4

a woman of the world

Paris, 1764

Living on the far side of the globe, with family and work commitments, I do not get to Paris very often and I do not always get the chance to do the research I would like while I am there. But this time is different. I have a month in France to complete my research in Burgundy, Paris and Brittany – the longest I have ever been away from my family. Just getting there eats up precious time. Even the quickest flights take 24 hours, flying at 900 kilometres per hour. It feels like an eternity and I binge watch a miniseries of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables to pass the time.

In 1764, the journey from Toulon-sur-Arroux to Paris took considerably longer and was much less entertaining. Four days with good fortune and fair weather. Not even the pretty little villages and neat vineyards viewed from the well-upholstered comforts of a six-seater diligence offered any relief from the fatigue, boredom and cold. Wooden wheels bounced aching bones over potholed roads, and the only opportunity passengers had to relieve their swollen legs was when they had to march through the snow alongside the laden carriage.

The diligences stopped regularly at inns along the way, allowing travellers and horses to eat, drink and sleep. The food and hospitality varied from exceptional to atrocious. By the time they reached Charenton, where coaches from Burgundy waited for customs approval to enter Paris, the travellers were grateful to step wearily from their carriage.

For a naïve provincial visitor like Jeanne, Paris must have been a revelation: a city of over half a million souls crowded along a wide river. Warehouses packed the banks of the Seine. The towers of Notre Dame rose heavenward in the distance, and everywhere there were buildings and people: a sea of humanity, rising and falling, ebbing and flowing, through cluttered streets.

The city was marked by extraordinary wealth. Prosperity poured from fountains, palaces, gateways and façades. The well-to-do promenaded in their fine gilded carriages and glossy steeds. But those not blinded by gold must have noticed how the river, roads, shops and ships hummed with desperate industry. Vendors threw their hoarse cries for apples, coffee and firewood into the air, hoping to catch some coin. Washed into every corner and every doorway were the discarded, the damaged and the forgotten – the elderly, the sick and the injured. The voices of a hundred provinces all mixed and merged into one Parisian patois, filling the narrow streets of the Île de la Cité, the markets of Les Halles and the laneways of Faubourg Saint-Antoine with their unheeded misery.

Once cleared to enter the city, the travellers crossed the river towards the Left Bank, passing into the quieter, leafy streets of the parish of Saint-Sulpice, near the royal gardens and the Sorbonne. Construction had already started nearby on another grand domed church destined to become a Parisian landmark, this time dedicated to Sainte-Geneviève.

Commerson rented a second-floor apartment here, from a Monsieur Legendre, in Rue des Boulangers – number 15 on the second floor. Old maps and a painting for a later resident reveals that the top floors on both sides of the street had sweeping views across gardens to the north and south. Ground-floor residents enjoyed access to a large rear garden. Jeanne would have collected water from the well in the sandstone paved courtyard, and bought bread from the bakers who gave the street its name, and household supplies from the small shops and street stalls that crowded the narrow lane below.

How did a pregnant young peasant woman from the provinces find life in the middle of such a big city? Did she struggle to understand, to be understood, to lose the Bourguignon-Morvandiau dialect she had grown up with? Or had she already heard stories from Morvan wet nurses who suckled Parisian babies at their breast? She could have heard enticing stories from one of the Foundling Hospital agents patrolling the countryside in search of suitable nursing mothers for the wealthy of Paris. Jeanne may well have known a great deal about Paris before she arrived.

Perhaps she was not so much escaping from scandal in Morvan, as arriving in a city of opportunities.

It takes time to reach a point of departure. These things do not happen overnight. Even after Caliph was launched and afloat in the bay, it took some years before my family’s voyaging began. Caliph was inspired by Joshua Slocum’s Spray, an old gaff-rigged Chesapeake Bay oyster boat that Slocum rebuilt from a derelict state and ultimately used to become the first person to sail single-handed around the world in 1895–98. His choice of vessel proved inspired: incredibly easy to handle, stable in rough weather, comfortable and roomy. Most importantly, the Spray’s long keel and unique combination of sail plan and lines meant that the boat held its course without the need for constant alteration by the helmsman – perfect for a solo voyage.

Like Jeanne, Slocum is known for being a first in circumnavigation, in his case sailing alone. Like Jeanne though, the full picture is often missing, the rugged male solo sailor eclipses the family man of earlier voyages, who sailed with his wife and several children.

Caliph too was built for family voyages, but it was not a replica of the Spray. For a start, the boat was made of steel, not wood, and its stern was round, rather than broad and square. The rig varied over time as my Dad tinkered with the design, starting as a ketch with a Bermuda mizzen and ending as a yawl with a small lugsail aft. But Caliph proved a comfortable and spacious home: safe, solid and reliable.

For a while, I commuted to school via dinghy then pushbike each morning. In the afternoon I called my parents on a VHS radio to collect me from the beach. When I was eleven, I left the local primary school and collected a large box of schoolbooks from the post office. My days as a student of the Correspondence School began, launching a lifetime of regulating my own workload and time. It proved the perfect apprenticeship for a life as a researcher and as a writer. I was ready to go anywhere.

But still there was more to do. Along with modifying the rig, our rebuilt vintage engine needed replacing. The internal layout was remodelled and eventually I moved from my focsle bunk with its porthole view to a spacious 1-by-2-metre cabin with a fold-out desk, bookshelves and copious cupboard space. An Alaskan filmmaker hired our boat to record white pointer sharks at Dangerous Reef in Spencer Gulf, and we spent months with the decks covered in equipment, horsemeat and whale oil, with a crew of off-season abalone divers. Our cat feasted purring on piles of bait but fled from the sharks. The white pointers circled in dark shadows around the boat, launching sudden attacks along the hull and spraying shattered teeth that glittered as they slowly sank in the water. The living conditions were rough, not great for schoolwork, so my parents sent me off to stay with my grandparents until our voyage was ready to begin.

Unlike past visits to Paris, this trip is not a holiday. This time I have coordinated my research with an old friend, Carol Harrison, a French historian from South Carolina who visits Europe regularly for her own research. We met as graduate students and have worked together before on French Pacific navigators. She is keen to help me negotiate both the archives and the landscape of old Paris.

The streets of eighteenth-century Paris bore little resemblance to the wide straight boulevards and uniform rows of Haussmann buildings in mansard bonnets that feature on Parisian postcards today. Carol tours me through the old city tucked behind the one reconstructed at the behest of Napoleon III during the Second Empire, her expert historical commentary colouring the streetscape with vanished lives and activity.

In the dark backstreets of the Marais, haphazard old buildings lean over narrow cobbled lanes. The roads twist past tiny shopfronts, and heavy wooden doors open here and there onto light-filled courtyards. Glass-fronted ground-floor apartments are topped by progressively diminishing floors culminating in tiny maids’ attics. These lanes wind like tributaries down to the banks of the Seine, which once formed the major thoroughfare through the city.

In Jeanne’s time, the river was crowded with barges, punts, ferries and dinghies. Livestock, horses, food and wine all flowed up and down the Seine, connecting the French hinterland to the regions and to the ships waiting in distant harbours to transport goods overseas. Not just transport though. Laundry boats also crowded the river, cleaning the city’s dirty linen in its waters. The powerful shoulders of the washerwomen pounded the clothes with wooden batons, squeezed the last drops from limp sheets, seared them with flatirons and hefted washing baskets aloft.

Like the streets of the Marais, Rue des Boulangers is also old. It has followed the same narrow crooked path since 1350. Today, one end has been cut off by the busy thoroughfare of Rue Monge, constructed in the nineteenth century to improve access across Paris. The old lane is so narrow that the windows of the upper-storey apartments seem to stare at each other with stony-faced indifference. Stormwater and debris tumble heedless down the centre of the cobbled street towards a small park and market square. And beyond, the road leads directly to a side gate into the Jardin des Plantes, which surrounds the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle. These institutions, then the Jardin du Roi and Cabinet du Roi, were where Commerson looked for work, and where his archives and remaining collections are now stored.

Carol has rung and arranged a meeting with Catherine Crescent, who currently rents apartment 15 on the second floor of 14 Rue des Boulangers. From the outside, the building looks much as it would have when Jeanne lived here. As we wait, the large wooden door that once allowed carts to enter the courtyard miraculously lifts to disgorge a car from the depths of an underground carpark. Catherine tells us that the building was completely refurbished just a few years ago, with extra floors added. She directs us to a small shiny lift in the carpeted foyer, where soundproof doors guard access to discreet private spaces. It is hushed and modern and devoid of its history.

The rooms are small but bright: a narrow sliver of sun slides its way across the floor in the late-afternoon light. It’s the only time of day the rooms get any direct sun, Catherine tells us. It’s a quiet street, though, and has a friendly neighbourhood feel to it, unlike the larger busier streets nearby. Apart from the nice Italian restaurant and the humorously English-themed Baker Street Pub, most of the houses are private – concealing apartments or offices. It used to be noisy in the past, Catherine has been told, when they made metal bedframes in the street below, probably in the nineteenth century. But no matter how hard we listen, the only sound that penetrates the double glazing is the distant rumble of the Metro as it passes deep underground.

Today, these streets are filled with ghosts. The past and the present overlay one another like translucent sheets of paper until I cannot be sure which one is real and which one is not. The streets echo with the names of the scientists and writers that Commerson worked with, admired, studied and was inspired by. I walk along Place de Jussieu, named after the family of botanists who supported and encouraged Commerson and who published his work. I pass the street named after Guy de la Brosse, who founded the Jardin des Plantes. And on to Rue Linné, for the Swedish botanist who gave himself a Latin binomial, Carolus Linneaus, just as he did for every other known species on earth. His path travels at an angle into Rue Geoffroy-Saint-Hilaire, who convivially separates the Swede from his arch rival on Rue Buffon. The streets are mapped with ancient antagonisms, grand aspirations, achievements and failures.

I wonder where Jacques Labillardière lived, the botanist who wrote one of the first monographs on Australian plants and who named over 400 new species. The savants clustered here, in the streets around the Jardin des Plantes, a centre for research and science and knowledge, its own history recorded in patched and crumbling walls, the patchwork of buildings, and assemblage of trees and animals. I walk past the Australian wallabies in the old menagerie, which might well be descendants of those brought back on the Baudin expedition. The black cedar that Bernard de Jussieu carried back from Lebanon, in his hat after the pot broke, still stands on the path to the oldest metal structure in Paris – the gazebo of the director, Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon – ‘the father of all thought in natural history’.

The eighteenth century was the golden age of natural history at the royal gardens, one of the oldest of all of Paris’s scientific establishments. Buffon dramatically enlarged the institution, across gardens, collections, scientists and menageries. The institution hosted three professorial chairs and three demonstrators, in each of botany, chemistry and anatomy. And it was here that Commerson sought to advance his career in botany.

By 1764, Commerson was already well connected, with an impressive reputation. He had completed field trips to the Pyrenees, Provence and the Alps. Voltaire had asked him to be his secretary. Linnaeus had asked him to collect Mediterranean fish. Commerson declined the first offer and completed the second, although he broke off plans to publish his work on ichthyology to move to Paris.

Most biographies merely note that Commerson took up a friend’s invitation, probably that of the influential astronomer Jérôme Lalande, to come to Paris. Lalande was said to have shared Commerson’s letters with the botanist Bernard de Jussieu, who supported Commerson’s move.

‘The sorrow he felt at the loss of his wife and the solicitations of his friends finally determined him, in 1764, to go to Paris,’ concluded one of Commerson’s early biographers.

The coincidence of the declaration of Jeanne’s pregnancy with their move was never mentioned.

Perhaps Jeanne taking the name of de Bonnefoi in Paris was part of a gradual transformation from peasant to servant with a hint of respectability. But the disguise did not protect them from gossip. Rumours seemed to have reached Father Beau, three hundred kilometres away. Father Beau’s letter to Commerson has not been found but Commerson’s impassioned reply fiercely objected to Beau’s ‘inquisition’ of his personal behaviour and his assumption of ‘a second marriage’. Instead he seems to suggest that his brother-in-law should take his share of the blame for events.

‘It took you a very ardent zeal, sir, to dare to twist this rope at the expense of your own remorse: for I may ask you,’ Commerson retorted. ‘Who would be the cause of it if I were today, as you please to believe, on a path that were not according to God?’

The implication of a second marriage can surely only refer to Jeanne and this accusation suggests to me that it was Father Beau himself who introduced them.

‘Although no-one has the right to question me in this respect,’ Commerson continued, ‘I can nevertheless answer your kind solicitude by assuring you that I have benefited from the changed situation . . . a truth that costs me as much to admit as no doubt it does for you to hear.’

Commerson, and his infant son, were the beneficiaries of his wife’s estate. Perhaps Father Beau was concerned that marriage to Jeanne would jeopardise Archambaud’s future? But, no matter how much Commerson needed Jeanne, he did not, or could not, marry a servant, no matter how beneficial she might be.

Commerson was not merely being coy, or disingenuous, in obscuring the nature of his relationship with Jeanne. Cohabiting outside of marriage might have risked Commerson’s prospects, and it certainly jeopardised Jeanne’s freedom. Unsanctioned relationships were common in eighteenth-century Paris, but they carried the constant threat of a lettre de cachet. Such ‘sealed letters’ were originally a way for the king to issue orders and imprison people (a grand cachet), but by the eighteenth century (under Louis XIV), form letters were used to lodge accusations or complaints about immorality (a petit cachet). These were usually lodged by family members, to bring a wayward son, daughter or wife under control. But sometimes even neighbours or acquaintances lodged complaints. The authorities could lock up the offending parties – most of whom were women – for their own welfare.

The historian Arlette Farge records an example of a couple who objected to their son-in-law raising their grandson with a married woman. As a result of their complaint, the woman, of no relation to the complainants, was imprisoned. Perhaps it was unlikely that Jeanne’s family would write a lettre de cachet, but Father Beau might have wished to protect the reputation of his brother-in-law, and the security of his nephew’s inheritance.

There is no suggestion that Commerson and his brother-in-law fell out, however bumpy their relationship might have been. Father Beau ultimately defended his brother-in-law’s legacy, and Commerson continued to write to him regularly and affectionately. He always pleaded for news of his son and signed his letters: ‘I kiss you and my son a thousand times.’

He seems the very model of a devoted father.

Jeanne’s child was due in the middle of December 1764. When the impoverished women of Paris wanted to conceal their pregnancies they gave birth at the Hôtel-Dieu hospital on the Île de la Cité, although whether it was the women who wanted to be concealed, or someone else who wanted to conceal them, is not entirely clear. They were quite literally ‘confined’ and not permitted to leave, nor even to have visitors. They slept four to a bed and were dressed in characteristic blue bedclothes so that they could be spotted if trying to escape.

Paris is no place to try to find a missing eighteenth-century child, either then or now. All the parish records were destroyed in fires at the time of the Commune in 1871. But Jeanne’s biographer Henriette Dussourd kept looking anyway and eventually, in the Paris archives, found a child called Jean-Pierre Barret. He was ‘put to the wet nurse Françoise Bernage, wife of Jean Debayé’ in January 1765. No parents’ names were recorded, not even that of the mother.

I walk in all directions from Rue des Boulangers, pacing the terrain Jeanne would have traversed by randomly following older narrow streets. To the west I wander by Saint-Etienne du Mont, the Pantheon and Sainte-Geneviève library, past the Sorbonne to the edge of the Luxembourg Gardens until eventually, skirting the gardens, I find myself in front of Saint-Sulpice.

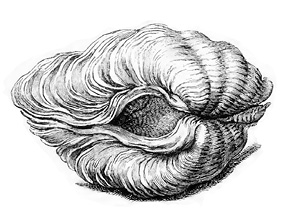

The holy water fonts at the entrance to Saint-Sulpice are famous for their elegant marble sculpted by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle and adorned with crabs, fish, corals and octopus. The fonts themselves are formed from two halves of a single giant clam shell. I wonder how they got here. Giant clams – Tridacna gigas – are so ubiquitous as holy water fonts in France that the species and the font even share a common name – bénitier. And yet these giant clams do not belong here. They are native only to the Pacific and Indian oceans.

The ones at Saint-Sulpice were a gift to Francis I (1494–1547) from the Republic of Venice, presumably originating from some East Indies trade. Giant bivalves have long embodied life-giving primordial waters with connotations of birth and feminine reproduction. Their original name, concha, means ‘vulva’. Think of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. Such fertile symbolism was quickly adapted to hold Christian holy water, and the vast size of the Pacific clams – some over a metre wide – added to their mythological qualities.

The fonts in Saint-Sulpice are a ghostly shadow of their living form, as pale and bleached as the bones in the crypt. Even Pigalle’s sculptures cannot revive them. There is no hint of life, of the dark quivering maw that cracks ajar like a fissure of night in coral rock. No soft velvet lips pulsing with fluorescent green and blue and yellow. No siphon drawing breath, no sudden snap, disappearing into invisibility. They are just another relic, martyred for a symbolism and a sacrifice they did not choose to make.

The fact that Jeanne’s child was named at all means that she must have had him baptised. Baptism in eighteenth-century France was synonymous with naming. The rare child who was not baptised faced a nameless life, being known only by a nickname.

In Morvan tradition it would be the father’s task to take the child to be baptised with the godparents, but whether he was the father or not, it seems unlikely that Commerson would have undertaken such a public activity. Her son’s baptism must have fallen to Jeanne.

The 5th arrondissement was packed with churches in the eighteenth century. I initially assume that Jeanne took her baby to the current parish church for Rue des Boulangers, Saint-Etienne du Mont. On a sunny day, the interior of Saint-Etienne du Mont is flooded with light from three rows of stained-glass windows. The pale stone interior is exquisitely carved into delicate sinusoidal curves, the paired pulpit staircases spiralling like the interior of a seashell, with coralline fretwork. It is architecture that inspires heavenward.

But the parish boundaries have shifted over time. In 1764, Jeanne’s parish church was actually Saint-Nicolas du Chardannet. It is a squat, heavy church with small high windows, an abundance of timber panelling, and an extreme brand of Catholic conservatism. A few elderly women wearing lace mantillas sit with bowed heads in the otherwise empty congregational seating.

Without the parish records there is no way of confirming if Jean-Pierre was baptised here. Perhaps instead, if he was born in the Hôtel-Dieu, he was baptised beneath the fading pastoral trompe l’oeil of the chapel in the foundling home next door. For it was there, at the Hôpital des Enfants-Trouvés, that Jean-Pierre was left.

The Foundling Home once stood on the forecourt of the Notre Dame Cathedral right next to the public hospital Hôtel-Dieu, which still occupies the site. The cobbled street it stood on still runs up to the door of the cathedral. Successive buildings on the Île de la Cité have been used to house the children. But the Foundling Home was always in competition with its grander neighbours, and the homes for children were progressively demolished and cleared to create a better view of the cathedral.

I had wanted to walk the street that ran past the Foundling Home, traces of it still visible in the pavement. But since the fire that engulfed the Cathedral of Notre Dame, it is impossible to get close. Barricades block off every street and bridge. The entire forecourt is closed. At best I catch glimpses down side streets, where the sour smell of old smoke rises from cold stones. The world wept as the 850-year-old cathedral burnt, windows illuminated by the inferno as the spire erupted like a chimney of flame into the night sky. It was an ironic inversion of the fires that burnt around Notre Dame in Victor Hugo’s novel that brought the cathedral such fame in the eighteenth century.

It is always sad to see something old and beautiful destroyed. We can never rebuild ‘the oak forest’ that made up the roof. One thousand three hundred mature oak trees, each 300–400 years old, equivalent to an old-growth forest covering twice the area of modern-day Paris, were harvested in the twelfth century to build this roof. There are not enough harvestable oaks this age left in all of Europe now. Likely neither the roof nor the forest can be recovered.

Biologists live with the grief of watching beautiful, unique and ancient things snuffed out of existence every day. Over the centuries the task of the biologist has shifted, from describing new and wondrous things, to hastily recording their all-too-sudden demise.

‘To see something so beautiful and so carefully constructed be damaged by forces out of your control is very painful,’ explained Jonathan Kolby, ‘As a scientist who studies species that are going extinct right now, this is the feeling I grapple with more often than I’d like. The irreplaceable work of art that I worship is nature, and to watch it senselessly crumble to the ground every day hurts my heart . . . we’re surrounded by burning cathedrals built across millennia and no one seems to care.’

On the day that Notre Dame burnt down, the last female Yangtze softshell turtle died with barely a murmur to note the extinction of yet another species. Countless species of molluscs vanish into extinction without anyone even noticing, before science has even had a chance to describe them. We weep for the ‘offspring of a nation’s effort . . . the heaps accumulated by centuries’ while the world burns around us. We are weeping for the wrong cathedral.

Over a third of all children born in Paris in 1770 were abandoned. Over 1600 children were left at the doors of the Foundling Hospital in central Paris in 1772 alone. Babies could be left in a revolving babybox, or tour d’abandon in the outer wall. It was a system intended to keep the child safe from the elements and the identity of the mother secret.

‘After pulling the rope to ring the bell and awakening the nun on guard, she runs away through the darkness with her tears and remorse,’ wrote André Delrieu in his 1831 account of the facility.

How could a mother voluntarily relinquish her child to such an uncertain fate? Commerson may not have wanted any scandal, but Jeanne could have lodged a legal complaint and insisted that he marry her, or support her and her son. The historian Arlette Farge has found many such cases in the judicial records of eighteenth-century Paris, and the Commissioner frequently sided with the women’s claims. Women may be hidden and silent in many official histories, but in judicial archives they defend themselves with vigour, anger and determination. They have their own opinions, beliefs and agency. I can see no reason why Jeanne would have been any different.

If Jeanne had agreed to put her son in the Foundling Home, perhaps it was because Commerson used a similar argument to the one found in the archives.

‘I have been advised by a close friend, who found himself in exactly the same predicament,’ wrote a young man to the mother of his newborn child, ‘to do what he did and put the child in an orphanage, making sure that he could be recognized so that he could have him back when he wanted, and in fact he took him out a year after he was married. And so, dear friend, this is what I advise you to do. We can have the child whenever we want and it won’t set people talking so much. Anyway, we won’t be the first ones. It goes on all the time nowadays’.

There was an element of truth in this young man’s claim – it was going on all the time. It was not just the poor who abandoned children they could not possibly feed. The scientist Jean-Baptiste le Rond d’Alembert was the illegitimate child of unmarried but wealthy parents who paid for his foster care. The philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau secretly relinquished all five infants born to his working-class lover Thérèse Levasseur between 1746 and 1752, rather duplicitous behaviour given Rousseau’s philosophy of family and childhood. In 1764, the year that Jeanne’s son was born, Rousseau was publicly exposed by Voltaire.

It is true too, that parents could, and did, reclaim their children. While many children were abandoned without identification, others had detailed notes attached, with names, addresses, tokens, buttons, coins, medals, carvings, cloth or ribbon so that they could be reunited with their parents. There is a poignant display of such tokens, from children who were never reclaimed, at the London Foundling Hospital: testimony to so many parents’ lost hopes.

I don’t know if Jeanne left a token or if Jean-Pierre Barret was her son. But this name suggests a label by which he could be identified. It is not only her own surname (as she spelt it), but also the names of her father and brother. This child’s name implies familial bonds of affection. The name ‘Jean-Pierre’ connects the mother to her son and the daughter to her father and brother. She was neither alienated from her own family, nor from her child. Perhaps she planned to return in more auspicious times to retrieve him.

Retrieving a child was not always successful though. Farge also recounts the story of a mother who asked for her twelve-month-old son to be brought back from the wet nurse to Paris. But the child died on the water cart he returned on. The distraught mother recognised him only from the linen of his layette. She had not seen him since the day he was born. Babies were such fragile little creatures, so prone to dying, in orphanages as much as in the care of their own mothers. More than half of the children left in the Foundling Home did not survive their first year.

If Jeanne had intended to retrieve her son, she never got the chance. In March 1765, within just a few months of being given to the foster nurse, Jean-Pierre Barret had died.

It is difficult to imagine Jeanne’s role in Commerson’s scientific work when all the names I know from the Jardin du Roi were men. I know a few wives and daughters who helped with their work, but mostly these women are silent, invisible and almost unknown to us. And yet, in truth, the women of eighteenth-century France were both vocal and conspicuous. We can see them in the plates of Diderot’s Encyclopédie: in the workshops, on the streets, in the kitchens, in the country, writing, printing, riding, labouring, sewing and making buttons. There could be no doubting the value of women in skilled trades after engineers had to take instruction in Roman hydraulics from peasant women in Pyrenees bath towns to build the 240-kilometre-long Canal Royal en Languedoc (now the Canal du Midi) in southern France.

Women were far from silent in the sciences, despite being denied education. The brilliant physicist Émilie du Châtelet was famous in Jeanne’s time, and her publications and translations inspired generations. Excluded from male-only intellectual gatherings, she had dressed as a man to gain entry. At the time Jeanne was in Paris, an impressively experimental book on putrefaction was published anonymously to critical acclaim, although few would have guessed that its author was Marie-Geneviève-Charlotte Thiroux d’Arconville.

Jeanne would certainly have known of, if not met, Nicole-Reine Lepaute, the daughter of a valet and self-taught mathematical genius who calculated the trajectory of Halley’s comet, the transit of Venus and a solar eclipse, and compiled star guides used by astronomers and navigators. Lepaute collaborated with Commerson’s good friend Lalande and Commerson counted Lepaute as one of his friends and advisers.

Nor were women absent from the Jardin du Roi which, unlike the universities, allowed women to attend classes alongside men. A commitment to public education meant the classes were free, open to all and in French (rather than Latin). Commerson must already have been training Jeanne to help him in his botanical work. She would surely have had cause to study, admire and learn from the impressive artwork and dissections of Françoise Basseporte, the garden’s royal botanical painter. Even the most senior figures like Michel Adanson and Linnaeus deferred to Basseporte’s expertise in distinguishing species. Jeanne might even have attended the anatomy lectures of Marie Marguerite Bihéron whose exquisitely lifelike wax models were an international sensation. Such study might have been a good distraction.

There were plenty of role models for Jeanne in these circles. From all walks of life, these daughters of nobility, farmers, apothecaries, servants and tradesmen were linked only by their talent and intellect, and their determination to pursue their interests and passions no matter what obstacles were put in their way.

In late 1766, Commerson was offered the position of Doctor-Botanist and Naturalist to the King on board an expedition around the world, commanded by Louis Antoine de Bougainville, an important post on the first truly scientific expedition of exploration. Bougainville’s voyage was the beginning of a program of state-sponsored scientific discovery which would yield an unparalleled haul of new knowledge.

‘It is one of those events which is an epoch in the political and literary world,’ said Commerson.

The science on Bougainville’s ship was, like all of the French expeditions that followed, generously funded. Commerson’s salary of 2000 livres (less than the expedition commander’s, but more than either of the captain’s of each ship) and an equipment budget of 12,000 livres signals the beginning of a great campaign of intellectual discovery – the birth of anthropological, geological and biological sciences in the southern hemisphere alongside the traditional naval disciplines of astronomy, celestial navigation and cartography. Through all the political upheavals to come, France maintained a national commitment to well-funded scientific voyages – through kingdoms, republics, empires and restorations.

Commerson’s instructions were to make observations and collections on the coasts and interiors, to keep precise records so that he could give an accurate account on his return. In order to do so, he was to be provided with ‘all the items and belongings that will be necessary for your observations’ with the assistance of Pierre-Isaac Poissonnier, medical consultant to the King, inventor of the ship’s desalination unit and an influential ally.

Commerson was thrilled. Even as he outlined his dilemma as to whether to go in a letter to his brother-in-law, it was clear that his mind was made up. Should he stay in this life of mediocrity to which he had happily resigned himself? Should he stay for the ties of his son and family? Or should he travel in the footsteps of Vespucci and Columbus, and take this singular opportunity to witness all manner of new and wondrous things?

His friends all urged him to go – Bernard de Jussieu and Poissonnier as well as Auguste Charles de Flahaut de la Billarderie. The man he called ‘mon intime’, Clériade Vachier, from medical school and now practising in Paris, supported his decision, as did Nicole-Reine Lepaute.

By January, Commerson had made up his mind. ‘They tell me when I come back the Order of St Michael will be mine, posts and pensions will become available. Every door will be opened to me,’ he said.

But Commerson would need someone to assist him with his collections. His health was not the best. Everyone knew his limitations. And even this was generously accommodated.

‘I have been given a valet, paid and fed by the King,’ he declared happily.

Who would be the best person to take? Where could he find a servant with the knowledge, skills and expertise to help him? And, more importantly, the extraordinary level of stoic endurance he would require?

The official plan was, it seems, for Jeanne to stay and look after the house. Just before he left Paris, on 14 December 1766, Commerson wrote a long and detailed will, mentioning Jeanne in the eighth clause.

‘I bequeath to Jeanne Barret, known as de Bonnefoi, my housekeeper, the sum of six hundred livres,’ he wrote, ‘paid in one amount and this without prejudice to the wages I owe her from the sixth of September 1764 at the rate of one hundred livres a year, stating furthermore, that all the bed and table linen, all the women’s dresses and clothes I may have in my apartment are her personal property, as well as all the other furniture, such as beds, chairs, armchairs, tables, chests of drawers, excepting only the above-mentioned herbaria and books and my personal effects left to my brother as stated above. I wish that the said furniture shall be handed over to her without hindrance after my death, even if she retains for one year following the present one the apartment I will be occupying at the time, even if this were only to give time to sort out the collections of natural history that are to be sent to the Royal Cabinet.’

This document is the only time that Commerson admitted that he knew Jeanne before the voyage and that she had worked for him in Paris. It is a telling revelation. If he had truly wanted to keep her presence a secret, he could have entrusted the matter of reimbursement to his dear friend Vachier. But Commerson does not leave Jeanne’s entitlements to chance. Even at the risk of exposure, he puts her interests first.