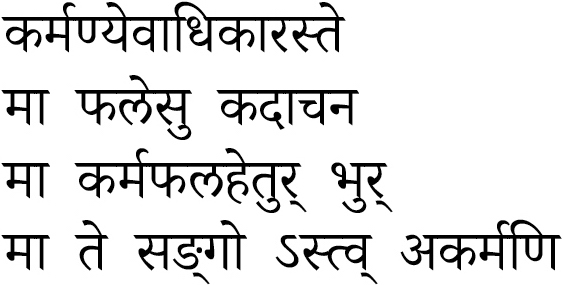

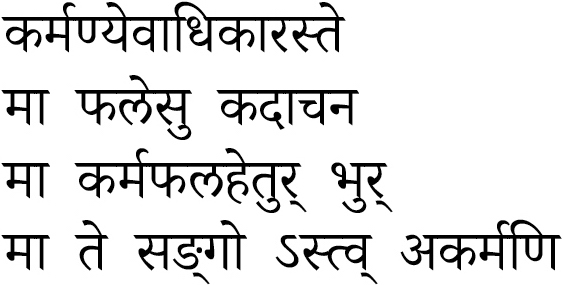

Your right is to action alone; never to its fruits at any time. Never should the fruits of action be your motive; never let there be attachment to inaction in you.

—Bhagavad Gita, book II, sloka 47

Seven or sevenish

Playwright August Wilson and I always met at 7:00 P.M. at the Broadway Bar and Grill, which was just a short walk from his many-roomed home on Capitol Hill in Seattle. We looked for the smokers’ section at the rear of the restaurant in a spacious, dimly lit room with two televisions mounted on the peach-colored walls. He would arrive as tidily dressed as ever, his demeanor courtly and dignified, even gracious, with his salt-and-pepper goatee neatly trimmed, and wearing a stylish, plaid cap on his balding head. (He once told me, “I should just stop going to the barbershop.”) We were two old men with a combined hundred-plus years of American history on our heads, only three years apart in age, and raised in the 1940s and ’50s by proud, hardworking parents. You might say that for fifteen years these eight- to ten-hour dinner conversations at the Broadway were our version of a boys’ night out. It was a lively, laid-back place filled with young people, straights and gays, students and Goths, and much nicer than the dangerous place we would end up in before this evening was over.

After a handshake and a hug, we would sit down, order organic Sumatra French Roast coffee and a big plate of chicken nachos with black beans, olives, and guacamole. Then we began the ritual that defined for me our friendship. We always tried to remember to bring some kind of gift for each other. It was a ritual of respect, generosity, and civility. The presents we gave each other were always art, or about art, and each represented our lifelong passion for the creative process. Because he knew I was a cartoonist and illustrator, he would give me, say, the tape of a documentary showing Picasso at work, or The Complete Cartoons of the New Yorker and The Complete Far Side by Gary Larson. I, in turn, would give him a limited-edition, facsimile reproduction of one of Jorge Luis Borges’s short story manuscripts presented to me during a State Department–sponsored lecture tour in Spain, because Borges, Amiri Baraka, Romare Bearden, and the blues, or the “Four Bs” as August called them, were the major influences on his work.

Eight o’ clock

Finally, after we’d examined and discussed our gifts, and the waiter, a thin young woman, leggy and tattooed, with bright red hair and a nose ring, returned to top off our coffee for the second time, we’d relax and let our hair down. This experience, we both knew, was extremely rare in the lonely, solitary lives of writers, especially those considered to be successful by the way the world judged things, so we sometimes looked at each other as if to say, “How did you happen?” This unstated question was filled with equal parts of curiosity and affection, partly because he and I belonged to an in-between, liminal generation that remembered segregation yet was also the fragile bridge to the post–civil rights period and beyond; and partly because American culture had changed so much since we began writing in the 1960s, growing coarser, more vulgar and selfish year by year, distancing itself from the vision of our parents, who were raised to value good manners, promise keeping, personal sacrifice, loyalty to their own parents and kin, and a deep-rooted sense of decency. On the stage, his goal was to make audiences respect their hardscrabble lives and his own. This new era of hip-hop, misogynistic gangsta rap, and profanity-laced ghetto lit sometimes made our souls feel like they needed to take a shower. He told me often that if he ever met the Wayans brothers, he planned on slapping both of them silly.

“You know what?” I could tell by the tilt of his head that he felt playful tonight. “When I was out of town for rehearsal these last few months, I’d leave my hotel room, walk over to the theater, and every day I’d see the same man panhandling on the street. He stopped me every day, and every time he had something new for me, so I had to give him some money. For example, one day he pointed down at my feet, and he said, ‘I know where you got those good-lookin’ shoes. I can tell you exactly where you got those fancy shoes.’ ”

The man August was describing could easily have been an antic character in one of his plays.

“You got ’em on your feet,” he said. “But I know somethin’ else, too. I know the day you were born. I can tell you the very day you were born, and I won’t be wrong or off by more than three days.”

August was born on April 27, 1945.

When he asked this fellow what day he was born, the man cackled and said “Wednesday.”

And so it went for fifteen years of pas de deux. Sometimes we’d lean into the table to hear each other better when our voices were blurred by the clatter and clang of dishes and swirl of laughter and conversation from other tables around us, talking about our hopes for our children, our wives, our agents and lawyers and business partners, the next story we planned to write for Humanities Washington’s yearly Bedtime Stories fund-raiser, a passage I translated for him that he liked from the Bhagavad Gita and our works in progress—Gem of the Ocean and Radio Golf for him, the novel Dreamer for me. But for the most part, and because I’m Buddhist, I did the lion’s share of listening. Also because my middle-class life in the Chicago suburb of Evanston had not been half as hard as his in the Hill District of Pittsburgh. He wanted someone to listen as he spoke about his life, all the experiences and ideas not always in his plays but which were, in fact, the background for his ten-play cycle. Over fifteen years, I heard about his biological father, Frederick Kittel, the German baker who was always absent from his life, and his stepfather, an ex-convict who spent twenty-three years in prison for robbery and murder. He adopted his mother’s maiden name, Wilson, in rejection of his German father; he began using his middle name, August, when a friend told him not to let anyone call him by the first name he used throughout childhood, which was Freddie. August told me that when he entered the newly integrated public schools of Pittsburgh, he was attacked by a gang of other kids; the principal had to send him home in a taxicab to protect him, but all he could do was ask over and over, “Why? Why are they trying to hurt me? What did I do?” And I learned about why he dropped out of high school his freshman year when a black teacher accused him of plagiarizing a twenty-page term paper entitled “Napoleon’s Will to Power” and refused to apologize.

Out of school at age sixteen, he worked at menial jobs. “I dropped out of high school, not life,” he often said, and that was true: he may not have been a formally trained intellectual, but he was an organic one, who read shelf after shelf of books at his local library, and dreamed of becoming a writer. No, he was not in school, but he did have a reliable and constant teacher: suffering. “If you want to be a writer,” a prostitute once told him, “then you better learn how to write about me.” He did take her advice. He also joined the Army, and was doing quite well, but, being a proud and hot-blooded young man, he left when he was told he was still too young to apply for officers’ training school. There was a year in his life when he was a member of the Nation of Islam, an organization he joined because he hoped to win back the love of his Muslim wife after she unexpectedly left him, taking their daughter and stripping their home clean of every stick of furniture. Entering those barren rooms, said August, was so devastating and heartbreaking that this shock of emptiness washed the strength from his limbs. How many times had his heart been broken? He could not remember the countless disappointments. Like so many writers and artists I’ve known, his art was anchored in lacerations and a latticework of scar tissue. All that raw pain, poverty and disappointment, denial and disrespect—-as when critic Robert Brustein said he had “an excellent mind for the twelfth century”—all this he alchemized into plays that, before his death in 2005, earned him two Pulitzer Prizes, eight New York Drama Critics’ Circle Awards, a Tony Award, an Olivier Award, a National Humanities Medal presented by Bill Clinton, a Broadway theater renamed in his honor, and twenty-eight honorary degrees.

Yet the public could know only the media-created surface, not the subterranean depths, of any artist. Every time you sat down to create something your soul was at stake. Every page—indeed, every paragraph—had been a risk. Every sentence had been a prayer. So when speaking of those honorary degrees, August told me that he recently came across one of them in his attic and suddenly burst into tears because he couldn’t for the life of him remember this particular award that was so dear-bought with his own emotional blood. What no one knew of, or could know, was that after every one of his ten plays opened, he fell into a period of severe depression that always lasted for two solid weeks.

He talked freely because he knew I understood these things, how despite the strong black male personas our past pain made us present to the world, we were far more sensitive than we could ever dare show (and had to be sensitive and vulnerable in order to create), with the external world being no more than raw material for our imaginations, and that meant we were eccentric: he didn’t drive, or do e-mail, or exercise, and if someone walking a dog came his way on the sidewalk, he would step into the street because dogs frightened him, why I can’t say. More than once he shared with me his fantasy of finishing his ten plays and telling the world he was retiring. Then, when the reporters went away, the phone stopped ringing, and he vanished from public view, August planned on sitting on his Capitol Hill porch reading piles of books he never had the time to get to, playing with his young daughter, and writing without interruption or distraction for a decade. When that ten years ended, he said, he planned to emerge from seclusion like Eugene O’Neill after his decade away from the spotlight, and with plays that would be as powerful and enduring as The Iceman Cometh, Long Day’s Journey into Night, and A Moon for the Misbegotten. He also hoped one day to write a novel.

Those nights at the Broadway Bar and Grill, he needed to talk about things like this. And sometimes he expressed a fear that shook me to my very foundations.

Midnight

At some point during our conversations his thoughts always turned to the ambiguous state of black America. Like the narrator of Charles Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities, you could say for black America that “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” August and I were doing well, he said, but he couldn’t forget the fact that Broadway theater tickets were expensive and 25 percent of black people lived in poverty, and therefore never saw his plays. He said there were too many black babies born out of wedlock and without fathers in their homes. Too many young black men were in prison, or the victims of murder. Too many were living with the HIV virus. It was as if forty years after the end of the Jim Crow era, black America was falling apart.

“So let me ask you a question,” he said. We’d long ago finished our entrées (the Dungeness crab sandwich for me, the grilled cedar plank salmon for him) and had lost count of how many times the waiter had filled our coffee cups. The last four hours had passed as if they were only fifteen minutes. Only a sprinkling of people remained in the rear of the Broadway Bar and Grill, which was less noisy now so his voice was clear against the background of music drifting from the front room. “Do you think any of it matters?”

“What?”

“Everything we’ve done.” His eyes narrowed a little and smoke spiraled up his wrist from his cigarette. “Nothing we’ve done changes or improves the situation of black people. We’re still powerless and disrespected every day—by everyone and ourselves. People still think black men are violent and lazy and stupid. They see you and me as the exceptions, not the rule.”

“You don’t see any real changes since the sixties?”

“No,” he said. “Not really.”

For a moment I didn’t know what to say. I knew he meant all this. You could see it in his plays, that sense of despair, futility, and stasis. If he was right, then I wondered, What good was art? And his words took the philosopher in me to an even deeper dread. If you paused for just a moment and pulled back from our minuscule dust mote of a planet in one of a hundred billion galaxies pinwheeling across a 13-billion-year-old universe that one day would experience proton death, then it was certain that all men and women had ever done would one day be as if it never was. I wondered: Had we then wasted our lives? Was man, as Sartre put it in Being and Nothingness, “a useless passion”?

Two o’clock

I was about to press him on this point about the social impotence of art and, by virtue of that, ourselves, but now our waiter was standing beside us.

“I’m sorry, but you guys are going to have to go. We need to close.”

We paid our bill, left a generous tip, and stepped outside to the empty street, talking on the wide strip of cement for another hour. Both of us realized that this business of whether art mattered beyond the easily forgotten awards and evanescent applause was an issue that had reenergized us—or maybe it was the coffee we’d been drinking for the last seven hours. Also, we both knew it was still too early to go home to our wives. Accordingly, August suggested we find a twenty-four-hour place so we could keep on talking. The only restaurant open was a nearby International House of Pancakes. We climbed into my Jeep Wrangler and drove south on East Broadway to Madison Street, where I hung a left and after one block downshifted into the helter-skelter of a parking lot. Something was wrong here. There was a blue-and-white police car outside IHOP and a cop was talking to one of the employees wearing a gray, short-sleeved shirt and a blue apron. As nearly as I could tell, something had happened just before we arrived, perhaps a robbery, but we didn’t know for sure. Confused but not ready to give up on the night, we stepped around the police car and went through the double doors inside.

Three o’clock

The dining area was a brightly lit rectangle with two ceiling fans turning slowly and booths arranged along the walls and down the middle. Unlike the Broadway, the customers in IHOP at this hour were night hawks, the people who slept all day and only ventured out after dark: a group that may have included the occasional prostitute, gangbanger, pimp, or drug dealer. No one seemed to recognize either of us as a famous writer. A fidgety waiter seated us in a booth behind the cash register. I saw the police car pull away. Inside, the air felt tense and fibrous. The other patrons were poker-faced and skittish, speaking in whispers, watching for something, their eyes occasionally flashing with fear. August noticed this, too, but he said nothing. He was more at home in this setting than I was. It was a replay of Pittsburgh’s Hill District. He knew what to expect. I didn’t. When the waiter brought us two cups of flat, brackish coffee, we tried to resume our conversation, but try as I might, I couldn’t concentrate on his words. And what happened next I had not expected. The front doors opened, and two young men wearing lots of bling—the one in front compact in build, the one behind him tall and thin like Snoop Dogg—walked straight past a waiter who tried to seat them, and headed toward a table in the back where two women sat with a chuffy-cheeked young man whose complexion was pitted and pockmarked. The first man, handsome and clean-timbered, with the plucky confidence of the actor Ice Cube, began singing at the man who was seated. But wait. It wasn’t singing. It was rap. A kind of rhymed challenge. I couldn’t make out the words. Being an old gaffer, I could never keep up with the japper of fast-talking rappers, but everyone in IHOP sat listening, frozen in their seats and afraid of this situation. Then he and his companion laughed and walked back to the lobby. A moment later, the man with bad skin stood up, clenching and unclenching his fists, and he walked with long strides to the lobby, too. I could tell they were talking. A few seconds passed. Then all at once I heard a tumult, a crash, a sound of shattering glass. I half stood on the red seat beneath me to see better. The first two men sailed like furies into the third, smashing wooden high chairs over his head. He jackknifed at the waist and I heard a flump as he hit the floor. The other two stomped his fingers and kicked his face to a pulp, breaking bone and cartilage. Then they fled. Their victim staggered weakly to his feet, his breath tearing in and out of his chest, blood gushing from his lips. Then he, too, reeled out into the night.

The fight was over in ten seconds. All that time I’d been holding my breath. Finally, I faced round to August. But he was gone. Not too surprisingly, I picked him out in a crowd of customers who had wisely scrambled toward the exit at the back of the room. The moment the fight started, his old Pittsburgh instincts had kicked in, telling him to duck for cover in case someone started shooting.

Four o’clock

It took the police only a few minutes to return to IHOP. The restaurant’s manager apologized to the patrons for the incident, which surely would be reported in the next day’s Seattle Times and seen as just more bad PR for black people. The manager said we didn’t have to pay for anything we ordered. We felt shaken by what we’d seen. Forty years earlier, we could have been those young men destroying each other. I looked at him; he looked at me, and perhaps we both thought at the same time, How did you happen?

It went without saying that we figured it was finally time to go home to our wives and children.

We stepped carefully around pools of blood, broken glass, and splinters of wood at the entrance, and returned to my Jeep in the early morning light, the air full of moisture. I said little. A strong rain wind slammed into the Jeep as I drove him home, making me hunch over the steering wheel. Finally, August broke the silence. He said, “People always ask me why black folks don’t go to the theater. I try to tell them we’ve got enough ritual and drama in our lives already.”

I stopped my Jeep in front of his house. We shook hands, and promised to get together again soon. Since his death, I often replay in my mind the image of America’s most celebrated black playwright slowly climbing the steps to his front door; and at last I understood in what way decades devoted unselfishly day and night to art really mattered. The love of beauty had been our lifelong refuge as black men, a raft that carried us both safely for sixty years across a turbulent sea of violence, suffering, and grief to a far shore we’d never dreamed possible in our youth, one free of fear, and when his journey was over laid him gently, peacefully to eternal rest.