6

fitting out for the voyage

Rochefort, 1767

It is hard to imagine the forest of sailing ships that once crowded the seaports of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. It is hard enough to even imagine what working eighteenth-century ships might look like, let alone how they sailed and how those who sailed on them lived and worked.

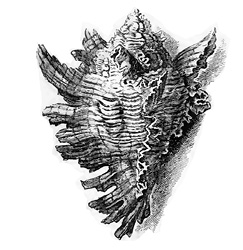

The world of these old ships has completely vanished. Long-dead forest timbers were never intended for a life at sea. They mouldered with rot and damp, were tunnelled by teredo worms, chewed and gnawed by anything with teeth, beak, shell or drill. They buckled, twisted and splintered under the constant strain of wind and water against warp and weft. Few timber sailing ships have survived from before iron frames gave their spans rigidity.

Only two ships remain afloat from the mid-1700s: the English Victory, saved by its fame as Nelson’s deathbed; and the salvaged shipwreck of the American gunboat Philadelphia. The oldest ship still found regularly sailing offshore is the iron-hulled windjammer the Star of India, built almost a century later in 1863.

In every harbour I visit, I look for traditional boats, trying to recapture something of that lost world depicted in vast detail in Claude-Joseph Vernet’s paintings of French ports. The port of Saint-Malo seems a promising place to look, during a lunch break from a writing festival several years ago. A light drizzle keeps tourists at bay but the harbour itself is crowded with vessels of all shapes and sizes. Large ships loom in distant mist, grey and streaked with rust, overhung by industrial-scale cranes. The fishing fleet bristles with aerials and receivers, sonars and radars, back decks awash with machinery for hauling monster nets and pots. Closer by, a motley collection of recreational vessels fills every available space: small and large, sailing yachts and motor cruisers. Most gleam white and silver with glass fibre and aluminium, ferro-cement and steel. Clean, sharp, modern and uniform.

But my eye is always drawn to the irregularities of timber and rope, the dark spars held aloft with deadeyes and lanyards, the smoothed anomalies of timber planking. The ‘trad-riggers’ are not hard to spot: dark among light, complexity among simplicity, vertical among horizontal, heft among the insubstantial. They stand out, like old-growth trees in a plantation, against a monocultured forest of silver ‘radio masts’ that give modern sailing boats their Marconi rig nickname. Once this forest would have been a veritable ecosystem of ocean-going, coastal and riverine vessels, all grown from oak, hemp and cotton, all built for war, trade and survival, and all curved into exquisite shapes by the pressures of the water and wind that powered them.

As it happens, the Étoile du Roy is in Saint-Malo port and open to visitors. This vessel is a replica sixth-rate frigate, built in Turkey in 1996 to star as the Indefatigable in the TV series Hornblower, then as Nelson’s Victory in the Trafalgar commemorations before transferring to a French flag in 2010. The Étoile du Roy is a little larger than the Boudeuse and larger again, though not as roomy, than the Étoile. An expert eye could see it is not a French-built ship, with less ornate head rails that terminate further forward. The enthusiast would complain that modern construction constraints have compromised sailing ability, but the reconstruction is as close as I can get to the ship Jeanne sailed on.

I have the Étoile du Roy to myself when I visit. The bright yellow and blue paintwork gleams against the black hull and the rain slicks the decking timbers shiny and treacherous.

‘One hand for the ship, one hand for yourself.’

I run my hand down the timber handrail, remembering the ease with which I once swung myself around the confines of a boat, the monkey-like flexibility of childhood in an environment that required agility, balance, strength and constant vigilance. I duck my head, grip tight to the handrails and step, slowly and very carefully, into the dark.

Only the upper decks are open to the public. I suppose most visitors don’t find the holds and storerooms and bilges very interesting. I like seeing the bones of the ship, the ribs and knees that give it shape, the long keel that holds the ship together, the ballast that weights its stability. The lower decks expose the ship’s shape and condition – the split seams, the hogged keel, the cracked ribs. The patches and repairs reveal the constant struggle against weather, worms and waves. I resist the urge to dig my thumbnail into soft timbers to check for rot, the maritime version of kicking the tyres – a legacy of a childhood spent in too many boatyards.

Peering down a companionway leading to the lower decks, I glimpse an engine room. There are limits to authenticity on any ship. I will never find a ship with the original bilge pumps in working order, or an operational original woodstove in the galley, nor a revolutionary cucurbit, designed by Poissonnier, to extract fresh water from salt. No-one wants their ship to sink or burn to the ground. No modern ship will have a crew of over 200 men, living, breathing, sleeping, belching and farting in close quarters. No fetid water in swollen casks, no weevilled biscuits or salt-encrusted meat, no lack of fresh vegetables. No livestock loaded in crates on the deck: goats, cattle, horses and chickens. No scurvy, no fever, no wasting diseases. No-one wants their crew half dead either.

I try to fill each empty space with people and equipment. Mentally, I stack all the spaces with stores and livestock. I fill the decks with small boats and cages, temporary cabins for the galleys. I remind myself to triple the size of the mooring lines that coiled, in those days, like giant boa constrictors. I take photos, too dark to see properly, too cropped to capture the shape or size of the spaces, knowing that later I will want to see the thing that is just out of view. I try to remind myself that the past is not just ‘us in funny clothes’, but the effort required to sustain the reconstruction is too hard. I can barely even see this ship as it would have been, let alone 100 ships packed into a busy port crowded with people shouting, ordering, working, loading, carting, cleaning, building and repairing.

So how am I to find a single young woman, some 250 years ago, dressed as a man, with her head down to avoid attention, on her way to join a ship that was to sail around the world? Much less find her place in a world where women were not wanted?

Commerson left Paris directly from Poissonnier’s house but I think he travelled alone. He does not mention a servant or a travelling companion in a letter he wrote to his brother-in-law. He uses the singular pronoun in his letter, not a plural.

He took just three days to arrive in Rochefort from Paris, a cracking pace for a horse-drawn diligence in the middle of a freezing winter. We know exactly what route he took, the conversations he had, and about the accident in Niort where he was nearly crushed by a carriage because of ‘the clumsiness of a half-drunk postilion’, reopening an old wound that would plague him for the rest of his years. But we don’t know where Jeanne was.

To all intents and purposes, she was still in Paris, looking after the house. This was the story Commerson told in his will. Likely this was the story they told everyone else. But Jeanne de Bonnefoi, the housekeeper, disappeared from Paris without a trace.

In her place, a quietly confident young man, Jean Barret, former valet to a Genevan gentleman, appeared in Rochefort, looking for a new position.

It was not a good thing for a woman to dress like a man. Moses was quite adamant about the matter:

‘A woman shall not wear a man’s clothes, and a man will not put on a woman’s garment: anyone who does this is an abomination to God.’

Eventually the priests realised that perhaps there might be circumstances where a woman could dress as a man without sin. It was better to wear men’s clothing than none at all, obviously. By the time of the ancien régime in France, the avoidance of death or rape was deemed a sufficient excuse for committing the mortal sin of wearing ‘the wrong trousers’. But otherwise, such ‘cross-dressing’ remained a crime.

Women were arrested for being ‘disguised’ as men. A chambermaid, Suzanne Goujon, was sent to prison for dressing as a man and renting lodgings ‘with no female clothing in her possession’ in 1749. So was Marguerite Goffier, who went to the cabaret dressed as a man. But still they persisted. Françoise Fidèle dressed as a man to enlist in the Paris militia. She indignantly declared that ‘she was a good girl and had done nothing to offend her honour and that she was not the first in her family to disguise herself in order to enter the service’.

It was not just French women, either. English women too, like Hannah Snell, Mary Lacy and Mary Anne Talbot, signed up and served as men in the British navy in the late eighteenth century and later became quite famous for their exploits. Or ‘William Brown’, the African-American woman who served as no less than captain of the foretop on the Queen Charlotte for eleven years, continuing even after her gender was revealed. Maybe women were not supposed to be on ships, but they were not uncommon either.

Successfully passing as a man takes more than just clothes. It is also about behaviour and attitude. Men are louder and they talk more at work. They fart, belch, sneeze and piss louder than women. They take up more space: they sprawl, stride, stretch and sit with legs spread, feet apart, arms open, chest exposed in challenge. To sit like a woman, legs to one side, coiled, crossed and covered, is to adopt a defensive posture. In order to blend in, Jeanne had to ‘stand out’ like a man.

The English women frequently mentioned having to stand up to men, shout them down and show no fear. Mary Lacy had no choice but to fight one young man who challenged her. She was not as strong as him, so she decided that she would just have to outlast him. No matter how often he knocked her down, she kept getting up and would not give in. Eventually he tired and conceded defeat, becoming her friend and ally.

Youth and class were on Jeanne’s side. Not all young men on the ship had fully developed the masculine traits that mature and fill out in older men. Furthermore, a valet to a Genevan or Parisian gentleman might naturally be expected to be a little more effete in his mannerisms than a rustic sailor. She was unlikely to be challenged to fisticuffs, but she carried two pistols in her belt even so. She was prepared to defend herself.

I imagine that when she presented herself to apply for the position as Commerson’s servant in Rochefort, Jeanne appeared as a quiet and serious young man, already dedicated to, and knowledgeable about, botany and science. Altogether a suitable boy.

On her arrival in Rochefort, Jeanne would have smelt the salt and seaweed tang of the coast – her first taste of the sea. Rochefort was a beautiful city, which offered ‘an infinity of things for an observer to see’. It was as white and clean and uniform as Paris was dark and twisted and crooked. There was no mistaking it for anything but a naval town. A partial star fort on a long loop of the Charente River, the naval shipbuilding complex was impenetrable from the sea, unassailable from land and protected from all weather. Parisian critics complained about the surrounding swamp, the mud and the unhealthy airs, but a little bit of water never bothered a sailor. Everything had a parade-ground neatness to it. The buildings were long and straight, with regular windows along their lengths. The roads turned sharp left or sharp right with military precision. Nothing stepped out of place.

After a century of neglect, modern Rochefort has been returned to its former glory, its historic buildings restored, renovated, cleaned and rebuilt, revealing their sharp pristine lines and crisp paintwork. Christèle and I drive through the busy streets towards the port in the centre of town. Christèle has not been here since seaside holidays as a child. She does not remember it being a very exciting place.

Our accommodation is moored at Quai aux Vivres – the dock where the Étoile would have loaded rations from the warehouses, which are now being renovated into apartments. We are staying on board a beautiful little Dutch sailing barge built in 1896. As I clamber down the companionway into the main cabin all neatly fitted out with carved wooden fittings and homely creature comforts, I feel as if I have stepped into a manifestation of my childhood dreams. And even though we never leave the dock, the gentle rock of the boat beneath my feet, the cheerful camaraderie of neighbouring boaties, the slap of rigging in the night and the intricacies of marine stoves, toilets and showers bring back childhood memories and make me long to cast off the mooring lines, hoist the sails and slide off down the Charente River towards the sea.

The Étoile was expected to be ready by December but the authorities at Rochefort did not consider her mission to be a priority. Bougainville would have to wait in South America for his consort ship. It would be February before the Étoile departed.

‘The Rochefort Intendant, Mr de Ruis-Embito, has placed in the way of outfitting every difficulty and obstacle he could, and an intendant can do a great deal of harm when he puts his mind to it,’ Bougainville noted in his journal.

The Étoile was not a new ship. Originally built as a trading vessel, Paulmière, in 1759, it was purchased by the navy in 1762 and renamed the Étoile. About two-thirds the size of the larger frigate, the ship was much roomier and required far fewer men than the Boudeuse to sail. There were only 120 aboard, giving everyone a bit more space – when it was not loaded to the gunwales with supplies and goods.

Such fluyts were modelled on a Dutch cargo vessel and known as ‘corvettes of burden’. They were specialist transoceanic voyagers, with no adaptation to military service. The Dutch invested in trade, not war. The flutes were cheap to build, required fewer crew and could carry twice as much as other similar-sized ships. They played a significant role in Dutch supremacy over long-distance trade routes. Traditional flutes have flat bottoms and near vertical sides, as square as the limitations of steamed ribs and planks will allow. But the Étoile’s mid-section revealed a gracefully sloping hull beneath the waterline, designed to improve sailing performance as the ship heeled. The ship might have been beast of burden, but it still displayed the innovative flair of French maritime engineering.

Rochefort was a sophisticated production line for ship preparation. At the far end of the riverbank were the shipbuilding yards themselves, where bones of oak rose in various stages of keel, frame, ribs, planking and sheathing from within the stone crucibles stepped into the river bank. Six thousand trees, each 300–400 years old, per ship.

Vats of ‘Norway tar’ anointed acres of rope and filled the air with its smoky aroma. The forges glowed red with constant fury, producing ironwork. The flat horizon of the riverlands stretched around them, punctuated by bristling masts in all stages of dress. The great spars were lifted diagonally alongside the mast-raising pontoons, their standing rigging draping limp from the crosstrees. Once they were upright, tiny figures scurried spider-like along them, weaving their web of rigging – ratlines, halyards, clew lines, braces, reefs, lifts and tackles – until the ships were fully attired. Each quay along the river offered a different service for the new ships – like a specialty street of tailors where one might buy shoes, trousers, coats, scarves, hats and pipes at different shops. Here the ships progressed though masting, rigging, ropes, sails and stores until they could sail out to sea, in full regal dress, like a flotilla of dignified matrons across a ballroom floor.

It was the Royal Corderie that dominated the complex – then as it does now – a long low white building with elegant classical repetition. Its foundations ‘float’ on an oak raft on the unstable ground – an engineering masterpiece. The long narrow halls allowed the production of reams of hemp and linen rope. There are more lineal metres of rope on a ship than timber. The Corderie was as vital for naval success as the oak forests or the blacksmith’s forges.

Some ropes were as thick as a man’s arm and heavy, even when not laden with water. Jeanne would have recognised the equipment used to coil and twist them as a gargantuan version of a peasant woman’s spinning wheel. Giant metal combs scraped and straightened the hemp fibres. The fibres were separated, then spun onto cotton reels the size of a loaf of bread. These reels of thread, some 30 or 40 of them, were mounted on a shelf of spindles and all spun together into a single cord. It was an impressively complex process. The straightening and smoothing work that Jeanne would have done with delicate precision between the thumb and finger when spinning, must here take six or seven fully grown men all their strength as they hauled on recalcitrant lines that bucked and twisted their objection to being harnessed into servitude.

Even modern ropes are wild and dangerous creatures, twisting against their inborn tensions and whipping with sudden viciousness. Ever since I can remember I have been warned about the perils of ropes entangling the unwary and dragging them overboard or crushing them in a deadly embrace. Never wrap a rope around your hand for better grip, my father warned me. Better to lose the load than lose your hand.

When we finally departed from Port Adelaide on the first stage of our travels around Australia, my grandfather travelled with us. We spent a rolling night sheltering behind Kangaroo Island, before continuing to the tiny safe harbour of Robe and then to Portland, across the Victorian border. We struggled to manoeuvre alongside the wharf in the busy harbour under the critical gaze of watching fishermen. Dad threw the boat into reverse to try a new approach and I watched in horror as a stray mooring line snaked up my grandfather’s arm and pinned him helpless against a bollard. I could see the heavy nylon rope biting into his soft brown skin as I shouted in panic. Fortunately the boat had little momentum and he was quickly freed with no more than some nasty bruising. The incident certainly confirmed my grandmother’s belief that boats were far too dangerous to live on.

I often think about ropes when I’m writing: the threading of multiple narrative strands through a single work with differing perspectives. How to spin such epic tales that stretch across voyages and lifespans, fraught with the challenges of maintaining a continuous unbroken ply of fibres without loose ends or frayed threads? I hate frayed ends. I have always derived great satisfaction from sealing the ends of nylon ropes over the stove and pressing the wax-like plastic into a rag until it cools as a smooth neat lump. Hemp ropes had to be traditionally whipped with tarred flax twine wound neatly around and around for several inches before being sealed off and securely fastened. Such binding was unbreakable. The fishermen in Port Lincoln often laughed about Caliph’s rigging ‘held together with bits of string’. Their sneers seemed justified one day when, lifting a heavy load on board, a shackle in the rigging snapped. But the rope whipping was unbroken – it was a welded metal bracket that had snapped under the strain.

I wish I had learnt to splice ropes with a flashing marlinspike, seamlessly weaving and knitting the strands back against each other. Writers often use the metaphors of braiding and spinning to describe their work, but I am starting to feel that writing this book is more like ropemaking: a test of strength that threatens to overwhelm me in a tangle of serpentine twists. The customary skill of a practised hand may not be enough for this fibre, so much as the brute force of will, pitting the twists of each strand against one another to create a durable and seamless cable that folds in reluctant coils at your feet.

So many feminine crafts are amplified and made masculine on ships. The delicate work of the seamstress takes on gigantic proportions. On the banks of the Charente in Rochefort, acres of golden hemp were cut and layered, hemmed and stitched, edged and finished. My mother sewed Caliph’s brown cotton duck sails on an old Singer sewing machine in the hall of the local high school where she worked. Layer upon layer of fabric stitched together to make the wide sheets. Endless miles of stitching with giant needles pushed through stubborn cloth with a thickened leather sailmaker’s palm. Brass eyelets were pounded into gleaming rows across the width to take the reef-lines used to shorten the sails in high winds. Heels and heads were reinforced with six, eight or ten layers of cloth, every edge corded with rope to take the full weight of gale-force winds.

At last, finally, when the ship was equipped with all the necessities, it was time to load such supplies as met human needs. Novelist and botanist Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, heading for Mauritius a year or two later, provided a vivid account of the loading and departure of such a ship.

‘I have given you a general sketch of the disposition of our ship,’ he wrote, ‘but to describe the disorder of it, is impossible. There is no getting along for the casks of champagne, wine, trunks, chests and boxes everywhere about. Sailors swearing, cattle lowing, birds and poultry screaming upon the Poop; and, as it blows hard, we have the additional noise of the whistling of the Ropes, and the cracking of the timbers and rigging as the ship rolls about at anchor. Several other ships lay near us, and we are deafened by the hallowing of their officers to us, through their speaking-trumpets.’

The Étoile was no different. And into this chaos, stepped Jeanne.

It is a bit of a mystery what Jeanne looked like – either as a man or as a woman. She was small and strong, a little on the plump side, and apparently not particularly striking in any other way people thought worth mentioning. I wish there was an illustration of her standing on the deck, a quick portrait by one of the crew – like those done by Charles Alexandre Lesueur on Baudin’s voyage or Louis Le Breton on Dumont d’Urville’s. Many of the later voyages employed talented artists to document the voyage and its collections, but not this one. Commerson would have to do his own drawings at sea.

There are no known images of Jeanne drawn from life. A picture of her was created in 1816 by Giuseppe dall’Acqua for an Italian account of James Cook’s voyages. In this full-length engraving, she carries a bundle of plant material limp over one arm, a motif for her occupation. Her plain face gives nothing away, discreetly looking down and away from the viewer. She does not look particularly short or plump, nor curvaceous or freckled. There is no sense of individuality in the picture. It’s just a placeholder, a symbolic representation of a character created well after her death by an artist who never met her.

Dall’Acqua dresses her in loose sailor’s clothing, characteristic of the times – shapeless and androgynous. A red woollen cap covers curly hair, a short navy blue peacoat opens to reveal a pyjama-like striped shirt and long wide-bottomed pants divided by a broad sash around her waist. She wears white stockings and black court shoes, the kind that I know were issued to the crew of Kerguelen’s exploration voyage a few years later. The image is in the same style as many other dall’Acqua ethnographic engravings representing people in their ‘native ethnic dress’ for the travel books he illustrated. These are not portraits of individuals, they are ‘types’ symbolising a race or a culture. Or, in Jeanne’s case, an anomaly.

I’m not an expert in French naval clothes, but I don’t think there were regulation uniforms for French sailors before the Revolution. Red caps usually signify convict labour. I search through the series of hugely detailed paintings of French ports by Claude-Joseph Vernet painted in the mid-eighteenth century. For the most part, the workers and sailors in the port wear knee- or full-length pants, shirts and jackets in varying shades of white and blue.

And in any case, Jeanne was not a sailor and she was never part of the crew. She was a gentleman’s valet or a manservant. Valets wore neatly tailored stockings and breeches, shirts, waistcoats and fitted jackets, in a simpler, less grand version of their masters, perhaps even their master’s old clothes. Her origins might have been the lowest stratum of a society but, as a servant, she had attached herself to a higher level, and would almost certainly have dressed according to her new-found status, well above the sailors. The clothes make the man, as they say, or, as the French say, the habit makes the monk. I don’t believe that Jeanne ever dressed like a sailor.

When Rose de Freycinet stole aboard her husband’s ship as it left for a voyage around the world in 1817, she cut off her hair, dressed in men’s clothing and boarded at night, grateful for the clouds. She was afraid of being recognised, despite her disguise.

‘Before leaving the port we had to stop at the exit to give the password and somebody brought a light and I did not know where to hide myself,’ she wrote. Someone asked her who she was and a friend quickly answered that she was his son. ‘I was extremely agitated all night, thinking all the time that perhaps I had been recognised and that the Admiral-commandant, having been informed, had sent orders to put me ashore. The least noise frightened me and I was afraid until we were outside the harbour.’

Both Rose, and her husband, had much to risk by discovery. But once safely at sea, she had the security of her husband’s protection and the privacy of the captain’s cabin. When they were far enough away to avoid the navy’s wrath, she opened her considerable trunks and returned, with obvious pleasure, to women’s fashions.

Jeanne’s path onto the ship was less troubled. Once she had convinced herself, and others, that she could pass for a young man, there was no reason for her to sneak aboard in the dead of night. She boarded as a legitimate member of the ship’s company, and no doubt with much work to do getting all of Commerson’s equipment and supplies successfully and suitably stowed on the increasingly crowded vessel.

Once Jeanne and Commerson were on board, they were allocated sleeping quarters. Commerson was given ‘the most beautiful and most convenient of the vessel, without taking into account that of the captain himself’. This was not to say, however, that the accommodation was luxurious. The cabin had barely the dimensions of a household closet, with hardly headroom to stand, and was shared with other officers. It seems likely that this space would also have been shared with the officers’ servants and Jeanne.

It must have been strange to embark on a ship of 120 strangers, none of whom you had met before, and none of whom you would be able to escape. Jeanne would be stuck with them for over a year, in a very small space, under difficult and testing conditions. It was not so much the sailors, the matelots, that Jeanne needed to be worried about. The crew of the Étoile were, like their officers, mostly rough-tongued, hardworking Bretons, who had their own distinctive and conservative perspective on the world. They had a well-established ecosystem in the focsle, from solid, unwavering helmsmen to the fearless, agile topmen. Sorted into watches, they followed the lead of their boatswains and leading seamen, accepted their orders and their punishments. The carpenters, caulkers and sailmakers protected their shipmates with wood, oakum and thread, the gunners with cannon and the fusiliers with rifles. Each tribe kept to itself and everyone knew their place.

But the stern quarters of the ship were a very different matter. The officers and passengers were a potent mix of pre-revolutionary France, with all the aspirational social tensions and conflicts between merchants and nobles, city and country, sailors and civilians, untutored and educated, tribe against tribe. Everyone had their status, their position in the hierarchy, and there was a constant battle to either maintain or improve it. Nobles thought they outranked civilians, gentlemen thought they knew better than experienced sailors. Surgeons bristled against naturalists who were, after all, just glorified medical graduates.

The surgeon on the Étoile was François Vivez. Vivez had been sailing since the age of seven, with his father who was senior surgeon on the Formidable. He knew far more about sailing ships, their crews and their ailments than a hopeless landlubber like Commerson. But Commerson was a highly regarded medical practitioner, had been appointed as the King’s Naturalist and was paid more than Étoile’s Breton captain. I suspect this relegation did not please Vivez.

Others passengers and volunteers also occupied ambiguous places in the naval hierarchy. Some of them were important, depending on their standing or temperament or relationships. Pierre Duclos-Guyot was the younger son of the captain of the Boudeuse and sailed with his brother Alexandre to South America before transferring to the Étoile for the remainder of the voyage. Then there were the butchers and bakers, the musicians and the ship’s boys – dozens of these, mostly stowaways and deserters. The captains of these ships, unlike ships of state, were obliged to feed and shelter all those on board until they could be put ashore.

And finally, there were the servants. Each of the officers had a servant, as did Commerson. Bougainville had four. Not many people write about the role of servants, on land or at sea. In the English navy, the captain’s servants were not so much staff as sinecures allowing him to provide for old friends and family.

‘A captain in the old time frequently put to sea with a little band of parasites about him,’ wrote John Masefield in his depiction of sea life in Nelson’s time. ‘They stuck to him as jackals stick to the provident lion, following him from ship to ship, living on his bounty, and thriving on his recommendations.’

Ship’s boys as young as thirteen often acted as officers’ servants, although they were effectively training to be either sailors or officers, depending on their social background. Such servants played complicated roles as trainees as well as domestic staff, moving between the professional and domestic, crossing social boundaries between classes, as well as between the lower deck, the wardroom and the captain’s cabin. Whether they were the sons of aristocrats or homeless stowaways, they were privy to many secrets of the ship. The role of a servant – amorphous and variable – was the perfect foil for someone in disguise like Jeanne.

The Étoile’s muster roll has never been found so we don’t know how many servants were on the ship, or who Jeanne’s peers were. They may have been subservient and polite, but they occupied the positions of privilege and knowledge attached to their masters, for better or worse. They were bound by naval regulation, but, like personal servants within households, also sat slightly outside the usual hierarchy.

As a servant, Jeanne’s role would have been a mix of domestic and professional work. She would certainly have been required to carry out all of Commerson’s domestic labour: washing and repairing his clothes, making his bed, fetching candles, keeping his cabin tidy, ensuring that he received his meals. These were generic tasks required of any servant, but they were also specific to Jeanne. Vivez described her washing clothes, and noted that she was good at sewing and had dexterous hands. Keeping Commerson fed and his goods tidy was no easy feat, given his preoccupation with natural history and neglect of his own wellbeing. Jeanne, unlike some of the other servants, was not training for a naval career, but in effect for that of a naturalist, or a naturalist’s assistant. Her work would probably have been more onerous than that of most servants.

Just before the ship was about to leave, Commerson added a casual postscript on a letter to his brother-in-law.

‘I must warn you in advance,’ he wrote, ‘not to believe any of the rumours that might spread after my departure. There is nothing so common in seaports as spreading false stories about the ships that have left.’

Perhaps he meant stories of ships sinking, being overrun by pirates or mutinous crews. Or perhaps there were other shipboard rumours that Commerson did not want his brother-in-law to hear.