Grooms are perhaps the hardest-working laborers at the racetrack. They are the trainers and jockeys’ eyes and ears and the horses’ best friends. But they’re also among the industry’s least-appreciated professionals.

In the racetrack pecking order, grooms generally rank just above stable hands and exercise boys and are rarely rewarded for the relationships they develop with their horses. A few lucky grooms might get a percentage of a horse’s winnings—maybe 1 percent—in addition to their wages (usually between $400 and $600 per week), but that’s the exception. Long hours, huge responsibilities, modest wages, and no job security are the norm.

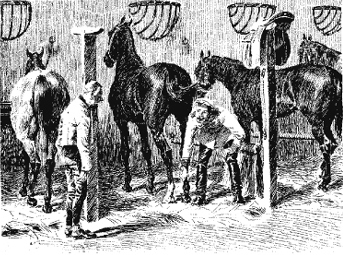

Some grooms have just one equine charge (usually a high-profile racehorse), but most are responsible for six to eight horses. Their daily chores include preparing feed, monitoring diet, and tending to aches, pains, bruises, and strains. They check a horse’s shoes and tack for wear, prepare the animal for exercise and races, and advise the trainer and jockey. Because the horse’s health and performance are paramount, everyone depends greatly on the groom’s close attention.

Triple Crown winner Secretariat and his groom Eddie “Shorty” Sweat were buddies. Secretariat was not a “people” horse. He was high-strung, demanding, and intelligent, and often nipped passersby. Sweat calmed his nerves, soothing his anxieties with quiet conversation. He even sometimes slept on a cot outside the racing champion’s stall.

Every morning, horse and groom greeted each other with a shake—Sweat’s hand and Secretariat’s outstretched tongue. The two times that Secretariat finished out of first place, the horse stood facing the back of his stall until Sweat came by to bolster his spirits. And whenever Secretariat flew cross-country for races, Sweat was responsible for loading him onto the plane and accompanying him on the journey . . . at his side the whole time.

Sweat also shared a little of Secretariat’s spotlight. After the 1973 Kentucky Derby, Sweat got to come out from behind the backstretch to walk Secretariat into the winner’s circle. And when a life-size bronze statue of Secretariat was unveiled at the Kentucky Horse Park, it included jockey Ron Turcotte aboard and Eddie Sweat leading the horse.

Susan Esseltine, from Ontario’s Western Fair Raceway, won the title of Groom of the Year in 2006. A well-known figure around the paddock, she’s spent 30 years at the track. Her father ran Western Fair’s tack shop, and at 15, Esseltine started mucking stalls. She became a groom soon after.

Esseltine usually works at least 12 hours a day. She begins at dawn, and if one of her horses runs on a night racing card, she may not have the horse paddocked before 1:00 a.m. Esseltine is particularly remarkable, though, because she’s also fighting leukemia. Each week she takes a day off to obtain treatment at the local cancer clinic, yet as the next day dawns, she’s back at the track—business as usual. Esseltine may not make lots of money at her job, but she and other grooms sign up for the other benefit: the relationships they develop with the horses in their care.

The ancient Greeks were avid horsepeople who introduced four-horse chariot races to the Olympics in 680 BC. Men started competing in the Olympics on horseback around the same time.