7

all at sea

The Atlantic, March–April 1767

There is nothing quite like the sensation of wind filling the sails: that sudden lift and sweep of the hull beneath you as if an inert floating object had unexpectedly come to life, risen from its slumber and set out on a journey of its own determination. All the random creaks and groans, the anxious tossing at anchor like an unhappily tethered mare, the loose slap of rope and canvas: all this uneasiness ceases as every fibre, every compass needle swings onto a single setting, and all the wild energy of wind and wave is harnessed into a swift and silent forward thrust.

It was a beautiful morning – fine and clear – when the Étoile finally sailed off anchor under the topsails and mizzen. In the light airs they were soon under full rig, raising as much canvas aloft as they could to drive the heavily laden vessel through the water.

The ship was chock-a-block with goods to trade – on the bridge, in the steerage, on the quarterdeck, in the large cabin – causing landlubbers like Jeanne, unaccustomed to the confines and athletics of marine life, to stumble, trip and curse as they accommodated themselves to their unstable home. But they soon found their feet, buzzing with excitement and praising themselves for their sturdy stomachs as the Étoile sailed north-east across the sheltered Bay of Biscay and believing themselves well attuned to the rigours of the ocean life ahead of them.

‘I am already no longer a land-dweller,’ Commerson wrote as they left the placid waters of the Charente River. ‘I am writing this from the harbour off the island of Aix. My little test at sea was not painful: I think I shall enjoy a marine existence. I have not yet felt nauseous.’

His misplaced confidence is amusing. It is one thing to wear the right clothes, to talk the right talk, to step onto the deck of a boat, adjust yourself to its balance and confines and feel that that you are ready for a life at sea. When I was growing up, the stories of such new sailors were legendary. People set out on their sailing adventure of a lifetime, heading into open ocean, setting their autopilot, putting on their pyjamas and going to bed while their boat steadily sailed itself into the rocks. There is world of difference between looking the part and living the part. Commerson’s seaworthiness was yet to be tested, and so too was Jeanne’s manliness.

The open sea soon proved a different beast from the protected waters of the river mouth. The seasoned sailors watched as the ship began to roll under the first lift of swell. The gentle motion started like a rocking cradle, then increased in violence, with feints left and right as if intending to catch the unwary by surprise. As the ship pitched and swayed with all the fitful temper of a drunken sailor, the passengers surged to the gunwales, heaving in sympathy. Jeanne, like all the other greenhorns, was forced to empty her stomach of the customary tribute to the ocean gods, but still the deities demanded more. The unfortunate novitiates retched compulsively over the side with hollow cries, until their eyes blurred and their limbs collapsed from the convulsions.

‘Eat, eat,’ exhorted Commerson, between his own violent paroxysms. ‘The convulsive efforts of an empty stomach will soon vomit blood and some pulmonary vessels could well break.’

But no food or drink tempted his own appetite, not even brandy. By the end of the second week, Jeanne had recovered and Commerson was the only passenger still ill, still vomiting blood. He began to doubt the wisdom of them having embarked on this voyage. Perhaps the ship was a trap. Someone had set the tasty morsel of bacon to entice them on board, he moaned, but once the sails were raised, the trap snapped shut – there was no way they could leave and there was nothing to do but chew on the bars.

Jeanne would have had no time for such regrets. She had to keep her master fed and clean up what he could not keep down: washing, mending, cleaning, feeding, tending. The wound on Commerson’s leg had now reinflamed, oozing pus and ulcerating. It needed regular cleaning and dressing.

It wasn’t until March that Jeanne would have been able to go on deck more often with Commerson. They watched a sleeping turtle drifting past, heavy as a barrel full of water and covered in barnacles and small shells. They saw porpoises, but few fish, although the men said the waters usually seethed with bream. But soon enough, a couple of sharks were hauled aboard, which needed to be dissected, analysed and described.

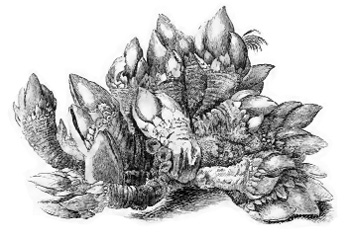

It was an old sea myth, Commerson insisted, that these sharks were always accompanied by pilot fish. What possible value could such an inconsequential fish have to a large and impressive predator? And yet here they were, small black and white consorts that ‘liquidly glide on his ghastly flank’, sometimes four or five to a shark. Commerson accepted the proof but remained mystified. The pilot fish might benefit from the shark’s protection and morsels that fell from its mouth, but what did the shark gain?

There was no doubting the loyalty of the pilot fish. They hung close to their large companion, rarely darting far away. Even when a shark was hooked and hauled aboard, the pilot fish followed it up, only falling away as it swung in the air. They rushed back and forth, greatly disturbed by their loss, and trailed in the ship’s wake for days as if hopeful of their companion’s return.

Jeanne might have had a clearer insight into this unusual relationship than Commerson. Those who have always had others tend to their menial domestic tasks are often oblivious to the value of such labour – until it disappears. The sharks open their mouths in passive acquiescence and allow the pilots to clean between their teeth. Without their loyal cleaners, the sharks would soon be laden with parasites, drained of energy and vigour.

The benefit of such relationships is always mutual.

The story of the expedition, and Jeanne’s role in it, was told by a variety of participants. There are different accounts written by different crew members for different purposes. Some are purely functional – carefully dated daily accounts of the weather, the ship’s course and major events. Others are personal and anecdotal, written long after the events. Many of them were intended, ultimately, for publication. Exotic travel narratives were popular in the eighteenth century.

A journal was a useful activity to while away the hours of a long sea journey. Many of the journals were rewritten several times, so multiple versions exist, telling of varying events. Their writers collaborated and consulted with each other. Phrases recur and repeat in different journals until it is unclear who said what and when. On many French naval journeys, the commanding officer collected (or confiscated) all the journals on a ship as official records, using them as sources for a combined ‘official account’ published with considerable state support. Some wrote their journals as letters, to avoid collection for the naval archives. Naturalists also published their scientific accounts, sometimes on their own, but mostly as ‘atlases’ appended to the official narratives.

Bougainville’s highly readable and popular account of the voyage was published soon after his return. It rapidly went into new editions, was abridged and translated, excerpted and quoted. More recently, Bougainville’s personal daily journal has also been transcribed, translated and published in English. Other journals have been retrieved from the archives and published in part or in extracts, sometimes in English. From the voyage of the Boudeuse we also have the journal of Nassau-Siegen (in three different versions); the account of the ship’s écrivain or clerk, Louis-Antoine Starot de Saint-Germain; and that of the volunteer Charles-Félix-Pierre Fesche – whose journal was possibly written in collaboration with Saint-Germain and also includes annotations by Commerson. On the Étoile, the young Pierre Duclos-Guyot kept a journal, often in concert with Commerson. Commerson wrote various manuscripts and journals as well as many letters, as did the surgeon Vivez (revised over time). The Étoile’s second-in-command Caro kept a fairly cursory sailor’s journal – probably one of the few not pitched at publication, but sadly, the captain’s journal by La Giraudais, which might provide a more objective account of some of the more contentious events on the journey, has never been found.

Jeanne warrants a page or two in the narratives of Bougainville and Vivez, is mentioned fleetingly in the journals of Saint-Germain and Commerson/Duclos-Guyot, disappears from successive versions of Nassau-Siegen’s account, and is entirely absent from the rest. It’s not a lot to go on. The record is both noisy and patchy. It’s like trying to follow a conversation at a party where you only hear snatches of what’s going on. It matters who is saying what and when, who saw things firsthand, who is repeating what others have said, and who might be just making things up for the sake of a good story. The journals say as much about their writers as they do about their subject. I can glimpse interactions, am never quite certain what is meant by the tone and the timbre, but I have to try to make sense of what there is anyway.

One thing is clear from all these journals and accounts: in those written at the time – the dated diary entries – no-one except Commerson mentions Jeanne at all until after Tahiti. It is only in the retrospective accounts, written or rewritten after their return to France, that anyone mentions any earlier suspicions about Jeanne’s identity. Maybe they always knew, maybe they suspected earlier. But if they did, there is no evidence that anyone said so at the time, not even in their private journals.

It was the ship’s doctor, Vivez, who later claimed that Jeanne’s care for Commerson, including sleeping in his cabin, ‘was not proper’. It’s a slightly strange claim to make. Sleeping alone on a ship would be far more unusual than sleeping in company. The sailors slept side by side in the focsle, separated at best by a few regulation inches. The warrant officers shared cabins, the ship’s boys dossed wherever they could find space. Not even the captain was guaranteed privacy, often sharing the main cabin with his servants, separated only by a canvas curtain. Commerson initially shared his sleeping quarters with the other officers. If he was ill and needed attention, his servant would certainly have slept nearby – this was, in fact, the point of the canvas servants’ berths. Even on land, in the 1700s men habitually shared beds with other men, and women with other women, servants and masters included. Privacy and single rooms were scarce.

I am not convinced that Vivez is an entirely reliable narrator. His narratives are much reworked, and crafted for effect. There are multiple versions. The different versions of his published story, written shortly after his return and then after publication of Bougainville’s account, reveal the way he changed his story, particularly the sections about Jeanne. Like Commerson, Vivez often writes in metaphors and vagaries, but his journals have neither the erratic spontaneity of Commerson’s journals, nor the dry navigational reliability of some of the officers. The historian John Dunmore notes that his descriptions of Jeanne Barret are written in ‘rather bantering and slightly salacious style’. His double-entendres about Jeanne and Commerson’s ‘mutual attachments’ and ‘quiet periods of enjoyment’ rapidly become tiresome, and I’m not sure how much credence I should lend them. And yet I cannot ignore them. Vivez’s journals are the main source of information about Jeanne. However much he gilds the lily, I still suspect that his accounts are based on some kernel of truth.

Many of the challenges for women at sea are obvious. For one thing, washing and toileting on board was very much a public activity. The ship’s head is the ship’s toilet. On sailing ships they were traditionally no more than a platform each side of the bowsprit with slotted panels to allow the waves to wash away the soilage, positioned behind the decorative head timbers that culminated in the figurehead. They offered no privacy and all the crew used them.

Other women who wrote about their life as men at sea in the eighteenth century, like Hannah Snell or Mary Lacy, did not mention any particular problems with toilets or washing. They must have managed somehow. Perhaps discretion all came down to careful timing – or a bucket.

Sometimes the lowest tech solutions are the best. Even internationally famous climate activists have to make do with a bucket on Atlantic crossings. Greta Thunberg made the trip on a zero-carbon yacht, with reporters excitedly describing its solar panels and hydro-turbines, to power the electrics on board. The old-fashioned technology that has driven much human expansion around the world – sail power – was all but forgotten. Old tech, like a bucket, doesn’t often make headlines.

Not all of the challenges to being a woman at sea are as obvious as toilets. Some of them are peculiar and distinctive to the sea itself – unpredictable to anyone unfamiliar with its culture. As they sailed south-west, the weather slowly warmed and steadied until, in late March, the Étoile crossed the equator.

The Baptism of the Line was a rite of passage decreed by gods and kings older than any of those in France. No naval or royal decrees governed these proceedings, no captain dared deny the crew this ceremony, but instead duly relinquished the deck to Neptune or Father Equator for the duration of the proceedings. The social landscape was levelled – no nobleman was too aristocratic, no gentleman too important to escape it, no matter how absurd he might consider the whole escapade. All men stood equal before the sea. To shirk from the ceremony would not only create suspicion in the eyes of the highly superstitious crew, but also cast a shadow on the safety of the ship. It seemed there was no avoiding it.

As soon as Jeanne, along with every other initiate, received a letter demanding her participation, she would have known what was in store. The roll was called to ensure that everyone was present. Father Equator descended from the topmasts with all his acolytes. Initiates could expect to be stripped, dunked and abused in this ceremony. Less favoured crew, even junior officers, might be dumped naked into the water-filled longboat and covered in soot. The foredeck frequently degenerated into a free-for-all until everyone was battered and bruised, soaked and half-drowned.

Every boy on the ship stood naked, covered with a black mix of oil, soot or tar and covered with chicken feathers. The rest of the crew dressed in sheepskin, with devil’s horns, tails and claws. Some of them walked on all fours. Others danced like bears. The boys swung in the rigging like monkeys. All of them were neighing, growling, meowing and barking madly to the accompaniment of twenty goat horns and every pot and pan from the ship’s galley.

This noisy intimidating parade circled the waiting initiates until finally Father Equator, in his triple crown, took his throne and called his demons to silence.

‘Do you promise to do unto others as is done unto you?’

‘Do you swear never to make love to a sailor’s wife?’

As the horned and decorated officials passed along the line, they dispensed their dubious honours. Soon they came to Jeanne. Was this to be her dénouement, her adventure cut short, exposed before she had even reached their first port of call? Perhaps, if Jeanne had still been an impoverished peasant girl, vulnerable to the fickle tempests of superstition and tradition. But she was not. She was a gentleman’s valet now, with privilege and money on her side. And Commerson had already ‘greased the fat pig’, paid off the sailors and ensured a safe passage for them both through this potentially risky and humiliating ceremony.

‘All we had to do was to place our offering in the bowl held by the other assistant,’ he confessed, ‘but we had agreed among ourselves that we would do this only after having been well and duly baptised, as we did not want to refuse the lavabo, and had prepared for this. We had merely come to the private arrangement that we would be spared the bawdy jokes reserved for the sailors, so that we were all well-watered, firstly by the officials of his ceremony, then by ourselves, time and again throwing bucketfuls of water at each other and sparing no-one.’

Commerson dismissed the superstitious event as depressing and barely even worth mentioning in his journal, for all he describes it in detail in a letter home, but Jeanne must have been profoundly grateful that they had been able to buy themselves out of the worst of it by means of a generous offering.

Commerson’s writing often makes me laugh. His impatient enthusiasm, his furious irritation, his effortless superiority is laid bare in his writing. I can see why he must have annoyed some of his colleagues and captivated others. His circumlocutions and omissions drive me to distraction as often as his extravagant claims amuse me.

I order his journal from archives in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle and it duly arrives, a large pale hard-bound volume so old and delicate that I worry that it will fall apart when I open it. If this were an Australian archive I probably would not even be allowed to look at it, certainly not without supervision, substantial cushions, gloves and having first been frisked for illicit pens. But eighteenth-century diaries are not so precious or rare in France. The supervising archivist delivers the manuscripts, returns to her desk and I am left to open the pages by myself.

The front page is grandly inscribed with its author and title in large ornate print. Each of the 380 pages in the book has had a border of four margins ruled in pencil along each side. Each page has been divided in half – four days per spread – enough for a journey of more than four years. The earliest pages are filled with Commerson’s closely spaced handwriting, but the entries gradually reduce to a small paragraph for each day as they settle into the tedium, and sickness, of their first long sea crossing.

I am impressed that he managed to write anything at all during his two weeks of illness. I well recall writing enthusiastically in my own brand-new diary as when we first headed out to sea. My zeal declined as quickly as the swell picked up on passing the headland. I have never been a good diarist even when I was not seasick.

My mother often laughed about my fondness for ‘making books’ as a child. I would carefully decorate the front cover, print out the ornate title, inscribe my own name and write the blurb on the back. I was good at title pages, and the table of contents, numbering the pages and making a start on the introduction, but I almost never got further than that. The only one I finished was a book on ‘Animals’ for a school competition, although I remember the final pages being something of a trial. My mother was firm and encouraging – she was always one for finishing what you start. When I completed the book, she typed, printed and ‘published’ nine copies for my ninth birthday. Neither she nor I could ever have predicted how closely my adult career would follow my childhood interests. Perhaps the Jesuits were right when they claimed that if you gave them a child until the age of seven, they would show you the man. Parental guidance exerts a lasting influence, and every time I think about giving up on a book, even this one, I remember my mother’s rebuke and labour on determinedly until it is finished.

In the library of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, I look at the pile of manuscript boxes I have ordered from the archives. It is unexpectedly hot for early summer and the windows of the library open out into the famous gardens beyond. I would rather be outside than in this stuffy room, struggling with Commerson’s handwriting, checking for passages and annotations that are not included in the transcribed printed versions. On 27 February they sighted land – the Canary Islands – and Commerson enthusiastically drew an outline of the coast. On 13 and 14 March there was a sudden flurry of activity when they caught the sharks and saw the pilot fish. Commerson marks the margin with a manicule: the classic pointing hand reminiscent of Monty Python sketches.

His writing provides a visual map of the ebb and flow of a long sea voyage – the long stretches of tedium punctuated by short periods of intense activity, and sometimes terror. A few days later he included a small pencil sketch of a tuna. His journal was starting to look like a biologist’s. But his enthusiasm soon waned. By the end of March the entries reduced to brief headings, ceasing altogether on the first of April. They were still a month off the South American coast.

The remaining 250 pages of the journal are completely empty.

Historians rarely seem to mention the weather. I suppose weather doesn’t usually have much influence in the archives, beyond the minor discomforts of inadequate heating or airconditioning. Writers too suffer from this pitfall. The weather is a vista outside my office window into which I prefer not to venture unless the conditions are perfect.

But weather is everything and inescapable for sailors. They watch the horizon, check the colour of dawn and dusk, trace the patterns of clouds across the sky, measure the rise and fall of the swell, and observe the behaviour of small creatures above and below the surface. They are anxious and always waiting for the weather, for the change, for the storm, which always comes one way or another. For sailors, the weather is wind. The sea moderates the extremes of temperature. Rain provides fresh water, but it is more important for dampening the wind – helpful in bad weather: devastating in the doldrums and monsoons where flat windless seas leave ships drenched and drifting under relentless rain for weeks on end.

It is the wind that dominates a sailing life. Wind fills the ship’s sails, drives them forward, gives them motion and power. Too little and they drift without direction. The wind beats the ships back onto a lee shore, drives them sideways, rips sails from masts, snaps stays and spars and flings men from rigging. It is the wind that rouses the surface of the ocean into giant fists that pound and crush, that slices icy sheets of water off the surface and whips them stinging across skin and eyes. Nothing else much matters but wind – what direction it comes from and at what speed.

Land dwellers care more about temperature. I remember standing stoic on the back deck of our boat, before we left Port Lincoln, encased in oversized wet-weather gear, a garbage bag of dry clothes scrunched in one hand, my school bag in the other. We watched the white caps rip across the bay, the boats swinging wildly on their moorings, and listened to the wind screaming through rigging.

We waited for a lull, a pause, a space long enough for us to dash to shore, and not be swept out to sea, a moment where oars might row faster and stronger than wind.

‘Now,’ my father said, leaping into the dinghy. We tumbled after him, dropping fast and sitting low, clinging to the sideboard. Casting off, the oars pounded the water in short sharp stabs, giving the wind no purchase on their blades, maintaining our grip on the water beneath. Reddened faces slapped with cold salt spray, gasping breath. One hand for the ship, one hand for yourself. Eyes up, keep alert. There is no hiding from the weather at sea, no time for fear or anxiety. There is just surviving.

The wind rose and we flung ourselves behind a moored fishing boat, clinging in the shelter of its stern until the squall exhausted itself. We cast off and tried again, leapfrogging, boat to boat, until at last we reached the grateful shore.

In town, down the street, people buttoned their coats, pulled down their hats, leapt into their cars, went to work, carried on their business. They barely noticed the weather. Kids hurried through the school gates, shouting and laughing, excited by the wind whipping leaves from the trees, while we shook the salt and adrenaline from our veins. There was no danger here.

Recently I heard a fisherman on the news being interviewed about a cyclone in north Queensland.

‘I’ve been at sea for 45 years,’ he said. ‘Every morning you get up knowing that Mother Nature will try and kill you.’

Bougainville’s journal does not record the temperature, or the humidity, or the time of sunrise and sunset. Sun or snow make little difference. He only recorded the wind and waves. The breeze was fresh, light, good, slight, little, squally, variable, head, calm. The weather was fair, overcast, hazy, stormy, unfavourable. Occasionally, when they were in the tropics, he made a grudging mention of great heat or torrential rain.

I rather suspect the log books of our own voyage would be similar. Pragmatic rather than descriptive. My parents rarely recorded the things that were of most interest to me. I had hoped I might be able to refer to them, but they have been lost over the years, perhaps irretrievably damaged by heat and humidity. But perhaps it is better to rely on the imperfectly personal memories after all. Perhaps it is not necessarily what happened that is so important as how it affects us.

The Étoile was supposed to rendezvous with the Boudeuse at the Falkland Islands, tucked just north-west of the tip of South America, where Bougainville waited in vain through March and April 1767. The Étoile had intended to leave in December 1766, but did not get underway until February of the next year. They arrived off the coast near Rio de Janeiro, but took a further three weeks to sail just halfway – some 2000 kilometres – down the coast towards the Falklands. The Étoile was running short on fresh water and food.

The officers may not, in any case, have been in a hurry to meet up with the expedition commander – not until they had dealt with some of the private supplies they had loaded for their own profit. Such pacquotilles were absolutely forbidden on naval vessels, although in practice a blind eye might be turned to minor goods.

‘To push it to the extent that the provisions are substituted, and food and water compromised for the unhappy crew, to deprive them of the space of the decks and oblige them to sleep here and there on badly stowed chests and bins in danger of being crushed by them, is an abuse,’ declared Commerson. He clearly did not consider the private goods he had brought on behalf of a Rochefort surgeon, to be sold at a profit of 628 livres, to be the same thing.

The Étoile finally sailed into Montevideo for repairs and resupplies on 30 April 1767.

If there had been rumours during the Atlantic crossing, if they had been investigated and substantiated, then Jeanne could have been sent home from South America. Several women were returning home from the colonies. Jeanne could easily have been affixed to one of these families as a servant.

But she was not.

Vivez claimed that at some point before their arrival at Montevideo, Jeanne had been forced to sleep with the other servants after complaints had been made about her sharing Commerson’s cabin. The servants, apparently, believed she was a woman and wanted the matter resolved. According to Vivez, Jeanne told them she was a eunuch and, after a time, for lack of further evidence, interest in the matter died down.

No-one else mentions this particular incident, but Saint-Germain, Bougainville’s naval clerk on the Boudeuse, later claimed to have had his doubts about Jeanne.

‘It had been long suspected that M. de Commerson, a botanist doctor aboard the Étoile, had a girl for a servant, whom he had embarked at Rochefort,’ Saint-Germain later recalled in his account of the journey. ‘At Montevideo, there had been much discussion; which various sailors had wished to visit. But the captain, who, I believe, was not interested in secrecy, caused the most severe prohibitions to be made in this respect.’

Saint-Germain assumed that Commerson did not know Jeanne was a woman when he employed her in Rochefort. ‘But he knew it in Montevideo,’ Saint-Germain notes. ‘They even had fairly conclusive proof of that. Why did they not send her back from Montevideo with the Falkland colonists?’

Perhaps neither Bougainville nor La Giraudais would have wanted to upset their prized naturalist by sending his servant home. Commerson received lucrative offers in South America to travel across the continent and rejoin the ships on the other side. In a land of such obvious biological wealth after a long and nauseating sea voyage, it must have been very tempting.

Saint-Germain does not discuss what the ‘fairly conclusive proof’ in Montevideo was. But Vivez does say that Jeanne fell ill during their stay at Buenos Aires, on the opposite side of the Rio de la Plata from Montevideo. Perhaps with his privileged medical knowledge, Vivez had some evidence.

‘Scandalous gossip claims that she suffered at Buenos Aires from an acute illness brought about by the care she gave her master to relieve him from the weaknesses he might have had during the nights when she watched over him.’

An acute illness, particularly one caused by spending the nights with Commerson, sounds suspiciously like Vivez is hinting at a sexually transmitted disease. Such diseases were rife on eighteenth-century ships and, as the ship’s doctor, Vivez was responsible for treating them, just as he was in charge of treating the wound on Commerson’s leg. But Vivez reports Jeanne’s illness only as ‘scandalous gossip’, not as a known fact, which makes me think she did not seek treatment from him. Other woman have avoided medical treatment so as not to reveal their gender. Hannah Snell said she removed a bullet from her own thigh rather than reveal her identity to the ship’s surgeon. I would not be surprised if Jeanne avoided Vivez’s ministrations. Commerson could have provided her with most medical treatment. Vivez’s claim of a sexually transmitted illness sounds like just another opportunity to make sexual allusions. Accounts of women at sea are so often coloured by implausible accusations of sexual promiscuity that I am immediately sceptical. There is no other evidence that Jeanne was sick in South America, and in fact there is ample evidence that she was healthy enough to be extremely busy indeed.

I am curious about La Giraudais’s ‘severe prohibitions’ though. Perhaps he decided to turn a blind eye to the rumours. It would not be the only time that a captain had chosen not to reveal the identity of a woman on their ship. Marie Louise Victoire Girardin, who sailed on d’Entrecasteaux’s 1791–94 expedition as a male steward, was introduced to the captain Jean-Michel Huon de Kermadec by his sister. It seems likely that both Kermadec and d’Entrecasteaux knew her true identity.

Perhaps La Giraudais simply did not believe that the rumours could be true. Jeanne did not behave like a woman, and what woman would choose to sail aboard a ship anyway? One thing everyone agreed upon was that Jeanne was well behaved and caused no-one any trouble. And once they reached South America, her true value as a collector would be revealed.