Speculation about who would fill the top jobs in the penal system had become feverish. “It’s gonna be a whole new ball game when Maggio takes over, Rideau,” one security officer said to taunt me.

One afternoon in mid-March, I was sitting behind my desk in the Angolite office with my feet up when the door opened. A well-built, good-looking blond man wearing a tan leather blazer stepped into the room. His movements exuded confidence, strength, and power, like the gunfighters in the cowboy movies of my childhood. “I’m looking for Rideau,” he said, walking over to the large chair and sitting down. “I’m Ross Maggio.”

I didn’t move. “Glad to make your acquaintance,” I said. “From the way security talks, you’re the new warden, even though the governor hasn’t made a decision yet.”

“I heard a lot about you and wanted to come by and see you. You’re the one who wrote that article on the rodeo a couple years ago, eh?”

“I did. And did you give the behind-the-scenes order to have me locked up for writing it?”

Maggio smiled. “Didn’t have anything to do with it,” he said. “What makes you think I had something to do with it?”

I shook my head. “Just asked.”

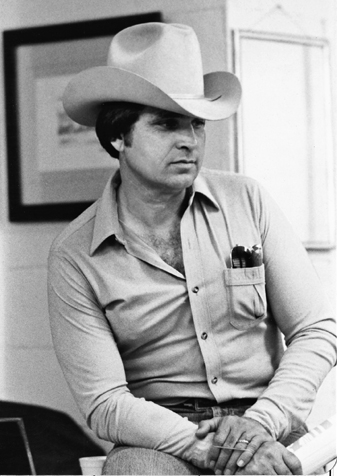

Ross Maggio, Jr., began talking about himself, his years with the corrections department, his philosophy. He was thirty-six, with a degree in agriculture. He looked and talked like he could have been a rancher, a businessman, or a hit man. There was a hint of violence about him.

The next time I saw him was on March 20, 1976, the day after the governor appointed Phelps to head the corrections system. Griffin Rivers, thirty-six, the only Louisianian in the corrections system to hold a master’s degree in criminal justice, was to serve as his deputy, the first black ever to occupy that position. Maggio was named warden of Angola, the youngest ever.

I went out that morning to cover the transfer of seven hundred Angola prisoners to Dixon Correctional Institute, a new facility opened to relieve overcrowding, and found Maggio supervising the operation. Beaubouef, no friend of mine, was at his side, implying a relationship between the men that gave me pause.

That afternoon, a cheerful Phelps and Rivers visited the Angolite office. I had met Rivers some years before when, as a criminal justice instructor at Southern University, he brought his class on a tour of the prison. He was hip and sophisticated. He greeted me like a long-lost friend. “You know, walking through this place is sort of like walking through the old neighborhood where I grew up in New Orleans,” he said. “Man, I recognize a lot of old faces I came up with, men who disappeared somewhere along the way. Now I see where they disappeared to.”

When Rivers left, I said to Phelps, “I’m glad for your appointment, but your new warden bothers me.”

“He shouldn’t,” he said, looking into my eyes. “I’m his boss, and he’ll do what I tell him to do.”

“Your office is in Baton Rouge,” I said, implying it was far removed from what was happening at Angola.

“It may have been that way in the past, but it’s going to be different as long as I’m director,” Phelps said. “You’re going to see me around this prison almost as much as you did when I was warden. And I’m going to be dropping in on you to see how The Angolite is coming along and to visit and talk with you, just like I’ve been doing since we first met. There are a lot of things wrong with this place, and it’s going to take some drastic changes to put it in order. You’ve got a role to play because I want us to do with The Angolite what we said we’d do with it—I want it to be a meaningful source of information for the inmates and not some boarding-school newsletter. Nothing is changed in that respect. You are the editor. Peggi is your supervisor. Anytime you disagree with her on something, you can appeal her decision to Warden Maggio. And if you’re not satisfied with his decision, then you appeal it to me. I’m the publisher.

“Don’t get pessimistic on me before you give it a chance to work. And the same applies to Ross—don’t prejudge him. He might surprise you. I’ve known him for a long time. We started working in corrections across the desk from each other on the same day. And Ross is who Angola needs as warden right now. This prison has been a headache for the state for longer than anyone can remember. If I do nothing else during my tenure as director, I’m determined to clean it up. We’re going to regain control of this penitentiary, end the violence and bloodshed, and make it safe.”

As Phelps warmed to his subject, he grew indignant. “The inmates are going to holler that we’re fucking them over, but they don’t have to strong-arm, rape, and kill each other. I’m not going to let that happen. Ross is the right personality for this situation. The inmates will find that he’s willing to deal with them on any terms they choose. They want to cooperate—fine. They want to fight—Ross will oblige them. He has a job to do and how he does it is going to be primarily determined by the inmates themselves. But make no mistake—the job is going to be done.”

While Phelps in his new job coped with the lawsuits, political pressures, and the howls of a public made even more hostile by the massive relocation of prisoners throughout the state, Maggio cracked down at Angola. Personnel were hit first; scores of entrenched employees were fired, demoted, transferred, or forced into retirement. “You can’t expect to rehabilitate the prisoners until you rehabilitate the staff,” Phelps explained. Among the first to go were Lloyd Hoyle and William Kerr, the two officials who had ordered me locked up in the Dungeon over the rodeo article.

When a prisoner escaped from the cellblock, Maggio unprecedentedly suspended the top cellblock supervisor. “Whenever something goes wrong, they point the finger at the bottom-line correctional officer and fire him,” he said. “The way I see it, the man on the bottom will only do his job to the extent his supervisor makes him do it. When something goes wrong, it’s the supervisor’s ass I want, and I don’t care if he was a thousand miles away from the incident when it happened. Hold the supervisor responsible for what his men do, and he’s gonna make it his business to see to it that they do their job right.”

Maggio also introduced surprise roadblocks along Angola’s blacktops to search employees’ vehicles, seeking to halt the flow of narcotics, weapons, and other contraband into the prison.

In his first meeting with inmate leaders, Maggio brushed aside questions about his plans for rehabilitating them. “Rehabilitation has a hollow sound to it when you’ve got people being killed as they’ve been killed here,” he told us. “Before you can think about rehabilitation, you’ve got to have a degree of order and discipline. No prisoner should have to wonder whether he’s going to walk out of this place alive.”

Unlike typical corrections officials who resort to wholesale lockdowns—where prisoners are confined to their cells or dorms, and all inmate movement is halted throughout the prison—to combat violence, Maggio shunned actions that punished rule-abiding inmates. He ordered the immediate but selective lockup of all known and suspected gang leaders and members, drug dealers, homosexuals who created problems, and suspected strong-armers who raped weaker inmates or forced them to pay protection. When lifer Terry Lee Amphy was stabbed to death in his dormitory—the first prisoner to be killed in 1976—Maggio swiftly ordered every inmate found with anything resembling a weapon to be locked up. Sophisticated electronic devices and walk-through metal detectors were installed. Searching—“shaking down”—prisoners at every gate inside the prison was now required, and there were surprise shakedowns as well. A special detail of officers was assigned the task. Officers could no longer warn inmates with whom they had alliances, something that had become a common practice. So many men were locked up that each of the prison’s two-man disciplinary cells overflowed with as many as eight men.

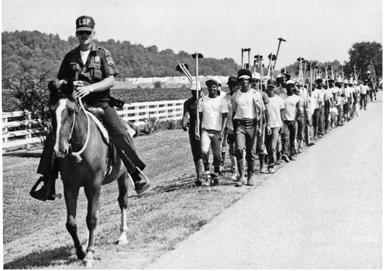

Those prisoners without jobs or who had been ducking work were now sent to the fields. Prisoners complained that picking cotton would not train them for jobs in society. Maggio agreed, but told me, “We’ve got to have something to occupy their time, burn off some of their energy. Otherwise, they’ll just sit around, figuring ways to beat us or each other.”

With the grip of the former inmate power structure and cliques broken by the massive transfer of prisoners out of Angola as well as the lockups, new and strict security regulations went into effect. The freedom of movement formerly enjoyed by inmates came to an abrupt end; passes were required to go through gates and to travel from one area to another. The security force grew from 450 officers to 1,200. An officer was stationed in every area of work and play, even locked inside the dormitories at night with the prisoners, armed with only a beeper that, when sounded, brought fellow officers stationed elsewhere in the prison rushing to his aid.

Prison employees replaced prisoners who had previously served as clerks in many key prison operations, positions that enabled those prisoners to profit by exploiting other inmates. Inmates complained to Phelps about the shakedowns and charged that the stringent measures imposed by Maggio were unnecessary. “None of this had to happen,” Phelps replied, “but you’ve made it happen. You don’t have to do the things that you do to each other.”

Maggio continued Phelps’s practice of not operating the prison from the warden’s office. He ordered all top officials to create a “floating administration,” moving about the prison and accessible to the inmate population. Maggio popped up everywhere, at any time, dressed in anything from a business suit to the blue denims worn by the prisoners. That kept his employees doing their jobs, which in turn kept them riding herd on the inmates—exactly what he wanted.

Maggio was a man given to action, tolerating no nonsense and accepting no excuses. One day he fired a yard supervisor on the spot. When the officer disputed the dismissal, Maggio ripped the badge from the officer’s shirt and punched him in the face, knocking him to the ground in front of inmates and other employees. Except for rare instances like that, few prisoners knew that he was cracking down as hard on his employees as he was on them.

One night he busted down doors in eliminating an illicit whorehouse on B-Line, which he had ordered closed when he took office. A week later, during a ceremony attended by employees and inmate organization heads, I asked him about the incident. He grinned, relishing it.

“Chief, you shouldn’t underestimate those B-Liners,” I said. “Some of them are not much different from inmate gangsters down the Walk. They play for keeps, and they’ve put skates under wardens before you.”

Maggio’s ego was pricked. “They may have run other wardens, but they’re not going to run this one,” he said, turning dead serious. “They may kill me, but I won’t run. I don’t back down.”

In the beginning, he and Beaubouef roamed about the prison armed, supervising and policing everything. Maggio personally led the manhunts for escapees in the rugged wooded terrain around the prison, a pistol strapped to his leg. He got lost once and radioed in. Told to stay where he was, that a search party would go out and meet him, he replied angrily: “You just tell me my goddamn location, then tell me which way those prisoners went!” Maggio was in his element; he was a man who enjoyed the macho games and was determined to succeed at them. His behavior won him respect in Angola, to the point that inmates dubbed him “a gangster,” the ultimate compliment. He loved hearing that.

As Maggio settled in, my profile grew and my writing career blossomed. Penthouse published my feature about the plight of incarcerated veterans in its April 1976 issue. Louisiana’s second-largest paper, the New Orleans States-Item, did a front-page series on Angola on April 14. One article, “Rideau: Piercing the Walls with Words,” was a lengthy profile by reporter Jim Amoss about my self-education and rehabilitation during the fifteen years of my imprisonment; another article, “Jungle,” was by me. The timing was fortunate, I thought, because in a month the state pardon board would be hearing my plea for freedom.

But two weeks after the States-Item articles appeared, I received my first and only disciplinary report when a guard searched my locker and found “contraband”—a bottle of Wite-Out I had taken to my dorm so I could continue working after hours on The Angolite. It was the only disciplinary report ever issued in Angola’s history for Wite-Out, a product universally used by inmate clerks. In an environment where strong-arming, dope peddling, prostitution, and fights were the stuff of disciplinary hearings, the disciplinary court declared me guilty but gave me only a verbal reprimand. Achieving prominence while in prison, I learned, exacts a price.

Even that reprimand anguished me, because I had hoped to present a blemish-free conduct record in support of my petition for clemency. “We’re interested in what’s happened to a man since he landed in the penitentiary, rather than in the circumstances of the offense,” pardon board chairman John D. Hunter had explained to Amoss. “If a man has a good prison record and shows a willingness to rehabilitate himself and gives us an indication he can operate in free society, we often give him a cut to a certain number of years, if the situation warrants it.” As I said, I expected a favorable response from the board.

I was not permitted to appear before the pardon board to plead my own case, so others were to appear on my behalf: my mother; Sister Benedict Shannon, who was still my spiritual advisor; Lake Charles NAACP president Florce Floyd; and Louis Smith, the director of the Baton Rouge Community Advancement Center, who sponsored Vets Incarcerated, our self-help program at Angola for military veterans.

I knew I was in trouble from the moment I awoke on May 19, the day the board convened in Baton Rouge to hear my petition. The inmate who slept in the bunk next to me told me he had heard on the radio that “Frank Salter is personally appearing with your victim to oppose your release. They talked about you pretty bad, man.”

It was the first time in Salter’s sixteen years as a district attorney that he made the 125-mile trip from Lake Charles to Baton Rouge to oppose clemency for anyone, including a string of murderers whose sentences were commuted during that time.

He would be there because of a scandal he was involved in. A failed extortion attempt by Lake Charles AFL-CIO union boss Donald Lovett to force Arizona industrialist Robert Kerley to hire a company partly owned by Salter to construct an ammonia plant had culminated in mob violence on January 15 and the murder of construction worker Joe Hooper. Lovett was indicted for manslaughter, and his trial was set for May 10, nine days before my pardon board hearing. Salter had by then become the subject of increasing criticism as his long, corrupt relationship with Lovett was exposed by the media. His appearance at my hearing was a public relations ploy on his part to win back some public favor.

I went to my office and sat quietly behind my desk. An hour or so later, a classification officer came to the door. “Long distance,” he told me in a hushed, conspiratorial tone as we moved toward his office, where I closed the door behind me to take the unapproved call. It was Louis Smith.

“Man, it’s all bad news,” he said. “We had everything down pat and the board had told us it was a sure thing, especially since Warden Henderson was requesting that you be released to him in Tennessee. We were all waiting for the hearing to begin when Salter showed up. Florce Floyd looked like he had seen a ghost. He walked up to Salter and said, ‘Frank, you promised me that you wouldn’t come.’ The bastard just smiled and said, ‘I changed my mind.’ He came with Baton Rouge district attorney Ossie Brown, and they brought their own reporters. They set up TV cameras in the pardon board room, and you could just see the reaction on the board members’ faces. They were intimidated.”

I thanked Smith for his efforts and returned to my office.

Salter’s appearance gave him the desperately needed dose of law-and-order publicity he was looking for. He exaggerated and even fabricated various aspects of my crime. I couldn’t challenge him, because the board’s policies forbade granting clemency to a prisoner who disputed the facts of his case; that was seen as a refusal to accept responsibility for his crime. In my office, I suddenly felt old and very, very tired.

I don’t know how long I sat staring at the framed painting on my wall that an inmate artist, Oscar Higueras, had given me. A single warrior stood on a small hill, a bloody sword in his hand, surrounded by hordes of enemy warriors, some lying dead at his feet. His situation was hopeless, but his face and posture bespoke a determination to die fighting. I related to it. I pulled a cassette tape out of my desk drawer. I listened to Sam Cooke singing “A Change Is Gonna Come,” then the gutbucket blues of Guitar Slim, wailing, “The things that I used to do/Lord, I won’t do no more.” It was the way I dealt with hurt, loss, depression. After sinking as far as I could emotionally, I would emerge strengthened, with an angry determination to prevail over my situation.

There was absolutely nothing I could do about the politics and politicians that sandbagged me. So I plotted escape. I planned to set up a speaking engagement for that purpose. Dot would pick me up and drive me to a house where I would remain hidden for several weeks, until the manhunt and publicity died down. I planned to go to Brazil, which had no extradition treaty with the United States. If I was successful, she would join me there, and we’d start our lives anew. I began to study Spanish, not realizing that they speak Portuguese in Brazil.

When it came time to put my plan into action, I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t betray C. Paul Phelps. He had been a mentor and a friend. Phelps had told me, “If I overrule my officials and I approve you to travel out of this prison”—which he had—“and you escape, my career in corrections is finished.” I had given him my word.

“I believe they’re wrong about you,” Phelps had said. His words haunted me. He was the only official to express a belief in my basic goodness, and the first person in my life ever to really trust me, without reservation, not only to do the right thing but to be a certain way. At the last minute, I scuttled my escape plan. I was a prisoner no longer held by force but by the person I had become.

I set about trying to improve The Angolite. I wanted to make it a better magazine than the whites had made it, for my ego and because, with the civil rights movement providing me a frame of reference, I felt that becoming the nation’s first black prison editor had given me a chance to do something good, to redeem myself, and to make my people proud of me. And, as the first editor of an uncensored prison publication, I had to prove that the censorship that prevailed in the nation’s prisons was unnecessary and wrong.

I had an eighth-grade education and a crew of untrained high school dropouts for a staff. I knew something about journalism from writing “The Jungle,” and a little less about publishing from my experience with The Lifer, but I had an instinct for what I felt would be right. The Angolite was the only publication serving the Angola prison community of some five thousand people, including prisoners and employees. It commanded no respect from either side. Under my editorship, club, religious, and sports activities were relegated to the back pages. I had shifted the magazine’s focus to studying and reporting on the Angola prison community and the corrections system in the same manner as any local newspaper covered its city, with real news and features about the world we lived in and the things that affected us. I wanted the magazine to deal with the realities of prison life. I wanted to humanize stories, to give the reader the flavor of prison and its frustrations, its people, its misery and madness, and to give keepers and kept a sense of each other.

I ordered a camera so I could expand the use of pictures, showing the prison world and its people. Security objected to Maggio on the grounds that we might take photos of an officer doing something embarrassing. I argued to Maggio that officers are not supposed to be doing anything embarrassing. He approved the purchase of the camera as well as a telephoto lens. Members of the Angolite staff had permission to carry a camera and a tape recorder anywhere we wanted inside the prison. It was the first time in the history of Angola that inmates had such privileges, and probably the first time it happened in any prison in America. It triggered paranoia on the part of much of the personnel. To minimize problems, Peggi Gresham often paved the way for us with the top official of whatever area of the prison we planned to visit with our camera and recorder.

My predecessor had encouraged inmates and organizations to write articles about themselves and their activities, which made his job easier. I eliminated the practice and informed everyone that all articles would be staff-written to ensure accuracy and objectivity. I vowed that The Angolite would never again be controlled by those wanting to promote their own interests; even staffers had to agree not to write about themselves or their cases. Still, I was confronted by those who wanted me to make exceptions to the new rules, including the chaplains, who demanded that a page be set aside exclusively for use by their office.

“Every inmate publication that I know of in this country does it,” Protestant chaplain Joseph Wilson argued. “I think you have a responsibility as editor, Wilbert, to do it for the spiritual good of the inmate population.”

I had known Wilson since my days on death row. He was typical of Protestant chaplains at Angola—a religious bigot and spineless bureaucrat who, unable to compete for a congregation in free society, took a guaranteed state paycheck, health care, and a pension instead. It was a waste of tax dollars. More prisoners attended religious services conducted by inmate preachers than by Wilson. The Catholic chaplain was no better.

“We have a conflict of interest,” I said. “Your responsibility is to save souls; mine is to produce an unbiased newsmagazine. And I can’t think of any area of human thought where impartiality is more impossible than in religion. Every religionist has a different belief of what the truth is.”

Wilson was indignant—especially when Phelps backed me up.

Later, when the warden’s office sent me a directive to the inmate population from Phelps, I wanted to see just how far my independence went. I refused to publish it.

“Rideau, he’s the director,” Gresham said to me.

“I know, and he’s the same man who told me that I don’t have to publish anything I don’t want to. The warden’s office has more immediate and effective ways to get that message to the inmates.”

Phelps clarified things by saying that he had merely asked the warden’s office to pass his directive on to The Angolite for our information. Whether it was worthy of publication was left to the discretion of the editor. Phelps’s personal support gave me freedom to do whatever I thought necessary to improve the publication. It was an entirely different story with the inmates.

Most of the problems during the early stage of my editorship came from blacks who, having been denied a voice in the past, harbored high expectations with me in control. Since getting off death row, I had been their writer—the prison’s first black writer—as editor of The Lifer, as a newspaper columnist, and as a freelance writer. They had given me their unflinching support. Now they applied immense pressure for me to make The Angolite a black publication, just as it had been a white publication throughout its quarter-century history. This was my power base, the prison’s overwhelming majority, whose support I would need in future battles to make The Angolite the publication I wanted it to become. To relieve the pressure, I made one concession: When Bill Brown paroled, I did not replace him, leaving the editorial staff—me and Tommy—all black until it became politically possible for me to add a white.

Blacks also expected favored treatment. While coverage of them, which had been minimal, would naturally be increased, I was determined that race would not influence anything in the magazine. Many blacks were urged by their leaders to shun me. Some did; most didn’t.

When I refused the demand for a column by Narcotics Anonymous, the prison’s black “outlaw” organization, they began their own campaign to pressure me. Confronted in the education building one night by their leaders, I told them The Angolite didn’t belong to prisoners, that it was published to provide news and information for them. Besides which, I said, “The Angolite has been here for years, and the white boys had it all that time. But you never got these dudes together to try to pressure them like you’re trying to pressure me.” I paused; then in a whisper, I said, “Now, you were either scared of those white boys or—”

“I ain’t scared of no fucking honkies, niggah!” was the response.

“Yeah, you were scared of ’em!” said Lionel Bowers, a “family” member who had accompanied me to the meeting. His voice boomed from behind me. He was a big man, and now he tapped his chest angrily. “That’s right—I said that! Long as the white boys had that paper, you ain’t messed with them. But the first time a brother get it, you can’t wait to fuck with him. That’s what’s wrong now—y’all crying about white folks, but they don’t have to hold us down, we’ll do it for ’em.” He turned and slammed his fist on the windowsill, furious. “And if anybody got an argument with that, then you better hit me in my face, because I’m through talking.” Between the truth of his words and the obvious fury of a big man who was universally liked and respected, they weren’t going to take up his challenge. The moment had been won, but it was a temporary peace.

The biggest problem, I gradually learned, was that no one wanted truth or objectivity. Personnel wanted only good things said about them (especially by a black editor). Prisoners wanted a one-sided publication lauding inmates and criticizing guards, and conveying to the public how badly they were being treated, a desire that increased in direct proportion to Maggio’s increasing control of the prison and their behavior in it. Criticizing anyone in The Angolite, therefore, was potentially dangerous—the employees controlled my world, and I had to sleep among the prisoners. I would gradually have to condition everyone to the idea of being criticized in print.

I was undergoing an educational process that would influence the way I saw and thought about things. Phelps was taking me to meetings where I observed deliberations prisoners never had access to—on how to turn inmate labor to enterprises profitable for the Department of Corrections, on the problems field supervisors had in meeting their harvest quotas when the medical department issued light-duty status that kept too many injured or ill inmates out of the fields, on the processes by which the prison acquired goods and services needed for the inmate population, on how and where facilities within the prison were to be expanded, on how and why new rules and regulations were created, and, often, even on issues of prison security. Phelps invited me to participate in official administrative discussions, sometimes asking my opinion, which shocked many of his staffers. He brought me to corrections headquarters and introduced me to his staff. He introduced me to those who exercised power so I could see how they made their decisions. He frequently brought outside officials and state politicians to the Angolite office to chat about the prison, the corrections system, and political affairs, regularly referring officials, reporters, and individuals seeking assistance or information to me. In doing so, he was conferring credibility upon me.

Phelps was the first of a line of wardens to sit in my office and discuss prison issues. I learned that it really was lonely at the top. It’s difficult for wardens to get honest advice from those around them. The warden is all-powerful within his prison world; it’s a rare subordinate or inmate leader who is going to disagree with him. Subordinates tell the warden what they think he wants to hear as opposed to what he needs to know.

The warden is the one official—corrupt, honest, inept, or mean-spirited—who wants his prison to run smoothly because he is responsible for everything and is judged accordingly. Most prison problems occur in mid-level management, where the operable rule too often is to avoid offending the boss and to cover your ass.

Both Phelps and Maggio spent a lot of time in my office, talking and listening. My pre-Angolite writings in “The Jungle,” The Shreveport Journal, the New Orleans States-Item, the Baton Rouge Gris-Gris, and Penthouse on the inmate economy, prison society, and veterans in Angola had led them, particularly Phelps, to feel that I had a grasp of the issues. They found it useful to have a prisoner like me as a sounding board, which is how I came to accept that they wanted to right the ship.

I realized that as long as I relied on reason and diplomacy, I could accomplish much. I had to be seen as totally trustworthy, and a useful resource. I also learned that the key to solving problems was never to present one without a proposed solution. My position allowed me to connect good people with each other, to promote good ideas and projects, and to find the resources to bring them to fruition.

I was becoming much more than an editor. The more I learned about management, politics, the decision-making process, the complaints, problems, and frustrations of personnel and management, the more my perspective broadened. I gained a greater understanding of what I wanted and needed to do as an editor. I saw I could help deserving individuals, be they employee or inmate.

Phelps and I developed a real friendship. We were drawn together for want of sympathetic understanding elsewhere. That was even more true of Maggio. He had used fear to whip personnel into shape, firing and hiring more employees than any warden in Angola’s history, increasing the number of employees nearly threefold in his first two years. As I said, he cracked down on employees, who cracked down on the inmates, which dramatically reduced Angola’s violence. But fear leads to avoidance, and there was little meaningful communication between Maggio and his employees. They had become sycophants, and he knew it. I could tell him things they wouldn’t.

He would roam through the Main Prison and then drop in on me, unable to understand why inmates didn’t approach him about problems so that he could correct them. Maggio would never admit it, but he wanted the prisoners, even more than the employees, to understand, respect, and appreciate what he was doing for them. They didn’t, not then.

With both inmates and employees avoiding Maggio whenever possible, The Angolite became the unofficial middleman for solving problems. I could cut through bureaucratic red tape by talking directly to Maggio or Phelps, so many people brought their grievances to me. Maggio was capable of brutality and callousness, but as long as he felt himself in control of the physical circumstances, he was a soft touch, a benevolent dictator, a liberal even, although he would never think of himself as one. Neither prisoners nor employees understood that.

Maggio’s desire to operate the best prison made him receptive to new ideas and improvements. He gave almost everything I asked for on behalf of the prisoners once I showed him that it posed no threat to his control or the security of the facility. He would always listen to reason, and I was able to rescue the inmate population from many harsh and unnecessary measures proposed by security officers and administrative officials attempting to impress the warden with their hard-line zeal. I had to keep both Maggio’s and Phelps’s confidence, not repeating what either told me; otherwise I’d lose their trust and my credibility, and my ability to help others.

Most of my friends were not caught up in Maggio’s massive lockups. In fact, they benefited from the changes he implemented at Angola. As model prisoners, many were able to take advantage of the Department of Corrections’ effort to relieve overcrowding. They maneuvered transfers to the minimum-security state police barracks in Baton Rouge, where there was not even a fence to keep them prisoner. Living there, they could work at the Department of Corrections headquarters as aides or chauffeurs, or at other government buildings as gardeners and maintenance men, or at the governor’s mansion, where only lifers, murderers in particular, were accepted as servants—a long-standing practice grounded in statistics showing that murder is almost always a once-in-a-lifetime event and that murderers have the lowest recidivism rate of all prisoners, as well as the wardens’ practical experience that murderers tended to be the most responsible of all inmates. Jobs in the mansion were the most sought-after in the system, because they included unchaperoned weekend passes into free society, among other privileges. And the ultimate prize for these servants was another tradition—governors would free their inmate domestic staff when they left office. Some of my closest friends, including Daryl Evans and Lionel Bowers, earned those jobs, shrinking my “family” considerably.

Maggio’s dismantling of gangs and the massive transfer of inmates out of Angola radically altered the inmate power structure. He ordered inmates to elect representatives to a revived inmate grievance committee, which, with The Angolite and the elected leaders of formal inmate organizations (such as the Jaycees, the lifers’ association, the boxing association, the Dale Carnegie club, Vets Incarcerated, and a host of other civic and religious organizations), formed the new power structure. My position as editor of The Angolite and an established inmate leader, together with my ability to get things done and my visible friendship with Phelps, made me the single most powerful prisoner in the new order. That didn’t make everyone happy. One day, an angry security officer, Major Roland Dupree, gave me a direct order to begin working in the field after lunch. Frantic, I called the warden’s office and was told by his secretary to stay in my office. As the appointed time approached, I grew increasingly concerned, because refusing to follow a direct order was punishable with time in the Hole. Just moments after Dupree came back to my office, Maggio strode up to him and declared: “You don’t mess with him. If you have a problem with The Angolite, you bring it to me—I am The Angolite.” The symbolic message conveyed in that act reinforced my status.

Phelps taught me that with power came obligation. It was a lesson that was brought home to me in a forceful way. Prisoners who violated the rules in satellite facilities were usually transferred back to Angola. Maggio required all inmates returning to Angola to work in the field hoeing, shoveling, chopping, and harvesting, whether the whip was on the winter wind off the Mississippi or the subtropical summer sun parched land and man alike. This included a large number of prisoners undergoing intensive therapy at the mental health unit near New Orleans, who would be sent back to Angola upon being pronounced cured. One of the patients, feeling his punishment was undeserved, began complaining. Although the counselors, security officials, and classification officers were all sympathetic, they told him there was nothing they could do because of Maggio’s policy.

Distraught, the former mental patient timidly knocked on my door. “I understand about it being the rule and all, but that don’t make it right,” he said in a despairing voice. “I was sick, and they sent me to the hospital for treatment. I had a good job before I left, but when I come back they stuck me in the field and wouldn’t give me my old job back. I ain’t done nothing wrong to be in the field, unless I’m being punished for going to get treated. You think maybe the penitentiary didn’t want me to go to the hospital and now they’re punishing me for it?”

“I think it’s probably just a mistake,” I said.

“It can’t be. I went to classification and security, too. They all told me that it ain’t nothing they can do for me.” He clasped his hands over his face, gulping for breath and choking back a sob. “Them white folks treat us bad out there in the field. They be cussin’ and hollering at us, calling us all kinds of names. They just mess with us, and for nothing a lot of times. It ain’t good for me. I can feel it. I need you to help me. I don’t know what to do, and there ain’t nobody else to help me. One of the security mens told me I oughta come talk to you and see what you can do. If you can’t help me, I don’t know what I’m gonna do.”

I was offended by the obvious injustice. Phelps had once said to me: “Sometimes the mere fact that you’re the only one who can do something makes you responsible for doing it, whether you want to or not.” I checked with security and classification. They said they could do nothing because of Maggio’s across-the-board policy. I sent messages to friends in various parts of the prison, asking for the names of all inmates sent to the fields upon their return from the mental health unit. I received two dozen names.

What I was going to do next was born of a gentleman’s understanding with Maggio I had made months before in exchange for his cooperation on The Angolite.

Not long after becoming warden, he visited me one night. He was congenial, as always, but to the point.

“Mr. Phelps told me that he wants you to have the freedom to operate The Angolite as you see fit,” he said. “That’s fine and good. He’s the boss. But you and I have got to reach an understanding, because while he’s the boss, he’s in Baton Rouge. Now, he can sit in Baton Rouge and give all the orders he wants to, but I’m the one who must put those orders into effect on a day-to-day basis, and I will be the one who sees to it that you get what you need to keep the magazine going as you want it. A warden has the power to make sure that if he doesn’t want something to work right, it won’t.”

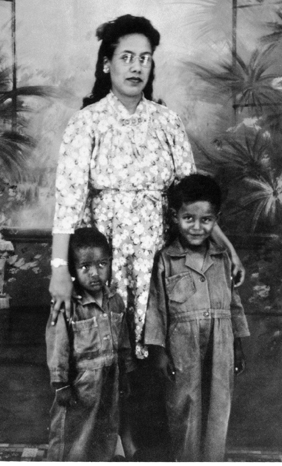

My mother, Gladys Victorian, in 1943 at age nineteen. She wanted to escape the farm.

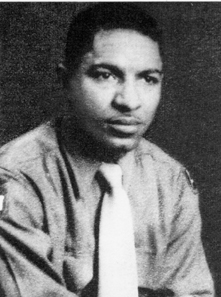

My father, Thomas Rideau. No Prince Charming, he.

My mother, a virtual slave, trapped by two kids, pregnancies, little education, no resources, and a brutal husband. I’m on the right, my brother Raymond on the left.

Southgate Shopping Center, Lake Charles, Louisiana, 1961. I worked at Halpern’s Fabrics, two doors away from the Gulf National Bank, which I attempted to rob.

Gulf National Bank, site of the failed robbery that would send me to prison for forty-four years. When the holdup went bad, I left through the back door with three employees, one of whom would die by my hand in a moment of panic.

A deputy at the crime scene where my victim, Julia Ferguson, was mortally wounded, on the outskirts of Lake Charles in 1961. The site was not protected for the ensuing investigation. Most evidence was not preserved; other evidence was altered or fabricated. This would eventually lead to my release from prison—in 2005.

Sheriff Henry “Ham” Reid brings me into the Calcasieu Parish jail through the back door around 9:00 p.m. on February 16, 1961, to avoid the mob of several hundred angry whites awaiting my arrival in the front.

District Attorney Frank Salter had been in office only a few months at the time of my terrible (and sensational) interracial crime. He made his local reputation prosecuting me for it three times and opposing my release from prison for forty years, while supporting the release of numerous other convicted murderers.

The Reception Center building at the Louisiana State Prison, which housed death row, where I arrived on April II, 1962, after being convicted of murder.

This is how I looked during my first day on Angola’s death row.

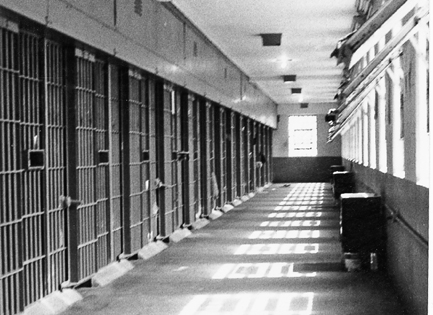

Death row, where I was incarcerated from 1962 to 1973, between trials. In 2007, this facility was replaced by a new, larger death row.

Most Angola inmates live in dormitories. Above right: A typical sixty-four-man dorm, and, left, its toilet facilities. Privacy was not part of prison life.

Inmates two abreast on the Walk, heading to the dining hall. Although the prison raised cattle and hogs, much of the meat was deemed too good for the prisoners and was sold on the open market. Cheaper food was purchased for the inmates.

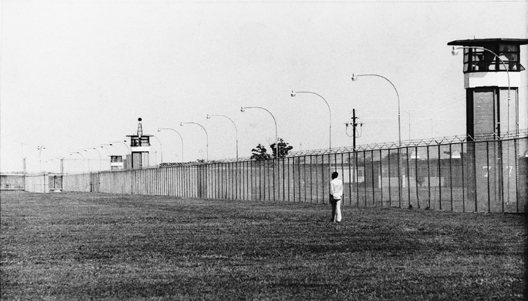

A lone prisoner walks along the fence of the Big Yard, the recreation area for half of the Main Prison’s 1,800 dormitory-housed inmates.

Relaxation takes many forms. A game of cards in the dorm.

Relaxation takes many forms. Volleyball on the Yard.

Relaxation takes many forms. Basketball teams in the gym.

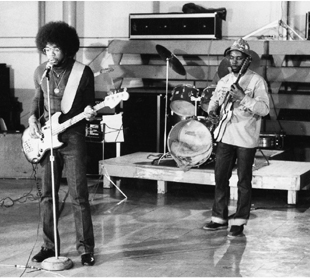

Relaxation takes many forms. Inmate musicians who entertain at internal prison events, such as the annual Angola Rodeo, and at church, civic, and political functions outside the prison.

Guards survey a cache of weapons they discovered in the Main Prison. In the 1970s, everyone had weapons, most handmade. The prevailing sentiment among inmates was that they would rather be caught by security with a weapon than by a hostile prisoner without one.

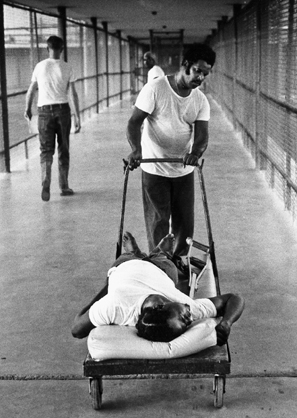

An inmate rushes another to the hospital on a buggy in the old days, before the federal court issued an order in 1975 to end the violence and improve prison conditions.

James “Stinky” Dunn, seen here in 1978, was raped and sexually enslaved by another prisoner. Slaves were treated as property—rented, traded, gambled, sold. A slave won his freedom only through release from prison or the death of his master.

In a world without females, men sought sexual relief in masturbation and from sexual slaves, some of whom were gay but most of whom were weak inmates forced by stronger prisoners to serve as women. A slave did his master’s bidding, whether that meant dancing, satisfying his sexual needs, doing laundry, prostituting, or smuggling contraband. Some embraced their prison roles as women. Most of the sexual violence in Angola was gradually ended.

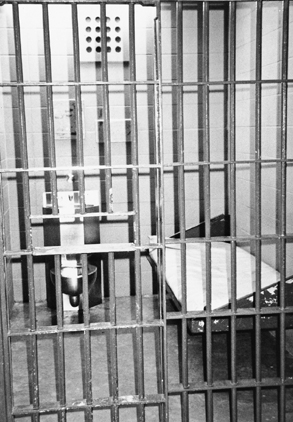

A seven-foot-by-nine-foot solitary-confinement cell, windowless, with a hatch in the door and a lightbulb on the ceiling, both controlled by a guard.

An isolation cell, distinguished by its front wall of bars, which lets the sights and sounds of humanity in. Either cell could be used for disciplinary reasons, protective custody, inmates deemed a threat to security, or the mentally ill. The length of an inmate’s stay in solitary confinement was at the discretion of authorities, ranging from overnight to, in some cases, more than thirty years.

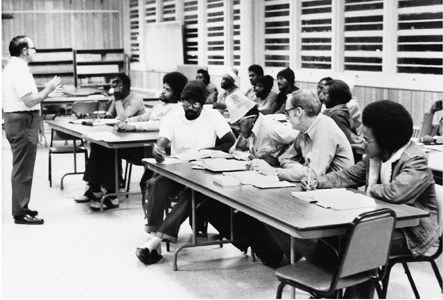

All prisoners are required to work or to attend school. Inmates study for their GEDs.

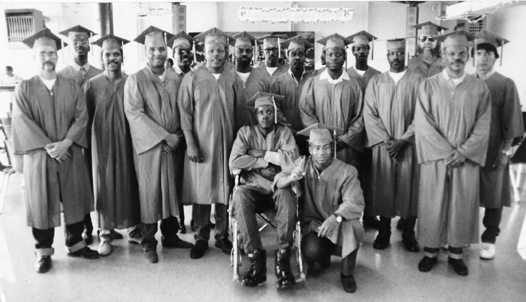

All prisoners are required to work or to attend school. Paralegal students graduate.

A guard marches laborers to the field.

Picking cotton by hand.

“Busting concrete” by hand.

Religious services conducted by inmate preachers were more popular than those led by resident chaplains, most of whom were viewed as time-serving bureaucrats. Angola has inmate-led congregations representing most Christian denominations. The Muslims, long misunderstood, became a powerful force for peace in the prison.

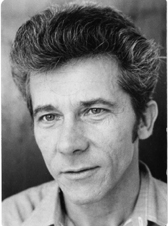

Ross Maggio, Jr., Angola warden, 1976–77 and 1981–84. Tough enough to tame the bloodiest prison in America in 1976, and tough enough to keep our prison newsmagazine, The Angolite, going when a hostile administration wanted to shut it down in 1981.

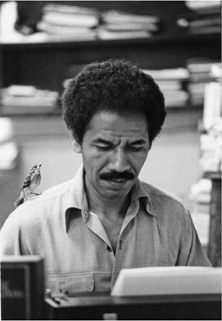

I was fortunate to be able to weave meaning and purpose into my prison life through print journalism, radio work as a documentarian and NPR correspondent, and producing television and documentary films. At my Angolite typewriter in 1977.

At the prison radio station in 1987.

Filming on the levee in 1994.

Speaking to high school students outside the prison.

“What you mean is that I could create a little problem for you with Mr. Phelps, but you can create a lot of big ones for me here,” I said.

Maggio grinned. “Another thing you want to keep in mind: If a warden doesn’t want a man to get out of prison, he’s not gonna get out, and it doesn’t matter who asks the parole and pardon boards to turn him loose.” I knew that to be true.

I asked, “What kind of deal do you want to make?”

“Well, not so much a ‘deal’ as an understanding,” Maggio said. “I’m not talking about censoring anything. Mr. Phelps doesn’t want censorship. He wants you to be free to write what you want, and that’s okay with me.” Maggio knocked the ashes from one of the half-dozen Roi-Tan cigars he smoked daily. “But you’re going to have more freedom to move and learn things than any other prisoner—and most employees—in this penitentiary, and common sense tells me that you will run across problems that I might not know exist. It’s how you’re going to handle that information that I’m interested in. If you’re just looking for a sensational story to scandalize the prison and make me and my men look bad, then we’re going to have a problem. And it’s not going to be good for anyone if there’s a legitimate problem that I could have solved but can’t solve once it comes out. I’ve got to defend my men and their actions, and I’m going to do that.

“All I ask is that when you come across a legitimate problem that affects the prison, let me know about it. I’m not talking about snitching or giving me information about prisoners or other people’s business. I’m never going to ask you anything like that. I’m simply talking about the kind of problems that affect the institution and my administration of it. You give me a chance to solve it first, then you can write whatever you want, stating that the warden’s office either solved or didn’t solve the problem. Then you’re not going to have any difficulties with The Angolite. In fact, I want to see you and the paper do a good job because it’s to my benefit.”

What Maggio wanted was reasonable, and his wanting to defuse problems before they became public gave me an opportunity to approach him for solutions. Once a problem was brought to Maggio’s attention, he would act on it.

So to deal with the former mental patient’s problem, I called Frank Blackburn, associate warden for treatment. I explained the problem and said: “The public would never stand for this. There is something particularly offensive about sending a mentally ill person to a hospital for treatment and then punishing him for it.”

“We didn’t put those people in the field for punishment,” Blackburn replied.

“I know—you put them out there to teach them good work habits,” I said. “You can paint this thing any color you want, but there is no way you can justify sticking mental patients in the most stressful work detail in the prison.”

“Warden Maggio gave the order and it’s to be applied straight across the board—no exceptions. It’s what he wants, and he’s the warden.”

“If this thing leaks to the news media,” I said, “he’ll get front-page coverage from New York to Bangkok. I’m sure he’d rather have you make logical exceptions.”

“Well, Rideau, I don’t have the authority to make an exception to Warden Maggio’s orders.”

I already knew that. “Then maybe you could take the policy to him and point out the need to make an exception. My guess is that when the media starts asking questions, his first question to you will be: ‘Why wasn’t I told about this?’”

After some more back-and-forth, Blackburn told me to send the names to him. “I’ll talk to Warden Maggio,” he said.

The problem was promptly resolved, and the former mental patients were reassigned to less stressful jobs.

And so I became kind of an unofficial ombudsman for the prison, solving many inmate problems through low-level prison officials who preferred to resolve the issues themselves rather than have me take them to Maggio or expose them in The Angolite. Indeed, many employees came to welcome my intervention. I liked being helpful, and I also liked the fact that my role as Angolite editor freed me from the deadening regimentation of prison routine. Unlike the lives of those who labored at difficult or mindless jobs, mine was determined rather by the events, intrigues, and problems of the day.

Instead of relieving overcrowding by releasing the old, infirm, and handicapped among its mostly black inmate population, as other states did, Louisiana, flush with oil money, instead chose in 1976 to build its way out. The state spent more than $100 million to construct and expand facilities, creating a lucrative prison-building boom for politically connected architects, contractors, and builders. Camp J, Angola’s new maximum-security disciplinary cellblock, opened near the end of May 1977, just in time to take in a couple hundred of the seven or eight hundred rebellious fieldworkers staging a “work slowdown.”

I rushed to the Control Center Gate, which led to the Big Yard, when I heard about the disturbance, because I wanted to photograph it. I was stopped by a guard who sent me back to the Angolite office. He was following the warden’s instructions. Furious with Maggio, I complained to Phelps. He already knew about it.

“You probably won’t appreciate this, but what Ross did was for your protection,” he said. I told him I didn’t need to be protected from the inmates, that Maggio did it to protect his guards from getting their picture taken doing something they didn’t want anyone to see.

“A criminal will do just about anything to prevent exposure and punishment,” said Phelps. “What makes you think a guard will respond any differently to your pointing that camera at him when he’s beating an inmate with a baton, regardless of whether he’s justified or not? Guards are like people everywhere: They don’t always follow orders or obey rules or laws. Ross wasn’t protecting them from you, but you from them. I can assure you those guards would have taken that camera from you, destroyed it, and probably hurt you very badly in the process. Freedom of the press is an ideal we’re trying to make work in here, but our first priority is to protect life—in this instance, yours. You just confirmed that you weren’t even aware of the danger you were about to walk into. Ross did the right thing.”

I asked him if that meant our agreement that I wouldn’t be censored was subject to the whim of the warden. He responded that there could be no free press if I was lying in a hospital bed. “In order to accomplish anything, both you and The Angolite have to survive,” he said. “You know, Wilbert, people who have power don’t always cooperate with the press. In fact, they will do almost anything to protect themselves from bad press.” He told me publishing does not occur in a vacuum, and at times I would have to be creative in order to do what the power-holders didn’t want me to do. He said publishers, editors, and reporters all over the world confront this same problem every day. He also pointed out that journalists didn’t always have cameras. “But you still have the power of the pen,” he said, “and the freedom to do what any good journalist would do—backtrack, investigate what happened, interview inmates and guards who were involved, then paint a word picture of what took place for your readers. Quit complaining—do your job.”

My frustration at having been barred from covering the disturbance vanished as Phelps’s lecture sank in. He had given me a broader context in which to see myself and my work. I wasn’t just a prisoner who had been handed certain rights; I was a real journalist with a real job to do. Like the best journalists, I would sometimes have to be resourceful to surmount obstacles to a story. This new view of myself shaped my work in all the years to come.