A lot like human shoes (though definitely less stylish), horseshoes have been protecting feet for centuries.

The inventor of the horseshoe is lost to history, but the idea has been around for a long time. Asian horsemen from the second century BC put booties made from hides or plants on their horses’ feet to protect them from injury. And sometime after the first century AD, the Romans introduced leather and metal “hipposandals,” which attached to a horse’s hooves with leather straps.

Over the next few hundred years, there were some references in literature to horseshoes—in particular, a Koran from the seventh century talks about cavalry horses that “strike fire by dashing their hoofs against the stone.” But it wasn’t until 910 that the horseshoe showed up definitively in print: Byzantine emperor Leo VI mentioned horses’ “crescent-figured irons and their nails.” By about 1000, metal horseshoes were common in Europe and Asia.

One of the reasons for the shoes’ popularity was that iron had become cheaper and more plentiful by the 11th century. Also, soldiers heading off on the Crusades liked large Flemish horses, but the animals had flat, weak feet (because they lived mostly in damp areas). So horseshoes were necessary to protect their sensitive hooves. In fact, horseshoes became such an important commodity that, in some places, they could be used as money. Horseshoes remained mostly a military accessory, though, until the 13th and 14th centuries, when improvements in manufacturing meant that shoes could be mass-produced and bought ready-made.

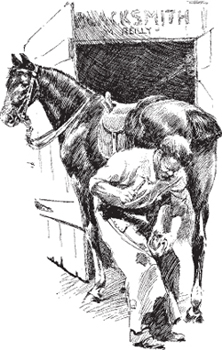

By the 1600s in Europe, horseshoeing was a full-fledged business. Back then, farriers in Great Britain and France were also horse doctors. During the 17th century, though, they stopped practicing equine medicine and became fulltime blacksmiths.

With the onset of the Industrial Revolution, horseshoe use and production grew even more. The first machine to cast shoes en masse appeared in 1800, but the first patent for a horseshoe-manufacturing machine was issued in 1835 to New Yorker Henry Burden, who could make 60 shoes every hour. In the 1860s, the Union army had its own machine to make horseshoes, an invaluable tool that gave their cavalries an advantage over the South during the Civil War.

Little has changed in the horseshoe’s basic design since then. Farriers still use the U-shape horseshoes that they nail (or sometimes glue) onto the horse’s hoof. Steel and aluminum are the most common metals used, but shoes can also incorporate rubber, plastic, magnesium, titanium, and copper. Sports like jumping, eventing, and polo require strong, durable shoes made from steel, but race-horses need light feet, so aluminum is the preferred metal for the track.

Not everyone thinks horses need shoes, though. In the wild, of course, horses go barefoot and mostly do fine—natural wear helps to toughen and trim their hooves. And just because shoeing has a long history and has become the most mainstream method of hoof care, say the antihorseshoers, there’s no reason not to strive for a more natural lifestyle.

Officially called the “barefoot horse movement,” supporters of this cause have been around for decades and argue that when horses’ feet are trimmed and cared for properly, they don’t need shoes. The type of terrain the horse trains on is the most important factor. And besides being more comfortable for the horse, the benefits of going natural include a lower risk of laminitis and navicular syndrome, both of which can make horses lame and, in some cases, can threaten their lives.

Going from shod to barefoot can be a long process, and horses have to spend at least a year training on natural surfaces like grass and dirt before they develop tough enough feet to walk on hard surfaces like cement and asphalt. But once their feet adapt, they can go almost anywhere shod horses can. (Hoof boots can provide protection during the transition.)

Gypsy horses are docile and sturdy, qualities that have earned them the nickname “golden retrievers with hooves.” About 100 years ago, nomadic Roma gypsies in England and Ireland started breeding these horses specifically for that temperament. The Roma needed low-maintenance draft horses to pull their wagons. And they wanted their horses to reflect their peaceful culture. Aggressive horses were usually sold to maintain the breed’s friendly nature.

Today, gypsy horses go by several names: Irish cobs, Irish tinkers, gypsy cobs, and others. But they’re all the same, sturdy draft horses, recognizable by their silky tails and manes, feathered legs, hardiness, and gentle disposition.