offered under a variety of names. As an example the common Red Sex Link or Red Star (or any other name a hatchery deems marketable) is created by breeding a dual-purpose Rhode Island Red rooster to a laying-breed Leghorn hen. The resulting hens are hardier than the Leghorn and have a higher egg production than the pure Rhode Island Red. The resulting cockerels, however, have a slightly smaller finishing weight than a pure Rhode Island Red.

The Barred Plymouth Rock, developed in America. A proficient dual-purpose layer that also grows to broiler size by twenty weeks of age.

Chicken Instinct and Temperament

Chickens, an easy keep and simple in needs, have quirks and instinctual oddities all their own. They’ll make you laugh, contemplate the human complexity of life, and frustrate you all at the same time with their actions and antics.

Whether you want to train your chickens to come running when you call, break bad habits, or understand and work within the scope of their quirks, you’ll need to understand their instincts and motivations.

Social Order in Flocks

Chickens have a highly developed social order. Starting with the rooster or lead hen and organized down to the weakest chick, every flock member has its place.

Chickens raised together will have established the flock’s social order by three weeks of age.

Social order is maintained through pecking. The top hen can peck everyone, and the second hen can peck everyone except for the top hen, all the way down the line until the very last hen. She is pecked by all but cannot peck back. If you watch closely you can note which of your hens are lowest in the chain.

Whenever you introduce a new hen to the flock, the social order is disturbed. The resulting aggression is worthy of concern. Existing flocks have been known to kill a new hen in their effort to “put her in her place.” New hens need slow introductions into established flocks. A fence between them for a week or two helps make the transition smoother. As an extra precaution, introduce the new hen to the others one at a time, beginning with the lowest in the pecking order.

Cocks are always prone to a hearty scrap, even after they seem to have reached an understanding. If they have accepted their places and established their own flocks of hens and feed stations, the need to squabble is lessened. Some cocks are more aggressive than others and may never accept another male in their vicinity.

Cannibalism and Feather Picking

The worst pecking habit is cannibalism. In the brooding box and under bright heat lamps, chicks begin to feather out. Their brood mates, noticing the new small specks appearing, peck at each other. Pecking escalates, one weaker chick is picked on, and eventually the entire flock is in on the action.

These chickens are, for the most part, bored. With exercise and a red heat lamp (red minimizes the show of new feathers), you can prevent this altogether. Provide low perches at various heights for one- to four-week-old chicks to keep them physically occupied.

Feather picking is similar to cannibalism. Hens will pull on their own feathers as well as others in the flock. Although it can be prevented with a beak trim at sixteen to twenty weeks, it is more important to determine the cause. Improper feed, unbalanced nutrients in the feed, bright lights for too many hours, poor ventilation in the coop, overcrowding, boredom, and parasitic infestation are all known causes of feather picking.

Egg Eating

Laying hens, coming of age, commonly drop their first eggs on the floor on their way to the nesting box. The egg may crack or the other hens may peck at the egg. Chickens find eggs tasty and as soon as this happens, the egg-eating habit has begun—not even eggs laid in the nest will be safe.

Knowledge serves prevention. Watch coming-of-age layers and never leave an egg on the floor—even if it’s soiled and your hands are full. If you have many hens laying their eggs on the floor, check the dimensions and accessibility of the nesting boxes you’ve provided.

Training Chickens to Come

Chickens, like most any other animals, can be trained through food reward. Scratch grain is easily accessible. My hens’ favorite treats are cheese and cantaloupe. When you’re training chickens to come, use a key word or sound to trigger a treat or you’ll have them rushing to you at every sighting.

Training takes no time at all and could save a chicken’s life if you need to get him back to the coop in a hurry. For a few consecutive days, while they’re all going about their business, start calling them with your trigger word and drop a little scratch grain on clean, dry ground. A few will come over to investigate. Flock mentality will soon have them all around your feet. Keep using the trigger word and keep dropping grain for four to five minutes. That’s all there is to it.

The Need to Brood

The Little Red Hen’s Gosling

A few years ago my mother goose repeatedly, systematically, and daily, rolled one egg out of her nest. I kept putting it back. She kept rolling it out. I could have taken it as a sign of natural selection. Instead I tucked the goose egg under a laying hen already nesting on her own eggs. The goose egg took longer than the others beneath her, but my Rhode Island Red hen still hatched and later mothered her gosling.

A hen’s natural instinct is to lay a clutch of eggs, then sit on and hatch them. Yet every day you enter the coop and remove her egg, effectively returning her to day one of the process. If she has a very strong desire to brood, she might sit on and defend any egg she finds in the nest.

Roosters live their lives in blissful ignorance of their owner’s need to sleep in undisturbed on the weekends.

Although noble and invaluable to the small flock owner desiring to increase flock size, the broody and protective trait isn’t acceptable when eggs are required daily. The term “to break up a broody” and suggested practices to prevent broodiness (confinement, wire cages left in drafty locations, denial of access to feed and water) are cruel and unnecessary. Broody hens have already gone off their food. Denying access completely will result in liver damage and other complications.

The best practice is to slip on a glove and keep removing the eggs from underneath her. In her own time she will stop trying to fight you for those eggs.

Quieting a Rooster’s Crows

The domestic chicken has inherited and kept most of the traits of its wild ancestors. Roosters are a flock’s only natural protection. Their crowing, carried on not just in the morning but throughout the entire day, is a territorial warning. You cannot retrain instinct. Accommodations must be made. Although roosters are unnecessary if you don’t plan on breeding your hens, many people enjoy their look, their ability to protect the flock, and their wake-up call. Melodious as it may be to you, your neighbors might not be as impressed at 4 A.M. on a Sunday morning.

Outwitting his instinctual nature is an option, but I would suggest that the following methods are neither easy nor entirely effective. Consider giving him away or, if he’s young enough, dress him for your freezer.

Crowing is instinctual behavior. This is the rooster’s means of protecting and maintaining his flock of hens—his very purpose in life. It can neither be untaught nor discouraged by any means. Surgery is possible, but expensive and inhumane.

To crow, a rooster must stand up tall and crane his neck upward. If you can prevent him from a full stretch, you might be able to quiet his earliest morning crows. This involves catching him every night and bedding him down in a cage that is too short for him to stretch. If you take this route every night while you look for a new home for him, be sure to release him as soon as you awake. It isn’t fair to an animal to be awake, instinctively driven to crow, and immobilized.

A more humane short-term option might be to section off a dark corner of the coop and chase him in every night. Your goal is to trick him into believing it is still night until you release him in the morning. If he hears his hens stirring in the morning he may start crowing anyway. At the very least he will be stressed.

Designing Your Small Farm Strategy

After years of switching between various breeds—often raising two classes at a time—I have once again returned to keeping Barred Plymouth Rocks, a dual-purpose breed. My reasons for doing so are based on our family’s needs, climate conditions, and available space (both in the coop and in the freezer). Your needs will vary from mine and, as your personal requirements change, over time. To help you determine your best strategy from year to year, here are some of the top considerations before placing your hatchery order.

Meat Birds

• Grow meat birds to whatever size fits your family best. As an example, a family of four that doesn’t enjoy leftovers might opt to grow their broilers to a three-pound dressed weight in seven weeks.

• Check your calendar before you order. If you will be butchering the chickens yourself you’ll need a few days open for the task seven to nine weeks from the date day-old chicks arrive, or five to seven weeks from the date started chicks arrive. You don’t want to overgrow a meat breed when their conversion rates drop. You’ll be losing money—potentially losing lives. Past the weight of seven to eight pounds (live weight) feed-to-muscle conversion slows. In my experience, almost all growth over nine pounds (live weight) is stored as fat that just ends up in the garbage bin anyway. Growing to obesity also wreaks havoc on your meat birds’ overall health. Obese hybrids have an added sensitivity to heat and are prone to heart attacks.

• Five or six laying hens at peak production will lay between two and three dozen eggs per week—an ample quantity for the average family of four. Add extra hens to your order and you’ll always have an extra dozen to share with (or sell to) friends, family, and neighbors.

• Replace laying hens every two years. Productivity will be dramatically reduced by the third year. Even the hyper-productive Leghorn drops down to one egg every three days at this age.

Timing

• Plan on a spring start and you will move into the fall season with a freezer full of chicken meat and hardy hens laying in the coop.

• Starting with day-olds? You can raise meat birds and laying hens in one partitioned coop. By the time the layers need the space the meat birds will already be in the freezer.

• Dual-purpose cockerels take eighteen to twenty weeks to reach full size; hens take twenty-five to start laying.

Freezer Space

• If your family eats one chicken dinner per week you’ll be raising over fifty meat birds throughout the year. Consider the option of raising two sets of twenty-five for fresher poultry throughout the year if your climate permits. Consider owning two smaller freezers and emptying out one halfway through the year to conserve energy.

Ordering

• Some hatcheries will let you specify your order to contain all male (cockerels) or a mix of both sexes. A little more expensive per chick, the males will grow faster and make better use of their food intake. If you grow only cockerels you will have yet one more reason to be committed to your finish date. Cornish-cross cocks—like any other breed—will squabble and crow at maturity. Ensure you get them to the freezer on time and you shouldn’t have any problems with coop fights or crowing complaints.

• All breeds will consume more food during cooler months.

• All breeds need supplementary heat if temperatures drop below 60 degrees Fahrenheit.

• Don’t buy or keep a dual-purpose or laying-breed rooster if you don’t plan on hatching chicks.

• A laying hen eats twenty-five pounds of grain before she’ll lay her first egg. Consider buying started pullets or ready-to-lay hens.

• Running heat lamps, supplementary winter lighting, and coop heaters increases the cost of raising poultry. Minimize coop space for wintered chickens, add insulation, and keep the area draft-free to cut down costs.

The Chicken Coop and Yard

Although you will need to provide a shelter for your chickens, it merely needs to be adequate—adequate protection from extreme temperature and from predators, adequate space to eliminate stress-related illnesses from cramped living quarters, and adequate containment from your personal property and other farm animals’ feed.

A shed or a corner of an existing barn will be sufficient. If you must build a coop, the simplest to build is a square building with:

• A slanted roof (rain should run away from the yard)

• Two doors, one for you and one for the chickens

• A ceiling tall enough that you can stand easily inside

• Enough space for the quantity of chickens you desire, plus room to add a few more along the way

Building a Stationary Chicken Coop?

Build it on a slight slope to prevent muddy yards during the rainy seasons.

Build it close enough to a stand of trees to reduce the chilling effect of winter’s prevailing winds. At the same time, build it far enough away from the stand of trees to ensure that predators cannot jump from trees to the outside yard.

Have your coop wired for electricity or add in a few solar panels. A heat lamp for new chicks, extra light during the winter for laying hens, and/or a small heater for the coldest nights of the year are practical necessities.

How Much Space?

Recommended space for a full-grown chicken is two to two and a half square feet—quite likely twice as much space as a chicken would receive in a poultry factory. Of the belief that a little more is a lot better, I allot four square feet each. This extra space means less concentration of odor, fewer fights among the flock, a lot less stress for the birds, and more places for you to put your feet when visiting the coop.

Based on my four-square-feet rule, twenty-five chickens of any breed can be housed in a ten-foot by ten-foot (one-hundred-square-foot) space. Add an outdoor run of another four hundred square feet (sixteen square feet each) and your chickens will have ample room to grow, explore, and exercise with few problems.

I apply the same principle when raising meat birds. Old-school farmers and hatcheries state that meat birds don’t require as much room nor do they need an outside run. Their theory is that exercising the meat bird wastes feed energy that could be better utilized for building bulk. Although true—that a meat bird’s sole purpose is to grow and therefore it does not need outdoor space—fresh air, sunshine, and space enhance their quality of life. When contemplating the blessings these birds give my family, a little extra feed and a little extra space just seems fair.

A backyard chicken tractor. Note the handles (for moving) and ventilation holes above the roosting and nesting area on the “top” floor.

Variations of Coops

In the last ten years, one type of chicken housing has been growing in popularity in both urban and country yards. Dubbed the “chicken tractor,” these movable coops are made to house four to six chickens comfortably. Tops are hinged to make egg collection, feeding, and water changes a snap. Coop mobility ensures no one area of the yard is compromised and chickens are less likely to develop internal parasitic infestations as a result.

Litter

Spread litter on the floor of your coop and within nesting boxes to absorb smell and feces. Depending on your coop floor and the season, extra litter might also provide insulation. Begin a freshly cleaned coop with four inches of litter, adding an inch of fresh litter when the litter has lost its ability to absorb smell, becomes trampled down, or is noticeably soiled. Completely replace litter during every major cleaning.

Litter can be any soft and absorbent material, such as straw, ground-up corncobs, wood chips and shavings, or shredded paper. Use whichever you can purchase inexpensively and is accessible nearby. Your local feed store might provide leads on sawmills that sell shavings or farmers who sell straw.

Temperature Control

The optimum temperature for chickens is between 45 and 80 degrees Fahrenheit. Extremes on either side may result in less-efficient conversion of feed. Temperature-related troubles include: fewer or smaller eggs, slower-growing meat birds, thin-shelled eggs, frostbitten combs and feet, onset of stress-related sickness, and death.

In cooler climates your coop should be completely free of drafts. Add a heat lamp or small heater over the roosting area when temperatures dip below 45 degrees Fahrenheit. Keep in mind that litter could be a fire hazard if kicked onto a floor-based heat source.

Be innovative in conserving electricity when wintering hens. In previous years I have moved laying hens to a smaller shed and have also been known to drop the ceiling on my large coop with securely stapled tarps and Styrofoam insulation above. In northern climates some people will move their hens to a south-facing front or back porch during winter months.

When temperatures climb into the high 70s, air will need to move freely and regularly through the coop. Wire-screened windows in the coop allow for cross breezes as do wire mesh gable ends or vents close to floor level (create sliders or board them over for winter).

Chickens require shade, extra water, and cross-ventilation during summer. Sliding mesh vents, such as the ones shown in this photo, ensure that air moves freely inside.

Coop Cleanliness

Keeping your coop clean serves a dual purpose—your chickens remain healthy and odors are controlled. If you save coop-cleaning chores to once per week, other obligations will almost always take you away. On the other hand, regular maintenance in your twice-daily visits will result in a coop kept nearly as clean as the day your chickens arrived.

Daily chores include checking chickens’ dishes, collecting eggs (if raising layers), and opening or closing yard access. Take just a few minutes, every now and then, to add new litter, sweep dust off rafters and walls, change nesting materials, or remove wet litter from the base of watering stations. You’ll now have your weekends free to enjoy your chickens from the back porch with your feet up.

A few minutes here and there, a complete litter change every four to eight weeks (depending on odor), and a clean-and-disinfect session once to twice per year is all that is required to have happy chickens with a coop you’ll be proud to show off.

Coop Equipment

Equipment to outfit your chicken coop is minimal. You’ll need food and water containers and, if raising laying hens, perches and nesting boxes.

Roosters and hens are instinctively territorial, and feeding stations are within the dominion of territory. Although it may seem excessive, provide two watering and feeding stations per twenty-five chickens. The extra feeders and founts are a preventative measure that ensures every bird has access to food and water without stress. This measure of prevention turns to necessity should you introduce new birds to an existing flock or if you own more than one rooster in a large flock.

Founts

Chickens need access to water at all times and will consume one to two cups of water per day each.

Daily consumption varies per bird and across the seasons. A laying hen can drink twice as much as a meat bird of equal size.

During hot summer days your chickens can drink up to twice as much water as usual to keep their body temperature manageable. I like to add an extra fount in a shady spot of their yard to ensure they have quick and easy access to water at all times. In the winter an electric or solar powered de-icer saves you six trips to the coop to ensure your hens stay hydrated.

An inexpensive galvanized fount can last you many years. They are easy to handle, are quickly disinfected with a mild bleach solution, and should they ever crack, a quick bead of epoxy repairs them. If you keep founts elevated you’ll prevent waste from collecting in the trough area and rust from ruining the base.

I’ve never been fond of plastic as a long-term solution, but the small plastic founts are perfect when you need to quarantine a hen or when you are starting young chicks. Keep larger plastic founts out of direct sunlight and do not use if a chance of freezing exists. Plastic founts are prone to crack in extremes and may leach toxins into the water if not made of BPA-free plastic.

Galvanized watering founts are priced to fit your budget and last for many years.

Dirty watering stations are a breeding ground for bacteria. Changing the water daily and sanitizing the fount weekly are as important as having an ample supply. Chickens are notorious for drinking with food in their mouths and kicking litter into the trough. Alleviate both problems by moving founts away from feeders and raising them off the floor to the chickens’ chest level.

Feeders

As with water, chickens need to eat all day long to stay healthy and remain free of stress.

The rule of thumb is one five-gallon feeder for every twenty-five chickens plus one extra for every rooster in the coop. Even if you don’t have two roosters, keep two feeders in operation to ensure chickens lower in the pecking order don’t go hungry.

The base of this feeder has a curved side and a rolled rim, lessening the amount of food wasted by chickens billing out their feed.

Chickens have no respect for household economics and are notorious for picking through feed for choice bits, dumping out and wasting a huge amount of feed. If you adjust the height of the feed basin to match their chest level and purchase a feeder with a rim that rolls inward, you can prevent the costly habit known as billing out. Hanging feeders allow you to make height adjustments as your chickens grow.

Another wasteful but preventable habit is when chickens roost upon the feeder top and soil the feed within. Hanging feeders deter them, but if they persist, add more roosting space in your coop and cut an upturned plastic bucket for a custom-fit cover.

Supplement Feeders

All chickens store and use grit in their gizzards to grind up food for digestion. Although chickens with outside access will obtain some grit naturally, they aren’t likely to find all they need in a small yard. Ask your feed store if grit is included in your feed, and if not, add a small bag and a supplement feeder to your order.

Laying hens require calcium in their diets to form eggshells and keep their production cycles strong. Adequate calcium is already added to most laying ration. If your hens have access to a yard they’ll also obtain calcium from eating hard-shelled insects. If you sense that your hens aren’t receiving enough calcium in their diets, you can purchase it separately and provide it, free-choice, in a small feeder. As with granite grit, your chickens will not eat more than they need.

Special Considerations for Laying Hens

Perches

Instinctively, laying hens roost at night. If you don’t provide a perch for them they will do their level best to rest (and mess on) their nesting boxes, food and water containers, feed sacks, ceiling rafters, or anything else they can reach. Furthermore, if perches aren’t supplied, hens will fight for the best spot, feel overcrowded, and put themselves in danger (ascending and descending from ceiling rafters, for instance).

Perches should be made of one- to two-inch wood with slightly rounded edges. Allow twelve inches of roosting space per hen and keep perches a minimum of eighteen inches from the wall. Droppings are at their worst under roosting space. Elongated boot trays or a mechanic’s plastic oil pan makes frequent cleanups a cinch.

Note: Meat birds might play and exercise on perches early in their lives, but you should discontinue access by the time they are five weeks of age because they become large and clumsy. If you decide to allow low perches for meat birds (six inches off the floor only), ensure they have at least two feet of space between wall and perch and eighteen to twenty inches of perch each.

Nesting Boxes

Instinctively a chicken knows to lay eggs in a nesting box. You don’t need to teach her to do so; you simply need to provide an adequate box.

If you don’t provide a nest, the hens will leave their eggs on the floor. Within minutes the eggs become soiled, cracked, pecked at, and potentially eaten by the others. A minor loss today becomes a serious loss in the future. Egg-eating quickly turns into a coop-wide bad habit that cannot be untaught.

There are a variety of nest styles to choose from. Hanging nests, free-standing dark nests, and even sturdy wood crates raised just a few inches off the floor. Your hens won’t be picky but they might have a favorite out of the ones you provide.

You can be creative with nests you make or provide; just be sure they allow for your easy access. A friend once built a partial wall of nests that was accessed by one large hinged door of round holes. She had the coolest coop for miles but collecting eggs in the top row of nests—where you couldn’t easily see what you were collecting—wasn’t fun. Sometimes what she’d pull out was just a round ball of poop. Ugh.

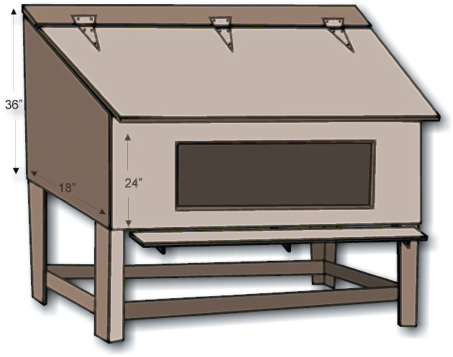

The dark nest is a lumber-saving, age-old design that makes egg collection and cleaning easy.

Over the years I’ve discovered a passion for the dark nest. Built of plywood and constructed in just a few hours, the dark nest can be used by multiple hens without squabbling or rivalry. Each hen requires only twelve inches of nest within so you’ll save on space and material if you need to build nesting boxes anyway. Include a perch on the front and your hens won’t be apprehensive upon entering the dark nest.

Dimensions are not specific as the dark nest can be custom fit to your coop space. The slanted and hinged roof prevents hens from roosting above and allows easy access for egg collection. Rest the finished box on concrete blocks or build it with posts so it is two or more feet off the floor. Adjust the elevation to save your back, as you’ll be stooping over every morning to collect eggs.

If you plan on building individual nesting boxes, here are some general guidelines:

• A size of fourteen inches square works for all sizes of laying hens.

• A lip on the front keeps eggs and nesting material safely inside.

• A height of two feet from the floor might be easiest for the hens, but not so easy on your back. Most hens will use nesting boxes three to four feet off the ground as long as they have the means and the space to ascend and descend without stress.

• A perch in front alleviates stress for hens wanting in and hens already settled inside.

• Three to four inches of litter or nesting material, changed regularly, keeps the area clean and odor free.

Lighting

Laying hens require thirteen to fourteen hours of light per day for optimum health and production. In North America this is only a problem during the shortest winter days.

Although you may be tempted to move your hens to a covered and sunny porch during winter, allow me to remind you of the dust they can create in just a few days. You’ll love your hens more if you leave them where they are, insulate and heat your coop, and add artificial light for the winter months. I’ve found the best results using one standard incandescent bulb and one full-spectrum grow light from the gardening section.

Your chickens will be happiest and healthiest when given outdoor room to roam. They will roll in soil, forage for bugs, pull up roots, ingest sprouts, and enjoy the natural benefits of the sun. If you can provide them a safe place to enjoy acting like chickens and are thrilled to do so, you will be equally distressed to find that within a month’s time their yard is a packed-dirt and barren wasteland.

Some say there is no way around it, that chickens will annihilate any yard you give them in short order. I say there is an alternative.

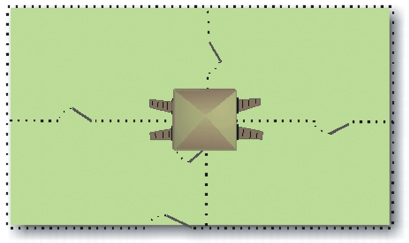

If you build a coop in the center of a divided chicken yard or build a large yard around your coop, you can rotate access to four quadrants while keeping each area viable. This is similar to the rotational-grazing method that manages larger livestock pastures. Concerning chickens, however, rotational grazing is much easier to implement. Four chicken doors within the coop allow you to dictate on a day-by-day basis which quadrant of the yard they will access.

Quad yard for chickens. More gates to build than a standard yard, but so much nicer for chickens that can’t wander about freely.

The most trouble-free birds are those who have at least four times the fenced space out of doors that they have indoors.

My first 10- by 12-foot coop (120 square feet), which comfortably housed two dozen large laying hens, had a 3,000-square-foot yard sectioned into quarters (each quarter being 25 by 30 feet or 750 square feet). Considered overkill by old-school farming standards, this arrangement kept the hens happy and I felt satisfied in the way I provided for them.

Fencing

Chickens are absolutely incapable of defending themselves and every potential predator knows it. Foxes, hawks, wolves, weasels, and raccoons will jump at any opportunity to take one or more of your flock. The list of potential predators doesn’t stop at wildlife. Mild-mannered family pets have also been known to annihilate an entire flock of chickens in less than an hour.

You may be one of the fortunate few who can free-range hens without a loss for years. It was once possible on my farm, too, but in the last five years a large population of coyotes and foxes has moved in. Although I dislike fencing the chickens in, I appease the desire to let them roam free just a few times each year now.

A standard chicken yard fence is four feet high with posts spaced six to eight feet apart. Posts are buried two feet into the soil and, along with corner supports, are located within the perimeter of the fence. Wily and nimble predators can and will climb fence supports if they’re left on the outsides of the corners.

Chicken wire is inexpensive and easy to handle, but the strongest fence is built of a medium-gauge yard and garden wire. With one-inch square holes in the bottom quarter and larger holes on top, this fencing material can keep chicks as young as a month old on the inside and most predators out.

If weasels and raccoons are a nuisance in your area, consider attaching sturdy wire to the underside of the coop.

Perhaps the best defense against predators is to be mindful of the signs they leave from one night to the next. Should you notice a gnawed board, wire that has been pulled away from the post, or roofing material pulled off the coop, take immediate action. Many predators have been known to return night after night until they gain access. Never put off an issue of safety until tomorrow. Tomorrow may never come for your chickens.

Your family dog is also a great defense, but only as a deterrent. While some farmers might tie their dogs near the coop to sound an alarm, this strategy can have dire consequences for the dog should a pack of wolves or a lone cougar wander through.

In broad daylight with the farmer nearby, this bold fox takes a chicken’s life and then stands in open terrain enjoying his lunch.

If you have persistent problems with a particular animal, discuss the situation with other locals who keep chickens. Local wildlife authorities might also have solutions or insight into the problem.

An Afternoon Out for the Girls

Should you decide to let your hens out a few times a year to wander in your gardens and enjoy a little extra space, you’ll want to keep close watch. I only open the gate when I know I’ll be spending the next few hours outside, and I ensure each one follows me into the yard, never leaving my line of sight. After the incident with a very bold coyote just three feet away, I also take my rifle.

I have yet to lose a hen doing so, but only because:

• We have cleared acreage. If a predator is stalking he’d be hard-pressed to sneak up on us.

• A hen will seldom roam from the safety of the flock or within a safe running distance of her coop. Should any of them leave the flock they most often end up at my feet.

• I spend a lot of time with my layers. If I need to get them back into their coop early I just call them in. (There’s nothing magical to this—I simply conditioned them to the call of scratch grain—you can do it too!)

Chicks can be purchased at country auctions, from a local farmer, by mail order, or direct from a reputable hatchery.

My best birds have consistently arrived from a hatchery. Although I’ve purchased some hens and a few roosters at auction and privately, too much is at stake to risk a chance on parasitic infestation and disease. An entire coop can get sick overnight and all will be lost for the sake of one small purchase.

In twelve years I have heard a hundred or more similar tales of woe from my readers on GoodByeCityLife.com. Here are just a few ways that purchasing chicks can go wrong.

You Can’t Always Trust a Seller. One couple purchased three day-old pullets at a farmer’s market. After raising and caring for the chicks for nearly four months, two of their pullets grew to be cockerels, but they seemed to be getting along with each other. Returning home from work one afternoon they discovered the smaller rooster lying nearly dead on the driveway and the larger one delivering some fierce final blows.

Mail-Order Chicks Arrive Dead. A young woman, living remotely and on a quest for self-sustained living, ordered thirty chicks by mail order. Arriving at the courier pickup location on time and excited, she found that the box was full of dead chicks.

Accounts from other readers have cited boxes of chicks that are travel-weary and stressed to the point of sickness.

Receiving chicks by mail order has lost the reliable reputation it once held. The best hatcheries will guarantee live delivery, but that merely equates to a credit of replacement chicks if yours arrive dead. Day-old chicks are shipped by plane (in the cargo bay), by regular postal trucks, or through courier services. Although a newly hatched chick is capable of surviving without food or water for twenty-four hours, it is not capable of thriving in impossible temperatures or managing the stress of being consistently jostled about. A delivery service is not concerned about stress, temperature, or whether live cargo arrives alive or not—they receive the same payment either way.

One New Hen Sickens an Entire Flock. I’ve done this myself. At a livestock auction I met a knowledgeable and friendly seller with a hen I just had to have. I inspected her for lice, leg mites, and overall health, and she seemed perfectly sound. During quarantine the hen became listless and weak and eventually died. Had I released her into the general population I might have lost my entire flock.

The lesson here is no matter how experienced any of us think we might be about raising chickens, or how trustworthy we believe a seller to be, we can always be taken by surprise. Make your purchase from a recommended and local hatchery, no matter how small your order, and arrange to pick up your order personally and directly.

Your feed store might offer a service of pre-ordering and accepting delivery for annual chick orders. The hatchery delivers organized boxes to the feed store and the chicks inside are quickly inspected before you pick them up. This minimizes delivery stress, improper handling, and time in transit.

Ordering and Caring for Chickens

Chickens from commercial growers are sold as day-olds, started (two to four weeks old), and ready to lay. You can further specify whether you’d like cockerels, pullets, or straight-run chicks.

Straight-run orders are filled as the chicks hatch and are therefore cheaper. When raising meat birds, a straight-run order will give you wider variety in finished size. When ordering dual-purpose breeds as straight-run chicks, you’ll have the best of both worlds—roosters to cull for the freezer and hens to keep for laying.

Day-Old Chicks

Day-old chicks cost about two-thirds less than started birds. They are often pulled dry from the incubator, vaccinated for Marek’s disease, and popped into the box for delivery.

Once home, you will need a heat lamp to keep the chicks warm for a few weeks. One 250-watt infrared lamp will keep fifty to a hundred chicks warm, but keep two in case one should fail. A hanging heat lamp placed eighteen to twenty-four inches from the floor allows you to make adjustments from day to night and as chicks grow.

There are two ways to ensure the temperature is perfect for young chicks. The first is to take a temperature reading of 90 to 92 degrees Fahrenheit, two inches off the floor. The second is by observing the chicks’ behavior. Chicks that are too cold will pile on top of each other under the lamp and chirp. If they are too warm they’ll wander away from the lamp or lie down with wings spread and panting if they can’t get far enough away. A sign of correct heating is when chicks are freely wandering within the perimeter of the lamp and occasionally returning to bask in some extra warmth. Feed and water dishes should rest just outside of the lamp’s radius.

Meat birds from the hatchery, directly to you. Freshly hatched chicks are vaccinated, then packed into a box and shipped to the consumer. The chickens in the back of this box are huddling for warmth but are not stressed at the end of their journey.

If chicks will be kept in an area where pets might enter, or that might be drafty, start your chicks in a solid-wall brooding box that is vented above. Brooding boxes can be as simple as a sturdy cardboard box or as elaborate as a fine mesh kennel protected on all sides. If chicks are going directly into a new coop where no other animal can get at them, you can skip the brooder—they are not likely to leave the immediate vicinity of the heat source or the safety of their brood mates.

Keep your chicks’ area clean and dry with a constant supply of fresh water and feed. A base of newspaper with paper toweling on top is absorbent, can be easily changed, and will prevent slippery mishaps. Wood shavings or sawdust are not recommended as litter for young chicks. Chicks will ingest the shavings and end up with swollen, impacted crops that will eventually kill them.

Chicks will have to be taught how and where to drink. Dip a few chicks’ beaks into lukewarm water from a small fount (provide one fount for every fifty chicks) and the others should catch on. Don’t be shy about being overprotective and dipping every beak—I do it!

After the first week and every week thereafter, adjust the height of the fount to the chicks’ chest level to keep kicked litter out of the basin. Make similar adjustments for feeders.

As your chicks grow they will spend less time under the lamp. Make adjustments for their age, the temperature of the room they’re in, or by time of day. If I’m starting chicks in a cool spring I’ll raise the heat lamp every week by an inch (thereby decreasing temperature by 5 degrees) and eventually turn the light off for daylight hours. They are fine as long as they aren’t chirping loudly and huddling. By six weeks they should be acclimatized, but the exact time to remove it altogether is dependent on coop temperature (no lower than 65 degrees Fahrenheit). Close observation of their behavior without the lamp is the best cue.

Started Chicks and Ready-to-Lay Pullets

Started chicks are a nice option for the new farmer. Arriving between two and four weeks of age, vaccinated for Marek’s, and fed a medicated feed to kick-start immunity to coccidiosis, your chickens arrive young enough to bond with, but more established than a day-old.

A four-week-old chick is capable of dealing with low nightly temperatures of 75 degrees Fahrenheit. If seasonal temperatures in your region drop below 75 degrees, add a heat lamp (instructions above in the Day-Old Chicks section) until you’re sure it is no longer required.

Ready-to-lay pullets (sold at sixteen to twenty weeks of age) may have just started laying eggs or will begin within the next few weeks. I like to call them “instant egg layers in a box”—just add coop, feed, and water.

It is common hatchery practice to leave the lights on for twelve hours a day when raising pullets, and to suggest that you increase their day’s light by one extra hour over the course of a week, for the next four weeks—to a maximum of sixteen hours per day. I usually purchase hens in the summer months and let Mother Nature manage the light until winter arrives.

Saving Money on Your Chick Order

Chickens are sold by the hatcheries on a sliding scale. The larger number of birds you purchase, the lower price per bird you’ll pay. If you can double up your order with one or more friends you can save as much as $1 per chick.

If you’re ordering laying hens, you can pay just a few dollars more per hen and get ready-to-lay pullets, which will save you the cost of twenty-five pounds of feed per hen and the need for heat lamps.

If your heart isn’t set on a particular breed, check your hatchery for special deals on overruns and mixed lots. You can often save 50 percent per order through hatchery specials.

Caring for and Feeding Chickens

Commercial feeds are available to suit each changing need of your flock—starting, growing, maintenance, and finishing mixtures—in a choice of three consistencies: mash, crumbles, or pellets. For starting chicks I use crumbles for the first eight weeks, then switch over to pellets for the remainder. Mash has consistently been a dusty waste in my coop.

A few weeks before your hens are expected to begin laying (eighteen weeks for laying breeds, twenty-two weeks for dual-purpose breeds), start changing their feed over to a layer’s pellet a little at a time at first until they are on straight laying ration.

If you’ve purchased straight-run, dual-purpose chicks, this twenty-two-week mark is also a good time to move out the cockerels. Grow them a little longer on grower ration or dress them for the freezer as your time permits.

The meat breeds can be switched over to grower ration by four weeks of age. You will not need to switch their feed again unless you choose to give them a finishing ration in the final weeks.

Another popular feed, but one to stay away from, is scratch grain. Deceptive in appearance, scratch grain looks like it might be the most natural feed for your chickens. Ounce per ounce it is also the cheapest. Scratch grain lacks in required protein and calcium for layers and is not suitable for fast-growing meat breed crosses. Use scratch grain as a treat or training aid only.

Poor-quality feed with nutrient deficiencies creates internal imbalances. Dietary deficiency is the most common culprit for poor egg production or slow-growing meat birds.

How Much Chicken Feed to Buy

Twenty-five two-week-old meat breed chicks eat at least twenty-five pounds of feed per week.

Twenty-five four-week-old meat breed chicks eat at least fifty pounds of feed per week.

Twenty-five eight-week-old meat breed chicks eat well over a hundred pounds of feed per week, now at their prime of converting feed to muscle.

Twenty-five laying chicks (up to twenty weeks of age) will eat approximately twenty-five pounds of feed per week. (Obviously less in the beginning and more towards maturity.)

Twenty-five mature laying hens eat fifty pounds of feed per week.

Save on Feed Costs

Almost 60 percent of the cost of keeping chickens is spent on feed. Although your chickens will show you their own style of wasting feed, other factors are within your control. The following are my top five tips for saving money on feed costs.

• In an effort to save money while raising your own food, the question comes to mind: “Why feed a rooster?”

• At the feed store, when given the choice between mash, pellets, or crumbles for birds over eight weeks old, choose pellets. Less feed will be wasted.

• Know how much feed you’ll need for three weeks at a time and save gas running to the feed store every week. Keep feed bags dry and out of direct sun to protect against rot and staleness, respectively. Rodents such as chipmunks, mice, and rats can chew their way through the bottom of any feed bag or plastic tub and consume or contaminate the entire lot. Keep feed in the bag within a clean galvanized trash bin.

• Feed your chickens as much vegetable scrap from the kitchen and clippings from the garden as possible. The more you feed them from your farm and table, the less commercial feed you’ll pay for. A few exceptions are potato peelings (which are not digestible) and pungent produce such as garlic and onions (which taint the taste of meat and eggs). Most other fruits and vegetables will surely be consumed and enjoyed by your flock. You can help put calcium back into a chicken’s digestion by feeding empty eggshells to them. Just be sure to grind them up well past recognition before delegating them back to the coop.

• Plan on getting meat birds to the freezer before or as soon as possible after their ninth week. Their feed-to-meat conversion ratio begins to decline at this age.

Although stunning to behold and capable of sounding the trouble alarm when predators come around, unless you’re planning on breeding hens you don’t really need a rooster.

Maintain Good Health in Your Flock

Ninety percent of success in raising chickens can be found in these two words: obtain and maintain. When chickens arrive on your land healthy, it doesn’t take much to maintain that state. Clean living conditions, lack of stress, and an adequate supply of clean water are the top three preventative measures against sickness.

Vaccinations are another consideration to ensuring your chickens stay healthy. As some bacterial viruses and diseases are localized, ask a veterinarian in your area if any special vaccinations are required.

Prevent disease, virus, and infection being unknowingly introduced to your coop:

• Rodents and wild birds are notorious for spreading disease as they travel from coop to coop. Manage rodent population with traps or by ensuring they can’t get at feed and grain. Without easy access to food, rodents won’t stick around. Wild birds can be kept out of the chicken yard by adding aviary netting across the top of your yard fence.

• Some chickens are only carriers of a disease and show no signs of illness. Only purchase chickens to add to a flock from a hatchery and quarantine every new chicken for at least a week before introducing it to existing flocks.

• Just as introducing new chickens to a coop can cause the spread of a disease, so might the soles of your shoes carry in sickness if you’ve visited another coop. Before you head off to your own chores, clean and sanitize your shoes after spending time at another coop.

Catching illness before it becomes a deadly outbreak isn’t easy. Your senses have to be fully present for each chicken in the coop, every time you enter the coop. Once familiar with your chickens, you’ll pick up on changes that could be a signal of sickness. Loss of weight or lack of growth in a young bird, consistent drooping heads or hunched appearances, change in comb color or size, dripping noses or eyes, rattling chests, and changes in stool droppings are but a few signs of various illnesses.

Symptoms can be confusing. As an example, loose stools may be attributed to coccidiosis, and decreased laying or weight loss might be a sign of worm infestation, but coupled with other changes these symptoms might signal something worse.

If you notice illness in just one chicken, immediately quarantine it. If all your chickens appear sick, call a veterinarian for further instruction.

It is a fact of life and of raising chickens that not all diseases can be noted and cured in time. In most cases, by the time you notice that a chicken is sick, it is already too late. Even if you could cure the disease and nurse your hen back to health, she might remain a carrier and pass the disease on to others.

Parasitic Infestations

Of the two—internal and external—the most unnerving parasites are external. Unchecked lice and mites quickly turn into a coop infestation. They can arrive on your chickens, can live in your coop from one batch of chickens to the next, and if left untreated, can drag your chickens to death’s door.

Lice and mites spread quickly from one bird to another. You’ll only need to check one or two birds to know if you need to take immediate action. Visit the coop after dark with a friend and a flashlight. Don’t startle sleeping chickens on the roost by waving the light in their faces, just calmly collect one off the roost and shine the flashlight to the base of the feathers by the head, vent, and under the wings.

Lice will leave signs of eggs that look like tiny rice grains. They will also leave scabs on your bird’s skin where they’ve bitten and chewed.

Mites come in two forms—body mites and leg mites.

There will be no mistaking body mites under the flashlight’s beam. They look like tiny red spiders crawling on your chicken’s skin.

Raised scales on a chicken’s legs are a sign of leg mites. Leg mites are discouraged, controlled, and smothered by coating perches and the legs of chickens with daily applications of vegetable oil or petroleum jelly for seven to ten days.

Body mites and lice require a thorough coop cleanout, poultry-safe insecticidal powder, and diligence to the directions on the label.

Coccidiosis

Coccidiosis is an intestinal disease that can weaken and kill untreated chicks. Most adult chickens have an immunity to the organism that causes it, but can still suffer from the disease. You will instantly recognize the spread of this illness by loose droppings throughout the coop. Medication can be readily purchased at any feed supply store.

Starter feed for chicks often contains Amprolium, a medication developed to control intestinal coccidia while allowing chickens time to build up a natural immunity. Ask at the feed store if Amprolium is present in your feed, and then make a personal decision about the value of pre-medicating poultry that is not sick.

Marek’s Disease

Marek’s disease is a cancer-causing viral infection. The disease is spread via feather dander and inhalation. Most hatcheries automatically vaccinate for Marek’s within the first few hours of hatching.

The Joy of Eggs

Crack a farm-fresh egg into your frying pan and you’ll find a firm white with a deep-orange and substantial yolk. These eggs look and cook a little differently than the grocer’s version. Yolks are darker, whites are firmer, and the air sac within is most certainly smaller. Higher density and less air space within the shell makes these eggs economical as well. Fewer farm-fresh eggs are required for large batch baking, and the whites create more volume when whipped.

As for the grocer’s version of an egg, the time to market has some bearing on the lack of quality and taste, as most eggs are already a week old by the time they hit your shopping cart. However, a hen’s diet and living conditions are the two main contributors affecting the taste and density of any egg—farm-fresh or commercial.

Years ago I was surprised to learn that farm-fresh eggs can be as dull as the commercial egg. For years my in-laws raised cooped-up Leghorns that were never allowed to forage on the land, never given garden or table scraps, and never enjoyed the wonders of direct sunlight. Take note: if you don’t take the route of reproducing an egg factory in your own coop, you won’t run the risk of having unspectacular eggs.

Give your layers a yard of sunshine, clean and spacious living conditions, fresh water at all times, and a varied diet. You’ll be well rewarded for your efforts.

Freshness Tests

As eggs sit in storage (whether destined for the grocery store or awaiting use in your own refrigerator), they lose moisture through the shell. This evaporation creates an air bubble noticeable only when you hard boil the egg or hold it to a light source. If you’re uncertain how old an egg is, check the bubble. Fresh eggs have virtually no hollow within the shell.

You can also float an egg to see if it is fresh. Fresh eggs sink in a bowl of water. An egg that stands upright is only a few days old. Older eggs float and aren’t fit for consumption.

Cleaning and Storing Eggs

Freshly collected eggs have an invisible layer of protection upon them called a bloom. The bloom keeps moisture in and surrounding air out. If you scrub off the bloom before storage you compromise the egg’s natural ability to stay fresh. A quick rinse in water slightly warmer than the egg maintains the integrity of bloom during storage.

Keep your eggs in the vegetable tray of your refrigerator—even if space is tight. Specialty shelves on the fridge door are not actually suitable for egg storage. Inconsistent temperatures and frequent jumbling about each time the door is opened will age eggs well before their time. Eggs gathered fresh and stored in a crisper easily stay fresh for a month.

There will be times when you have an abundance of eggs and no time to use them all. You can freeze them (out of the shell) for future baking with just a shake of the salt shaker per half dozen. I beat them in lots of four and six, as those are the quantities most often called for in the recipes I use. Freeze them in small glass bowls with tight-fitting lids or BPA-free freezer bags.

A Closer Look at Farm-Raised Eggs

Let’s clear this up once and for all: The color of an egg’s shell does not determine nutritional quality.

The belief that a brown egg is higher in nutritional value than a white egg is a throwback from past generations. For the last thirty years, most laying hens raised commercially were white egg breeds. On the flip side, most layers raised on the farm were dual-purpose breeds, most of which lay brown eggs. Since we already know that farm-raised eggs are of higher nutritional value, you can see where the confusion began. Imagine the misconceptions that will arise once the Araucana and Ameraucana’s eggs gain in popularity! These eggs have shells in various shades of blue, green, and olive.

Yolk color suffers from similar misconceptions. It is not the freshness of the egg that has the greatest impact on yolk color, but the diet of the hen that laid it. Free-range and partial-range hens’ eggs will have a dark golden to orange yolk. It is the adequate supply of fresh greens in the diet that creates the coveted hue. If your hens don’t get out much or if you find your eggs to be dull in winter months, you can supplement their lay ration with kitchen scraps of broccoli, green beans, and lettuce.

On occasion you might find colored spots within an egg. The spots within unfertilized eggs are completely natural and harmless, although not necessarily desirable. The cause is the tiny blood vessels within the hen during formation of the egg. It will not harm you to eat it or the egg it appeared in, but you might prefer to remove it before cooking. The common misconception is that this is a sign of embryonic development. Most laying hens have never seen a rooster.

DID YOU KNOW?

You need to add two minutes to your cooking time when boiling farm-fresh eggs.

Soft-boiled store-bought eggs = Three minutes

Soft-boiled farm-fresh eggs = Five minutes

Hard-boiled store-bought eggs = Ten minutes

Hard-boiled farm-fresh eggs = Twelve minutes

How to Hard-Boil Fresh Eggs

Try this the next time you need to make a plate of devilled eggs for tomorrow’s community dinner using the eggs you collected just this morning.

After hard-boiling fresh eggs from the barn, run cold tap water over the pot of eggs for one minute. Allow the eggs to rest in cold water for another four minutes. Break each shell by applying slight pressure while rolling the egg on the counter. Peel the eggs under water. The result? A perfectly peeled, fresh hard-boiled egg without the telling lack-of-freshness gap seen in aged eggs.

The day will come when, either individually or as a lot, your chickens are ready for the butcher. You can take on the task yourself—farm wives and children have been doing it for centuries—as long as you don’t intend to sell the chicken to others. Each chicken will take about twenty minutes to prepare for the freezer.

If you’re pressed for time, have more than twenty chickens to butcher, or don’t have the stomach for the task or volunteer assistants, there are other reasonably priced options for the backyard chicken farmer.

Poultry Processing Services

Scattered throughout North America, you’ll find people charging just a few dollars a bird to come to your property and take your chickens from coop to freezer for you. They arrive at your door with a trailer full of equipment and supplies. Asking for nothing more than directions to the barn and the closest hookup for a hose, they set to work and a few hours later return with bags upon bags of perfectly plucked and dressed chickens.

If they don’t mind you helping and you don’t slow them down, spending a few hours with this group is an education in itself. You will quickly learn the most efficient and health-safe methods to move a chicken from coop to plastic bag.

Often run as a cash-only seasonal business, the service may not be as professional as you’d like. The owner may not be government-certified, so you will need to assess your comfort level with having this group handle food that will one day be on your dinner table. You are also unlikely to find these people in the yellow pages. Ask people in your area also raising chickens for referrals and contact numbers.

The alternative to the on-site butcher is a professional facility that specializes in homegrown poultry. You deliver live chickens to the facility, and then return the next day for pickup. Unlike the on-site option, you need to have enough chickens to make it worth two trips to the facility. These specialists are government-inspected and licensed, and are found in the yellow pages. If you can’t locate one, ask for referrals from feed store staff.

If you’ve never butchered poultry, the best preparation is to spend a day with an experienced person. Offer to pay an old-timer or a farm wife in cash, or with a return of time, for a half day of work processing poultry for the freezer. No finer instruction exists than to learn hands-on with experience by your side.

The instructions below are not intended as a complete education in butchering chickens, but merely a guideline of the process.

The Day Before

Feed given twenty-four to thirty hours previous will be found sitting in the chicken’s crop, wasted. Time the chickens’ last meal so that you are neither wasting feed nor adding unnecessary cleaning chores to the task.

Setting Up

This is an outside, messy task. Wear comfortable chore clothes. You’ll need a work table, an axe, a large pot or bin of hot water, sharp knives, poultry shears, a small set of pliers, rubber gloves, garbage bags, easy access to running water, and if possible a screened tent or garden gazebo to work under. Flies and wasps will be exceptionally annoying.

Inside the house you’ll need a sanitized sink or basin full of cold salted water. You’ll also need to have large plastic freezer bags on hand.

If you’re planning on butchering more than four chickens, having some company (even if just a radio playing) keeps monotony at bay.

Order of the Day

The order to be performed is:

• Catch and kill the chicken

• Allow it to bleed out

• Soak to chill

• Bag for the fridge or freezer

If you’ve trained them, catching the first few chickens is easy. After three you’ll have no choice but to corner each, one by one. Chickens sense that today is different than all other days. They are hungry, members of their flock are being carted out, a commotion can be heard outside, and the smell of trouble is in the air.

An Honorable Death

Knowing that you’ve intentionally raised to eventually kill can be unsettling the first time. It becomes less unnerving every year but it is never without emotion. Having a weak spot for animals by nature, I’ve somehow grown to adopt the farmer’s creed: “If you raise it to eat it, you had better be man enough to kill it.”

In the end I count it honorable to perform this task myself whenever possible rather than have a stranger attend to it. I literally thank each chicken I carry to the chopping block.

Whoever should perform the task, it should be carried out calmly and swiftly. Stress and suffering does nothing for the taste and texture of meat, nor does it honor the life that feeds you.

There must be fifty ways to kill a chicken. The workers at the slaughterhouse hang them by their feet on a moving rack, dip their heads into an electrified bath, and then slit their throats as they pass by. The traveling poultry trailer places chickens upside down in a killing cone, stretches their necks out, cuts their throats, and lets them bleed out from the cone. Small growers also use cones and pierce the chicken’s brain through the back of the mouth with a sharp pick or knife.

Killing cones are popular tools of choice. They are inexpensive at the feed supply store, or you can make your own. A round plastic two- or three-gallon jug with the spout and the base cut off works fine. Chickens can hang in the cone until they have fully bled out, containing the mess to one area.

It has been said that if you hold a chicken upside down for a minute it will go to sleep. This has never worked for me because I’m not one to stand the sound of a scared bird. Instead I remove each chicken from the coop and calm it. With one hand on both feet and the chicken’s chest laid on the chopping block, I swing the axe. Immediately lifting and holding my chicken away from my body, I allow it to flap unrestricted for about a minute to bleed out. The belief is that flapping assists in pumping the blood out of the body.

Do be careful either to let wings flap without restriction or not at all. Knocks and bumps will bruise the meat of the bird.

A Quick Scald

Once bled out and with head fully removed, hold the chicken by the feet and dip into 140-degrees-Fahrenheit water repeatedly for forty-five to sixty seconds. Dipping is an art in itself—dip longer if water is not quite hot enough, shorter for water hotter than the recommended temperature. The outcome will be loosened feathers without burned skin underneath. Some chickens take a little longer, some a little less.

As soon as you remove the chicken from the water, lay it on the work table and start plucking. Pull feathers, by the handful, in the direction they were growing. This only takes a few minutes per bird if you’re working alone. Cut off the feet at the joint, then rinse off the chicken and your work surface with cold running water.

A Cleaning Out

Laying the chicken back onto the work surface, remove the tail and the pointed oil gland at the base of the tail. Ensure that all the yellow substance inside the gland is removed. Using poultry shears or a boning knife, remove the neck and pull the crop and windpipe out from the cavity you’ve just created.

Splitting a young chicken up the back with poultry shears makes the remainder of the cleaning out process easy and educational for an inexperienced butcher. It affords the observation of the inner workings of a chicken before you ever decide to reach blindly inside to remove entrails.

Whether splitting or processing as a whole bird, take care not to pierce the green bile sac of the liver. It will taint and ruin any meat it touches.

To butcher a chicken whole, make a shallow, somewhat keyhole-shaped incision from the base of the rib cage nearly to the vent and then around the vent. You can reach gently inside, moving your gloved fingers to the spine, and literally scoop out entrails in one move. If your chicken is large and your hands small you may need to reach in again to fetch heart and lungs at the front of the chicken’s body. You’re nearly done!

If you keep and use organs, remove the green bile sack from the liver (be certain not to cut into it) and tubes from the heart. Similarly, split the gizzard in half to remove the tough yellow lining. Wash and place neck, liver, heart, and gizzard into cold salted water while you finish the chicken.

If you’ve split and then cleaned out a chicken, you can freeze half birds for the barbeque or cut each half into individual pieces for the deep fryer. To butcher into pieces, use a boning knife at each joint for wings, thighs, and legs. Separating back from breast meat will require a closer cut with a carving knife.

Rinse the chicken inside and out, then immerse in slightly salted chilled water. When the temperature of the chicken has reached current air temperature or cooler, drip and pat dry, bag, and refrigerate for two days to age and tenderize. If you don’t have room in your refrigerator you can place the bags directly into the freezer with similar results. Rotate your poultry two or three times a day for an even freeze.

Supplementary: Raising Turkeys

If you’ve ever eaten a homegrown turkey you’ll never question a desire to feed one. So unlike the dry, almost sinewy, Christmas turkeys of the past, you’ll swear it is an entirely different bird.

Personally—having eaten roast turkey dinner in more than thirty cooks’ kitchens in forty years—I had never really enjoyed the meal. Until the day a farming friend served me the most delicious poultry I’ve ever tasted—a home-raised turkey.

A farm-raised turkey grows nearly as fast as a meat chicken and has similar feed-to-muscle conversion. They require no extra time (except in the first week) in chores and are easier to butcher, as feathers are fewer and the body cavity is larger. You can grow them to a family-appropriate size without worry of overgrowth and sparring among the male birds.

Growing white production breeds is the most common, as the finished bird has clean and bright skin with tender, short-fibered muscle. Large white hens are capable of reaching a fourteen- to sixteen-pound live weight in just four months. Toms will easily reach twenty-five to thirty pounds in five months. Dressed turkeys finish between 70 and 75 percent of their live weight.

Whether raising hens, toms, or a mix of both for three months, four square feet per bird is recommended. If growing on to five months, allow six or more. As always, my space recommendations are slightly higher than industry standards. Increasing these numbers to 30 percent more floor space plus a fenced, protected, outdoor yard adds quality of life and creates tastier meat.

This is not your average Christmas dinner! Home-raised turkey is considered an altogether different breed of poultry—unmatched in taste and tenderness.